Rock of Solutré

| Roche de Solutré | |

|---|---|

|

La Roche de Solutré | |

| Elevation | 493 |

| Location | |

| Location |

|

| Range | Monts du Mâconnais |

| Coordinates | 46°17′57″N 4°43′9″E / 46.29917°N 4.71917°ECoordinates: 46°17′57″N 4°43′9″E / 46.29917°N 4.71917°E |

The Rock of Solutré (French: Roche de Solutré), is a limestone escarpment 8 km (5.0 mi) west of Mâcon overlooking the commune of Solutré-Pouilly and an iconic site of the Saône-et-Loire, in the south of the Bourgogne in France. Protected by the French law on sites classés and currently at the heart of a Grand Site National operation, it draws its fame severally as a rare geological phenomenon of the region, as a prehistoric site of the eponymous Solutrean paleolithic culture, and for the natural environment which it summit provides, the pelouse calciole grassland of Mâcon, with its distinctive flora and fauna. Occupied by man for at least 55,000 years, it is also the cradle of the Pouilly-Fuissé wine appellation. It has attracted media coverage since the 1980s when French President François Mitterrand started to make ritual ascents of the peak once per year.

Geography

Formation

In the Mesozoic era warm seas extended over the region, of which many fossil remains can be readily observed. The Roche de Solutré, like its neighbour the Rock of Vergisson, was created from fossilized coral plateaux which appeared approximately 160 million years ago in these seas.

In the Cenozoic era, the east of Bourgogne underwent the effects of the Alpine rising; while the Alps grew higher, the Saône basin collapsed. At the same times, plateaux rose in the west of the plain, then rocked towards the east.

These processes had mixed up types of land with different natural composition, and erosion acted on them differently. The shapes of the surrounding mountains became more curved, while the cliffs of Soulutré and Vergisson have emerged on the west side, contrasting with the gentle slopes on their east.

Countryside

Surrounded by vineyards, the rock hosts a varied and spectacular country, from the height of its rocky peak or its grassy slopes. The Saône plain extends to the east, with a view of Mâconnais in the foreground, then Ain and Dombes against the backdrop of the Alps and Mont Blanc in good visibility.

In the three other directions the countryside is less open and bounded by the lines and crests of surrounding hills, with vineyards, villages, and typical Mâconnais settlements, in particular:

- to the north among the hills and vineyards, the village of Vergisson and its own outcrop ;

- to the west, the Roman road, and beyond, a mixed area of vineyards, groves and forests ;

- to the south, the village of Solutré-Pouilly and the Mont de Pouilly.

Prehistory

Solutré's remains from prehistoric times are some of the richest in Europe in bones and stone artifacts. Following their discovery, the Rock gave its name to a culture of the Upper Paleolithic, the Solutrean.

Chronology

Excavations at the foot of the rock started in 1866, at the place called the "Cros du Charnier" on the protrusion of horse bones, which no-one imagined at the time would date to prehistory, a science which was only emerging at the time.

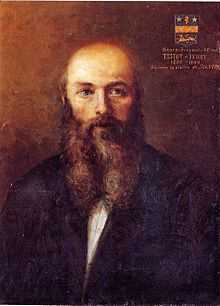

The zone of Upper Paleolithic homes was quickly discovered by Henry Testot-Ferry, along with some tombs of raw slabs. In the homes, numerous flint tools were found, including spear-points, choppers and other scrapers, and also a large hoard of bones, mainly from reindeer but also from horse, elephant, wolf and cave tiger.

Testot-Ferry and Adrien Arcelin decided to see if they could determine scientifically how large the deposit was that they had brought to light, and to examine with great care the remains that they had recovered. The challenge was to understand the arrangement of stratigraphic areas of the site, which would be the basis for establishing a chronology.

In 1868, the existence of a station for foot-based hunters was the preferred scientific hypothesis. The two discoverers called on specialists and presented their work at conferences. Solutré was revealed as one of the greatest prehistoric sites in France.

In 1872, Gabriel de Mortillet, one of the most important prehistorians of his time, decided to name prehistoric periods after sites where they were particularly well presented. Thus the term "Solutrean" was born.

Numerous excavations were conducted thereafter. The excavation site remains protected, and partially unexplored, to this day.

Hunting site

The height of the sites in relation to the flood plain was the most important factor for human habitation. Providing shelter and food for migrant groups, the foot of the rock, strewn with debris, afforded hunters the opportunity to develop traps.

The bone-laden magma can be explained by the fact that the site was used by four great paleolithic civilizations over the 25,000 years from 35,000 to 10,000 B.C, an extremely long time period.

The use of this site was therefore devoted to hunting activity, butchering and smoking meat, while the neighbouring Rock of Vergisson was a site for habitation. The material found at Solutré was therefore linked with hunting; many tools were found including the flints cut in the shape of bay leaves which are characteristic of Solutrean culture.

Contrary to the legend of the "hunt into the abyss", prehistoric man of Solutré region never hunted horses by driving them off the rock. This theory, which was never brought by Testot-Ferry, in his scientific publications, in fact appeared in Arcelin's prehistory-based novel, "Solutré" (Paris 1872); it has never been other than a fiction which caught the popular imagination. The incongruity of this hypothesis was easily shown from the distance between the bones and the summit of the rock, among other considerations.

Another legend told that the dog's domestication was made in Solutré where wolves cooperated with humans during "hunt into the abyss. This was also falsified in as the first domestic dog has been found in the Altai Mountains and dated 33,000 B.C.

Human remains

Testot-Ferry and Arcelin also brought to light some human remains at Cros du Charnier. In all, by the end of the period of excavations between about 1866 and 1925, almost 70 skeletons had been recovered. Although at the time of the first excavations the corpses were considered as prehistoric (Aurignacians and Neolithics), it has since become almost certain that some of the skeletons are historical. According to different datings, they appear to be Burgundians (from the high Middle Ages) or Merovingians.

Paradoxically, despite the length of time when the site was in use, the Solutrean era was the only period in the Upper Paleolithic from which there are no human remains. Ultimately, one year after the first excavations carried out at the rock, remains of Cro-magnon man were discovered at Eyzies by Louis Lartet. The Cro-magnons were contemporaries of the culture who had cut tools and hunted at Solutré.

Museum

The departmental history museum, a structure designed by the architect Guy Clapot from Strasbourg, is situated at the foot of the rock. The museum was encouraged by French President François Mitterrand, and was opened in 1987. Because of regulations in force at the site, the museum lies beneath a dome planted with vegetation, and is hardly visible from a distance. The places where the discoveries were made are presented in the museum along with a reconstructions of scenes from the hunt. The museum also hosts temporary exhibitions on subjects related to archeology, prehistory and ethnography.

From antiquity to the modern day

The rock's surroundings have been occupied continuously since pre-history, each epoch leaving its mark although sometimes almost invisible to the naked eye.

Antiquity

Traces have been discovered of two important Gallo-Roman villas near the rock. One, Solustriacus, gave its name to the village of Solutré. The other would have been situated between the rock and the neighbouring village of Vergisson. A large flattened mound linking the foot of the rock with Vergisson is suggested to be an ancient Roman road, and is referred to as such by locals.

Post-antiquity

In the Middle Ages, the Rock of Solutré was a powerful high point, reputed to be the domain of bandits. After the truce signed in Mâcon on 4 December 1434 accepting the Burgundian presence in Mâconnais, this castle, the only remaining high place in the region not reduced by the Duke of Burgundy, was handed over to him. The following year the Duke, Jean le Bon, ordered the total destruction of the fortress by an act passed at Dijon on 22 December 1434. There was such popular jubilation at the pronouncement that bodies have been found of participants in the destruction, killed by the disorderly collapse of the walls. Recent research has shown that the castle had been a noble and wealthy dwelling, but few facts are known about its residents.

A high place for the French Resistance during World War II, the rock was ritually climbed each year by President François Mitterrand and certain of his friends.

A particular habitat: the pelouses calcicoles of Mâconnais

Human activities on and around the rock have had a visible impact on its profile. From the deforestation of the original Gaulish forest to the plantation of the first vineyards, to contemporary polyculture and current monoculture of wine production, the countryside has been shaped and changed.

The clearing at the peak and the soft slopes of the rock have contributed to the appearance and maintenance of a local habitat. In fact, until the middle of the 19th century, the wives of farmers herded their goats on these parcels of land surrounded by dry stone walls. This pasturing as well as the practice of burning maintained the dry grass which had developed, hosting numerous rare or protected plant and animal species, who found their most northerly home.

The pelouses calcicoles, also known as pelouses calcaires are also found on four other peaks formed in the same epoch (from north to south: Monsard, Mont de Leynes, the Rock of Vergisson, and finally Mont de Pouilly to the south of Solutré). They are protecteded under the French protections and sustainable development rules. When pasturing ceased after the Second World War, the area was colonized by boxtree, juniper and pedunculate oak.

Flora include inula, hippocrepis emerus, Bombycilaena erecta, wild orchid, hippocrepis comosa. Mountain and Mediterranean species which share the rock include festuca, carex, bromus, helianthemum, silene, rubia peregrina, Œillet (which can refer to several species), sesleria caerulea, sedum and saxifrage.

Notable birds of the rock include the ortolan bunting, the scops-owl, the European nightjar, the short-toed snake eagle, the northern harrier and the woodlark. Notable insects include the scarce swallowtail, the praying mantis and the Mediterranean cricket.

Viticulture

Introduced by the Romans, viticulture was practiced in the Middle Ages by Cluniac monks and penetrated the perimeter of the rock. Their phases of ebb and flow over the centuries entailed in turn the clearing of plots of land or their abandonment to the countryside. The area's predilection for Chardonnay has given rise to wines with international reputations:[1]

- Mâcon-Solutré (Mâcon-Villages)

- Saint-Véran

- Pouilly-Fuissé

Protection and sustainable development

The Rock had been partially protected by the law of 2 May 1930 on the protection of natural monuments and sites of artistic, historic, legendary or picturesque character, by virtue of the its spectacular aspect and the archeological sites which it sheltered, and was part of the Natura 2000 network in the context of its pelouses calcioles grassland. These protections have turned out to be insufficient in the face of heavy visitation by locals and tourists, and the usure created on the site, and maintenance costs which are too heavy for the local communes.

From the 1990s the Rock has been officially made the focus of an Operation Grand Site. This law does not add any regulatory constraints but constitutes a tool for restauring and bringing value to the site, setting up a reception, and generating a dynamic local economy and a continuing management of the area.

Since 1995 trials have taken place to maintain the site as is involving e.g. grazing by Konik Polski horses and fighting colonization by boxtree through pasturing. The pathways have been revised to enhance safety for visitors and to stop the degradation of tracks, the parking lot has made way for a new one, which integrates almost completely with the landscape.[2]

Anecdotes

The 2009 Michelin guide for Bourgogne, in its article on the Rock of Solutré, mistakenly displayed a photograph of the Rock of Vergisson.

Well-known quotations concerning the rock

- Sphinx aux griffes plantées dans les ceps (A Sphinx with claws planted in the vines)

- Deux navires pétrifiés surplombant une mer de vignes (Two petrified ships overlooking a sea of vineyards) Alphonse de Lamartine, speaking of the two rocks of Solutré Vergisson

- De là, j'observe ce qui va, ce qui vient, ce qui bouge et surtout ce qui ne bouge pas. (From there, I watch that which goes, that which comes, that which moves, and overall that which does not move) François Mitterrand in La Paille et le Grain, 1978.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solutré-Pouilly. |

- (French) France's Grands Sites network

- (French) Definition of an Opération Grand site (OGS) on the French Ministry of Ecology and Sustainable Development Website

- Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

References

- ↑ For more detail, see Burgundy wine

- ↑ (French) For more information see The official website of Grand Site de Solutré Pouilly Vergisson

Bibliography

- (French) Paléontologie française, Henry de Ferry & Dr. de Fromentel, Paris, 1861

- (French) L'Homme préhistorique en Mâconnais, Henry de Ferry, 1868

- (French) Le Mâconnais préhistorique, Henry de Ferry, Paris, 1870

- (French) Solutré ou les chasseurs de rennes de la France centrale, Adrien Arcelin, Paris, 1872

- (French) Les fouilles de Solutré, Adrien Arcelin, Mâcon, 1873

- (French) Annales de l'Académie de Mâcon, 1869–1906

- (French) 1866 : l'invention de Solutré, 1989 Summer exhibition catalogue of the Musée Départemental de Préhistoire de Solutré

- (French) Solutré, 1968–1998, Jean Combier et Anta Montet-White (dir.), (2002), Mémoire de la Société Préhistorique française XXX, ISBN 2-913745-15-6