Roman Catholicism in Croatia

Roman Catholicism in Croatia is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome.

There are an estimated 3.8 million baptised Roman Catholics in Croatia, roughly 85% of the population. The national sanctuary of Croatia is in Marija Bistrica. The patron of Croatia is Saint Joseph since the Croatian Parliament declared him to be in 1687.[1]

Statistics

The published data from the 2011 Croatian census included a crosstab of ethnicity and religion which showed that a total of 3,697,143 Catholic believers (86.28% of the total population) was divided between the following ethnic groups:[2]

- 3,599,038 Catholic Croats

- 22,331 Catholic believers of regional affiliation

- 15,083 Catholic Italians

- 9,396 Catholic Hungarians

- 8,521 Catholic Czechs

- 8,299 Catholic Roma

- 8,081 Catholic Slovenes

- 7,109 Catholic Albanians

- 3,159 Catholic Slovaks

- 2,776 Catholic believers of undeclared nationality

- 2,391 Catholic Serbs

- 1,913 Catholic believers of other nationalities

- 1,847 Catholic Germans

- 1,692 Catholic Ruthenians

- 1,384 Catholic believers of unknown nationality

- 1,339 Catholic Ukrainians

- other individual ethnicities (under 1,000 people each)

History

The Church in the Austrian/Austro-Hungarian Empire

The Austrian Empire signed a concordat with the Holy See in 1855 which regulated the Catholic Church within the empire.[3]

The Church in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

In Yugoslavia, the Croatian bishops were part of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia.

The Serbian Orthodox Church acted as a de facto national church of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. During this period, a Serbian Orthodox church was built on the almost entirely Catholic island of Vis and a part of the local population began converting.[4]

The Church in the Independent State of Croatia

In 1941, the Independent State of Croatia was established by the Ustaša puppet regime with Ante Pavelić as its leader. The Independent State of Croatia was one of several Nazi puppet states. The Ustaša regime pursued a genocidal policy against the Serbs (who were Eastern Orthodox Christians), Jews and Romani.

The creation of the Independent State of Croatia was initially welcomed by many within the Roman Catholic Church. However, one notable figure of the Croatian Catholic Church, Bishop Aloysius Stepinac, made public statements criticising developments in the ISC. On Sunday May 24, 1942 to the irritation of Ustaša officials, he used the pulpit and a diocesan letter to condemn genocide in specific terms:

All men and all races are children of God; all without distinction. Those who are Gypsies, Black, European, or Aryan all have the same rights.... for this reason, the Catholic Church had always condemned, and continues to condemn, all injustice and all violence committed in the name of theories of class, race, or nationality. It is not permissible to persecute Gypsies or Jews because they are thought to be an inferior race.[5]

He also wrote directly to Pavelić, saying on February 24, 1943:

The very Jasenovac camp is a stain on the honor of the ISC. Poglavnik! To those who look at me as a priest and a bishop I say as Christ did on the cross: Father forgive them for they know not what they do.[6]

In December 1941, Chetniks killed a group of five nuns near Goražde. Communist Yugoslav Partisans killed priests Petar Perica and Marijan Blažić on the island of Daksa on October 25, 1944. The Partisans killed fra Maksimilijan Jurčić near Vrgorac in late January 1945.[7]

The Church in communist Yugoslavia

The National Anti-Fascist Council of the People's Liberation of Croatia (ZAVNOH) originally foresaw a greater degree of religious freedom in the country. In 1944 ZAVNOH still left open the possibility of religious education in schools.[8] This idea was scuttled after Yugoslav leader Josip Broz removed secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia Andrija Hebrang and replaced him with hardliner Vladimir Bakarić.[9]

In 1945, the retired bishop of Dubrovnik, Josip Marija Carević, was murdered by Yugoslav authorities.[10] Bishop Josip Srebrnić was sent to jail for two months.[11] After the war, the number of Catholic publications in Yugoslavia decreased from one hundred to only three.[12]

In 1946, the communist regime introduced the Law on State Registry Books which allowed the confiscation of church registries and other documents.[13] On January 31, 1952, the communist regime officially banned all religious education in public schools.[14] That year the regime also expelled the Catholic Faculty of Theology from the University of Zagreb, to which it was not restored until democratic changes in 1991.[15][16]

In 1984, the Catholic Church held a National Eucharistic Congress in Marija Bistrica.[17] The central mass held on September 9 was attended by 400,000 people, including 1100 priests, 35 bishops and archbishops, as well as five cardinals. The mass was led by cardinal Franz König, a friend of Aloysius Stepinac from their early studies. In 1987 the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia issued a statement calling on the government to respect the right of parents to obtain a religious education for their children.[18]

The Church in the Republic of Croatia

With Croatian democratization and independence, the Croatian Bishops' Conference was formed. The Croatian Bishops' Conference established Croatian Catholic Radio in 1997.[19]

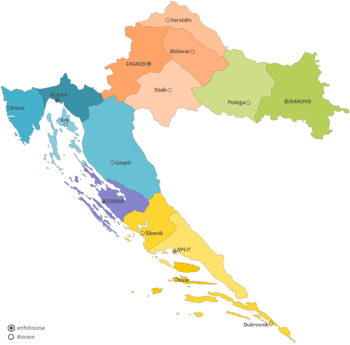

Hierarchy

Within Croatia the hierarchy consists of:

| Archdioceses and dioceses | Croatian name | (Arch-)Bishop | Est. | Cathedral | Weblink |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archdiocese of Zagreb | Zagrebačka nadbiskupija Archidioecesis Zagrebiensis |

Cardinal Josip Bozanić | 1093 | Zagreb Cathedral | |

| Eparchy of Križevci (Greek-Catholic) | Križevačka biskupija | Nikola Kekić | 1777 | Križevci Cathedral Zagreb Co-cathedral |

|

| Diocese of Varaždin | Varaždinska biskupija | Josip Mrzljak | 1997 | Varaždin Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Sisak | Sisačka biskupija | Vlado Košić | 2009 | Sisak Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Bjelovar-Križevci | Bjelovarsko-križevačka biskupija | Vjekoslav Huzjak | 2009 | Bjelovar Cathedral Križevci Co-cathedral |

|

| Archdiocese of Đakovo-Osijek | Đakovačko-osiječka nadbiskupija | Marin Srakić | 4th century | Đakovo Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Požega | Požeška biskupija Dioecesis Poseganus |

Antun Škvorčević | 1997 | Požega Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Srijem (in Serbia) | Srijemska biskupija | Djuro Gašparović | 2008 | ||

| Archdiocese of Rijeka | Riječka nadbiskupija | Ivan Devčić | 1920 | Rijeka Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Gospić-Senj | Gospićko-senjska biskupija | Mile Bogović | 2000 | Gospić Cathedral Senj Co-cathedral |

|

| Diocese of Krk | Krčka biskupija | Valter Župan | 900 | Krk Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Poreč-Pula | Porečko-pulska biskupija | Dražen Kutleša | 3rd century | Euphrasian Basilica Pula Cathedral |

|

| Archdiocese of Split-Makarska | Splitsko-makarska nadbiskupija | Marin Barišić | 3rd century | Split Cathedral Split Co-cathedral |

|

| Diocese of Dubrovnik | Dubrovačka biskupija | Mate Uzinić | 990 | Dubrovnik Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Hvar | Hvarska biskupija | Slobodan Štambuk | 12th century | Hvar Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Kotor (in Montenegro) | Kotorska biskupija | Ilija Janjić | 10th century | Kotor Cathedral | |

| Diocese of Šibenik | Šibenska biskupija | Ante Ivas | 1298 | Šibenik Cathedral | |

| Archdiocese of Zadar | Zadarska nadbiskupija | Želimir Puljić | 1054 | Zadar Cathedral | |

| Military Ordinariate | Vojni ordinarijat | Juraj Jezerinac | 1997 |

The bishops are organized into the Croatian Conference of Bishops, which is presided by the Archbishop of Zadar Mons. Želimir Puljić.

There are also historical bishoprics, including:

Franciscans

There are three Franciscan provinces in the country:

- the Franciscan Province of Saints Cyril and Methodius based in Zagreb,

- the Franciscan Province of Saint Jerome based in Zadar and

- the Franciscan Province of the Most Holy Redeemer based in Split.

Other orders

- Croatian Dominican Province

- Croatian Province of the Society of Jesus

- Croatian Salesian Province of Saint Don Bosco

- Croatian Carmelite Province of Saint Joseph the Father

Places of Pilgrimage of the Croats

- Aljmaš

- Ludbreg

- Our Lady of Marija Bistrica

- Our Lady of Sinj

- Our Lady of Trsat

Notable people

- Franjo Šeper

- Alojzije Stepinac

- Josip Juraj Strossmayer

- Juraj Dobrila

- Franjo Kuharić (Cardinal before Josip Bozanić)

- Ivan Merz, blessed layman and Catholic activist

- Antun Mahnić, initiator of the Croatian Catholic Movement

References

- ↑ Relief of Saint Joseph placed in Parliament

- ↑ "4. Population by ethnicity and religion". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ Ljiljana Dobrovšak. Ženidbeno (bračno) pravo u 19. stoljeću u Hrvatskoj

- ↑ History of the island of Vis

- ↑ Apud: Dr. H. Jansen, Pius XII: chronologie van een onophoudelijk protest, 2003, p. 151

- ↑ Alojzije Viktor Stepinac: 1896-1960

- ↑ Partizan Jure Galić: Moji suborci pobili su 30 Vrgorčana, Slobodna Dalmacija

- ↑ Tanner (1997), p. 164

- ↑ Tanner (1997), p. 165

- ↑ Religious Communities in Croatia from 1945 to 1991

- ↑ Akmadža, Miroslav. Katolička crkva u Hrvatskoj i komunistički režim 1945 - 1966.. Rijeka: Otokar Keršovani, 2004. (pg. 69)

- ↑ Mitja Velikonja. Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press, 2003. (p. 200)

- ↑ Miroslav Akmadža. Oduzimanje crkvenih matičnih knjiga u Hrvatskoj u vrijeme komunizma

- ↑ Akmadža, Miroslav. Katolička crkva u Hrvatskoj i komunistički režim 1945-1966.. Biblioteka Svjedočansta. Rijeka, 2004. (pg. 93)

- ↑ Goldstein, Ivo. Croatia: A History . McGill Queen's University Press, 1999. (pg. 169)

- ↑ Catholic Faculty of Theology History

- ↑ How Gospa destroyed the SFRY, Globus

- ↑ Sabrina P. Ramet. Catholicism and politics in communist societies. Duke University Press, 1990. (p. 194)

- ↑ Hrvatski katolički radio u povodu 10. obljetnice emitiranja, Glas Koncila

- Tanner, Marcus (1997). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07668-1.

External links

| ||||||||||||||

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman Catholicism in Croatia. |