Roanoke Colony

Coordinates: 35°55′42″N 75°42′15″W / 35.928259°N 75.704098°W

| Roanoke Colony | |||||

| Colony of Kingdom of England | |||||

| |||||

| | |||||

| History | |||||

| - | Sir Walter Raleigh establishes colony | 1585 | |||

| - | birth of Virginia Dare | August 18, 1587 | |||

| - | abandoned sometime before August 1590 | 1587–1590 | |||

| - | Found abandoned | August 18, 1590 | |||

| Population | |||||

| - | 1587 | 116 | |||

| Political subdivisions | English Colony | ||||

| Today part of | - | ||||

The Roanoke Colony, also known as the Lost Colony, established on Roanoke Island, in what is today's Dare County, North Carolina, United States, was a late 16th-century attempt by Queen Elizabeth I to establish a permanent English settlement. The enterprise was originally financed and organized by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who drowned in 1583 during an aborted attempt to colonize St. John's, Newfoundland. Sir Humphrey Gilbert's half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, later gained his brother's charter from the Queen and subsequently executed the details of the charter through his delegates Ralph Lane and Richard Grenville, Raleigh's distant cousin.[1]

The final group of colonists disappeared during the Anglo-Spanish War, three years after the last shipment of supplies from England. Their disappearance gave rise to the nickname "The Lost Colony." To this day there has been no conclusive evidence as to what happened to the colonists.

Raleigh's charter

On March 25, 1584, Queen Elizabeth I granted Raleigh a charter for the colonization of the area of North America. This charter specified that Raleigh needed to establish a colony in North America, or lose his right to colonization.[2]:9

Raleigh and Elizabeth intended that the venture should provide riches from the New World and a base from which to send privateers on raids against the treasure fleets of Spain.[3]:135 Raleigh himself never visited North America, although he led expeditions in 1595 and 1617 to South America's Orinoco River basin in search of the legendary golden city of El Dorado.

First voyages to Roanoke Island

On April 27, 1584, Raleigh dispatched an expedition led by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to explore the eastern coast of North America. They arrived on Roanoke Island on July 4,[2]:32 and soon established relations with the local natives, the Secotans and Croatoans. Barlowe returned to England with two Croatoans named Manteo and Wanchese, who were able to describe the politics and geography of the area to Raleigh.[2]:44–45 Based on this information, Raleigh organized a second expedition, to be led by Sir Richard Grenville.

Grenville's fleet departed Plymouth on April 9, 1585, with five main ships: the Tiger (Grenville's), the Roebuck, the Red Lion, the Elizabeth, and the Dorothy. Unfortunately, a severe storm off the coast of Portugal separated the Tiger from the rest of the fleet.[2]:57 The captains had a contingency plan if they were separated, which was to meet up again in Puerto Rico, and the Tiger arrived in the "Baye of Muskito"[4] (Guayanilla Bay) on May 11.

While waiting for the other ships, Grenville established relations with the native Spanish while simultaneously engaging in some privateering against them.[2]:62 He also built a fort. The Elizabeth arrived soon after the fort's construction.[5]:91 Eventually, Grenville tired of waiting for the remaining ships, and departed on June 7. The fort was abandoned, and its location remains unknown.

When the Tiger sailed through Ocracoke Inlet on June 26, it struck a shoal, ruining most of the food supplies.[2]:63 The expedition succeeded in repairing the ship, and in early July reunited with the Roebuck and Dorothy, which had arrived in the Outer Banks with The Red Lion some weeks previous. The Red Lion had dropped off its passengers and left for Newfoundland for privateering.[2]:64

During the initial exploration of the mainland coast and the native settlements, the Europeans blamed the natives of the village of Aquascogoc for stealing a silver cup. As retaliation, the settlers sacked and burned the village.[2]:72 English writer and courtier Richard Hakluyt's contemporary reports of the first voyage to Roanoke, compiled from accounts by various financial backers including Sir Walter Raleigh (Hakluyt himself never traveled to the New World), also describe this incident.[6]

Despite this incident and a lack of food, Grenville decided to leave Ralph Lane and 107 men to establish a colony at the north end of Roanoke Island, promising to return in April 1586 with more men and fresh supplies. They disembarked on August 17, 1585[7] and built a small fort on the island. There are no surviving pictures of the Roanoke fort, but it was likely similar in structure to the one in Guayanilla Bay.

As April 1586 passed, there was no sign of Grenville's relief fleet. Meanwhile in June, bad blood resulting from their destruction of the village spurred an attack on the fort, which the colonists were able to repel.[8]:5 Soon after the attack, when Sir Francis Drake paused on his way home from a successful raid in the Caribbean and offered to take the colonists, including the metallurgist Joachim Gans, back to England, they accepted. On this return voyage, the Roanoke colonists introduced tobacco, maize, and potatoes.[8]:5 The relief fleet arrived shortly after Drake's departure with the colonists. Finding the colony abandoned, Grenville returned to England with the bulk of his force, leaving behind a small detachment both to maintain an English presence and to protect Raleigh's claim to Roanoke Island.

The Lost Colony

In 1587, Raleigh dispatched a new group of 115 colonists to establish a colony on Chesapeake Bay. They were led by John White, an artist and friend of Raleigh who had accompanied the previous expeditions to Roanoke. White was later appointed Governor and Raleigh named 12 assistants to aid in the settlement. They were ordered to travel to Roanoke to check on the settlers, but when they arrived on July 22, 1587, they found nothing except a skeleton that may have been the remains of one of the English garrison.[6]

When they could find no one, [6] the fleet's commander, Simon Fernandez, refused to let the colonists return to the ships, insisting they establish the new colony on Roanoke.[5]:215 His motive remains unclear.

White re-established relations with the Croatans and local tribes, but those with whom Lane had fought previously refused to meet with him. Shortly thereafter, colonist George Howe was killed by a native while searching alone for crabs in Albemarle Sound.[9]:120–23

Fearing for their lives, the colonists persuaded Governor White to return to England to explain the colony's desperate situation and ask for help.[9]:120–23 Left behind were about 115 colonists – the remaining men and women who had made the Atlantic crossing plus White's newly born granddaughter Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the Americas.[10]:19

White returns to England

White sailed for England in late 1587. Crossing the Atlantic at that time of year was a considerable risk.[11] Plans for a relief fleet were delayed first by the captain's refusal to return during the winter, and then the coming of the Spanish Armada and the subsequent Anglo-Spanish War, which led to every able English ship joining the fight, leaving White without a means to return to Roanoke.[3]:125–26

In the spring of 1588, White managed to hire two small vessels and sailed for Roanoke; however, his attempt to return was thwarted when the captains of the ships attempted to capture several Spanish ships on the outward-bound voyage to improve their profits. They were captured themselves and their cargo seized. With nothing left to deliver to the colonists, the ships returned to England.[3]:125–26

Because of the continuing war with Spain, White was unable to mount another resupply attempt for three more years. He finally gained passage on a privateering expedition that agreed to stop off at Roanoke on the way back from the Caribbean. White landed on August 18, 1590, on his granddaughter's third birthday, but found the settlement deserted. His men could not find any trace of the 90 men, 17 women, and 11 children, nor was there any sign of a struggle or battle.[3]:130–33

The only clue was the word "Croatoan" carved into a post of the fence around the village and "Cro" carved into a nearby tree. All the houses and fortifications had been dismantled, which meant their departure had not been hurried. Before he left the colony, White instructed them that if anything happened to them, they should carve a Maltese cross on a tree nearby, indicating their disappearance had been forced. As there was no cross, White took this to mean they had moved to "Croatoan Island" (now known as Hatteras Island), but he was unable to conduct a search. A massive storm was forming and his men refused to go any farther; the next day they left.[3]:130–33

Thomas Harriot

Born in 1560, Thomas Harriot entered Raleigh's employment in the early 1580s, after graduating from Oxford University. While he did not accompany them on the first voyage, Harriot may have been among the men of Arthur Barlowe's 1584 expedition of the colony. He trained the members of Raleigh's first Roanoke expedition in navigational skills and eventually sailed to Roanoke with the second group of settlers, where his skills as a naturalist became particularly important along with those of painter and settlement leader John White.[12]

Between their arrival in Roanoke in April 1585 and the July 1586 departure, Harriot and White both conducted detailed studies of the Roanoke area, with Harriot compiling his samples and notes into several notebooks that unfortunately did not survive the colony's disappearance. However, Harriot also wrote descriptions of the surrounding flora and fauna of the area, which survive in his work A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, written as a report on the colony's progress to the English government on the request of Raleigh. Viewed by modern historians as propaganda for the colony, this work has become vastly important to Roanoke's history due to Harriot's observations on wildlife as well as his depictions of Indian activities at the time of the colony's disappearance.[12]

Harriot reports that relations between the Roanoke Indians and the English settlers were mutually calm and prosperous, contradicting other historical evidence that catalogs the bloody struggles between the Roanoke Indians and both of Raleigh's commanders, Sir Richard Grenville and his successor Ralph Lane. Harriot recounts little to none of these accounts in his report to England and does not mention the disorderly state of the colony under either Grenville's or Lane's tenure, correctly assuming these facts would prevent Roanoke from gaining more settlers. Ironically, Harriot's text did not reach England, or the English press, until 1588, by which time the fate of the "Lost Colony" was sealed in all but name.[12]

Investigations into Roanoke

Twelve years went by before Raleigh decided to find out what happened to his colony. Led by Samuel Mace, this 1602 expedition differed from previous voyages in that Raleigh bought his own ship and guaranteed the sailors' wages so that they would not be distracted by privateering. However, Raleigh still hoped to make money from the trip, and Mace's ship landed in the Outer Banks to gather aromatic woods or plants such as sassafras that would generate a decent profit back in England. By the time they could turn their attention to the colonists, the weather had turned bad and they were forced to return without even making it to Roanoke Island. Having been arrested for treason, Raleigh was unable to send any further missions.[3]:134–35

Meanwhile, the Spanish had different reasons for wanting to find the colony. Knowing of Raleigh's plans to use Roanoke as a base for privateering, they were hoping to destroy it. Moreover, they had been getting mostly inaccurate reports of activities there, and they imagined the colony to be far more successful than it really was.[3]:135–37

In 1590, they found the remnants of the colony purely by accident, but assumed it was only an outlying base of the main settlement, which they believed was in the Chesapeake Bay area (John White's intended location). But just as the Anglo-Spanish War prevented White from returning in a timely manner, Spanish authorities in the New World could not muster enough support back home for such a venture.[3]:135–37

Hypotheses about the disappearance

The end of the 1587 colony is unrecorded, leading to the colony being referred to as the "Lost colony", with multiple hypotheses existing as to the fate of the colonists.

Reports of John Smith and William Strachey regarding the "Lost Colony"

Once the Jamestown settlement was established in 1607, efforts were undertaken by the English to acquire information from the Powhatan tribe about the 1587 Lost Colony. The first definitive information concerning the fate of the Lost Colony came from Captain John Smith, leader of the Jamestown Colony from 1608 to 1609. According to chronicler Samuel Purchas, Smith learned from Wahunsunacock, known to the English as Chief Powhatan, that he had personally conducted the slaughter of the Lost Colonists. This shocking information was reported to England and by the spring of 1609 King James and the Royal Council were convinced that Chief Powhatan was responsible for the slaughter of the Lost Colony.

The second source of Chief Powhatan’s involvement in the fate of the Lost Colony was William Strachey, Secretary of the Jamestown colony in 1610-11. Strachey’s The Historie of Travaile Into Virginia Britannia seemed to confirm Smith’s report and provided additional information: The colonists had been living peacefully among a group of natives (see Chesepians below) beyond Powhatan’s domain for more than twenty years when they were massacred. Furthermore, Powhatan himself seemed to have directed the slaughter because of prophesies by his priests, and the slaughter took place about the same time that Christopher Newport arrived at the Chesapeake Bay with the Jamestown settlers on April 26, 1607. Rumors about possible survivors of the massacre led to several search expeditions, but no trace of the Lost Colony has ever been found.

The information from these two sources, John Smith and William Strachey, provided the basis for the established conviction that the Lost Colony had been slaughtered by Chief Powhatan, and versions of the Powhatan-Lost Colony-slaughter scenario have persisted for more than 400 years. Recent re-examination of the Smith and Strachey sources advanced by researcher Brandon Fullam has suggested that there were actually two slaughters described in Strachey’s Historie and that the 1587 Lost Colony was not involved in any way with either one.

Integration with local tribes

In her 2000 book Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony, historian Lee Miller postulated that some of the Lost Colony survivors sought shelter with the Chowanoke, who were attacked by another tribe, identified by the Jamestown Colony as the "Mandoag" (an Algonquian name commonly given to enemy nations). The "Mandoag" are believed to be either the Tuscarora, an Iroquois-speaking tribe,[13]:45 or the Eno, also known as the Wainoke.[10]:255–56

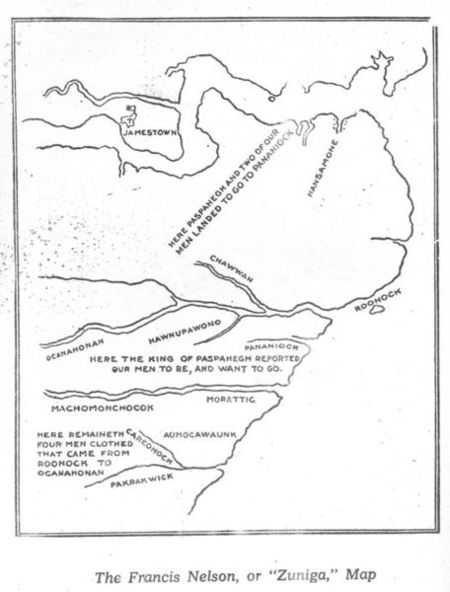

The so-called "Zuniga Map" (named for Pedro de Zúñiga, the Spanish ambassador to England, who had secured a copy and passed it on to Philip III of Spain[14]:112), drawn about 1607 by the Jamestown settler Francis Nelson, also gives credence to this claim. The map states "four men clothed that came from roonock" were living in an Iroquois site on the Neuse. William Strachey, a secretary of the Jamestown Colony, wrote in his The historie of travaile into Virginia Britannia in 1612 that, at the Indian settlements of Peccarecanick and Ochanahoen, there were reportedly two-story houses with stone walls. The Indians supposedly learned how to build them from the Roanoke settlers.[15]:222

There were also reported sightings of European captives at various Indian settlements during the same time period.[10]:250 Strachey wrote in 1612 that four English men, two boys and one girl had been sighted at the Eno settlement of Ritanoc, under the protection of a chief called Eyanoco. Strachey reported that the captives were forced to beat copper and that they had escaped the attack on the other colonists and fled up the Chaonoke river, the present-day Chowan River in Bertie County, North Carolina.[10]:242[15]:222[16] For four hundred years, various authors have speculated that the captive girl was Virginia Dare.

John Lawson wrote in his 1709 A New Voyage to Carolina that the Croatans living on Hatteras Island used to live on Roanoke Island and claimed to have white ancestors:

A farther Confirmation of this we have from the Hatteras Indians, who either then lived on Ronoak-Island, or much frequented it. These tell us, that several of their Ancestors were white People, and could talk in a Book, as we do; the Truth of which is confirm'd by gray Eyes being found frequently amongst these Indians, and no others. They value themselves extremely for their Affinity to the English, and are ready to do them all friendly Offices. It is probable, that this Settlement miscarry'd for want of timely Supplies from England; or thro' the Treachery of the Natives, for we may reasonably suppose that the English were forced to cohabit with them, for Relief and Conversation; and that in process of Time, they conform'd themselves to the Manners of their Indian Relations.[17]

From the early 17th century to the middle 18th century, European colonists reported encounters with gray-eyed American Indians who claimed descent from the colonists[10]:257, 263 (although at least one, a story of a Welsh priest who met a Doeg warrior who spoke the Welsh language, is likely to be a hoax).[18]:76 Records from French Huguenots who settled along the Tar River in 1696 tell of meeting Tuscaroras with blond hair and blue eyes not long after their arrival. As Jamestown was the nearest English settlement, and they had no record of being attacked by Tuscarora, the likelihood that origin of those fair-skinned natives was the Lost Colony is high.[13]:28

In the late 1880s, North Carolina state legislator Hamilton McMillan discovered that his "redbones" (those of Indian blood) neighbors in Robeson County claimed to have been descended from the Roanoke settlers. He also noticed that many of the words in their language had striking similarities to obsolete English words. Furthermore, many of the family names were identical to those listed in Hakluyt's account of the colony. Thus on February 10, 1885, convinced that these were the descendants of the Lost Colony, he helped to pass the "Croatan bill", that officially designated the Native American population around Robeson county as Croatan.[15]:231–33 Two days later on February 12, 1885, the Fayetteville Observer published an article regarding the Robeson Native Americans' origins. This article states:

They say that their traditions say that the people we call the Croatan Indians (though they do not recognize that name as that of a tribe, but only a village, and that they were Tuscaroras), were always friendly to the whites; and finding them destitute and despairing of ever receiving aid from England, persuaded them to leave [Roanoke Island], and go to the mainland ... They gradually drifted away from their original seats, and at length settled in Robeson, about the center of the county ...[19]

However, the case was far from settled. A similar legend claims that the now extinct Saponi of Person County, North Carolina, are descended from the English colonists of Roanoke Island. Indeed, when these Native Americans were last encountered by subsequent settlers, they noted that these Native Americans already spoke English and were aware of the Christian religion. The historical surnames of this group also correspond with those who lived on Roanoke Island, and many exhibit European physical features along with Native American features. However, no documented evidence exists to link the Saponi to the Roanoke colonists.

Other tribes claiming partial descent from surviving Roanoke colonists include the Catawba (who absorbed the Shakori and Eno people), and the Coree and the Lumbee tribes.

Furthermore, Samuel A'Court Ashe was convinced that the colonists had relocated westward to the banks of the Chowan River in Bertie County, and Conway Whittle Sams claimed that after being attacked by Wanchese and Powhatan, the colonists scattered to multiple locations: the Chowan River, and south to the Pamlico and Neuse Rivers.[15]:233

Other theories

Chesepians

Historian David Beers Quinn hypothesized that the colony moved wholesale and was later destroyed. When Captain John Smith and the Jamestown colonists settled in Virginia in 1607, one of their assigned tasks was to locate the Roanoke colonists. The native leader Chief Powhatan told Captain Smith about his Virginia Peninsula-based Powhatan Confederacy, and went on to say that he had wiped out the Roanoke colonists just prior to the arrival of the Jamestown settlers because they were living with the Chesepian, a tribe living in the eastern portion of the present-day South Hampton Roads sub-region who, besides having refused to join Chief Powhatan's Powhatan Confederacy,[20]:21–24 were also prophesied to rise up and destroy his empire.[21]:101

Chief Powhatan reportedly produced several English-made iron implements to back his claim, but no bodies were found and no archaeological evidence has been found to support this claim,[22] however, and that which was found at a Chesepian village site in Great Neck Point in present-day Virginia Beach suggests that the Chesepian tribe was related to the Pamlico in Carolina, rather than the Powhatans. There were also reports of a Native American burial mound in the Pine Beach area of Sewell's Point in present day Norfolk, Virginia, where the principal Chesepian village of Skioak may have been located.

Spanish

Another theory is that the Spanish destroyed the colony. Earlier in the century, the Spanish did destroy evidence of the French colony of Fort Charles in coastal South Carolina and then massacred the inhabitants of Fort Caroline, a French colony near present-day Jacksonville, Florida. However, this is unlikely, as the Spanish were still looking for the location of England's failed colony as late as 1600, ten years after White discovered that the colony was missing.[3]:137

Dare Stones

From 1937 to 1941, a series of stones were discovered that were claimed to have been written by Eleanor Dare, mother of Virginia Dare. They told of the travelings of the colonists and their ultimate deaths. Most historians believe that they are a fraud, but there are some today that still believe the stones are genuine.[23]

Virginea Pars Map

In May 2011, Brent Lane of the First Colony Foundation was studying the Virginea Pars Map, which was made by John White during his 1585 visit to Roanoke Island, and noticed two patches where the map had been corrected. The patches are made of paper contemporaneous with that of the map. Lane asked researchers at the British Museum in London, where the map has been kept since 1866, what might be under the patches, sparking a research investigation. On May 3, 2012, at Wilson Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, members of the Foundation and representatives of the museum announced the discovery of "a large, square-shaped symbol with oddly shaped corners." This symbol, presumed to represent a fort, is visible when the map is viewed on a light box.[24] Some scholars speculate that the colonists relocated to that location, on what is now called Salmon Creek in the Bertie County community of Merry Hill. The Scotch Hall Preserve golf course community was planned on the site, but it has not been fully developed.[25]

The discovery of new information on the map led to more study of artifacts previously found, as well as additional digs in 2012 and 2014.[26]

Archaeological evidence

In 1998, East Carolina University organized "The Croatoan Project", an archaeological investigation into the events at Roanoke. The excavation team sent to the island uncovered a 10-carat (42%) gold 16th-century English signet ring, gun flints, and two copper farthings (produced sometime in the 1670s) at the site of the ancient Croatoan capital, 50 miles (80 km) from the old Roanoke colony. Genealogists were able to trace the lion crest on the signet ring to the Kendall coat of arms, and concluded that the ring most likely belonged to one Master Kendall who is recorded as having lived in the Ralph Lane colony on Roanoke Island from 1585 to 1586. If this is the case, the ring represents the first material connection between the Roanoke colonists and the Native Americans on Hatteras Island.[27][28][29]

It is also believed that the reason for the extreme deficiency in archaeological evidence is due to shoreline erosion. Since all that was found was a rustic looking fort on the north shore, and this location is well documented and backed up, it is believed that the settlement must have been nearby. The northern shore, between 1851 and 1970, lost 928 feet because of erosion. If in the years leading up to and following the brief life of the settlement at Roanoke, shoreline erosion was following the same trend, it is likely the site of dwellings is underwater, along with any artifacts or signs of life.[30]

Climate factors

In 1998, a team led by climatologist David W. Stahle, of the University of Arkansas, Department of Geography, in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and archaeologist Dennis B. Blanton, of the Center for Archaeological Research at The College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, used tree ring cores from 800-year-old bald cypresses taken from the Roanoke Island area of North Carolina and the Jamestown area of Virginia to reconstruct precipitation and temperature chronologies.

The researchers concluded that the settlers of the Lost Colony landed at Roanoke Island in the summer of the worst growing-season drought in 800 years. "This drought persisted for 3 years, from 1587 to 1589, and is the driest 3-year episode in the entire 800-year reconstruction," the team reported in the journal Science. A map shows that "the Lost Colony drought affected the entire southeastern United States but was particularly severe in the Tidewater region near Roanoke [Island]." The authors suggested that the Croatan who were shot and killed by the colonists may have been scavenging the abandoned village for food as a result of the drought.[31][32]

Portrayals and re-enactments

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paul Green wrote The Lost Colony in 1937 to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the birth of Virginia Dare. The play presents a conjecture of the fate of Roanoke Colony. It has played at Waterside Theater at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island nearly continually since, with the only interruption being during World War II. Alumni of the cast include Andy Griffith (who played Sir Walter Raleigh), William Ivey Long, Chris Elliott, Terrence Mann, and The Daily Show correspondent Dan Bakkedahl. Giles Milton's 2013 children's book, Children of the Wild, is a fictional recreation of the Roanoke colony, as seen through the perspective of four child colonists.

See also

- Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously

- Timeline of the colonization of North America

References

- ↑ "Charter to Sir Walter Raleigh March 25, 1584". University of Groningen. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Quinn, David B. (February 1985). Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies, 1584–1606. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4123-5. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Kupperman, Karen Ordahl (1984-01-25). Roanoke, The Abandoned Colony. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-7339-1. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ "Teacher Handbook to Roanoke Revisited". Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. National Park Service. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Milton, Giles (2001-10-19). Big Chief Elizabeth: The Adventures and Fate of the First English Colonists in America. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-42018-5. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Blacker, Irwin (1965). Hakluyt's Voyages: The Principle Navigations Voyages Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation. New York: The Viking Press. p. 522.

- ↑ Lane, Ralph. "The Account by Ralph Lane. An account of the particularities of the imployments of the English men left in Roanoke by Richard Greenevill under the charge of Master Ralph Lane Generall of the same, from the 17. of August 1585. until the 18. of June 1586. at which time they departed the Countrey; sent and directed to Sir Walter Ralegh.". Old South Leaflets (General Series) ; No. 119. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Fleming, Walter Lynwood (1909). The South in the Building of the Nation: History of the States. The Southern historical publication society. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Grizzard, Frank E.; Smith, D. Boyd (2007). Jamestown Colony: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-637-4. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Miller, Lee (2000). Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-584-4. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Neville, John D. "The John White Colony". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Harriot, Thomas. Nina Baym, ed. A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. The Norton Anthology of American Literature.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Smallwood, Arwin D. (2002-10-16). Bertie County: An Eastern Carolina History. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2395-8. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ Hunter, Douglas (2010-08-31). Half Moon: Henry Hudson and the Voyage That Redrew the Map of the New World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-1-60819-098-0. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Stick, David (November 1983). Roanoke Island, The Beginnings of English America. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4110-5. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ Warner, Charles Dudley, Captain John Smith, 1881. Repr. in Captain John Smith Project Gutenberg Text, accessed April 1, 2008.

- ↑ Lawson, John (1709). A New Voyage to Carolina. London. p. 48.

- ↑ Williams, Gwyn A. (1979). Madoc, The Making of a Myth. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-39450-7. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Croatan Indians of Robeson". Fayetteville Observer. February 12, 1885. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ↑ Parramore, Thomas C.; Stewart, Peter C.; Bogger, Tommy L. (April 2000). Norfolk: The First Four Centuries. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1988-1. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ Strachey, William (1612). The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia: Expressing the cosmographie and commodities of the country, togither with the manners and customes of the people. Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ McMullan, Jr., Philip S. "A Search for the Lost Colony in Beechland". The Lost Colony Center for Science and Research. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ↑ La Vere, David (July 2009). "The 1937 Chowan River ‘Dare Stone’: A Re-evaluation". North Carolina Historical Review.

- ↑ "Ancient Map Gives Clue to Fate of Lost Colony," The Daily Telegraph, telegraph.com, 4 May 2012, accessed 16 May 2012.

- ↑ Price, Jay (4 May 2012). "Old map offers new clues to fate of the Lost Colony". The Charlotte Observer.

- ↑ Waggoner, Martha (19 January 2015). "Researchers hopeful that NC site is that of Lost Colony". News & Observer. Associated Press.

- ↑ Family Crest on Sixteenth-Century Gold Ring Tentatively Identified

- ↑ Croatan Dig 1998–1999 Season at the Wayback Machine (archived May 2, 2000)

- ↑ "Guide to the Croatan 16".

- ↑ Dolan, Robert; Kenton Bosserman (September 1972). "Shoreline Erosion and the Lost Colony". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 62 (3): 424–426. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1972.tb00875.x.

- ↑ Stahle, David W. et al. (1998). "The Lost Colony and Jamestown Droughts". Science 280 (5363): 564–567. doi:10.1126/science.280.5363.564. PMID 9554842.

- ↑ Caroline Lee Heuer, Jonathon T. Overpeck. "Drought: A Paleo Perspective – Lost Colony and Jamestown Drought". Ncdc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

Further reading

- Hariot, Thomas, John White and John Lawson (1999). A Vocabulary of Roanoke. Evolution Publishing: Merchantville, NJ. ISBN 1-889758-81-7. This volume contains practically everything known about the Croatan language spoken on Roanoke Island.

- Miller, Lee, Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony Retrieved April 2011

- Giles Milton (2000). Big Chief Elizabeth. Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York. ISBN 0-374-26501-1. Critically acclaimed account, based on contemporary travel accounts from 1497–1611, of attempts to establish a colony in the Roanoke area. Milton is also the author of the 2013 children's fictional work, Children of the Wild, which tells the story of the colony through the eyes of four English children.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roanoke Colony. |

.svg.png)