Rigidity matroid

In the mathematics of structural rigidity, a rigidity matroid is a matroid that describes the number of degrees of freedom of an undirected graph with rigid edges of fixed lengths, embedded into Euclidean space. In a rigidity matroid for a graph with n vertices in d-dimensional space, a set of edges that defines a subgraph with k degrees of freedom has matroid rank dn − k. A set of edges is independent if and only if, for every edge in the set, removing the edge would increase the number of degrees of freedom of the remaining subgraph.[1][2][3]

Definition

A framework is an undirected graph, embedded into d-dimensional Euclidean space by providing a d-tuple of Cartesian coordinates for each vertex of the graph. From a framework with n vertices and m edges, one can define a matrix with m rows and nd columns, an expanded version of the incidence matrix of the graph called the rigidity matrix. In this matrix, the entry in row e and column (v,i) is zero if v is not an endpoint of edge e. If, on the other hand, edge e has vertices u and v as endpoints, then the value of the entry is the difference between the ith coordinates of v and u.[1][3]

The rigidity matroid of the given framework is a linear matroid that has as its elements the edges of the graph. A set of edges is independent, in the matroid, if it corresponds to a set of rows of the rigidity matrix that is linearly independent. A framework is called generic if the coordinates of its vertices are algebraically independent real numbers. Any two generic frameworks on the same graph G determine the same rigidity matroid, regardless of their specific coordinates. This is the (d-dimensional) rigidity matroid of G.[1][3]

Statics

A load on a framework is a system of forces on the vertices (represented as vectors). A stress is a special case of a load, in which equal and opposite forces are applied to the two endpoints of each edge (which may be imagined as a spring) and the forces formed in this way are added at each vertex. Every stress is an equilibrium load, a load that does not impose any translational force on the whole system (the sum of its force vectors is zero) nor any rotational force. A linear dependence among the rows of the rigidity matrix may be represented as a self-stress, a assignment of equal and opposite forces to the endpoints of each edge that is not identically zero but that adds to zero at every vertex. Thus, a set of edges forms an independent set in the rigidity matroid if and only if it has no self-stress.[3]

The vector space of all possible loads, on a system of n vertices, has dimension dn, among which the equilibrium loads form a subspace of dimension

. An independent set in the rigidity matroid has a system of equilibrium loads whose dimension equals the cardinality of the set, so the maximum rank that any set in the matroid can have is

. An independent set in the rigidity matroid has a system of equilibrium loads whose dimension equals the cardinality of the set, so the maximum rank that any set in the matroid can have is  . If a set has this rank, it follows that its set of stresses is the same as the space of equilibrium loads. Alternatively and equivalently, in this case every equilibrium load on the framework may be resolved by a stress that generates an equal and opposite set of forces, and the framework is said to be statically rigid.[3]

. If a set has this rank, it follows that its set of stresses is the same as the space of equilibrium loads. Alternatively and equivalently, in this case every equilibrium load on the framework may be resolved by a stress that generates an equal and opposite set of forces, and the framework is said to be statically rigid.[3]

Kinematics

If the vertices of a framework are in a motion, then that motion may be described over small scales of distance by its gradient, a vector for each vertex specifying its speed and direction. The gradient describes a linearized approximation to the actual motion of the points, in which each point moves at constant velocity in a straight line. The gradient may be described as a row vector that has one real number coordinate for each pair  where

where  is a vertex of the framework and

is a vertex of the framework and  is the index of one of the Cartesian coordinates of

is the index of one of the Cartesian coordinates of  -dimensional space; that is, the dimension of the gradient is the same as the width of the rigidity matrix.[1][3]

-dimensional space; that is, the dimension of the gradient is the same as the width of the rigidity matrix.[1][3]

If the edges of the framework are assumed to be rigid bars that can neither expand nor contract (but can freely rotate) then any motion respecting this rigidity must preserve the lengths of the edges: the derivative of length, as a function of the time over which the motion occurs, must remain zero. This condition may be expressed in linear algebra as a constraint that the gradient vector of the motion of the vertices must have zero inner product with the row of the rigidity matrix that represents the given edge. Thus, the family of gradients of (infinitesimally) rigid motions is given by the nullspace of the rigidity matrix.[1][3] For frameworks that are not in generic position, it is possible that some infinitesimally rigid motions (vectors in the nullspace of the rigidity matrix) are not the gradients of any continuous motion, but this cannot happen for generic frameworks.[2]

A rigid motion of the framework is a motion such that, at each point in time, the framework is congruent to its original configuration. Rigid motions include translations and rotations of Euclidean space; the gradients of rigid motions form a linear space having the translations and rotations as bases, of dimension  , which must always be a subspace of the nullspace of the rigidity matrix.

Because the nullspace always has at least this dimension, the rigidity matroid can have rank at most

, which must always be a subspace of the nullspace of the rigidity matrix.

Because the nullspace always has at least this dimension, the rigidity matroid can have rank at most  , and when it does have this rank the only motions that preserve the lengths of the edges of the framework are the rigid motions. In this case the framework is said to be first-order (or infinitesimally) rigid.[1][3] More generally, an edge

, and when it does have this rank the only motions that preserve the lengths of the edges of the framework are the rigid motions. In this case the framework is said to be first-order (or infinitesimally) rigid.[1][3] More generally, an edge  belongs to the matroid closure operation of a set

belongs to the matroid closure operation of a set  if and only if there does not exist a continuous motion of the framework that changes the length of

if and only if there does not exist a continuous motion of the framework that changes the length of  but leaves the lengths of the edges in

but leaves the lengths of the edges in  unchanged.[1]

unchanged.[1]

Although defined in different terms (column vectors versus row vectors, or forces versus motions) static rigidity and first-order rigidity reduce to the same properties of the underlying matrix and therefore coincide with each other. In two dimensions, the generic rigidity matroid also describes the number of degrees of freedom of a different kind of motion, in which each edge is constrained to stay parallel to its original position rather than being constrained to maintain the same length; however, the equivalence between rigidity and parallel motion breaks down in higher dimensions.[3]

Unique realization

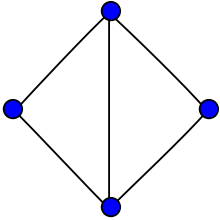

A framework has a unique realization in d-dimensional space if every placement of the same graph with the same edge lengths is congruent to it. Such a framework must necessarily be rigid, because otherwise there exists a continuous motion bringing it to a non-congruent placement with the same edge lengths, but unique realizability is stronger than rigidity. For instance, the diamond graph (two triangles sharing an edge) is rigid in two dimensions, but it is not uniquely realizable because it has two different realizations, one in which the triangles are on opposite sides of the shared edge and one in which they are both on the same side. Uniquely realizable graphs are important in applications that involve reconstruction of shapes from distances, such as triangulation in land surveying,[4] the determination of the positions of the nodes in a wireless sensor network,[5] and the reconstruction of conformations of molecules via nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.[4]

Bruce Hendrickson defined a graph to be redundantly rigid if it remains rigid after removing any one of its edges. In matroidal terms, this means that the rigidity matroid has the full rank  and that the matroid does not have any coloops. Hendrickson

proved that every uniquely realizable framework (with generic edge lengths) is either a complete graph or a

and that the matroid does not have any coloops. Hendrickson

proved that every uniquely realizable framework (with generic edge lengths) is either a complete graph or a  -vertex-connected, redundantly rigid graph, and he conjectured that this is an exact characterization of the uniquely realizable frameworks.[6] The conjecture is true for one and two dimensions; in the one-dimensional case, for instance, a graph is uniquely realizable if and only if it is connected and bridgeless.[7] However, Henrickson's conjecture is false for three or more dimensions.[8] For frameworks that are not generic, it is NP-hard to determine whether a given framework is uniquely realizable.[9]

-vertex-connected, redundantly rigid graph, and he conjectured that this is an exact characterization of the uniquely realizable frameworks.[6] The conjecture is true for one and two dimensions; in the one-dimensional case, for instance, a graph is uniquely realizable if and only if it is connected and bridgeless.[7] However, Henrickson's conjecture is false for three or more dimensions.[8] For frameworks that are not generic, it is NP-hard to determine whether a given framework is uniquely realizable.[9]

Relation to sparsity

Streinu & Theran (2008) define a graph as being  -sparse if every nonempty subgraph with

-sparse if every nonempty subgraph with  vertices has at most

vertices has at most  edges, and

edges, and  -tight if it is

-tight if it is  -sparse and has exactly

-sparse and has exactly  edges.[10] From the consideration of loads and stresses it can be seen that a set of edges that is independent in the rigidity matroid forms a

edges.[10] From the consideration of loads and stresses it can be seen that a set of edges that is independent in the rigidity matroid forms a  -sparse graph, for if not there would exist a subgraph whose number of edges would exceed the dimension of its space of equilibrium loads, from which it follows that it would have a self-stress.

By similar reasoning, a set of edges that is both independent and rigid forms a

-sparse graph, for if not there would exist a subgraph whose number of edges would exceed the dimension of its space of equilibrium loads, from which it follows that it would have a self-stress.

By similar reasoning, a set of edges that is both independent and rigid forms a  -tight graph. For instance, in one dimension, the independent sets form the edge sets of forests, (1,1)-sparse graphs, and the independent rigid sets form the edge sets of trees, (1,1)-tight graphs. In this case the rigidity matroid of a framework is the same as the graphic matroid of the corresponding graph.[2]

-tight graph. For instance, in one dimension, the independent sets form the edge sets of forests, (1,1)-sparse graphs, and the independent rigid sets form the edge sets of trees, (1,1)-tight graphs. In this case the rigidity matroid of a framework is the same as the graphic matroid of the corresponding graph.[2]

In two dimensions, Laman (1970) showed that the same characterization is true: the independent sets form the edge sets of (2,3)-sparse graphs and the independent rigid sets form the edge sets of (2,3)-tight graphs.[11] Based on this work the (2,3)-tight graphs (the graphs of minimally rigid generic frameworks in two dimensions) have come to be known as Laman graphs. The family of Laman graphs on a fixed set of  vertices forms the set of bases of the rigidity matroid of a complete graph, and more generally for every graph

vertices forms the set of bases of the rigidity matroid of a complete graph, and more generally for every graph  that forms a rigid framework in two dimensions, the spanning Laman subgraphs of

that forms a rigid framework in two dimensions, the spanning Laman subgraphs of  are the bases of the rigidity matroid of

are the bases of the rigidity matroid of  .

.

However, in higher dimensions not every  -tight graph is minimally rigid, and characterizing the minimally rigid graphs (the bases of the rigidity matroid of the complete graph) is an important open problem.[12]

-tight graph is minimally rigid, and characterizing the minimally rigid graphs (the bases of the rigidity matroid of the complete graph) is an important open problem.[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Graver, Jack E. (1991), "Rigidity matroids", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics 4 (3): 355–368, doi:10.1137/0404032, MR 1105942.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Whiteley, Walter (1992), "Matroids and rigid structures", Matroid Applications, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications 40, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 1–53, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511662041.002, MR 1165538.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Whiteley, Walter (1996), "Some matroids from discrete applied geometry", Matroid theory (Seattle, WA, 1995), Contemporary Mathematics 197, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. 171–311, doi:10.1090/conm/197/02540, MR 1411692.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hendrickson, Bruce (1995), "The molecule problem: exploiting structure in global optimization", SIAM Journal on Optimization 5 (4): 835–857, doi:10.1137/0805040, MR 1358807.

- ↑ Eren, T.; Goldenberg, O.K.; Whiteley, W.; Yang, Y.R.; Morse, A.S.; Anderson, B.D.O.; Belhumeur, P.N. (2004), "Rigidity, computation, and randomization in network localization", Proc. Twenty-third Annual Joint Conference of the IEEE Computer and Communications Societies (INFOCOM 2004) 4, pp. 2673–2684, doi:10.1109/INFCOM.2004.1354686.

- ↑ Hendrickson, Bruce (1992), "Conditions for unique graph realizations", SIAM Journal on Computing 21 (1): 65–84, doi:10.1137/0221008, MR 1148818.

- ↑ Jackson, Bill; Jordán, Tibor (2005), "Connected rigidity matroids and unique realizations of graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 94 (1): 1–29, doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2004.11.002, MR 2130278.

- ↑ Connelly, Robert (1991), "On generic global rigidity", Applied Geometry and Discrete Mathematics, DIMACS Series on Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science 4, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. 147–155, MR 1116345.

- ↑ Saxe, J. B. (1979), Embeddability of weighted graphs in k-space is strongly NP-hard, Technical Report, Pittsburgh, PA: Computer Science Department, Carnegie-Mellon University. As cited by Jackson & Jordán (2005).

- ↑ Streinu, I.; Theran, L. (2009), "Sparse hypergraphs and pebble game algorithms", European Journal of Combinatorics 30 (8): 1944–1964, arXiv:math/0703921, doi:10.1016/j.ejc.2008.12.018.

- ↑ Laman, G. (1970), "On graphs and the rigidity of plane skeletal structures", J. Engineering Mathematics 4 (4): 331–340, doi:10.1007/BF01534980, MR 0269535.

- ↑ Jackson, Bill; Jordán, Tibor (2006), "On the rank function of the 3-dimensional rigidity matroid", International Journal of Computational Geometry & Applications 16 (5-6): 415–429, doi:10.1142/S0218195906002117, MR 2269396.