Roald Dahl

| Roald Dahl | |

|---|---|

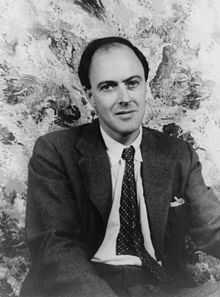

Dahl in 1954 | |

| Born |

13 September 1916 Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales |

| Died |

23 November 1990 (aged 74) Oxford, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, screenwriter |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1942–90 |

| Genre | Children's, adults' literature, horror, mystery, fantasy |

| Notable works | Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, Fantastic Mr Fox, Matilda, The Witches, The Twits, The BFG, The Gremlins, George's Marvellous Medicine, Danny, the Champion of the World, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More, My Uncle Oswald, Tales of the Unexpected |

| Spouse |

Patricia Neal (1953–83; divorced) Felicity Ann d'Abreu Crosland (1983–90; his death) |

| Children |

Olivia Twenty (1955–1962) Chantal Tessa Sophia (b. 1957) Theo Matthew (b. 1960); Ophelia Magdalena (b. 1964) Lucy Neal (b. 1965) |

| Relatives | Nicholas Logsdail (b. 1945, nephew) |

|

Military career | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

British Army (August–November 1939) |

| Years of service | 1939–1946 |

| Rank | Squadron Leader |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Website | |

|

roalddahl | |

Roald Dahl (/ˈroʊ.ɑːl ˈdɑːl/;[1] Norwegian: [ˈɾuːɑl dɑl]; 13 September 1916 – 23 November 1990) was a British novelist, short story writer, poet, screenwriter, and fighter pilot.

Born in Wales to Norwegian parents, Dahl served in the Royal Air Force during World War II, in which he became a flying ace and intelligence officer, rising to the rank of Acting wing commander. He rose to prominence in the 1940s with works for both children and adults and became one of the world's best-selling authors.[2][3] He has been referred to as "one of the greatest storytellers for children of the 20th century".[4] Among his awards for contribution to literature, he received the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement in 1983, and Children's Author of the Year from the British Book Awards in 1990. In 2008 The Times placed Dahl 16th on its list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[5]

Dahl's short stories are known for their unexpected endings and his children's books for their unsentimental, often very dark humour. His works include James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, My Uncle Oswald, The Witches, Fantastic Mr Fox, The Twits, Tales of the Unexpected, George's Marvellous Medicine, and The BFG.

Early life

Roald Dahl was born in 1916 at Villa Marie, Fairwater Road, in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales, to Norwegian parents, Harald Dahl and Sofie Magdalene Dahl (née Hesselberg).[6] Dahl's father had emigrated to the UK from Sarpsborg, Norway, and settled in Cardiff in the 1880s. His mother came over and married his father in 1911. Dahl was named after the polar explorer Roald Amundsen, a national hero in Norway at the time. He spoke Norwegian at home with his parents and his sisters Astri, Alfhild and Else. Dahl and his sisters were baptised at the Norwegian Church, Cardiff, where their parents worshipped.[7]

In 1920, when Dahl was three years old, his seven-year-old sister, Astri, died from appendicitis. Weeks later, his father died of pneumonia at the age of 57 while on a fishing trip in the Antarctic. With the option of returning to Norway to live with relatives, Dahl's mother decided to remain in Wales because Harald had wished to have their children educated in British schools, which he considered the world's best.[8]

Dahl first attended The Cathedral School, Llandaff. At the age of eight, he and four of his friends (one named Thwaites) were caned by the headmaster after putting a dead mouse in a jar of gobstoppers at the local sweet shop,[4] which was owned by a "mean and loathsome" old woman called Mrs Pratchett.[4] This was known among the five boys as the "Great Mouse Plot of 1924".[9] A favourite sweet among British schoolboys between the two World Wars, Dahl would later refer to gobstoppers in his literary creation, Everlasting Gobstopper.[10]

Thereafter, he transferred to a boarding school in England: St Peter's in Weston-super-Mare. Roald's parents had wanted him to be educated at an English public school and, because of a then regular ferry link across the Bristol Channel, this proved to be the nearest. His time at St Peter's was an unpleasant experience for him. He was very homesick and wrote to his mother every week but never revealed to her his unhappiness, being under the pressure of school censorship. Only after her death in 1967 did he find out that she had saved every single one of his letters, in small bundles held together with green tape.[11] Dahl wrote about his time at St Peter's in his autobiography Boy: Tales of Childhood.[12]

From 1929, he attended Repton School in Derbyshire, where, according to Boy: Tales of Childhood, a friend named Michael was viciously caned by headmaster Geoffrey Fisher, who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury and went on to crown Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. (However, according to Dahl's biographer Jeremy Treglown,[14] the caning took place in May 1933, a year after Fisher had left Repton and the headmaster concerned was in fact J. T. Christie, Fisher's successor.) This caused Dahl to "have doubts about religion and even about God".[15] He was never seen as a particularly talented writer in his school years, with one of his English teachers writing in his school report "I have never met anybody who so persistently writes words meaning the exact opposite of what is intended."[16]

Dahl was exceptionally tall, reaching 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m) in adult life.[17] He excelled at sports, being made captain of the school fives and squash teams, and also playing for the football team.[18] As well as having a passion for literature, he also developed an interest in photography[19] and often carried a camera with him. During his years at Repton, Cadbury, the chocolate company, would occasionally send boxes of new chocolates to the school to be tested by the pupils. Dahl would dream of inventing a new chocolate bar that would win the praise of Mr Cadbury himself; and this proved the inspiration for him to write his third children's book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964), and to include references to chocolate in other children's books.[20]

Throughout his childhood and adolescent years, Dahl spent the majority of his summer holidays with his mother's family in Norway, and wrote about many happy memories from those expeditions in Boy: Tales of Childhood, such as when he replaced the tobacco in his half–sister's fiancé's pipe with goat droppings.[21] He only experienced one unhappy memory of his holidays in Norway at around the age of eight, when his adenoids were removed by a doctor.[22] His childhood and first job selling kerosene in Midsomer Norton and surrounding villages in Somerset, South West England are subjects in Boy: Tales of Childhood.[23]

After finishing his schooling, in August 1934 Dahl crossed the Atlantic on the RMS Nova Scotia and hiked through Newfoundland with the Public Schools Exploring Society.[24][25] In July 1934, Dahl joined the Shell Petroleum Company. Following two years of training in the United Kingdom, he was transferred to first Mombasa, Kenya, then to Dar-es-Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania). Along with the only two other Shell employees in the entire territory, he lived in luxury in the Shell House outside Dar es Salaam, with a cook and personal servants. While out on assignments supplying oil to customers across Tanganyika, he encountered black mambas and lions, among other wildlife.[15]

Fighter ace

In August 1939, as World War II loomed, plans were made to round up the hundreds of Germans in Dar-es-Salaam. Dahl was made a lieutenant in the King's African Rifles, commanding a platoon of Askaris, indigenous troops serving in the colonial army.[26]

In November 1939, Dahl joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) as an aircraftman. After a 600-mile (970 km) car journey from Dar es Salaam to Nairobi, he was accepted for flight training with 16 other men, of whom only three others survived the war. With seven hours and 40 minutes experience in a De Havilland Tiger Moth, he flew solo;[27] Dahl enjoyed watching the wildlife of Kenya during his flights. He continued to advanced flying training in Iraq, at RAF Habbaniya, 50 miles (80 km) west of Baghdad. He was promoted to leading aircraftman on 24 August 1940.[28] Following six months' training on Hawker Harts, Dahl was made an acting pilot officer.

He was assigned to No. 80 Squadron RAF, flying obsolete Gloster Gladiators, the last biplane fighter aircraft used by the RAF. Dahl was surprised to find that he would not receive any specialised training in aerial combat, or in flying Gladiators. On 19 September 1940, Dahl was ordered to fly his Gladiator from Abu Sueir in Egypt, on to Amiriya to refuel, and again to Fouka in Libya for a second refuelling. From there he would fly to 80 Squadron's forward airstrip 30 miles (48 km) south of Mersa Matruh. On the final leg, he could not find the airstrip and, running low on fuel and with night approaching, he was forced to attempt a landing in the desert.[29] The undercarriage hit a boulder and the aircraft crashed, fracturing his skull, smashing his nose and temporarily blinding him.[30] He managed to drag himself away from the blazing wreckage and passed out. Later, he wrote about the crash in his first published work.[30]

Dahl was rescued and taken to a first-aid post in Mersa Matruh, where he regained consciousness, but not his sight, and was then taken by train to the Royal Navy hospital in Alexandria. There he fell in and out of love with a nurse, Mary Welland. An RAF inquiry into the crash revealed that the location to which he had been told to fly was completely wrong, and he had mistakenly been sent instead to the no man's land between the Allied and Italian forces.[31]

In February 1941, Dahl was discharged from hospital and passed fully fit for flying duties. By this time, 80 Squadron had been transferred to the Greek campaign and based at Eleusina, near Athens. The squadron was now equipped with Hawker Hurricanes. Dahl flew a replacement Hurricane across the Mediterranean Sea in April 1941, after seven hours flying Hurricanes. By this stage in the Greek campaign, the RAF had only 18 combat aircraft in Greece: 14 Hurricanes and four Bristol Blenheim light bombers. Dahl saw his first aerial combat on 15 April 1941, while flying alone over the city of Chalcis. He attacked six Junkers Ju-88s that were bombing ships and shot one down. On 16 April in another air battle, he shot down another Ju-88.[32]

On 20 April 1941, Dahl took part in the "Battle of Athens", alongside the highest-scoring British Commonwealth ace of World War II, Pat Pattle and Dahl's friend David Coke. Of 12 Hurricanes involved, five were shot down and four of their pilots killed, including Pattle. Greek observers on the ground counted 22 German aircraft downed, but because of the confusion of the aerial engagement, none of the pilots knew which aircraft they had shot down. Dahl described it as "an endless blur of enemy fighters whizzing towards me from every side".[33][34]

In May, as the Germans were pressing on Athens, Dahl was evacuated to Egypt. His squadron was reassembled in Haifa. From there, Dahl flew sorties every day for a period of four weeks, shooting down a Vichy French Air Force Potez 63 on 8 June and another Ju-88 on 15 June, but he then began to get severe headaches that caused him to black out. He was invalided home to Britain. Though at this time Dahl was only a Pilot Officer on probation, in September 1941 he was simultaneously confirmed as a Pilot Officer and promoted to war substantive Flying Officer.[35]

Diplomat, writer and intelligence officer

After being invalided home, Dahl was posted to an RAF training camp in Uxbridge while attempting to recover his health enough to become an instructor.[36] In late March 1942, while in London, he met the Under-Secretary of State for Air, Major Harold Balfour (later Lord Balfour), at his club. Impressed by his war record and conversational abilities, Balfour appointed Dahl as assistant air attaché at the British Embassy in Washington, D.C.. Initially resistant, he was finally persuaded by Balfour to accept, and took passage on the SS Batori from Glasgow a few days later. He arrived in Halifax on 14 April, after which he took a sleeper train to Montreal. Coming from war-starved Britain, Dahl was amazed by the wealth of food and amenities to be had in North America.[37] Arriving in Washington a week later, Dahl found he liked the atmosphere of the U.S. capital, but was unimpressed by his office in the British Air Mission, attached to the embassy. Nor was he impressed by the ambassador, Lord Halifax, whom he sometimes played tennis with and described as "a courtly English gentleman." As part of his duties as assistant air attaché, Dahl was to help neutralise the isolationist views many Americans still held by giving pro-British speeches and discussing his war service; the US had only entered the war the previous December, following the attack on Pearl Harbor. After only ten days in his new posting, Dahl strongly disliked it, feeling he had taken on "a most ungodly unimportant job."[38] As he later said:

| “ | I'd just come from the war. People were getting killed. I had been flying around, seeing horrible things. Now, almost instantly, I found myself in the middle of a pre-war cocktail party in America.[39] | ” |

However, at this time Dahl met the noted novelist C. S. Forester, who was also working to aid the British war effort. The Saturday Evening Post had asked Forester to write a story based on Dahl's flying experiences; Forester asked Dahl to write down some RAF anecdotes so that he could shape them into a story. After Forester read what Dahl had given him, he decided to publish the story exactly as Dahl had written it. The original title of the article was "A Piece of Cake" but the title was changed to "Shot Down Over Libya" to make it sound more dramatic, despite the fact that Dahl had not actually been shot down; it appeared in 1 August issue of the Post. He shared a house at 1610 34th Street, NW, in Georgetown, with another attaché. Dahl socialized with Texas publisher and oilman Charles E. Marsh at his house at 2136 R Street, NW, and the Marsh country estate in Virginia.[31][40]

Dahl was promoted to flight lieutenant (war-substantive) in August.[41] During the war, Forester worked for the British Information Service and was writing propaganda for the Allied cause, mainly for American consumption.[42] This work introduced Dahl to espionage and the activities of the Canadian spymaster William Stephenson, known by the codename "Intrepid".[43]

During the war, Dahl supplied intelligence from Washington to Stephenson and his organisation known as British Security Coordination,[40] which was part of MI6. He was revealed in the 1980s to have been serving to help promote Britain's interests and message in the United States and to combat the "America First" movement, working with such other well-known officers as Ian Fleming and David Ogilvy.[44] Dahl was once sent back to Britain by British Embassy officials, supposedly for misconduct – "I got booted out by the big boys," he said. Stephenson promptly sent him back to Washington—with a promotion to Wing Commander.[45] Towards the end of the war, Dahl wrote some of the history of the secret organisation and he and Stephenson remained friends for decades after the war.[46]

Upon the war's conclusion, Dahl held the rank of a temporary wing commander (substantive flight lieutenant). Owing to the seriousness of his accident in 1940, he was pronounced unfit for further service and was invalided out of the RAF in August 1946. He left the service with the substantive rank of squadron leader.[47] His record of five aerial victories, qualifying him as a flying ace, has been confirmed by post-war research and cross-referenced in Axis records, although it is most likely that he scored more than that during 20 April 1941 when 22 German aircraft were shot down.[48]

Post-war life

Dahl married American actress Patricia Neal on 2 July 1953 at Trinity Church in New York City. Their marriage lasted for 30 years and they had five children: Olivia Twenty (20 April 1955 – 17 November 1962); Chantal Tessa Sophia (born 1957); Theo Matthew (born 1960); Ophelia Magdalena (born 1964); and Lucy Neal (born 1965).[49]

On 5 December 1960, four-month-old Theo Dahl was severely injured when his baby carriage was struck by a taxicab in New York City. For a time, he suffered from hydrocephalus and, as a result, his father became involved in the development of what became known as the "Wade-Dahl-Till" (or WDT) valve, a device to alleviate the condition.[50][51]

In November 1962, Olivia Dahl died of measles encephalitis at age seven. Dahl subsequently became a proponent of immunisation and dedicated his 1982 book The BFG to his daughter.[52][53] When a children's book, Melanie's Marvelous Measles, was published in 2012 which claimed that catching measles was beneficial and vaccination was ineffective, a number of critics drew attention to the sad irony of the title's similarity with Dahl's George's Marvellous Medicine and the conflict with Dahl's experience.[54]

In 1965, Patricia Neal suffered three burst cerebral aneurysms while pregnant with their fifth child, Lucy; Dahl took control of her rehabilitation and she eventually re-learned to talk and walk, and even returned to her acting career,[55] an episode in their lives which was dramatised in the film The Patricia Neal Story, in which the couple were played by Glenda Jackson and Dirk Bogarde.[56]

.jpg)

Following a divorce from Neal in 1983, Dahl married Felicity "Liccy" Crosland at Brixton Town Hall, South London. Dahl and Crosland had previously been in a relationship.[57] According to biographer Donald Sturrock, Liccy gave up her job and moved into 'Gipsy House', Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire, which had been Dahl's home since 1954.[58]

In 1983 Dahl reviewed Tony Clifton's God Cried, a picture book about the 1982 Lebanon War that depicted Israelis killing thousands of Beirut inhabitants by bombing civilian targets.[59] Dahl's review stated that the book would make readers "violently anti-Israeli", writing, "I am not anti-Semitic. I am anti-Israel."[60] Dahl told a reporter in 1983, "There's a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity ... I mean there is always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere; even a stinker like Hitler didn't just pick on them for no reason."[60] Dahl maintained friendships with a number of Jews, including philosopher Isaiah Berlin, who said, "I thought he might say anything. Could have been pro-Arab or pro-Jew. There was no consistent line. He was a man who followed whims, which meant he would blow up in one direction, so to speak."[60]

In the 1986 New Years Honours List, Dahl was offered the Order of the British Empire (OBE), but turned it down, purportedly because he wanted a knighthood so that his wife would be Lady Dahl.[61][62] Dahl is the father of author Tessa Dahl and grandfather of author, cookbook writer and former model Sophie Dahl (after whom Sophie in The BFG is named).[63]

Death and legacy

Roald Dahl died on 23 November 1990, at the age of 74 of a blood disease, myelodysplastic syndrome, in Oxford,[64] and was buried in the cemetery at St Peter and St Paul's Church in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, England.[65] According to his granddaughter, the family gave him a "sort of Viking funeral". He was buried with his snooker cues, some very good burgundy, chocolates, HB pencils and a power saw. In his honour, the Roald Dahl Children's Gallery was opened in November 1996, at the Buckinghamshire County Museum in nearby Aylesbury.[66]

In 2002, one of Cardiff Bay's modern landmarks, the historic Oval Basin plaza, was re-christened "Roald Dahl Plass". "Plass" means "place" or "square" in Norwegian, referring to the acclaimed late writer's Norwegian roots. There have also been calls from the public for a permanent statue of him to be erected in the city.[67]

Dahl's charitable commitments in the fields of neurology, haematology and literacy have been continued by his widow since his death, through Roald Dahl's Marvellous Children's Charity, formerly known as the Roald Dahl Foundation.[68][69] In June 2005, the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre in the author's home village Great Missenden was officially opened by Cherie Blair, wife of UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, to celebrate the work of Roald Dahl and advance his work in literacy education.[65][70]

In 2008, the UK charity Booktrust and Children's Laureate Michael Rosen inaugurated The Roald Dahl Funny Prize, an annual award to authors of humorous children's fiction.[71][72] On 14 September 2009 (the day after what would have been Dahl's 93rd birthday) the first blue plaque in his honour was unveiled in Llandaff.[73] Rather than commemorating his place of birth, however, the plaque was erected on the wall of the former sweet shop (and site of "The Great Mouse Plot of 1924") that features in the first part of his autobiography Boy. It was unveiled by his widow Felicity and son Theo.[73] The anniversary of Dahl's birthday on 13 September is celebrated as "Roald Dahl Day" in Africa, the United Kingdom and Latin America.[74][75][76]

In honour of Roald Dahl, Gibraltar Post issued a set of four stamps in 2010 featuring Quentin Blake's original illustrations for four of the children's books written by Dahl during his long career; The BFG, The Twits, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Matilda.[77] A set of six stamps was issued by Royal Mail in 2012, featuring Quentin Blake's illustrations for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The Twits, The Witches, Matilda, Fantastic Mr Fox, James and the Giant Peach.[78] Dahl's influence has extended beyond literary figures, and he connected with film director Tim Burton with his "mixture of light and darkness, and not speaking down to kids, and the kind of politically incorrect humour that kids get".[79] Actress Scarlett Johansson named Fantastic Mr. Fox as one of the five books that made a difference to her.[80] Regarded as "one of the greatest storytellers for children of the 20th century",[4] Dahl was listed as one of the greatest British writers since 1945.[5] He ranks amongst the world's best-selling fiction authors with sales estimated at over 100 million,[2][3] and his books have been published in almost 50 languages.[74] In 2003, the UK survey entitled The Big Read carried out by the BBC in order to find the "nation's best loved novel" of all time, four of Dahl's books were named in the Top 100, with only works by Charles Dickens and Terry Pratchett featuring more.[81] In a 2006 list for the Royal Society of Literature, author J. K. Rowling named Charlie and the Chocolate Factory among her top ten books every child should read.[82]

Writing

Dahl's first published work, inspired by a meeting with C. S. Forester, was "A Piece of Cake" on 1 August 1942. The story, about his wartime adventures, was bought by The Saturday Evening Post for US$1000 (a substantial sum in 1942) and published under the title "Shot Down Over Libya".[83]

His first children's book was The Gremlins, published in 1943, about mischievous little creatures that were part of RAF folklore.[84] All the RAF pilots blamed the gremlins for all the problems with the aircraft. While at the British Embassy in Washington, Dahl sent a copy to the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt who read it to her grandchildren,[84] and the book was commissioned by Walt Disney for a film that was never made.[85] Dahl went on to create some of the best-loved children's stories of the 20th century, such as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, James and the Giant Peach, The Witches, Fantastic Mr Fox, The BFG, The Twits and George's Marvellous Medicine.[4]

Dahl also had a successful parallel career as the writer of macabre adult short stories, usually with a dark sense of humour and a surprise ending.[86] The Mystery Writers of America presented Dahl with three Edgar Awards for his work, and many were originally written for American magazines such as Collier's (The Collector's Item was Colliers Star Story of the week for 4 September 1948), Ladies Home Journal, Harper's, Playboy and The New Yorker. Works such as Kiss Kiss subsequently collected Dahl's stories into anthologies, gaining worldwide acclaim. Dahl wrote more than 60 short stories; they have appeared in numerous collections, some only being published in book form after his death (See List of Roald Dahl short stories). His three Edgar Awards were given for: in 1954, the collection Someone Like You; in 1959, the story "The Landlady"; and in 1980, the episode of Tales of the Unexpected based on "Skin".[86]

One of his more famous adult stories, "The Smoker" (also known as "Man from the South"), was filmed twice as both 1960 and 1985 episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and also adapted into Quentin Tarantino's segment of the 1995 film Four Rooms.[87] This oft-anthologised classic concerns a man in Jamaica who wagers with visitors in an attempt to claim the fingers from their hands. The 1960 Hitchcock version stars Steve McQueen and Peter Lorre.[87]

Dahl acquired a traditional Romanichal gypsy wagon in the 1960s, and the family used it as a playhouse for his children at home in Great Missenden. He later used the vardo as a writing room, where he wrote Danny, the Champion of the World in 1975.[88] Dahl incorporated a Gypsy wagon into the main plot of the book, where the young English boy, Danny, and his father, William (played by Jeremy Irons in the film adaptation) live in a Gypsy caravan.[89] Many local scenes and characters in Great Missenden inspired Dahl's stories.[65]

His short story collection Tales of the Unexpected was adapted to a successful TV series of the same name, beginning with "Man From the South".[90] When the stock of Dahl's own original stories was exhausted, the series continued by adapting stories by authors that were written in Dahl's style, including the writers John Collier and Stanley Ellin.[91]

Some of his short stories are supposed to be extracts from the diary of his (fictional) Uncle Oswald, a rich gentleman whose sexual exploits form the subject of these stories.[92] In his novel My Uncle Oswald, the uncle engages a temptress to seduce 20th century geniuses and royalty with a love potion secretly added to chocolate truffles made by Dahl's favourite chocolate shop, Prestat of Piccadilly, London.[92]

Memories with Food at Gipsy House, written with his wife Felicity and published posthumously in 1991, was a mixture of recipes, family reminiscences and Dahl's musings on favourite subjects such as chocolate, onions and claret.[68][93]

Children's fiction

"He [Dahl] was mischievous. A grown-up being mischievous. He addresses you, a child, as somebody who knows about the world. He was a grown-up – and he was bigger than most – who is on your side. That must have something to do with it."

Dahl's children's works are usually told from the point of view of a child. They typically involve adult villains who hate and mistreat children, and feature at least one "good" adult to counteract the villain(s).[4] These stock characters are possibly a reference to the abuse that Dahl stated that he experienced in the boarding schools he attended.[4] They usually contain a lot of black humour and grotesque scenarios, including gruesome violence. The Witches, George's Marvellous Medicine and Matilda are examples of this formula. The BFG follows it in a more analogous way with the good giant (the BFG or "Big Friendly Giant") representing the "good adult" archetype and the other giants being the "bad adults". This formula is also somewhat evident in Dahl's film script for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Class-conscious themes – ranging from the thinly veiled to the blatant – also surface in works such as Fantastic Mr Fox and Danny, the Champion of the World.

Dahl also features in his books characters who are very fat, usually children. Augustus Gloop, Bruce Bogtrotter and Bruno Jenkins are a few of these characters, although an enormous woman named Aunt Sponge is featured in James and the Giant Peach and the nasty farmer Boggis in Fantastic Mr Fox is an enormously fat character. All of these characters (with the possible exception of Bruce Bogtrotter) are either villains or simply unpleasant gluttons. They are usually punished for this: Augustus Gloop drinks from Willy Wonka's chocolate river, disregarding the adults who tell him not to, and falls in, getting sucked up a pipe and nearly being turned into fudge. In Matilda, Bruce Bogtrotter steals cake from the evil headmistress, Miss Trunchbull, and is forced to eat a gigantic chocolate cake in front of the school. Featuring in The Witches, Bruno Jenkins is turned into a mouse by witches who lure him to their convention with the promise of chocolate, and, it is speculated, possibly disowned or even killed by his parents because of this. Aunt Sponge is flattened by a giant peach. Dahl's mother used to tell him and his sisters tales about trolls and other mythical Norwegian creatures and some of his children's books contain references or elements inspired by these stories, such as the giants in The BFG, the fox family in Fantastic Mr Fox and the trolls in The Minpins.

In his poetry, Dahl gives a humorous re-interpretation of well-known nursery rhymes and fairy tales, providing surprise endings in place of the traditional happily-ever-after. Dahl's collection of poems Revolting Rhymes is recorded in audiobook form, and narrated by actor Alan Cumming.[94]

Screenplays

For a brief period in the 1960s, Dahl wrote screenplays. Two, the James Bond film You Only Live Twice and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, were adaptations of novels by Ian Fleming.[95] Dahl also began adapting his own novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which was completed and rewritten by David Seltzer after Dahl failed to meet deadlines, and produced as the film Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971). Dahl later disowned the film, saying he was "disappointed" because "he thought it placed too much emphasis on Willy Wonka and not enough on Charlie".[96] He was also "infuriated" by the deviations in the plot devised by David Seltzer in his draft of the screenplay. This resulted in his refusal for any more versions of the book to be made in his lifetime, as well as an adaption for the sequel Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator.[97]

Influences

A major part of Dahl's literary influences stemmed from his childhood. In his younger days, he was an avid reader, especially awed by fantastic tales of heroism and triumph. Amongst his favourite authors were Rudyard Kipling, William Makepeace Thackeray, Frederick Marryat and Charles Dickens, and their works went on to make a lasting mark on his life and writing.[98] Dahl was also a huge fan of ghost stories and claimed that Trolls by Jonas Lie was one of the finest ghost stories ever written. While he was still a youngster, his mother, Sofie Dahl, would relate traditional Norwegian myths and legends from her native homeland to Dahl and his sisters. Dahl always maintained that his mother and her stories had a strong influence on his writing. In one interview, he mentioned: "She was a great teller of tales. Her memory was prodigious and nothing that ever happened to her in her life was forgotten."[99] When Dahl started writing and publishing his famous books for children, he created a grandmother character in The Witches and later stated that she was based directly on his own mother as a tribute.[100][101]

Television

In 1961, Dahl hosted and wrote for a science fiction and horror television anthology series called Way Out, which preceded the Twilight Zone series on the CBS network for 14 episodes from March to July.[102] One of the last dramatic network shows shot in New York City, the entire series is available for viewing at The Paley Center for Media in New York City and Los Angeles.[103] He also wrote for the satirical BBC comedy programme That Was the Week That Was which was hosted by David Frost.[104]

The British television series, Tales of the Unexpected, originally aired on ITV between 1979 and 1988.[105] The series was released to tie in with Dahl's short stories of the same name, which had introduced readers to many motifs that were common in his writing.[90] The series was an anthology of different tales, initially based on Dahl's short stories.[90] The stories were sometimes sinister, sometimes wryly comedic and usually had a twist ending. Dahl introduced on camera all the episodes of the first two series, which bore the full title Roald Dahl's Tales of the Unexpected.[106]

Publications

Children's stories

|

Adult fiction

See the alphabetical List of Roald Dahl short stories. See also Roald Dahl: Collected Stories for a complete, chronological listing. |

Non-fiction

Plays

|

Film scripts

Television

|

Radio serials

- The Price of Fear: William and Mary (1973)

References

- ↑ "Pronunciation of Roald Dahl: How to pronounce Roald Dahl". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Britain celebrates first Roald Dahl Day". TODAY.com. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

Dahl's books, many of them darkly comic and featuring villainous adult enemies of the child characters, have sold over 100 million copies.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Fans gather for Dahl celebration". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 "Once upon a time, there was a man who liked to make up stories ...". The Independent. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Philip Howard, "Dahl, Roald (1916–1990)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ↑ Colin Palfrey (2006) Cardiff Soul: An Underground Guide to the City

- ↑ Jill C. Wheeler (2006) Roald Dahl p.9. ABDO Publishing Company, 2006

- ↑ Michael D. Sharp (2006) Popular Contemporary Writers p.516. Marshall Cavendish, 2006

- ↑ John Ayto (2012). "The Diner's Dictionary: Word Origins of Food and Drink". p. 154. Oxford University Press

- ↑ "Roald Dahl's School Days". BBC Wales. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ Dahl, Roald (1984). Boy: Tales of Childhood. Puffin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-130305-5.

- ↑ "Blue plaque marks Dahl sweet shop". BBC. Retrieved 24 December 2014

- ↑ Jeremy Treglown, Roald Dahl: A Biography (1994) , Faber and Faber, page 21. Treglown's source note is as follows: "Several people who were at the top of Priory House at the time have discussed it with me, particularly B.L.L. Reuss and John Bradburn."

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dahl, Roald (1984). Boy: Tales of Childhood. Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl". Kirjasto.sci.fi. 23 November 1990. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Roald Dahl – Penguin UK Authors – Penguin UK

- ↑ Shavick, Andrea (1997) Roald Dahl: the champion storyteller p.12. Oxford University Press, 1997

- ↑ "Roald Dahl biography". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Roald Dahl (derivative work) and Quentin Blake (2005). Roald Dahl's Incredible Chocolate Box. ISBN 0-14-131959-3.

- ↑ Boy and Going Solo, p.128 – p.132

- ↑ Boy and Going Solo, p.68 – 71

- ↑ Dahl, Roald (1984) Boy: tales of childhood p.172. Puffin Books, 1984

- ↑ Sturrock, Donald (2010). Storyteller: The Authorised Biography of Roald Dahl. London: HarperPress. pp. 93–94. ISBN 0007254768.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl (British author)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Donald Sturrock Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl p.116. Simon and Schuster, 2010

- ↑ Sturrock (2010: 120)

- ↑ "The London Gazette, 8 October 1940". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl: the plane crash that gave birth to a writer". Telegraph.co.uk. 9 August 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Alan Warren (1988) Roald Dahl pp.12, 87. Starmont House, 1988

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Dahl, Roald (1986). Going Solo. Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ Andrew Thomas Hurricane Aces 1941–45 Osprey Publishing, 2003

- ↑ Roald Dahl Going Solo p.151. Scholastic, 1996

- ↑ Dahl, Roald. Going Solo (excerpt).

- ↑ "Viewing Page 5664 of Issue 35292". London-gazette.co.uk. 30 September 1941. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Sturrock (2010: 163)

- ↑ Sturrock (2010: 163–165)

- ↑ Sturrock (2010: 166–167)

- ↑ Sturrock (2010: 167)

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Dietsch, Deborah K. (1 December 2013). "Roald Dahl Slept Here: From attaché to author". Washington Post Magazine. p. 10. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ "Viewing Page 5037 of Issue 35791". London-gazette.co.uk. 17 November 1942. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Cambridge Guide to Literature (Cambridge University Press, 1989) ISBN 0-521-26751-X.

- ↑ Ellen Schoeck I was there: a century of alumni stories about the University of Alberta, 1906–2006 University of Alberta, 2006

- ↑ The book "The Irregulars" (by Jennet Conant, Simon and Schuster 2008) describes this era of Dahl's life and those with whom he worked.

- ↑ Bill Macdonald – The True Intrepid p249 (Raincoast 2001)ISBN 1-55192-418-8 Dahl also speaks about his espionage work in the documentary The True Intrepid

- ↑ Macdonald – The True Intrepid p243 ISBN 1-55192-418-8.

- ↑ "The London Gazette". The London Gazette. 9 August 1946. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Christopher Shores and Clive Williams – Aces High: A Tribute to the Most Notable Fighter Pilots of the British and Commonwealth Air Forces in WWII (Grub Street Publishing, 1994) ISBN 1-898697-00-0.

- ↑ "'Dad also needed happy dreams': Roald Dahl, his daughters and the BFG". Telegraph.co.uk. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Water on the Brain". MedGadget: Internet Journal of Emerging Medical Technologies. 15 July 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- ↑ Dr Andrew Larner. "Tales of the Unexpected: Roald Dahl's Neurological Contributions" (PDF). Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation.

- ↑ Singh, Anita (7 August 2010) Roald Dahl's secret notebook reveals heartbreak over daughter's death The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ↑ Gonzalez, Robbie. "Read Roald Dahl's Powerful Pro-Vaccination Letter". Gawker Media. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Burnett, Dean (4 January 2013). "When preschool entertainment and vaccination controversy collide". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Barry Farrell (1969). Pat and Roald. Kingsport Press.

- ↑ David Thomson. "Patricia Neal: a beauty that cut like a knife". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl Official website". Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ Lynn F. Pearson Discovering Famous Graves Osprey Publishing, 2008

- ↑ Clifton, Tony (1983). "God Cried". Quartet Books, 1983

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Roald Dahl: A biography, Jeremy Treglown (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1994), pp. 255–256.

- ↑ "Queen's honours refused". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Roald Dahl among hundreds who turned down Queen's honours, Walesonline (also published in the Western Mail), 27 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Martin Chilton (18 November 2010) The 25 best children's books The Daily Telegraph

- ↑ "Deaths England and Wales 1984–2006". Findmypast.com. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 David Hurst (20 June 2005) "Roald Dahl's fantasy factory". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 3 June 2012

- ↑ Sharron L. McElmeel (1999)100 most popular children's authors: biographical sketches and bibliographies Libraries Unlimited, 1999

- ↑ "Roald Dahl and the Chinese chip shop". walesonline. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Sally Williams (12 September 2006) A plateful of Dahl The Telegraph'.' Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl's Marvellous Children's Charity". Marvellouschildrenscharity.org. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Clarie Heald (11 June 2005) Chocolate doors thrown open to Dahl BBC News

- ↑ "David Walliams up for Roald Dahl award". BBC News. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "The Roald Dahl Funny Prize". http://www.booktrust.org.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "South East Wales | Blue plaque marks Dahl sweet shop". BBC News. 14 September 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

Exhibitions and children's reading campaigns are being held to commemorate the life of Dahl, who died in 1990 and has sold more than 100 million books

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Alison Flood. "Roald Dahl Day expands into full month of special treats". the Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl Day celebrations". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Roald Dahl's 90th Birthday!, Random House UK. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ ""UK world's best selling children author on Gibraltar stamps" ''World Stamp News''". Worldstampnews.com. 15 May 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (9 January 2012). "Roald Dahl stamps honour classic children's author". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

Quentin Blake's famous illustrations of The Twits, Matilda and Fantastic Mr Fox all feature on a new series of stamps from the Royal Mail, issued to celebrate the work of Roald Dahl. Out from tomorrow, the stamps also show James and the Giant Peach and The Witches, while a triumphant Charlie Bucket from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is brandishing a golden ticket on the new first class stamp.

- ↑ Tim Burton, Mark Salisbury, Johnny Depp (2008). "Burton on Burton". p.223. Macmillan, 2006

- ↑ "Books That Made a Difference to Scarlett Johansson". Oprah.com. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "BBC – The Big Read – Top 100 Books". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Charlotte Higgins. "From Beatrix Potter to Ulysses ... what the top writers say every child should read". the Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Frances E. Ruffin Meet Roald Dahl The Rosen Publishing Group, 2006

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Donald, Graeme Sticklers, Sideburns & Bikinis: The Military Origins of Everyday Words and Phrases. Osprey Publishing, 2008

- ↑ Nick Tanner. "Dahl's Gremlins fly again, thanks to historian's campaign". the Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Andrew Maunder The Facts On File companion to the British short story. Infobase Publishing, 2007

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 James Mottram The Sundance kids: how the mavericks took back Hollywood Macmillan, 2006

- ↑ "English Gypsy caravan, Gypsy Wagon, Gypsy Waggon and Vardo: Photograph Gallery 1". Gypsywaggons.co.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Dahl, Roald (1975). "Danny, The Champion Of The World". p.13. Random House, 2010

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 The Facts on File companion to the British short story. p. 417. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Tales of the Unexpected (1979–88)". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Darrell Schweitzer (1985) Discovering modern horror fiction, Volume 2. Wildside Press LLC, 1985

- ↑ Books magazine, Volumes 5–7. Publishing News Ltd. 1991. p. 35. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ AV guide, Volumes 77–82. Scranton Gillette Communications. 1998. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl Day: my glimpse into the great writer's imagination". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2014

- ↑ Liz Buckingham, trustee for the Roald Dahl Museum, quoted in Tom Bishop: "Willy Wonka's Everlasting Film Plot", BBC News, July 2005

- ↑ Tom Bishop (July 2005) Willy Wonka's Everlasting Film Plot BBC News

- ↑ Rennay Craats (2003). "Roald Dahl". p. 1957. Weigl, 2003

- ↑ "Roald Dahl: young tales of the unexpected". Telegraph.co.uk. 30 August 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Roald Dahl". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mother: Sofie Dahl {influence upon} Roald Dahl". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "Way Out (TV Series 1961)". IMDb. 8 January 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "The Paley Center for Media: Way Out". The Paley Center for Media. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ McCann 2006, p.156

- ↑ "BFI: Film and TV Database – Tales of the Unexpected". BFI. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Vincent Terrace (1985) Encyclopedia of Television Series, Pilots and Specials: 1974–1984

- ↑ "Bibliography: The Complete Adventures of Charlie and Mr. Willy Wonka". Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ Source: written for a leaflet published c.1988 by Sandwell Health Authority (now Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust).

Further reading

- Philip Howard, "Dahl, Roald (1916–1990)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/39827 Retrieved 24 May 2006

- Donald Sturrock, Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl, Simon & Schuster, 2010. ISBN 978-1416550822 (See the link to excerpts in "External Links", below.)

- Jeremy Treglown, Roald Dahl: A Biography, Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1994. ISBN 978-0374251307

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roald Dahl. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Roald Dahl |

- Official website

- Roald Dahl's darkest hour (biography excerpt)

- Roald Dahl at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Roald Dahl at the Internet Movie Database

- Works by Roald Dahl at Open Library

- Radio interview with Dahl in Norwegian by NRK (1975)

- The Irregulars, Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington, 2008, New York Times Review, 17 October 2008.

- February 2011 profile of Patricia Neal on V.O.A.

- Footage of Roald Dahl judging at the Whitbread book prize in 1982

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

|