Romanization (cultural)

- Romanization may also refer to linguistics see Romanization (disambiguation).

Romanization or Latinization (or Romanisation or Latinisation: see spelling differences)—in the historical and cultural meanings of both terms—indicate different historical processes, such as acculturation, integration and assimilation of newly incorporated and peripheral populations by the Roman Republic and the later Roman Empire. Ancient Roman historiography and Italian historiography until the fascist period used to call these various processes the "civilizing of barbarians".

Characteristics

The acculturation proceeded from the top down, the upper classes adopting Roman culture first and the old ways lingering longest in outlying districts among peasants.[1] Hostages played an important part in this process, as elite children, from Mauretania to Gaul, were taken to be raised and educated in Rome.[2]

Ancient Roman historiography and traditional Italian historiography confidently identified the different processes involved with a "civilization of barbarians". Modern historians take a more nuanced view: by making their peace with Rome, local elites could make their position more secure and reinforce their prestige. New themes include the study of personal and group values and the construction of identity, the personal aspect of ethnogenesis. These transitions operated differently in different provinces; as Blagg and Millett point out[3] even a Roman province may be too broad a canvas for generalizations.

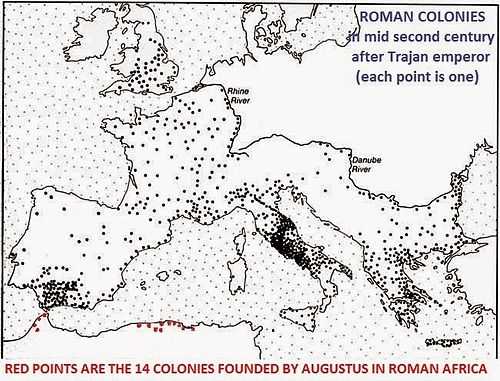

One characteristic of cultural Romanization was the creation of many hundreds of Roman coloniae in the territory of the Roman Republic and the subsequent Roman Empire. Until Trajan, colonies were created using veterans, mainly from the Italian peninsula, who promoted Roman customs and laws, with the use of Latin.

About 400 towns (of the Roman Empire) are known to have possessed the rank of colonia. During the empire, colonies were showcases of Roman culture and examples of the Roman way of life. The native population of the provinces could see how they were expected to live. Because of this function, the promotion of a town to the status of "Colonia civium Romanorum" implied that all citizens received full citizen rights and dedicated a temple to the Capitoline triad: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, the deities venerated in the temple of Jupiter Best and Biggest on the Capitol in Rome. Livius [4]

Process of Romanization

The very existence is a source of contention among modern archaeologists.[5] One of the first approaches, which can be regarded as the "traditional" approach today, was taken by Francis Haverfield.[6] He saw this process beginning in primarily post-conquest societies (e.g. Britain and Gaul) where direct Roman policy from the top promoted an increase in the 'Roman' population of the province through the establishment of veteran colonies. These coloniae would have spoken Latin and have been citizens of Rome following their army tenure (See Roman citizenship) – Haverfield thus assumes this would have a 'Romanising' effect upon the native communities.

This thought process, fueled though it was by early 20th century standards of Imperialism and cultural change, forms the basis for the modern understanding of Romanization. However, recent scholarship has devoted itself to providing alternate models of how native populations adopted Roman culture, while questioning the extent to which it was accepted or resisted.

- Non-Interventionist Model[7] – Native elites were encouraged to increase social standing through association with the powerful conqueror be it in dress, language, housing and food consumption. This provides them with associated power. The establishment of a civil administration system is quickly imposed to solidify the permanence of Roman rule.

- Discrepant Identity[8] – No uniformity of identity which we can accurately describe as traditional 'Romanization'. Fundamental differences within a province are visible through economics, religion and identity. Not all provincials were pro-Rome, nor did all elites seek to be like the Roman upper classes.

- Acculturation[9] – Aspects of both Native and Roman cultures are joined together. This can be seen in the Roman acceptance, and adoption of, non-Classical religious practices. The inclusion of Isis, Epona, Britannia and Dolychenus into the pantheon are evidence of this.

- Creolization[10] – Romanization occurs as a result of negotiation between different elements of non-egalitarian societies. Material culture is therefore ambiguous.

Romanization is not a clear-cut process of cultural adoption. The paradigm is over-used and confused; different definitions prevent any useful application of the concept. The major criticism of this idea is that it is reliant upon the arbitrary allocation of labels such as Roman and Native to various cultural and material elements with little or no firm reasoning to do so. As it cannot be used to explain, Romanization should only be used as a theoretical tool with which to approach the Roman Provinces and not as an archaeologically verifiable process.

Results of Romanization

all this slowly culminated in many gradual developments:

- adoption of Roman names.

- gradual adoption of the Latin language. This process was greatly facilitated by the simple fact that many cultures were mostly oral (particularly the Gauls and Iberians), and anyone who wanted to deal (through writing) with the bureaucracy and/or with the Roman market needed to write in Latin. The extent of this adoption is subject to ongoing debate, as the native languages were certainly spoken after any conquest. Moreover, in the eastern half of the Empire, Latin had to compete with Greek which largely kept its position as lingua franca and even spread to new areas. Latin became prominent in certain areas around new veteran colonies like Berytus.

- replacement of the ancient tribal laws by Roman law, with its institutions of property rights.

- the dissemination of typically Roman institutions such as public baths, the Emperor cult and gladiator fights.

In due time, the conquered would see themselves as Romans.

This process was supported by the Roman Republic and by its successor the Roman Empire.

The entire process was facilitated by the fact that many of the local languages had the same Indo-European origin and by the similarity of the gods of many ancient cultures. They also already had had trade relations and contacts with each other through the seafaring Mediterranean cultures like the Phoenicians and the Greeks.

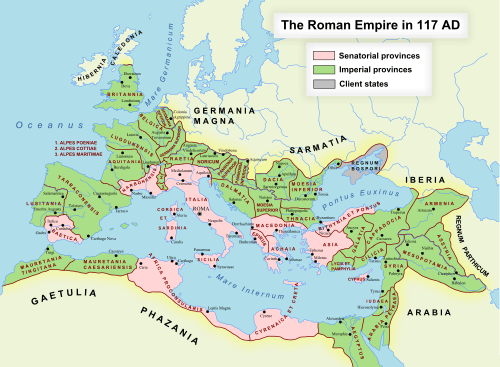

Romanization was largely effective in the western half of the Empire, where native civilizations were weaker. In the Hellenized East, ancient civilizations like those of Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Judea and Syria, effectively resisted all but its most superficial effects. When the Empire was divided into two, in the east where Greek culture was centered, the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire was marked by the increasing strength of specifically Greek culture and language to the detriment of the Latin language and other romanizing influences, even though its citizens continued to regard themselves as Romans.

While Britain certainly was Romanized , its approximation to the Roman culture seems to have been smaller than that of Gaul, for example, and the Roman culture quickly collapsed after the Anglo-Saxon invasion. The most romanized regions of the Empire were Italy, the Iberian Peninsula, Gaul and Dalmatia.

Romanization in most of these regions remains such a powerful cultural influence in most aspects of life today that they are described as "Latin countries". This is most evident in those European countries in which Latin derived languages are spoken and former colonies that have inherited these languages and other Roman influences. According to Theodore Mommsen the cultural romanisation was more complete in those areas that developed a "neolatin language" (like Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese): a process that later developed in their own colonial empires in the recent centuries.

See also

- Latinization of names

- Roman citizenship

- Latin Right

- Latin Europe

- Romanization of Hispania

- Thraco-Roman

- Gallo-Roman

- Daco-Roman

- Romano-British culture

Notes

- ↑ The identification of countryfolk as pagani is discussed at paganism.

- ↑ Leonard A. Curchin, The Romanization of Central Spain: complexity, diversity, and change in a Provincial Hintellrfreshsrland, 2004, p. 130.

- ↑ T. F. C. Blagg and M. Millett, eds., The Early Roman Empire in the West 1999, p. 43.

- ↑ Coloniae

- ↑ Mattingly, D. J., 2004, "Being Roman: Expressing Identity in a provincial setting", Journal of Roman Archaeology Vol. 17, pp 5–26

- ↑ Haverfield, F., 1912, The Romanization of Roman Britain, Oxford: Claredon Press

- ↑ Millet, M., 1990, "Romanization: historical issues and archaeological interpretation", in Blagg, T. and Millett, M. (Eds.), The Early Roman Empire in the West, Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 35–44

- ↑ Mattingly, D. J., 2004, "Being Roman: Expressing Identity in a provincial setting", Journal of Roman Archaeology Vol. 17, pp. 13

- ↑ Webster, J., 1997 "Necessary Comparisons: A Post-Colonial Approach to Religious Syncretism in the Roman Provinces", World Archaeology Vol 28 No 3, pp. 324–338

- ↑ Webster, J., 2001, "Creolizing the Roman Provinces", American Journal of Archaeology Vol 105 No. 2, pp. 209–225,

References

- Adrian Goldsworthy. The Complete Roman Army. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05124-0.

- Francisco Marco Simón, "Religion and Religious Practices of the Ancient Celts of the Iberian Peninsula" in e-Keltoi: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula, 6 287–345 (online) Interpretatio and the Romanization of Celtic deities.

- Mommsen, Theodore. The Provinces of the Roman Empire Barnes & Noble (re-edition). New York, 2004

- Susanne Pilhofer: "Romanisierung in Kilikien? Das Zeugnis der Inschriften" (Quellen und Forschungen zur Antiken Welt 46), Munich 2006.

External links

| ||||||||||||||