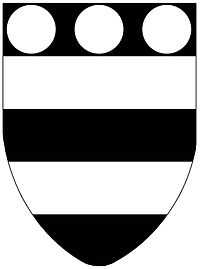

Robert Hungerford, 3rd Baron Hungerford

Robert Hungerford, 3rd Baron Hungerford (1431–1464) was an English nobleman. He supported the Lancastrians cause in the War of the Roses. In the late 1440s and early 1450s he was a member of successive parliaments. He was a prisoner of the French for much of the 1450s until his mother arranged a payment of a 7,966l ransom. In 1460 after successive defeats on the battlefield he fled with Henry VI to Scotland. In 1461 he was attainted in Edward IV's first parliament, and executed in Newcastle soon after he was captured at the Battle of Hexham.

Early life

Hungerford was son and heir of Robert Hungerford, 2nd Baron Hungerford, and was grandson of Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford (died 1449).[1] Hungerford was summoned to parliament as Baron Moleyns in 1445, sui uxoris (in the right of his wife), Alianore or Eleanor, the great-great-granddaughter of John, baron de Molines or Moleyns (died 1371). Hungerford received a like summons until 1453.[1]

Dispute with John Paston

In 1448 Hungerford began a fierce quarrel with John Paston regarding the ownership of the manor of Gresham in Norfolk. Hungerford, acting on the advice of John Heydon, a solicitor of Baconsthorpe, took forcible possession of the estate on 17 February 1448. William Waynflete, bishop of Winchester, made a vain attempt at arbitration. Paston obtained repossession, but on 28 January 1450 Hungerford sent a thousand men to dislodge him. After threatening to kill Paston, who was absent, Hungerford's adherents violently assaulted Paston's wife Margaret, but Hungerford finally had to surrender the manor to Paston.[2]

French wars

In 1452 Hungerford accompanied John Talbot, 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury, to Aquitaine, and was taken prisoner while endeavouring to raise the siege of Chastillon. His ransom was fixed at 7,966l., and his mother sold her plate and mortgaged her estates to raise the money. His release was effected in 1459, after seven years and four months' imprisonment. In consideration of his misfortunes he was granted, in the year of his return to England, license to export fifteen hundred sacks of wool to foreign ports without paying duty, and received permission to travel abroad. He thereupon visited Florence.[1]

Wars of the Roses

In 1460 Hungerford was home again, and took a leading part on the Lancastrian side in the Wars of the Roses. In June 1460 he retired with Lord Scales and other of his friends to the Tower of London, on the entry of the Earl of Warwick and his Kentish followers into the city; but after the defeat of the Lancastrians at the battle of Northampton (10 July 1460), Hungerford and his friends surrendered the Tower to the Yorkists on the condition that he and Lord Scales should depart free,[3]

After taking part in the battle of Towton (29 March 1461)—a further defeat for the Lancastrians—Hungerford fled with Henry VI to York, and thence into Scotland. He visited France in the summer to obtain help for Henry and Margaret, and was arrested by the French authorities in August 1461. Writing to Margaret at the time from Dieppe, he begged her not to lose heart.[4] He was attainded in Edward IV's first parliament in November 1461. He afterward met with some success in his efforts to rally the Lancastrians in the north of England, but was taken prisoner at the Battle of Hexham on 15 May 1464, and was executed at Newcastle. He was buried in Salisbury Cathedral. On 5 August 1460 many of his lands were granted to Richard, Duke of Gloucester (afterward Richard III). Other portions of his property were given to Lord Wenlock, who was directed by Edward IV to make provision for Hungerford's wife and young children.[5]

Marriage and children

Hungerford married at a very early age (about 1441) Alianore or Eleanor (b. 1425), daughter and heiress of Sir William de Molines or Moleyns (d. 1428).[1] They had two children:[5]

Eleanor, Baroness Moleyns, survived her husband and subsequently married Sir Oliver de Manningham. She was buried at Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire.[5]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lee 1891, p. 256.

- ↑ Lee 1891, p. 256 Citing Paston Letters, ed. Gairdner, i. xxxi, lxix, 75-6, 109-12, 221-3, iii. 449.

- ↑ Lee 1891, pp. 256–257 Cites: William of Worcester [772-3], Lee states that "the year is wrongly given as 1459".

- ↑ Lee 1891, p. 257 cites: Paston Letters, ii. 45-6, 93.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Lee 1891, p. 257.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney (1891). "Hungerford, Robert". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 256, 257. Endnotes

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney (1891). "Hungerford, Robert". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 28. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 256, 257. Endnotes

- Dugdale's Baronage ;

- Hoare's Hungerfordiana ;

- Letters, &c., of Henry VIII;

- Materials for the Keign of Henry VII (Eolls Ser.) ;

- Paston Letters, passim, ed. G-airdner;

- Hoare's Mod. "Wiltshire, Heytesbury Hundred

- Collinson's Somerset, iii. 355.