Rolling

Rolling is a type of motion that combines rotation (commonly, of an axially symmetric object) and translation of that object with respect to a surface (either one or the other moves), such that, if ideal conditions exist, the two are in contact with each other without sliding.

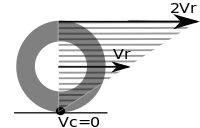

No sliding takes place if and only if the instantaneous velocity of the rolling object in the point(s) in which it contacts the surface is the same as that of the surface; this is referred to as pure rolling. In particular, for a reference plane in which the rolling surface is at rest, the instantaneous velocity of the point of contact of the rolling object is zero.

In practice, due to small deformations near the contact area, some sliding and energy dissipation occurs. Nevertheless, the resulting rolling resistance is much lower than sliding friction, and thus, rolling objects, typically require much less energy to be moved than sliding ones. As a result, such objects will more easily move, if they experience a force with a component along the surface, for instance gravity on a tilted surface, wind, pushing, pulling, or torque from an engine. Unlike most axially symmetrical objects, the rolling motion of a cone is such that while rolling on a flat surface, its center of gravity performs a circular motion, rather than linear motion. Rolling objects are not necessarily axially-symmetrical. Two well known non-axially-symmetrical rollers are the Reuleaux triangle and the Meissner bodies. Objects with corners, such as dice, roll by successive rotations about the edge or corner which is in contact with the surface.

Applications

Most land vehicles use wheels and therefore rolling for displacement. Slip should be kept to a minimum (approximating pure rolling), otherwise loss of control and an accident may result. This may happen when the road is covered in snow, sand, or oil, when taking a turn at high speed or attempting to brake or accelerate suddenly.

One of the most practical applications of rolling objects is the use of rolling-element bearings, such as ball bearings, in rotating devices. Made of metal, the rolling elements are usually encased between two rings that can rotate independently of each other. In most mechanisms, the inner ring is attached to a stationary shaft (or axle). Thus, while the inner ring is stationary, the outer ring is free to move with very little friction. This is the basis for which almost all motors (such as those found in ceiling fans, cars, drills, etc.) rely on to operate. The amount of friction on the mechanism's parts depends on the quality of the ball bearings and how much lubrication is in the mechanism.

Rolling objects are also frequently used as tools for transportation. One of the most basic ways is by placing a (usually flat) object on a series of lined-up rollers, or wheels. The object on the wheels can be moved along them in a straight line, as long as the wheels are continuously replaced in the front (see history of bearings). This method of primitive transportation is efficient when no other machinery is available. Today, the most practical application of objects on wheels are cars, trains, and other human transportation vehicles.

Physics of simple rolling

The simplest case of rolling is that of an axially symmetrical object rolling without slip along a flat surface with its axis parallel to the surface (or equivalently: perpendicular to the surface normal).

The trajectory of any point is a trochoid; in particular, the trajectory of any point in the object axis is a line, while the trajectory of any point in the object rim is a cycloid.

The velocity of any point in the rolling object is given by  , where

, where  is the displacement between the particle and the rolling object's contact point (or line) with the surface, and

is the displacement between the particle and the rolling object's contact point (or line) with the surface, and  is the angular velocity vector. Thus, despite that rolling is different from rotation around a fixed axis, the instantaneous velocity of all particles of the rolling object is the same as if it was rotating around an axis that passes through the point of contact with the same angular velocity.

is the angular velocity vector. Thus, despite that rolling is different from rotation around a fixed axis, the instantaneous velocity of all particles of the rolling object is the same as if it was rotating around an axis that passes through the point of contact with the same angular velocity.

Any point in the rolling object farther from the axis than the point of contact will temporarily move opposite to the direction of the overall motion when it is below the level of the rolling surface (for example, any point in the part of the flange of a train wheel that is below the rail).

Energy

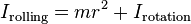

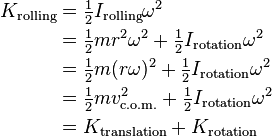

Since kinetic energy is entirely a function of an object mass and velocity, the above result may be used with the parallel axis theorem to obtain the kinetic energy associated with simple rolling:

|

Derivation

Further information: Rotation around a fixed axis

Let |

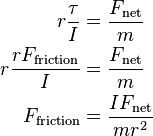

Forces and acceleration

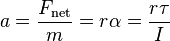

Differentiating the relation between linear and angular velocity,  , with respect to time gives a formula relating linear and angular acceleration

, with respect to time gives a formula relating linear and angular acceleration  . Applying Newton's second law:

. Applying Newton's second law:

.

.

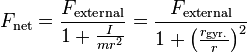

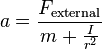

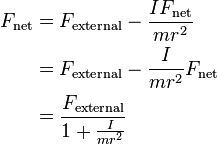

It follows that to accelerate the object, both a net force and a torque are required. When external force with no torque acts on the rolling object‐surface system, there will be a tangential force at the point of contact between the surface and rolling object that provides the required torque as long as the motion is pure rolling; this force is usually static friction, for example, between the road and a wheel or between a bowling lane and a bowling ball. When static friction isn't enough, the friction becomes dynamic friction and slipping happens. The tangential force is opposite in direction to the external force, and therefore partially cancels it. The resulting net force and acceleration are:

|

Derivation

Assume that the object experiences an external force Because there is no slip, Expanding The last equality is the first formula for The radius of gyration can be incorporated in the first formula for Substituting the latest equality above in the first formula for |

has dimension of mass, and it is the mass that would have a rotational inertia

has dimension of mass, and it is the mass that would have a rotational inertia  at distance

at distance  from an axis of rotation. Therefore, the term

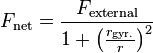

from an axis of rotation. Therefore, the term  may be thought of as the mass with linear inertia equivalent to the rolling object rotational inertia (around its center of mass). The action of the external force upon an object in simple rotation may be conceptualized as accelerating the sum of the real mass and the virtual mass that represents the rotational inertia, which is

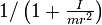

may be thought of as the mass with linear inertia equivalent to the rolling object rotational inertia (around its center of mass). The action of the external force upon an object in simple rotation may be conceptualized as accelerating the sum of the real mass and the virtual mass that represents the rotational inertia, which is  . Since the work done by the external force is split between overcoming the translational and rotational inertia, the external force results in a smaller net force by the dimensionless multiplicative factor

. Since the work done by the external force is split between overcoming the translational and rotational inertia, the external force results in a smaller net force by the dimensionless multiplicative factor  where

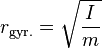

where  represents the ratio of the aforesaid virtual mass to the object actual mass and it is equal to

represents the ratio of the aforesaid virtual mass to the object actual mass and it is equal to  where

where  is the radius of gyration corresponding to the object rotational inertia in pure rotation (not the rotational inertia in pure rolling). The square power is due to the fact that the rotational inertia of a point mass varies proportionally to the square of its distance to the axis.

is the radius of gyration corresponding to the object rotational inertia in pure rotation (not the rotational inertia in pure rolling). The square power is due to the fact that the rotational inertia of a point mass varies proportionally to the square of its distance to the axis.

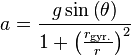

In the specific case of an object rolling in an inclined plane which experiences only static friction, normal force and its own weight, (air drag is absent) the acceleration in the direction of rolling down the slope is:

|

Derivation

Assuming that the object is placed so as to roll downward in the direction of the incline plane (and not partially sideways), the weight can be decomposed in a component in the direction of rolling and a component perpendicular to the incline plane. Only the first force component makes the object roll, the second is balanced by the contact force, but it does not forms an action‐reaction pair with it (just as an object in rest on a table). Therefore, for this analysis, only the first component is considered, thus: In the last equality the denominator is the same as in the formula for force, but the factor |

is specific to the object shape and mass distribution, it does not depends on scale or density. However, it will vary if the object is made to roll with different radiuses; for instance, it varies between a train wheel set rolling normally (by its tire), and by its axle. It follows that given a reference rolling object, another object bigger or with different density will roll with the same acceleration. This behavior is the same as that of an object in free fall or an object sliding without friction (instead of rolling) down an incline plane.

is specific to the object shape and mass distribution, it does not depends on scale or density. However, it will vary if the object is made to roll with different radiuses; for instance, it varies between a train wheel set rolling normally (by its tire), and by its axle. It follows that given a reference rolling object, another object bigger or with different density will roll with the same acceleration. This behavior is the same as that of an object in free fall or an object sliding without friction (instead of rolling) down an incline plane.

References

Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert (2013), Fundamentals of Physics, Chapters 10, 11: Wiley

See also

- Rolling resistance

- Frictional contact mechanics: Rolling contact

- Terrestrial locomotion in animals: Rolling

- Tumbling (gymnastics)

be inertia of

be inertia of  (same as the rotational inertia of pure rotation around the point of contact). Using the general formula for kinetic energy of rotation, we have:

(same as the rotational inertia of pure rotation around the point of contact). Using the general formula for kinetic energy of rotation, we have:

which exerts no torque (it has 0 moment arm), static friction at the point of contact (

which exerts no torque (it has 0 moment arm), static friction at the point of contact ( ) provides the torque and the other forces involved cancell.

) provides the torque and the other forces involved cancell.

holds. Substituting

holds. Substituting  and

and  for the linear and rotational version of Newton's second law, then

for the linear and rotational version of Newton's second law, then  :

:

; using it together with Newton's second law, then

; using it together with Newton's second law, then

disappears because its instance in the force of gravity cancels with its its instance due to Newton's third law.

disappears because its instance in the force of gravity cancels with its its instance due to Newton's third law.