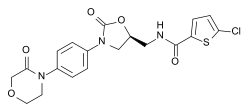

Rivaroxaban

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

|

(S)-5-chloro-N-{[2-oxo-3-[4-(3-oxomorpholin-4-yl) phenyl]oxazolidin-5-yl]methyl} thiophene-2-carboxamide | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Xarelto |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| |

| |

| oral | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% to 100%; Cmax = 2 – 4 hours (10 mg oral)[1] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4 , CYP2J2 and CYP-independent mechanisms[1] |

| Half-life | 5 – 9 hours in healthy subjects aged 20 to 45[1][2] |

| Excretion | 2/3 metabolized in liver and 1/3 eliminated unchanged[1] |

| Identifiers | |

|

366789-02-8 | |

| B01AX06 | |

| PubChem | CID 6433119 |

| DrugBank |

DB06228 |

| ChemSpider |

8051086 |

| UNII |

9NDF7JZ4M3 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL198362 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C19H18ClN3O5S |

| 435.882 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939) is an oral anticoagulant invented and manufactured by Bayer; in a number of countries it is marketed as Xarelto.[1] In the United States, it is marketed by Janssen Pharmaceutica.[3] It is the first available orally active direct factor Xa inhibitor. Rivaroxaban is well absorbed from the gut and maximum inhibition of factor Xa occurs four hours after a dose. The effects last approximately 8–12 hours, but factor Xa activity does not return to normal within 24 hours so once-daily dosing is possible.

Medical uses

In those with non-valvular atrial fibrillation it appears to be as good as warfarin in preventing nonhemorrhagic strokes and embolic events.[4] Rivaroxaban is associated with lower rates of serious and fatal bleeding events than warfarin though rivaroxaban is associated with higher rates of bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract.[5]

In September 2008, Health Canada granted marketing authorization for rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in people who have undergone elective total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery.[6]

In September 2008, the European Commission granted marketing authorization of rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults undergoing elective hip and knee replacement surgery.[7]

On July 1, 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rivaroxaban for prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which may lead to pulmonary embolism (PE), in adults undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery.[3]

On November 4, 2011, the U.S. FDA approved rivaroxaban for stroke prophylaxis in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

Adverse effects

The most serious adverse effect is severe internal bleeding.[8][9][10]

Mechanism of action

Rivaroxaban is an oxazolidinone derivative optimized for inhibiting both free Factor Xa and Factor Xa bound in the prothrombinase complex.[11] It is a highly selective direct Factor Xa inhibitor with oral bioavailability and rapid onset of action. Inhibition of Factor Xa interrupts the intrinsic and extrinsic pathway of the blood coagulation cascade, inhibiting both thrombin formation and development of thrombi. Rivaroxaban does not inhibit thrombin (activated Factor II), and no effects on platelets have been demonstrated.[1]

Rivaroxaban has predictable pharmacokinetics across a wide spectrum of patients (age, gender, weight, race) and has a flat dose response across an eightfold dose range (5–40 mg).[12] Clinical trial data have shown that it allows predictable anticoagulation with no need for dose adjustments and routine coagulation monitoring.[1] However, these trials have excluded patients with liver disease and end-stage liver disease; therefore, the safety of rivaroxaban in these populations is unknown.

Clinical development

Four clinical studies with a total enrollment of over 12,000 patients have shown that oral rivaroxaban has non-inferior and possibly superior efficacy compared to 40 mg per day of the subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin in preventing VTE in adult patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement surgery. However, the risk of bleeding was greater in patients randomized to rivaroxaban (10 mg/day) rather than enoxaparin (40 mg/day) and one patient (out of > 6000) randomized to rivaroxaban died of liver toxicity. The four studies include RECORD1 and 2 (hip replacement) and RECORD3 and 4 (knee replacement).[13][14][15][16] The RECORD4 study concluded that rivaroxaban was significantly more effective in reducing the occurrence of venous blood clots following knee replacement surgery than enoxaparin.[17]

In addition, rivaroxaban has been studied in phase III clinical trials for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF or afib) (ROCKET-AF), prevention of VTE in hospitalized medically ill patients (MAGELLAN), treatment and secondary prevention of VTE (EINSTEIN), and secondary prevention of major cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (ATLAS ACS TIMI 51).[18][19][20][21][22][23] More than 8,000 patients have been enrolled in the rivaroxaban clinical development program overall.[24] The study has been completed and shows that taking rivaroxaban once daily for 35 days was associated with a reduction in the risk of venous thrombosis, compared with standard 10-day treatment with enoxaparin by subcutaneous injection, in acutely ill medical patients. However, bleeding rates were significantly increased with rivaroxaban.[25][26]

A study in December 2010 shows that rivaroxaban can be a single-drug approach to the short-term and continued treatment of venous thrombosis and can also improve the benefit-to-risk profile of anticoagulation. The study compared oral rivaroxaban alone (15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, followed by 20 mg once daily) with subcutaneous enoxaparin followed by a vitamin K antagonist (either warfarin or acenocoumarol) for 3, 6, or 12 months in patients with acute, symptomatic DVT. The study also carried out a double-blind, randomized, event-driven superiority study that compared rivaroxaban alone (20 mg once daily) with placebo for an additional 6 or 12 months in patients who had completed 6 to 12 months of treatment for venous thromboembolism.[27]

Rivaroxaban had noninferior efficacy with respect to the primary outcome (36 events [2.1%], vs. 51 events with enoxaparin–vitamin K antagonist [3.0%]; hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44 to 1.04; P<0.001). The principal safety outcome occurred in 8.1% of the patients in each group. In the continued-treatment study, which included 602 patients in the rivaroxaban group and 594 in the placebo group, rivaroxaban had strong efficacy (8 events [1.3%], vs. 42 with placebo [7.1%]; hazard ratio, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.39; P<0.001). Four patients in the rivaroxaban group had nonfatal major bleeding (0.7%), versus none in the placebo group (P=0.11).[27][28]

Chemistry

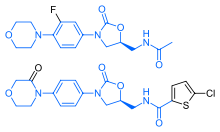

Rivaroxaban bears a striking structural similarity to the antibiotic linezolid: both drugs share the same oxazolidinone-derived core structure. Accordingly, rivaroxaban was studied for any possible antimicrobial effects and for the possibility of mitochondrial toxicity, which is a known complication of long-term linezolid use. Studies found that neither rivaroxaban nor its metabolites have any antibiotic effect against Gram-positive bacteria. As for mitochondrial toxicity, in vitro studies found the risk to be low.[29]

Related drugs

A number of anticoagulants inhibit the activity of Factor Xa. Unfractionated heparin (UFH), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and fondaparinux inhibit the activity of factor Xa indirectly by binding to circulating antithrombin (AT III). These agents must be injected. Warfarin, phenprocoumon, and acenocoumarol are orally active vitamin K antagonists (VKA) which decrease the liver's production of a number of coagulation factors, including Factor X. In recent years, a new series of oral, direct acting inhibitors of Factor Xa have entered clinical development. These include rivaroxaban, apixaban, betrixaban, LY517717, darexaban (YM150), and edoxaban (DU-176b).[30]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Xarelto: Summary of Product Characteristics". Bayer Schering Pharma AG. 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ Abdulsattar, Y; Bhambri, R; Nogid, A (May 2009). "Rivaroxaban (xarelto) for the prevention of thromboembolic disease: an inside look at the oral direct factor xa inhibitor.". P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management 34 (5): 238–44. PMID 19561868.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "FDA Approves XARELTO® (rivaroxaban tablets) to Help Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis in Patients Undergoing Knee or Hip Replacement Surgery" (Press release). Janssen Pharmaceutica. 2011-07-01. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ↑ Gómez-Outes, A; Terleira-Fernández, AI; Calvo-Rojas, G; Suárez-Gea, ML; Vargas-Castrillón, E (2013). "Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, or Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Subgroups.". Thrombosis 2013: 640723. PMID 24455237.

- ↑ Brown DG, Wilkerson EC, Love WE (March 2015). "A review of traditional and novel oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 72 (3): 524–34. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.027. PMID 25486915.

- ↑ "Bayer's Xarelto Approved in Canada" (Press release). Bayer. 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ "Bayer’s Novel Anticoagulant Xarelto now also Approved in the EU" (Press release). Bayer. 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ "Medication Guide--Xarelto" (PDF). http://www.fda.gov/''. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Xarelto Side Effects". http://www.webmd.com/''. WebMD. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Xarelto Side Effects Center". http://www.rxlist.com/''. RxList. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ Roehrig S, Straub A, Pohlmann J et al. (September 2005). "Discovery of the novel antithrombotic agent 5-chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3- [4-(3-oxomorpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}methyl)thiophene- 2-carboxamide (BAY 59-7939): an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 48 (19): 5900–8. doi:10.1021/jm050101d. PMID 16161994.

- ↑ Eriksson BI, Borris LC, Dahl OE et al. (November 2006). "A once-daily, oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939), for thromboprophylaxis after total hip replacement". Circulation 114 (22): 2374–81. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642074. PMID 17116766.

- ↑ Eriksson BI, Borris LC, Friedman RJ et al. (June 2008). "Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip arthroplasty". The New England Journal of Medicine 358 (26): 2765–75. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0800374. PMID 18579811.

- ↑ Kakkar AK, Brenner B, Dahl OE et al. (July 2008). "Extended duration rivaroxaban versus short-term enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial". Lancet 372 (9632): 31–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60880-6. PMID 18582928.

- ↑ Lassen MR, Ageno W, Borris LC et al. (June 2008). "Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty". The New England Journal of Medicine 358 (26): 2776–86. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa076016. PMID 18579812.

- ↑ Turpie A, Bauer K, Davidson B et al. "Comparison of rivaroxaban – an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor – and subcutaneous enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee replacement (RECORD4: a phase 3 study) / European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology Annual Meeting; May 29 – June 1, 2008; Nice, France, Abstract F85". Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume 92–B (SUPP II): 329.

- ↑ Turpie AG, Lassen MR, Davidson BL et al. (May 2009). "Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty (RECORD4): a randomised trial". Lancet 373 (9676): 1673–80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60734-0. PMID 19411100.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. "Randomized, Double-Blind Study Comparing Once Daily Oral Rivaroxaban With Adjusted-Dose Oral Warfarin for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. "MAGELLAN - Multicenter, Randomized, Parallel Group Efficacy Superiority Study in Hospitalized Medically Ill Patients Comparing Rivaroxaban with Enoxaparin". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. "Once-Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor Rivaroxaban in the Long-Term Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With Symptomatic Deep-Vein Thrombosis or Pulmonary Embolism. The Einstein-Extension Study". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. "Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor Rivaroxaban In Patients With Acute Symptomatic Deep-Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Without Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism: Einstein-DVT Evaluation". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. "Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor Rivaroxaban In Patients With Acute Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism (PE) With Or Without Symptomatic Deep-Vein Thrombosis: Einstein-PE Evaluation". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov. "A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Event-Driven Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Rivaroxaban in Subjects With a Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome". Retrieved 2009-02-11.

- ↑ "Venous Thromboembolic Event (VTE) Prophylaxis in Medically Ill Patients (MAGELLAN)". ClinicalTrials.gov. 11 March 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Hughes, Sue (5 April 2011). "MAGELLAN: Rivaroxaban prevents VTE in medical patients, but bleeding an issue". theheart.org. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ "About the MAGELLAN Study". Bayer HealthCare. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Bauersachs, M.D., Rupert; The EINSTEIN Investigators (December 23, 2010). "Oral Rivaroxaban for Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism". The New England Journal of Medecine 363 (26): 2499–2510. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1007903. PMID 21128814. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ "Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor Rivaroxaban In Patients With Acute Symptomatic Deep-Vein Thrombosis Without Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism: Einstein-DVT Evaluation". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (2008). "CHP Assessment Report for Xarelto (EMEA/543519/2008)" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ Turpie AG (January 2008). "New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation". European Heart Journal 29 (2): 155–65. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm575. PMID 18096568.

External links

- Rivaroxaban bound to proteins in the PDB

- Xarelto – Prescribing Information (European Union)

- Xarelto – Prescribing Information (United States)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||