Roman de Fauvel

The Roman de Fauvel is a 14th-century French allegorical verse romance of satirical bent, generally attributed to Gervais de Bus, a clerk at the French royal chancery. The original narrative of 3,280 octosyllabics is divided into two books, dated to 1310 and 1314 respectively. In 1316–7 Chaillou de Pesstain produced a greatly expanded version.

The romance features Fauvel, a fallow-colored horse who rises to prominence in the French royal court, and through him satirizes the self-serving hedonism and hypocrisy of men, and the excesses of the ruling estates, both secular and ecclesiastical. The antihero's name can be broken down to mean "false veil", and also forms an acrostic F-A-V-V-E-L with the letters standing for the human vices: Flattery, Avarice, Vileness, Variability (Fickleness), Envy, and Laxity. The romance also gave birth to the English expression "curry fauvel", the obsolete original form of "curry favor". The work is reminiscent of a similar tract in the 13th-century Roman de la Rose, though owes more to the animal fabliaux of Reynard the Fox.

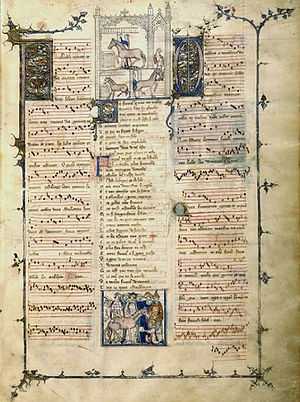

Chaillou's own handwritten manuscript (Paris, BN fr. 146) is splendid work of illuminated art, as well as being of considerable musicological interest due to interpolations of 169 period pieces of music, which span the gamut of thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century genres and textures. Some of these pieces are linked to Philippe de Vitry and the nascent musical style referred to as Ars Nova.

Plot

The poem revolves around the central figure, an ambitious and foolish horse (or ass), called Fauvel. The horse's name itself is rife with symbolism. "Fauvel" comes from the color of its coat, which is "muddy beige"[1] (or fallow-colored.[2][lower-alpha 1]) and symbolic of Vanity.[1] The name breaks down to fau-vel, or "false veil",[5] and is furthermore an acronym F-A-V-V-E-L taken from the head letters of these vices: Flattery, Avarice, Vileness, Variability (Fickleness), Envy, and Laxity (Flaterie, Avarice, Vilanie, Varieté, Envie, Lascheté).[4][6][7]

The first book is a rebuke against the clergy and society, tainted by Sin and corruption. Fauvel though he is a horse no longer resides in a stable, but is set up in a grand house (the royal palace in fact[8]) by the grace of Dame Fortune, the goddess of Fate. He changes his residence to suit his needs, and has a custom manger and hayrack built. In his garderobe (toilet) he has those from the religious order stroking him to make sure "no dung can remain on him."[9] Church and secular leaders far and wide make pilgrimages to see him, and bow to him in servitude. These potentates condescend to brush and clean Fauvel from his tonsured head to tail.[1][10] These fawning groomers are said to "curry" (Old French: torcher) Fauvel in the original phrasing of the work, and this is where the English expression "curry favor" has originated, corrupted from the earlier form "curry fauvel."[11]

Fauvel travels to Macrocosmos and asks Dame Fortune's for her hand in marriage. She denies him, but in her stead she proposes he wed Lady Vainglory. Fauvel agrees, and the wedding takes place, with such guests present as Flirtation, Adultery, Carnal Lust, and Venus, in a technique similar to that of the Morality plays of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Finally, Dame Fortune reveals that Fauvel's role in the world is to give birth to more iniquitous rulers like himself, and to be a harbringer of the Antichrist.

Text

The Roman de Fauvel is a poem of 3280 octasyllabic rhyming couplets,[4] divided into two books: Book 1 in 1226 verses, completed 1310 according to its last verse; and Book 2, in 2054 verses, completed 2014 according to its explicit.[3][12] In 1316–7 Chaillou de Pesstain augmented this text with additional 3000 verses spanning both books (1800 lines of which are spent on Fauvel's wedding).[4][13][14]

Surviving copies

The manuscript survives that contains Chaillou's expanded version in his own hand (Paris, BN fr. 146), and this is the earliest copy of Fauvel to survive. The dozen or so other extant manuscripts are of the non-interpolated form, and these continued to be copied into the fifteenth century.[4][14][15][lower-alpha 2] Chaillou's deluxe manuscript is illustrated with 78 miniatures, and inserts 169 musical pieces, woven into a complex mise-en-page.

Music

Of all the surviving manuscript versions of Le Roman de Fauvel, the copy compiled by Chaillou de Pesstain (BN fr. 146), has attracted the most musicological attention due to the interpolated musical pieces in musical notation, which span the gamut of thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century genres and textures. The 169 pieces all have lyrics, 124 in Latin, 45 in French.[17][lower-alpha 3] The genres cover the liturgical and devotional, sacred and profane, monophonic and polyphonic, chant, old and new music. Some of these pieces are thought to have been composed by Philippe de Vitry. While these pieces were once thought of as arbitrarily selected repertory for textual "accompaniment",[18][19][20] recent scholarship (such as "Fauvel Studies" and Dillon's "Music-Making"[21]) has tended to focus on the ingenious intertextual/glossing role(s) played by musical notation – both visual and aural – in augmenting and diversifying the (political) themes of Gervais' admonitio.[22] Amongst other curious discoveries are the inclusion of numerous "false" chants (Rankin) interspersed between actual liturgical material, perhaps a direct musical play on the deceptive qualities of its equine trickster. Much attention has also been paid to fr. 146's numerous polyphonic motets, some of which (In Nova Fert, for example) exhibit red notation of newer mensural notational innovations generally described under the umbrella of ars nova.

Although the text of the Roman de Fauvel is not particularly well known, the music has been frequently performed and recorded. The question of how the entire work would have been read or staged in the 14th century is the subject of academic debate. Some have suggested that BN fr. 146 could have been intended as a theatrical performance.[22] This hypothesis is of course in contradiction with the concurrent opinion that the Roman de Fauvel is mainly an anthology.[20]

Discography

The first recording of the work has been made in 1972 by the Studio der Frühen Musik (Studio of Early Music) on the EMI Reflexe – label, directed by Thomas Binkley. This recording is currently available as part of a 5-CD box-set on the Virgin-label. The speaker of the verses uses the original old-French, including some now very odd-sounding pronouncing of -still familiar- French words. The musical interludes have some, especially for that time, poignant dissonances/counterpoint; which likely serve to illustrate the mocking nature of the whole Roman.

See also

- Ars nova

- Medieval music#France: Ars nova

- Guillaume de Machaut

- Philippe de Vitry

- Allegory in the Middle Ages

Explanatory notes

- ↑ The corresponding modern French fauve denotes a darker shade of brown, and the color has also been described by other commentators as "fawn"[3] or "dun".[4]

- ↑ "dozen or so" — Långfors's edition counted 11 mss. of the shorter version, which other commentators have followed (Rosenberg & Tischler 1991, Regalado 1995a). But there is one fragment Långfors did not include in his tally, and in 1994 Mühlethaler published the existence of two previously unnoticed manuscript sources (1 complete copy and 1 fragment).[15][16]

- ↑ Or 106 in Latin, 60 in French, and 3 bilingual.[13]

References

- Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Dillon (2002), p. 15.

- ↑ "favel". Oxford English Dictionary 4 (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. 1933. p. 107.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rosenberg & Tischler (1991), p. 1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Regalado (1995a).

- ↑ Dillon (2002), pp. 14, 117.

- ↑ Morrison, Elizabeth; Hedeman, Anne D. (2010). Imagining the Past in France: History in Manuscript Painting, 1250-1500. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. pp. 135–7. ISBN 9781606060285.

- ↑ Dillon (2002), p. 14.

- ↑ Rosenberg & Tischler (1991), p. 5.

- ↑ Roden, Timothy; Wright, Craig; Simms, Bryan (2009). "26. Gervès de Bus, Roman de Fauvel (c. 1314)". Anthology for Music in Western Civilization 1 (New York: Simms). pp. 78–80. ISBN 0-4955-7274-8. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Långfors (1914), p. 8, v. 122:teste le rooignent, tonsured head.

- ↑ "curry favel, curry-favor". Oxford English Dictionary 2 (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. 1933. p. 1272.

- ↑ Dillon (2002), pp. 13, 87.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Regalado (1995b), p. 153.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rosenberg & Tischler (1991), p. 2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dillon (2002), p. 13.

- ↑ Mühlethaler (1994).

- ↑ Regalado (2007), p. 236.

- ↑ Paris (1898), p. 137.

- ↑ Långfors (1914).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gagnepain (1996).

- ↑ Dillon (2002).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Herbelot (1998).

- Bibliography

- du Bus, Gervais; de Pesstain, Chaillou (1914) [1310 & 1314]. Långfors, Arthur, ed. Le Roman de Fauvel [The Romance of Fauvel]. Publications de la Société des anciens textes français (in French). Paris, France: Didot. ISBN 9782253082583. OCLC 621768159. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- Dillon, Emma (2002). Medieval Music-Making and the "Roman de Fauvel". New perspectives in music history and criticism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521813716. OCLC 638807104.

- Gagnepain, Bernard (1996). Histoire de la musique : XIIIe-XIVe siècle [History of Music: thirteenth-fourteenth century]. Solfèges (in French). Paris, France: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 9782020181655. OCLC 807642929, 34797011 and 35658180.

- Herbelot, Aurélie (1998). Le Roman de Fauvel de Chaillou de Pesstain [The Romance of Fauvel by Chaillou of Pesstain] (Master Thesis) (in French). Universite de Savoie. Retrieved 2014-10-11. Google translation of Le Roman de Fauvel de Chaillou de Pesstain

- Mühlethaler, Jean-Claude (1994). Fauvel au pouvoir. Lire la satire médiévale [Fauvel in power: Read the medieval satire]. Nouvelle bibliothèque du Moyen Âge (in French). Paris, France: H. Champion. ISBN 9782852033214. OCLC 781099516.

- Paris, Gaston (1898). "Le Roman de Fauvel". Histoire littéraire de la France 32 (Paris: Imprimere Nationale). pp. 108–153, 597. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Regalado, Nancy F. (1995a). "Fauvel, livre de". In Kibler, William W. Medieval France: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland). pp. 649–650. ISBN 0-8240-4444-4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Regalado, Nancy Freeman (1995b). "The Songs of Jehannot de Lescurel in Paris, BnF, MS fr. 146. Love Lyrics, Moral Wisdom and the Material Book". In Dixon, Rebecca; Sinclair, Finn E. Poetry, Knowledge and Community in Late Medieval France (New York: Garland). pp. 151–172. ISBN 0-8240-4444-4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Regalado, Nancy Freeman (2007). "Swinherds at Court: Kalila et Dimna, Le Roman de Fauvel". In Fresco, Karen Louise; Pfeffer, Wendy. Chancon Legiere a Chanter (Summa Publications, Inc.). pp. 235–254. ISBN 1-8834-7954-1. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Rosenberg, Samuel N.; Tischler, Hans, eds. (1991). The Monophonic songs in the Roman de Fauvel. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803238985.

External links

- "Gervès du Bus - Bibliographie". arlima.net (in French). Les Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (ARLIMA). Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- "Français 146". gallica.bnf.fr. Paris, France: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 2014-10-12. A facsimile of the Français 146 manuscript of Roman de Fauvel. There is also a link to download a PDF of the facsimile.

- "Source Description for Français 146". diamm.ac.uk. Oxford, UK: Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music. Retrieved 2014-10-12. Includes a detailed description, large bibliography, and table of contents for the Français 146 manuscript of Roman de Fauvel.