Right and Left

| |

| Artist | Winslow Homer |

|---|---|

| Year | 1909 |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 71.8 cm × 122.9 cm (28.3 in × 48.4 in) |

| Location | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

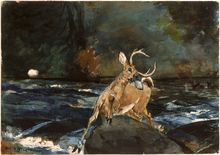

Right and Left is a 1909 oil on canvas painting by the American artist Winslow Homer. It depicts a pair of Common Goldeneye ducks at the moment they are hit by a hunter's shotgun blast as they attempt to take flight. Completed less than two years before his death, it was Homer's last great painting,[1] and has been the subject of a variety of interpretations regarding its origin, composition and meaning. As with his other late masterworks, it represents a return to the sporting and hunting subjects of Homer's earlier years, and was to be his final engagement with the theme. Its design recalls that of Japanese art, and the composition resembles that of a colored engraving by John James Audubon.

Background

In May 1908 Homer suffered temporary impairment of his speech and muscular control as the effects of a mild stroke; on June 4 he wrote his brother Charles that "I can paint as well as ever. I think my pictures better for having one eye in the pot and one eye up a chimney— a new departure in the art world."[2] By July 18 he was able to write that he had regained his abilities with the exception of tying "my neck tie in the way that I have done for the past 20 years....Every four or five days I try to do it but....it has been of no use."[3] Although he never completely recovered, Homer was well enough to attempt a major work, and it is probably Right and Left that he referred to in a letter to his brother Charles dated December 8, 1908: "I am painting when it is light enough on a most surprising picture".[4][5]

Homer's biographers offer varying accounts of the events surrounding both the painting's conception and initial development. Homer's first biographer, William Howe Downes, wrote that the ducks used for the painting had been purchased by the artist for his Thanksgiving dinner; he so admired their plumage that he painted them instead.[7] Homer's nephew told another of Homer's biographers, Philip Beam, that a friend of the artist named Phineas W. Sprague shot the birds in Prouts Neck that autumn and hung them on Homer's studio door, and the arrangement inspired the painting's design.[7] Given the Goldeneye's taste— Audubon called the duck "fishy, and in my opinion unfit for being eaten"— insofar as the implication is that the ducks were intended for food, neither story is altogether credible.[7]

Likewise there are different versions regarding Homer's preparatory methods. Downes recounted that Homer took to sea in a boat, accompanied by a man with a double-barreled shotgun, and studied the movements of birds as they were shot.[7] In Beam's telling, Homer stood atop a cliff at Prouts Neck while his neighbor Will Googins, fired blank charges in his direction from a rowboat offshore.[7] However, Homer was already familiar with this angle of shotgun blast, having in 1864 painted Defiance, a Civil War subject of a soldier being shot at, and in 1892 A Good Shot, Adirondacks, which shows the puff of distant rifle smoke and a mortally wounded deer hit in the foreground;[7] the latter especially anticipates the composition and intent of Right and Left.[6]

Painting

For its "restrained color and extraordinary composition" the painting's debt to Japanese art has been noted by art historians.[1][8][9] It has been compared to avian subjects by Okyo Maruyama, Hiroshige, and Hokusai, and was included in a major Japonisme exhibition in Paris in 1988.[9] As well, it resembles John James Audubon's plate Golden-Eye Duck.[1]

Against the tradition of birds painted as dead still life objects, Right and Left is unique for its depiction of the very moment of death.[10] Despite their rapid movement, the birds are seen as if frozen in a snapshot, and the viewer is literally afforded a bird's eye view, in the line of the hunter's fire.[10] Though the painting represents violent action, its formal aesthetic is that of sharply focused detachment,[10] and has been described by Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr. of the National Gallery of Art as "a staggeringly beautiful and almost oriental arrangement of birds--just abstract shapes against bands of the subtlest cream and grey".[11]

The design consists of four horizontal bands of sea and sky which are connected by a series of vertical and diagonal shapes formed by the ducks' bodies— the one at left (male) struggling to ascend, its partner in a similar position but turned 90 degrees, already falling limp— and wave crests.[12] Additionally, the birds' webbed feet and beaks and the boat's bow repeat the jagged contours of the waves.[12] Half hidden, the hunters occupy an ambiguous position, and it is uncertain whether the line above them denotes the horizon or a fog bank.[12] Atop this line is the rim of the sun, depicted as a red sliver.[12] At the right is a stray feather which "serves as an exclamation point for the whole composition."[12]

The painting was received by Knoedler & Co. gallery in New York by January 30, 1909, and was described by the gallery as The Golden Eye or Whistler Duck.[9] According to Downes the painting was initially exhibited without Homer's having titled it, and received its name from a hunter who shouted appreciatively "Right and left!", the term for a rifleman's accomplishment in taking down two birds in quick succession with a double-barreled shotgun.[7][13] Upon viewing the painting in New York, its first owner, Randal Morgan, asked several questions regarding Homer's intent: he inquired as to the direction of the largest wave, and the cause of the disturbance in the water at the front of the picture, which he believed was the impetus for the ducks' movement to leave their feeding.[9] The questions were forwarded to the artist, but his reply is unknown. On August 3, 1909 Morgan bought the painting for $5,000, $4,000 of which went to Homer.[9]

Meaning

Although it is a painting of a sporting subject, and thus was part of a popular anecdotal tradition, given both the violence of the subject and the fact that it was painted the year before Homer's death, Right and Left has invited metaphysical interpretation.[9][14] For art historian John Wilmerding, the painting embodied "a sense of the momentary and the universal, mortality illuminated by showing these creatures at the juncture of life and death".[9] It represents the summation of Homer's sporting pictures, and presents its subject with an "almost testamentary finality".[1]

It has also been suggested that in addition to summarizing interests that were lifelong for Homer, as well as referring to the works of previous artists, a modern and ironic meaning may have been intended as well: in 1908 air travel was a novel and transforming human achievement, one fraught with the adventure and danger of flight.[4] Considering his worldly and pictorial intelligence, it is possible that Homer intended Right and Left as an oblique reference to this aspect of modern life.[4]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Cikovsky, 374

- ↑ Cikovsky, 405

- ↑ Cooper, 238-239

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cikovsky, 375

- ↑ Cikovsky, 406

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cooper, 184

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Cikovsky, 388

- ↑ Gardner, 206

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Cikovsky, 389

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Lubbock

- ↑ National Gallery of Art

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Cooke, 118

- ↑ National Gallery of Art

- ↑ Cikovsky, 374-375

References

- Cikovsky, Jr., Nicolai; Kelly, Franklin. (1995). Winslow Homer. National Gallery of Art, Washington. ISBN 0-89468-217-2

- Cooke, Hereward Lester. Painting Techniques of the Masters. New York, Watson- Guptill, 1975. ISBN 0-8230-3863-7

- Cooper, Helen A. Winslow Homer Watercolors. National Gallery of Art, Washington: 1986. ISBN 0-300-03695-7

- Gardner, Albert Ten Eyck. Winslow Homer, American Artist: his World and his Work. Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., New York: 1961

- Homer, Winslow: Right and Left (1907). Lubbock, Tom, The Independent. 13 October 2006

External links

| ||||||||||