Rigid category

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, a rigid category is a monoidal category where every object is rigid, that is, has a dual X* (the internal Hom [X, 1]) and a morphism 1 → X ⊗ X* satisfying natural conditions. The category is called right rigid or left rigid according to whether it has right duals or left duals. They were first defined (following Alexandre Grothendieck) by Neantro Saavedra-Rivano in his thesis on Tannakian categories.[1]

Definition

There are at least two equivalent definitions of a rigidity.

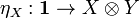

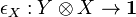

- An object X of a monoidal category is called left rigid if there is an object Y and morphisms

and

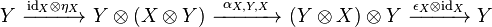

and  such that both compositions

such that both compositions

are identities. A right rigid object is defined similarly.

An inverse is an object X−1 such that both X ⊗ X−1 and X−1 ⊗ X are isomorphic to 1, the one object of the monoidal category. If an object X has a left (resp. right) inverse X−1 with respect to the tensor product then it is left (resp. right) rigid, and X* = X−1.

The operation of taking duals gives a contravariant functor on a rigid category.

Uses

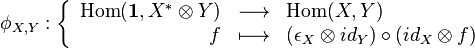

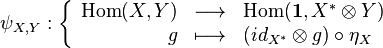

One important application of rigidity is in the definition of the trace of an endomorphism of a rigid object. The trace can be defined for any rigid category such that taking the ( )**, the functor of taking the dual twice repeated, is isomorphic to the identity functor. Then for any right rigid object X, and any other object Y, we may define the isomorphism

and its reciprocal isomorphism

.

.

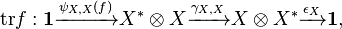

Then for any endomorphism  , the trace is of f is defined as the composition:

, the trace is of f is defined as the composition:

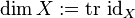

We may continue further and define the dimension of a rigid object to be:

.

.

Rigidity is also important because of its relation to internal Hom's. If X is a left rigid object, then every internal Hom of the form [X, Z] exists and is isomorphic to Z ⊗ Y. In particular, in a rigid category, all internal Hom's exist.

Alternative Terminology

A monoidal category where every object has a left (resp. right) dual is also sometimes called a left (resp. right) autonomous category. A monoidal category where every object has both a left and a right dual is sometimes called an autonomous category. An autonomous category that is also symmetric is called a compact closed category.

Discussion

A monoidal category is a category with a tensor product, precisely the sort of category for which rigidity makes sense.

- The category of pure motives is formed by rigidifying the category of effective pure motives.

Notes

- ↑

- N. Saavedra Rivano, Catégories Tannakiennes, Springer LNM 265, 1972

References

- Davydov, A. A. (1998). "Monoidal categories and functors". Journal of Mathematical Sciences 88 (4): 458–472. doi:10.1007/BF02365309.