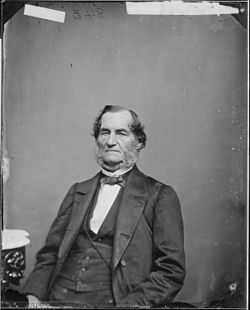

Roger C. Weightman

Roger Chew Weightman (1787 – February 2, 1876) was an American politician, civic leader, and printer. He was the mayor of Washington, D.C. from 1824 to 1827.

Weightman was born in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1787, moving into the new capital in 1800 and taking an apprenticeship with a local printer. Weightman bought the printing business in 1807,[1] making him a congressional printer. He maintained a number of shops on Pennsylvania Avenue, about ten blocks from the White House, from about 1813 onward. In August 1814, Weightman (by now a First Lieutenant in D.C.'s Light Horse Cavalry[2]) was apprehended by the British troops descending on the White House during the Siege of Washington, a battle in the war of 1812, and made to march with them to the Executive Mansion. Admiral George Cockburn taunted the upstanding Washingtonian, forcing him to choose a souvenir (albeit one of no monetary value) to remember the day the American capital was defeated.[3]

After serving seven one-year terms as an alderman on Washington's city council, the council elected Weightman in 1824 to serve out the remainder of the late mayor Samuel N. Smallwood's term. In 1826 he ran against former mayor Thomas Carbery; four years prior, Weightman had run against Carbery for mayor and lost by a narrow margin, but had then pressed the matter in court in a legal battle that lasted until the end of Carbery's term. In 1824, Weightman won more decisively by the use of blustery promises and insults against his opponent. One handbill from the era reads,

NOTICE EXTRAORDINARY. R.C. Weightman, a man of known liberal principles; all those who vote for this gentleman at tomorrow's election, will have general permission to sleep on the Benches in the Market House, this intense warm weather. May the curse of Dr. Slop light on all those who vote for Tom Carberry.[4]

During his time as mayor, Weightman headed the 1825 committee for the inauguration of John Quincy Adams, then the following year chaired the national memorial committee for the president's deceased father and his successor Thomas Jefferson.[5]

In 1827, Weightman became cashier of the Washington Bank, and resigned his position as mayor. He would run again, unsuccessfully, against Walter Lenox in 1850. In the years following his mayoralty, Weightman would be curator of the Columbia Institute; a founding member and officer of the Washington National Monument Society; Grand Master of the Freemasons of the District of Columbia; chief clerk, and later librarian, of the United States Patent Office; and a General in the Union Army during the Civil War — not to mention the center of Washington's social activity.[1]

In addition to his busy social and professional life, Weightman was a noted and generous philanthropist — generous enough that his sizable fortune had dwindled to very little by the 1870s, when Weightman was living on his pension as a soldier and employee of the Patent Office. However, upon his death in February, 1876, his funeral was one of the best attended and most remembered of the era.

Jefferson's Last Letter

The last letter that Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States and the writer of the Declaration of Independence, ever wrote was sent to Roger C. Weightman. It was a letter declining an invitation to join a celebration for the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The letter says:

The kind invitation I receive from you on the part of the citizens of the city of Washington, to be present with them at their celebration of the 50th anniversary of American independence, as one of the surviving signers of an instrument pregnant with our own, and the fate of the world, is most flattering to myself, and heightened by the honorable accompaniment proposed for the comfort of such a journey. It adds sensibly to the sufferings of sickness, to be deprived by it of a personal participation in the rejoicings of that day. But acquiescence is a duty, under circumstances not placed among those we are permitted to controul. I should, indeed, with peculiar delight, have met and exchanged there, congratulations personally with the small band, the remnant of that host of worthies, who joined with us, on that day, in the bold and doubtful election we were to make, for our country, between submission, or the sword; and to have enjoyed with them the consolatory fact that our fellow citizens, after half a century of experience and prosperity, continue to approve the choice we made. May it be to the world what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all), the Signal of arousing men to burst the chains, under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self government. That form which we have substituted restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening to the rights of man. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born, with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God. These are grounds of hope for others. For ourselves, let the annual return of this day forever refresh our recollections of these rights, and an undiminished devotion to them...

Columbian Institute

During the 1820s, Weightman was a member of the prestigious society, Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences, who counted among their members former presidents Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams and many prominent men of the day, including well-known representatives of the military, government service, medical and other professions.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://www.geocities.com/heartland/plains/7347/rogchew2.html

- ↑ Historic Congressional Cemetery - D.C. Schools

- ↑ The White House Historical Association > Research

- ↑ DC ALMANAC: Little known or suppressed facts about the colonial city of Washington DC A-M

- ↑ Belva Lockwood And The 'Way Of The World'

- ↑ Rathbun, Richard. The Columbian institute for the promotion of arts and sciences: A Washington Society of 1816-1838. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, October 18, 1917. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Samuel N. Smallwood |

Mayor of Washington, D.C. 1824–1827 |

Succeeded by Joseph Gales, Jr. |

|