Richardson extrapolation

In numerical analysis, Richardson extrapolation is a sequence acceleration method, used to improve the rate of convergence of a sequence. It is named after Lewis Fry Richardson, who introduced the technique in the early 20th century.[1][2] In the words of Birkhoff and Rota, "... its usefulness for practical computations can hardly be overestimated."[3]

Practical applications of Richardson extrapolation include Romberg integration, which applies Richardson extrapolation to the trapezoid rule, and the Bulirsch–Stoer algorithm for solving ordinary differential equations.

Example of Richardson extrapolation

Suppose that we wish to approximate  , and we have a method

, and we have a method  that depends on a small parameter

that depends on a small parameter  , so that

, so that

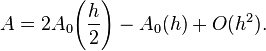

Define a new method

Then

is called the Richardson extrapolation of A(h), and has a higher-order

error estimate

is called the Richardson extrapolation of A(h), and has a higher-order

error estimate  compared to

compared to  .

.

Very often, it is much easier to obtain a given precision by using R(h) rather than A(h') with a much smaller h' , which can cause problems due to limited precision (rounding errors) and/or due to the increasing number of calculations needed (see examples below).

General formula

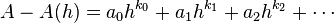

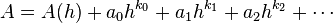

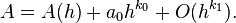

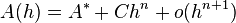

Let A(h) be an approximation of A that depends on a positive step size h with an error formula of the form

where the ai are unknown constants and the ki are known constants such that hki > hki+1.

The exact value sought can be given by

which can be simplified with Big O notation to be

Using the step sizes h and h / t for some t, the two formulas for A are:

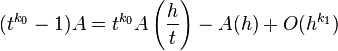

Multiplying the second equation by tk0 and subtracting the first equation gives

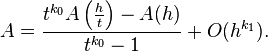

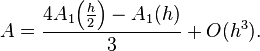

which can be solved for A to give

By this process, we have achieved a better approximation of A by subtracting the largest term in the error which was O(hk0). This process can be repeated to remove more error terms to get even better approximations.

A general recurrence relation can be defined for the approximations by

such that

with  .

.

The Richardson extrapolation can be considered as a linear sequence transformation.

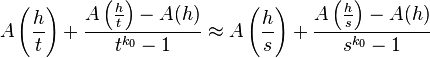

Additionally, the general formula can be used to estimate k0 when neither its value nor A is known a priori. Such a technique can be useful for quantifying an unknown rate of convergence. Given approximations of A from three distinct step sizes h, h / t, and h / s, the exact relationship

yields an approximate relationship

which can be solved numerically to estimate k0.

Example

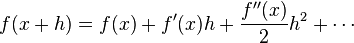

Using Taylor's theorem about h=0,

the derivative of f(x) is given by

If the initial approximations of the derivative are chosen to be

then ki = i+1.

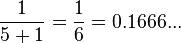

For t = 2, the first formula extrapolated for A would be

For the new approximation

we can extrapolate again to obtain

Example MATLAB code for Richardson extrapolation

The following demonstrates Richardson extrapolation to help solve the ODE  ,

,  with the Trapezoidal method. In this example we half the step size

with the Trapezoidal method. In this example we half the step size  each iteration and so in the discussion above we'd have that

each iteration and so in the discussion above we'd have that  . The error of the Trapezoidal method can be expressed in terms of odd powers so that the error over multiple steps can be expressed in even powers and so we take powers of

. The error of the Trapezoidal method can be expressed in terms of odd powers so that the error over multiple steps can be expressed in even powers and so we take powers of  in the pseudocode. We want to find the value of

in the pseudocode. We want to find the value of  , which has the exact solution of

, which has the exact solution of  since the exact solution of the ODE is

since the exact solution of the ODE is  . This pseudocode assumes that a function called

. This pseudocode assumes that a function called Trapezoidal(f, tStart, tEnd, h, y0) exists which performs the trapezoidal method on the function f, with starting point y0 and tStart, step size h, and attempts to computes y(tEnd)

Starting with too small an initial step size can potentially introduce error into the final solution. Although there are methods designed to help pick the best initial step size, one option is to start with a large step size and then to allow the Richardson extrapolation to reduce the step size each iteration until the error reaches the desired tolerance.

tStart = 0 %Starting time tEnd = 5 %Ending time f = -y^2 %The derivative of y, so y' = f(t, y(t)) = -y^2 % The solution to this ODE is y = 1/(1 + t) y0 = 1 %The initial position (i.e. y0 = y(tStart) = y(0) = 1) tolerance = 10^-11 %10 digit accuracy is desired maxRows = 20 %Don't allow the iteration to continue indefinitely initialH = tStart - tEnd %Pick an initial step size haveWeFoundSolution = false %Were we able to find the solution to the desired tolerance? not yet. h = initialH %Create a 2D matrix of size maxRows by maxRows to hold the Richardson extrapolates %Note that this will be a lower triangular matrix and that at most two rows are actually % needed at any time in the compuation. A = zeroMatrix(maxRows, maxRows) %Compute the top left element of the matrix A(1, 1) = Trapezoidal(f, tStart, tEnd, h, y0) %Each row of the matrix requires one call to Trapezoidal %This loops starts by filling the second row of the matrix, since the first row was computed above for i = 1 : maxRows - 1 %Starting at i = 1, iterate at most maxRows - 1 times h = h/2 %Half the previous value of h since this is the start of a new row %Call the Trapezoidal function with this new smaller step size A(i + 1, 1) = Trapezoidal(f, tStart, tEnd, h, y0) for j = 1 : i %Go across the row until the diagonal is reached %Use the last value computed (i.e. A(i + 1, j)) and the element from the % row above it (i.e. A(i, j)) to compute the next Richardson extrapolate A(i + 1, j + 1) = ((4^j).*A(i + 1, j) - A(i, j))/(4^j - 1); end %After leaving the above inner loop, the diagonal element of row i + 1 has been computed % This diagonal element is the last Richardson extrapolate to be computed %The difference between this extrapolate and the last extrapolate of row i is a good % indication of the error if(absoluteValue(A(i + 1, i + 1) - A(i, i)) < tolerance) %If the result is within tolerance print("y(5) = ", A(i + 1, i + 1)) %Display the result of the Richardson extrapolation haveWeFoundSolution = true break %Done, so leave the loop end end if(haveWeFoundSolution == false) %If we weren't able to find a solution to within the desired tolerance print("Warning: Not able to find solution to within the desired tolerance of ", tolerance); print("The last computed extrapolate was ", A(maxRows, maxRows)) end

See also

- Aitken's delta-squared process

- Takebe Kenko

- Richardson iteration

References

- ↑ Richardson, L. F. (1911). "The approximate arithmetical solution by finite differences of physical problems including differential equations, with an application to the stresses in a masonry dam". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 210 (459-470): 307–357. doi:10.1098/rsta.1911.0009.

- ↑ Richardson, L. F.; Gaunt, J. A. (1927). "The deferred approach to the limit". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 226 (636-646): 299–349. doi:10.1098/rsta.1927.0008.

- ↑ Page 126 of Birkhoff, Garrett; Gian-Carlo Rota (1978). Ordinary differential equations (3rd ed.). John Wiley and sons. ISBN 0-471-07411-X. OCLC 4379402.

- Extrapolation Methods. Theory and Practice by C. Brezinski and M. Redivo Zaglia, North-Holland, 1991.