Romans in Sudan

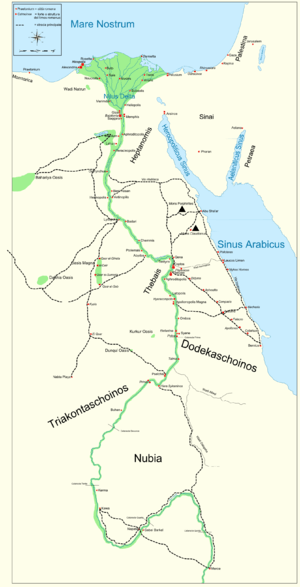

Romans in Sudan is related to the presence of the Roman Empire south of Roman Egypt, in an area usually called "Nubia" by the Romans and now named Sudan.

Historical background

Rome's conquest of Egypt led to border skirmishes and incursions by the kingdom of Meroë (in actual northern Sudan) beyond the Roman borders. In 23 BC the Roman governor of Egypt, Publius Petronius, to end the Meroitic raids, invaded Nubia in response to a Nubian attack on southern Egypt, pillaging the north of the region and sacking Napata (22 BC) before returning home. In retaliation, the Nubians crossed the lower border of Egypt and looted many statues (among other things) from the Egyptian towns near the first cataract of the Nile at Aswan. Roman forces later reclaimed many of the statues intact, and others were returned following the peace treaty signed in 22 BCE between Rome and Meroe. One looted head though, from a statue of the emperor Augustus, was buried under the steps of a temple. It is now kept in the British Museum.[1]

Indeed Petronius led a campaign into present-day central Sudan against the Kingdom of Kush at Meroe, whose queen Imanarenat had previously attacked Roman Egypt. Failing to acquire permanent gains, he razed the city of Napata 22 BC to the ground and retreated to the north.

In 25 BC, the Romans were planning a campaign against both Nubia (Meroe) and Arabia – Augustus bragged about this in his Res Gestae “two armies were led at about the same time into Aethiopia and into the Arabia called Felix".Before the Romans had even tried anything, the Nubians attacked the Thebaid, and the Roman garrison at Syene.They enslaved inhabitants and pulled down Augustus’ statues.The prefect of Egypt, Petronius led 10,000 infantry against 30,000 Nubians, chasing them back to Nubia. He then sacked the seat of the Nubian queen – queen Candace (actually Queen Amanirenas, with title of “candace”) known from Nubian inscriptions. He enslaved the inhabitants (sending 1000 to Augustus presumably for the games) and set up Roman garrison nearby.However, after the change in imperial policy later in Octavian Augustus, the Romans gave up their ambitions to conquer Meroe. They instead treated it as a "client state". Strabo talks about the Nubian ambassadors making a treaty with Augustus.Paul Clammer

Indeed Strabo describes a war with the Romans in the 1st century BC. After the initial victories of Kandake (or "Candace") Amanirenas against Roman Egypt, the Kushites of northern Nubia were defeated and Napata sacked.[2]

Remarkably, the destruction of the capital of Napata was not a crippling blow to the Kushites and did not frighten Candace enough to prevent her from again engaging in combat with the Roman military.

Furthermore, it seems that Gaius Petronius attack might have had a revitalizing influence on the kingdom. Just three years later, in 22 BC, a large Kushite force moved northward with intention of attacking Qasr Ibrim. Alerted to the advance, Petronius again marched south and managed to reach Qasr Ibrim and bolster its defences before the invading Kushites arrived.

Although the ancient sources give no description of the ensuing battle, we know that at some point the Kushites sent ambassadors to negotiate a peace settlement with Petronius and possibly accept a status like "Client State" of Rome.

The next recorded contact between Rome and Meroe was in the autumn of AD 61. The Emperor Nero sent a party of Praetorian soldiers under the command of a tribune and two centurions into this country, who reached the city of Meroe where they were given an escort, then proceeded up the White Nile until they encountered the swamps of the Sudd and possibly reached lake Victoria. This marked the limit of Roman penetration into Africa.[3] It is possible that the Roman emperor Nero planned another attempt to conquer Kush before his death in 68 AD.[4]:150–151

The period following Petronius' punitive expedition and Nero explorations is marked by abundant Roman trade finds at sites in Meroe. L.P. Kirwan provides a short list of finds from archeological sites in that country.[5] However, the kingdom of Meroe began to fade as a power by the 1st or 2nd century AD, sapped by the war with Roman Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.[6] Furthermore, French mineralogist Frédéric Cailliaud (1787–1869), who published an illustrated in-folio describing the ruins of Meroe, had in his work included the first publication of the southernmost known Latin inscription.[7]

At some point during the 4th century, the region of actual Sudan was conquered by the Noba people, from which the name Nubia may derive (another possibility is that it comes from Nub, the Egyptian word for gold[8]). From then on, the Romans referred to the people of the area as the Nobatae.

Around 350 AD, the area was invaded by the Kingdom of Aksum and the kingdom of Meroe collapsed. Eventually, three smaller kingdoms (that become fully "Christian" at the beginning of the fifth century) replaced it: northernmost was Nobatia between the first and second cataract of the Nile River, with its capital at Pachoras (modern-day Faras); in the middle was Makuria, with its capital at Old Dongola; and southernmost was Alodia, with its capital at Soba (near Khartoum). King Silky of Nobatia crushed the Blemmyes, who lived in the territories of actual Sudan between the Nile river and the Red sea.

These Blemmyes raided Roman Egypt since the third century.[9] In 250 AD the Roman Emperor Decius took a lot of effort to win over an invasion army of Blemmyes. A few years later, in 253, they attacked Lower Aegyptus (Thebais) again but were quickly defeated. In 265 they were defeated again by the Roman Prefect Firmus who later in 273 would rebel against the Empire and the Queen of Palmyra Zenobia with the help of the Blemmyes themselves. The Roman general Probus took some time to defeat the usurper and his allies but couldn't prevent the occupation of Thebais by the Blemmyes. That meant another war and the almost entire destruction of the Blemmyes army (279-280). In the reign of Diocletian the province of Lower Aegyptus (Thebais) was again occupied by the Blemmyes. In 298 AD, Diocletian made peace with the Nobatae and Blemmyes tribes, agreeing that Rome move its borders north to Philae (South Egypt, south of Aswan).

Since then there were no more wars/conflicts between Nubia and Roman Egypt, even because of the influence of Christianity,[10] until the arrival of the Arabs.

Legacy of Rome: Christianity

The Roman empire influenced what is now Sudan in many ways, from the economic and commercial to the religious. The most enduring legacy through the centuries seems to be the Christian faith. Indeed Christianity reached the area of present-day northern Sudan, then called Nubia, by about the end of the first century after Christ, then spread to the south of Meroe by the third century. Increased missionary activity from Roman Egypt is recorded for 324 AD in Nubia, according to historian Richard Lobban. It greatly developed under the influence of the Eastern Roman Empire:[11] indeed, Byzantine architecture influenced most of the Christian churches in lower Nubia.[12]

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (reigned 527 to 565 AD) made Nubia a stronghold of Christianity during the Middle Ages.[13] So, by 580 AD Christianity had become the official religion of the northern Sudan, centered around the Faras cathedral.

The Christian faith largely disappeared following Islamic conquests (from the 7th century onwards), but only after a lengthy struggle that went on for eight centuries until 1504 AD (when the Kingdom of Alodia fell). Indeed The Book of Knowledge, a travelogue compiled by a Spanish monk soon after 1348, mentions that Genoese merchants had settled in Old Dongola; they may have penetrated there as a consequence of the commercial treaty of 1290 between Genoa and Egypt.[14] However, during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the Christian town was in decline. It was attacked by Arabs several times, and the throne room of the palace was converted to a mosque.[15]

In the nineteenth century the Mahdist state (1881-1898) forcibly converted most of the remaining Coptic Christians to Islam.[16] But a few Christians survived south of Khartoum in what is now Southern Sudan until our times.[17]

Notes

- ↑ "Bronze head of Augustus". British Museum. 1999. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ↑ Arthur E. Robinson, "The Arab Dynasty of Dar For (Darfur): Part II", Journal of the Royal African Society (Lond). XXVIII: 55-67 (October, 1928)

- ↑ L.P. Kirwan, "Rome beyond The Southern Egyptian Frontier", Geographical Journal, 123 (1957), pp. 16f

- ↑ Jackson, Robert B. (2002). At Empire's Edge: Exploring Rome's Egyptian Frontier. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300088566.

- ↑ Kirwan, "Rome beyond", pp. 18f

- ↑ ""Nubia", ''BBC World Service''". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ CIL III, 83. This inscription was subsequently published by Lepsius, who brought the stone back to Berlin. Although thought lost, it was recently rediscovered in the Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin; see Adam Łajtar and Jacques van der Vliet, "Rome-Meroe-Berlin. The Southernmost Latin Inscription Rediscovered ('CIL' III 83)", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 157 (2006), pp. 193-198

- ↑ "Nubia". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ History of Blemmyes and nomads in southern Egypt and Nubia, Saudi Aramco World, May/June 1998.

- ↑ Relationship between Egypt and the Christian kingdoms of Nubia p. 11-19

- ↑ "Christianity in Nubia". Nubianet.org. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ Photos of Christian Nubia churches. Books.google.com. 2010-08-11. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "Christian Nubia and the Eastern Roman Empire". Rumkatkilise.org. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ O.G.S. Crawford, "Some Medieval Theories about the Nile", Geographical Journal, 114 (1949), pp. 7f

- ↑ P. L. and M. Shinnie, "New Light on Medieval Nubia", Journal of African History, 6 (1965), p. 265

- ↑ Sheen J. Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. Routledge, 1997. p.75.

- ↑ Christian "Fazughli" kingdom in southern Sudan

Bibliography

- Leclant, Jean (2004). The empire of Kush: Napata and Meroe. London: UNESCO. pp. 1912 Pages. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- Roger S. Bagnall. Publius Petronius, Augustan Prefect of Egypt. In: Naphtali Lewis (Hrsg.): Papyrology (Yale Classical Studies XXVIII) (1985). S. 85–93.

- Richard Lobban, Coptic Egypt influence on Christian kingdoms of Sudan Paper presented at the "Conference on Egypt and the Biblical Countries" at the Russian State University, 11–14 October 2004, Moscow, Russia.

See also

- Roman Egypt

- Nero expedition to Nile sources

- Romans in Arabia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||