Rodney Marks

Rodney Marks (1968–2000) was an Australian astrophysicist who died from methanol poisoning while working in Antarctica.

Life and death

Marks was born in Geelong, Australia and educated at the University of Melbourne, later obtaining a PhD from the University of New South Wales.[1][2]

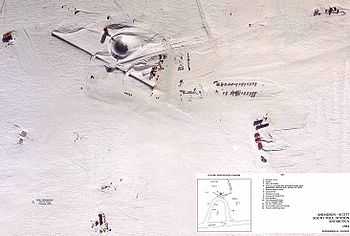

Marks had wintered over at the South Pole station in 1997–1998, before being employed at the South Pole with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, working on the Antarctic Submillimeter Telescope and Remote Observatory, a research project for the University of Chicago at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.[3] He was engaged to Sonja Wolter, who was overwintering as a maintenance specialist at the base in order to be with him.[4] Scott-Amundsen Pole Station is run by the National Science Foundation, a United States government agency, although much work is subcontracted to Raytheon’s Polar Services.

On 11 May 2000 Rodney Marks became unwell while walking between the remote observatory and the base. He became increasingly sick over a 36-hour period, three times returning increasingly distressed to the station's doctor. Advice was sought by satellite, but Marks died on 12 May 2000 with his condition undiagnosed.[5][6] The whereabouts of the station doctor, Robert Thompson, have been unknown sometime after 2006.[7]

The National Science Foundation issued a statement saying that Rodney Marks had "apparently died of natural causes, but the specific cause of death ha[d] yet to be determined".[1] The exact cause of Marks' death could not be determined until his body was removed from Amundsen-Scott Station and flown off the continent for autopsy.[8] The case received media attention as the "first South Pole murder",[9] as suicide was considered the least likely cause of his death.[10]

Investigations into death

Marks' body was held for nearly six months over winter before it could be flown to Christchurch, New Zealand, the base for American activities in Antarctica, for autopsy. Once in New Zealand, a post mortem established that Marks had died from methanol poisoning.[11] Both the United States and Australia agreed to a coroner's inquest being held in New Zealand.[12]

Jurisdiction issues in the Antarctic are complicated;[13] most American operations within Antarctica—including the South Pole base—are within the Ross Dependency territory claimed by New Zealand, from where supplies are dispatched. Without accepting New Zealand’s territorial claim, Americans have not questioned application of New Zealand law to their citizens operating in the Antarctic from Operation Deep Freeze's Christchurch base, while in accordance with the Antarctic Treaty, New Zealand has not questioned the use of U.S. Marshals in relation to crimes involving only Americans in the Ross Dependency.[14]

An investigation was undertaken by Detective Senior Sergeant (DSS) Grant Wormald, of the New Zealand Police, at the direction of Richard McElrea, the Christchurch coroner. A formal verdict has yet to be entered; a 2006 series of Coroners Court hearings and statements to the media raises questions from both the police and the Coroner’s Court if Marks' poisoning was intentional. DSS Wormald said, "In my view it is most likely Marks ingested the methanol unknowingly."[15][16]

Marks had Tourette syndrome. DSS Wormald stated it was not credible to believe he had accidentally drunk the methanol, when he had ready access to a large supply of alcohol. Marks had recently entered a new relationship, had nearly completed important academic work and had no financial problems. He had promptly sought treatment for an illness that confused him, and there was no reason to suspect suicidal intent.[17]

DSS Wormald indicated that Raytheon and the National Science Foundation had not been cooperative.[16] DSS Wormald stated regarding the NSF conclusion that Marks' death was from natural causes: "We wanted the results of [the NSF] internal investigation and to get in contact with people who were there to ask them some questions," said Wormald. "They weren't prepared to tell us who was there "... "they have advised that no report exists. To be frank, I think there is more there; there must be",[16] Wormald said. "I am not entirely satisfied that all relevant information and reports have been disclosed to the New Zealand police or the coroner".[9]

Having obtained details of the 49 other people at the base at the time, DSS Wormald told a newspaper, "I suspect that there have been people who have thought twice about making contact with us on the basis of their future employment position".[16] The U.S. Department of Justice also failed to obtain answers from the two organisations, which appeared to have denied jurisdiction.[9][10][16]

In December 2006 the Christchurch Coroner reconvened the investigation, the results of which were widely reported;[10][16][17] the coroner's hearing in Christchurch was then adjourned indefinitely.[18] Marks' father thanked the New Zealand police, who he said faced an "arduous task of dealing with people that quite obviously don't want to deal with them".[17]

In January 2007, seven years after the death, the case was again front page news in New Zealand, when documents obtained under America's Freedom of Information Act suggested "diplomatic heat was brought to bear on the NZ inquiry".[12]

In September 2008, the written report resulting from the December 2006 inquest was released. The coroner could not find evidence to support theories of a prank gone awry nor foul play nor suicide.[19][20][21]

The cause of the fatal methanol poisoning has never been determined, and the Marks family has given up hope of learning what happened. Paul Marks, Rodney's father, is quoted as saying "...And I don't think we are going to try to find out any more in regards to how Rodney died. I'd see that as a fruitless exercise."[22]

Memorial

Mount Marks, a mountain in the Worcester Range with a height of 2,600 metres (8,530 ft) (78°47′S, 160°35′E) is named after Marks. A plaque was erected at the base, and the site of the South Pole in January 2001 is marked by a memorial to him.[6][23][24]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Antarctic Researcher Dies". National Science Foundation Office of Legislative and Public Affairs, Press release 12 May 2000. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Rodney Marks (1968 - 2000) at the Wayback Machine (archived March 20, 2012). Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Center for Astrophysical Research in Antarctica, 23 August 2000. Rodney Marks: (1968 - 2000). Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Murder at the South Pole: Antarctic scientist's death investigated. ohmynews.com, 21 December 2006. Retrieved on 1 April 2007.

- ↑ Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "In Memoriam". The CfA Almanac Vol. XIII No. 2, July 2000. Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Memorial. Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Mervis, Jeffrey. "A Death in Antarctica". Science. 2 Jan 2009, vol. 323. p. 34. Retrieved on 2009-06-02.

- ↑ "Australian scientist dies during Pole winter". The Antarctic Sun 22 October 2000. Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Chapman, Paul (14 December 2006). "New Zealand Probes What May Be First South Pole Murder". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2007-03-27. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hayman, Kamala (9 December 2006). "Death in Antarctica to be revisited". stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ Hayman, Kamala (9 December 2006). "Death in Antarctica to be revisited". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "South Pole Death Mystery — Who killed Rodney Marks". Sunday Star Times. 21 January 2007.

- ↑ Bilder, Richard B (1966). [Scholar search "Control of criminal conduct in Antarctica"]. Virginia Law Review (Virginia Law Review) 52 (2): 231–285. doi:10.2307/1071611. JSTOR 1071611. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ↑ "U.S. Marshals make legal presence in Antarctica.". United States Marshals Service. 5 January 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- ↑ "Aussie may have been poisoned". 70South Antarctic News. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Hotere, Andrea (17 December 2006). "South Pole death file still open". Sunday Star Times. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Booker, Jarrod (14 December 2006). "South Pole scientist may have been poisoned". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ↑ "Inquest adjourned indefinitely". Television New Zealand. Newstalk ZB. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ↑ "Mystery remains over death of Australian at South Pole". www.radioaustralia.net.au. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ↑ "Circumstances of Aust scientist's South Pole death still unclear". www.abc.net.au. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ↑ "Scientist's death in Antarctica remains a mystery". tvnz.co.nz. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ↑ Booker, Jarrod (25 September 2008). "NZ probe into death hits icy wall". www.nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ↑ Americans honour Antarctic veterans. newzeal.com, (19 December 2001). Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

- ↑ South Pole 2001 at the Wayback Machine (archived December 6, 2009). mountainclimb.com. Retrieved on 19 December 2006.

Further reading

- Glanz, James. "Scientist Dies At South Pole Research Site". New York Times. New York, N.Y.: 17 May 2000. p. A.15. Retrieved on 2007-12-07.

- Mervis, Jeffrey. "A Death in Antarctica". Science. 2 Jan 2009, vol. 323. p. 32. Retrieved on 2009-06-02.