Richard Wright (author)

| Richard Nathaniel Wright | |

|---|---|

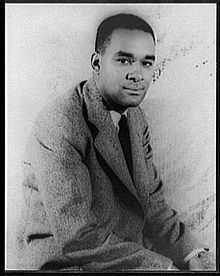

Wright in a 1939 photograph by Carl Van Vechten | |

| Born |

September 4, 1908 Plantation, Roxie, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died |

November 28, 1960 (aged 52) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, essayist, short story writer |

| Nationality | American, French |

| Genre | Drama, fiction, non-fiction, autobiography |

| Notable works | Uncle Tom's Children, Native Son, Black Boy, The Outsider |

Richard Nathaniel Wright (September 4, 1908 – November 28, 1960) was an American author of sometimes controversial novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction. Much of his literature concerns racial themes, especially those involving the plight of African Americans during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. Literary critics believe his work helped change race relations in the United States in the mid-20th century.[1]

Early life and education

Childhood in the South

Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908, at Rucker's Plantation, between Roxie and the larger town, Natchez, Mississippi.[2] His autobiography, Black Boy, covers the interval in his life from 1912 until May 1936.[3] Richard's father left the family when the boy was six years old, and he did not see him for another 25 years. After his single parent mother became incapacitated with a stroke, he was separated from his younger brother and lived briefly with his uncle. At that time, 12 years old, he had not yet had a single complete year of schooling. Soon Richard and his mother moved to the home of his maternal grandmother in Jackson, Mississippi, where he lived from early 1920 until late 1925. Finally he was able to go to school regularly, and after a year at age 13 entered the Jim Hill public school where he was shortly promoted to sixth grade, after only two weeks.[4] In his grandparent's household, he felt stifled by his aunt and grandmother, who tried to force him to pray that he might find God. He later threatened to leave home because his Grandmother Wilson refused to permit him to work on Saturdays, the Adventist Sabbath. This early strife with his aunt and grandmother left him with a permanent, uncompromising hostility toward religious solutions to everyday problems.

In 1923, Wright had excelled in grade school and then junior high school, and was made class valedictorian of Smith Robertson junior high school.[2] He was assigned to write a paper to be delivered at a public auditorium, at graduation. Later, he was called to the principal's office, and the principal gave him a prepared speech to present in place of his assignment. Richard challenged the principal, and said "...the people are coming to hear the students, and I won't make a speech that you've written".[5] The principal threatened him obliquely by suggesting Richard might not graduate if he persisted, despite having passed all the examinations, and then tried to entice Richard with an opportunity to become a teacher. Determined not to be called an Uncle Tom, Richard refused to deliver the principal's carefully prepared valedictory address that would not offend the white school officials. The principal put pressure on one of Richard's uncles to speak to the boy and get him to change his mind, but when his uncle tried to persuade Richard, he was adamant about delivering his speech, and refused to let his uncle edit it. Despite further pressure from his classmates, Richard delivered his speech as he had planned.

In September that year, Wright registered for mathematics, English, and history courses at the new Lanier High School in Jackson, but had to stop attending classes after a few weeks of irregular attendance because he needed to earn money for family expenses.[2] The next year, in his plan to become independent and call for his mother to live with him when he could support her, Wright moved on his own to Memphis, TN in November 1925. The following year, his mother and brother came to live with him, and the family was reunited. Shortly thereafter, Richard resolved to leave the Jim Crow life and go to Chicago.[6]

His childhood in Mississippi as well as in Memphis, TN, and Elaine, AR shaped his lasting impressions of American racism.[7] At the age of 15, while in eighth grade, Wright published his first story, "The Voodoo of Hell's Half-Acre", in the local Black newspaper Southern Register, but no extant copies survive.[2] He gave a brief description of the story about a villain who sought a widow's home in Chapter 7 of Black Boy ".[8]

Coming of Age in Chicago

Wright moved to Chicago in 1927. After securing employment as a postal clerk, he read other writers and studied their styles during his time off. When his job at the post office was eliminated, he was forced to go on relief in 1931. In 1932, he began attending meetings of the John Reed Club. As the club was dominated by the Communist Party, Wright established a relationship with a number of party members. Especially interested in the literary contacts made at the meetings, Wright formally joined the Communist Party in late 1933 and as a revolutionary poet who wrote numerous proletarian poems "We of the Red Leaves of Red Books", for example), for The New Masses and other left-wing periodicals. A power struggle within the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club led to the dissolution of the club's leadership; Wright was told he had the support of the club's party members if he was willing to join the party.[9]

By 1935, Wright had completed his first novel, Cesspool, published as Lawd Today (1963), and in January 1936 his story "Big Boy Leaves Home" was accepted for publication in New Caravan. In February, he began working with the National Negro Congress, and in April he chaired the South Side Writers Group, whose membership included Arna Bontemps and Margaret Walker. Wright submitted some of his critical essays and poetry to the group for criticism and read aloud some of his short stories. Through the club, he edited Left Front, a magazine that the Communist Party shut down in 1937, despite Wright's repeated protests.[10] Throughout this period, Wright also contributed to The New Masses magazine.

While he was at first pleased by positive relations with white Communists in Chicago, he was later humiliated in New York City by some who rescinded an offer to find housing for Wright because of his race.[11] Some black Communists denounced Wright as a bourgeois intellectual. However, he was largely autodidactic, having been forced to end his public education after the completion of grammar school.[12]

Wright's insistence that young communist writers be given space to cultivate their talents and his working relationship with a black nationalist communist led to a public falling out with the party and leading members. Wright described this episode with his fictional character of African-American communist Buddy Nealson.[13] Wright was threatened at knifepoint by fellow-traveler co workers, denounced as a Trotskyite in the street by strikers and physically assaulted by former comrades when he tried to join them during the 1936 May Day march.[14]

Career

In 1937, Richard Wright moved to New York, where he forged new ties with Communist Party members. He worked on the WPA Writers' Project guidebook to the city, New York Panorama (1938), and wrote the book's essay on Harlem. Wright became the Harlem editor of the Daily Worker. In the summer and fall he wrote over two hundred articles for the Daily Worker and helped edit a short-lived literary magazine New Challenge. The year was also a landmark for Wright because he met and developed a friendship with Ralph Ellison that would last for years, and he learned that he would receive the Story magazine first prize of five hundred dollars for his short story "Fire and Cloud".[15]

After Wright received the Story magazine prize in early 1938, he shelved his manuscript of Lawd Today and dismissed his literary agent, John Troustine. He hired Paul Reynolds, the well-known agent of Paul Laurence Dunbar, to represent him. Meanwhile, the Story Press offered Harper all of Wright's prize-entry stories for a book, and Harper agreed to publish them.

Wright gained national attention for the collection of four short stories entitled Uncle Tom's Children (1938). He based some stories on lynching in the Deep South. The publication and favorable reception of Uncle Tom's Children improved Wright's status with the Communist party and enabled him to establish a reasonable degree of financial stability. He was appointed to the editorial board of New Masses, and Granville Hicks, prominent literary critic and Communist sympathizer, introduced him at leftist teas in Boston. By May 6, 1938, excellent sales had provided Wright with enough money to move to Harlem, where he began writing the novel Native Son (1940).

The collection also earned him a Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to complete Native Son. It was selected by the Book of the Month Club as its first book by an African-American author. The lead character, Bigger Thomas, represented the limitations that society placed on African Americans as he could only gain his own agency and self-knowledge by committing heinous acts.

Wright was criticized for his works' concentration on violence. In the case of Native Son, people complained that he portrayed a black man in ways that seemed to confirm whites' worst fears. The period following publication of Native Son was a busy time for Wright. In July 1940 he went to Chicago to do research for a folk history of blacks to accompany photographs selected by Edwin Rosskam. While in Chicago he visited the American Negro Exhibition with Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps and Claude McKay.

He then went to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he and Paul Green collaborated on a dramatic version of Native Son. In January 1941 Wright received the prestigious Spingarn Medal for noteworthy achievement by a black. Native Son opened on Broadway, with Orson Welles as director, to generally favorable reviews in March 1941. A volume of photographs almost completely drawn from the files of the Farm Security Administration, with text by Wright, Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, was published in October 1941 to wide critical acclaim.

Wright's semi-autobiographical Black Boy (1945) described his early life from Roxie up until his move to Chicago at age 19, his clashes with his Seventh-day Adventist family, his troubles with white employers and social isolation. American Hunger, published posthumously in 1977, was originally intended as the second volume of Black Boy. The Library of America edition restored it to that form.

This book detailed Wright's involvement with the John Reed Clubs and the Communist Party, which he left in 1942. The book implied he left earlier, but his withdrawal was not made public until 1944. In the volumes' restored form, the diptych structure compares the certainties and intolerance of organized communism, the "bourgeois" books and condemned members, with similar qualities to fundamentalist organized religion. Wright disapproved of the purges in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, he continued to believe in far-left democratic solutions to political problems.

France

Wright moved to Paris in 1946, and became a permanent American expatriate.[16] In Paris, he became friends with Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. His Existentialist phase was depicted in his second novel, The Outsider (1953), which described an African-American character's involvement with the Communist Party in New York. He also was friends with fellow expatriate writers Chester Himes and James Baldwin, although the relationship with the latter ended in acrimony after Baldwin published his essay "Everybody's Protest Novel" (collected in Notes of a Native Son), in which he criticized Wright's stereotypical portrayal of Bigger Thomas. In 1954 he published a minor novel, Savage Holiday.

After becoming a French citizen in 1947, Wright continued to travel through Europe, Asia, and Africa. These experiences were the basis of numerous nonfiction works. In 1949, Wright contributed to the anti-communist anthology The God That Failed; his essay had been published in the Atlantic Monthly three years earlier and was derived from the unpublished portion of Black Boy. He was invited to join the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which he rejected, correctly suspecting that it had connections with the CIA. The CIA and FBI had Wright under surveillance starting in 1943. Wright was blacklisted by Hollywood movie studio executives in the 1950s, but, in 1950, starred as the teenager Bigger Thomas (Wright was 42) in an Argentinian film version of Native Son.

In mid-1953, Wright traveled to the Gold Coast, where Kwame Nkrumah was leading the country to independence from British rule. Before Wright returned to Paris, he gave a confidential report to the United States consulate in Accra on some of the things he had learned about Nkrumah and his political party. After Wright returned to Paris he met twice with an officer from the U.S. Department of State. The officer's report includes what Wright had learned from Nkrumah adviser George Padmore about Nkrumah's plans for the Gold Coast after its independence (as Ghana). Padmore, a Trinidadian living in London, believed Wright to be a good friend, as his many letters in the Wright papers at Yale's Beinecke Library attest, and their correspondence continued. Wright's book on his journey, Black Power, was published in 1954; its London publisher was Padmore's, Dennis Dobson.[17]

In addition to whatever political motivations Wright had for reporting to American officials, he was in the uncomfortable position of an American who did not want to go back to the United States and needed to have his passport renewed. According to Wright biographer Addison Gayle, just a few months later Wright answered questions at the American embassy in Paris about people he had met in the Communist Party who were at this point being prosecuted under the Smith Act.[18]

Exploring the reasons Wright appeared to have little to say about the civil rights movement unfolding in the United States in the 1950s, historian Carol Polsgrove has gathered evidence of what his fellow writer Chester Himes called the "extraordinary pressure" Wright was under not to write about the American scene. Even Ebony magazine delayed publishing his essay "I Choose Exile" until he suggested it would be better to publish it in a white periodical, "since a white periodical would be less vulnerable to accusations of disloyalty". He thought the Atlantic Monthly was interested, but in the end, the piece went unpublished.[19]

In 1955, Wright visited Indonesia for the Bandung Conference. He recorded his observations on the conference as well as on Indonesian cultural conditions in The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Wright was upbeat about the conference, enthusiastic about possibilities posed by this meeting among recently colonial nations. He gave at least two lectures to Indonesian cultural groups including PEN Club Indonesia, and he spent time interviewing Indonesian artists and intellectuals in preparation to write The Color Curtain.[20] Several Indonesian artists and intellectuals that Wright met later offered commentary on the way Wright depicted Indonesian cultural conditions in his travel writing.[21]

Other works by Richard Wright included White Man, Listen! (1957); a novel The Long Dream in 1958, which was dramatized in New York in 1960 by Ketti Frings and which explores the relationship between a man named Fish and his father;[22] as well as a collection of short stories, Eight Men, published in 1961, shortly after his death. His works primarily dealt with the poverty, anger, and protests of northern and southern urban black Americans.

His agent, Paul Reynolds, sent overwhelmingly negative criticism of Wright's 400-page "Island of Hallucinations" manuscript in February 1959. Despite that, in March Wright outlined a novel in which Fish was to be liberated from his racial conditioning and become a dominating character. By May 1959, Wright wanted to leave Paris and live in London. He felt French politics had become increasingly submissive to American pressure. The peaceful Parisian atmosphere he had enjoyed had been shattered by quarrels and attacks instigated by enemies of the expatriate black writers.

On June 26, 1959, after a party marking the French publication of White Man, Listen! Wright became ill, victim of a virulent attack of amoebic dysentery probably contracted during his stay on the Gold Coast. By November 1959 his wife had found a London apartment, but Wright's illness and "four hassles in twelve days" with British immigration officials ended his desire to live in England.

On February 19, 1960, Wright learned from Reynolds that the New York premiere of the stage adaptation of The Long Dream received such bad reviews that the adapter, Ketti Frings, had decided to cancel further performances. Meanwhile, Wright was running into additional problems trying to get The Long Dream published in France. These setbacks prevented his finishing revisions of Island of Hallucinations, for which he needed to get a commitment from Doubleday.

In June 1960, Wright recorded a series of discussions for French radio dealing primarily with his books and literary career. He also covered the racial situation in the United States and the world, and specifically denounced American policy in Africa. In late September, to cover extra expenses for his daughter Julia's move from London to Paris to attend the Sorbonne, Wright wrote blurbs for record jackets for Nicole Barclay, director of the largest record company in Paris.

In spite of his financial straits, Wright refused to compromise his principles. He declined to participate in a series of programs for Canadian radio because he suspected American control. For the same reason, he rejected an invitation from the Congress for Cultural Freedom to go to India to speak at a conference in memory of Leo Tolstoy. Still interested in literature, Wright helped Kyle Onstott get Mandingo (1957) published in France.

Wright's last display of explosive energy occurred on November 8, 1960, in his polemical lecture, "The Situation of the Black Artist and Intellectual in the United States", delivered to students and members of the American Church in Paris. He argued that American society reduced the most militant members of the black community to slaves whenever they wanted to question the racial status quo. He offered as proof the subversive attacks of the Communists against Native Son and the quarrels which James Baldwin and other authors sought with him. On November 26, 1960, Wright talked enthusiastically about Daddy Goodness with Langston Hughes and gave him the manuscript.

Wright had contracted amoebic dysentery on a visit to Africa in 1957, and despite various treatments, his health deteriorated over the next three years.[23] He died in Paris on November 28, 1960, of a heart attack at the age of 52. He was interred in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery. However, Wright's daughter Julia claimed that her father was murdered.[24]

A number of Wright's works have been published posthumously. Some of Wright's more shocking passages dealing with race, sex, and politics were cut or omitted before original publication. In 1991, unexpurgated versions of Native Son, Black Boy, and his other works were published. In addition, in 1994, his novella Rite of Passage was published for the first time.[25]

In the last years of his life, Wright became enamored with the haiku and wrote over 4,000 such poems. In 1998 a book was published (Haiku: This Other World) with 817 of his own favorite haikus. Many of these haikus still maintain an uplifting quality even as they deal with coming to terms with loneliness, death, and the forces of nature.

A collection of Wright's travel writings was published by Mississippi University Press in 2001. At his death, Wright left an unfinished book, A Father's Law,[26] dealing with a black policeman and the son he suspects of murder. Julia Wright published A Father's Law in January 2008. An omnibus edition containing Wright's political works was published under the title Three Books from Exile: Black Power; The Color Curtain; and White Man, Listen!

Personal life

In August 1939, with Ralph Ellison as best man,[27] Wright married Dhimah Rose Meidman,[28] a modern-dance teacher of Russian Jewish ancestry, but the marriage ended a year later, and on March 12, 1941, he married Ellen Poplar née Poplowitz,[29][30] a Communist organizer from Brooklyn.[31] They had two daughters: Julia born in 1942 and Rachel in 1949.[32] Ellen Wright, who died on April 6, 2004, aged 92, was the executrix of the Richard Wright Estate, as well as being a literary agent in her own right (as Julia Wright has noted), numbering among her clients Simone de Beauvoir, Eldridge Cleaver, Violette Leduc, and others.[33]

Literary influences

In Black Boy, Wright discussed a number of authors whose works influenced his own, including H. L. Mencken, Gertrude Stein, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Sinclair Lewis, Marcel Proust and Edgar Lee Masters.

Awards

Wright received several different literary awards during his lifetime including the Spingarn Medal in 1941, the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1939, and the Story Magazine Award.[15][34]

Legacy

Black Boy became an instant best-seller upon its publication in 1945.[35] Wright's stories published during the 1950s disappointed some critics who said that his move to Europe alienated him from African Americans and separated him from his emotional and psychological roots.[36] Many of Wright's works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of New Criticism as the works of younger black writers gained in popularity.[37] During the 1950s Wright grew more internationalist in outlook. While he accomplished much as an important public literary and political figure with a worldwide reputation, his creative work did decline.[38]

While interest in Black Boy ebbed during the 1950s, it has remained one of his best selling books, and there has been a resurgence of interest in it by critics. Black Boy remains a vital work of historical, sociological, and literary significance whose seminal portrayal of one black man's search for self-actualization in a racist society made possible the works of such successive writers as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison. It is generally agreed that Wright's influence in Native Son is not a matter of literary style or technique.[39] His impact, rather, has been on ideas and attitudes, and his work has been a force in the social and intellectual history of the United States in the last half of the 20th century. "Wright was one of the people who made me conscious of the need to struggle", said writer Amiri Baraka.[40]

During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars published critical essays about Wright in prestigious journals. Richard Wright conferences were held on university campuses from Mississippi to New Jersey. A new film version of Native Son, with a screenplay by Richard Wesley, was released in December 1986. Certain Wright novels became required reading in a number of American high schools, universities and colleges.[41]

"Recent critics have called for a reassessment of Wright's later work in view of his philosophical project. Notably, Paul Gilroy has argued that 'the depth of his philosophical interests has been either overlooked or misconceived by the almost exclusively literary enquiries that have dominated analysis of his writing'."[42] "His most significant contribution, however, was his desire to accurately portray blacks to white readers, thereby destroying the white myth of the patient, humorous, subservient black man".[43]

In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. postage stamp. The 61-cent, two-ounce rate stamp is the 25th installment of the literary arts series and features a portrait of Richard Wright in front of snow–swept tenements on the South Side of Chicago, a scene that recalls the setting of Native Son.[44]

In 2009, Wright was featured in a 90-minute documentary about the WPA Writers' Project entitled Soul of a People: Writing America's Story.[45] His life and work during the 1930s is also highlighted in the companion book, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America.[46]

Publications

- Collections

- Richard Wright: Early Works (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of America, 1989),

- Richard Wright: Later Works (Arnold Rampersad, ed.) (Library of America, 1991).

- Drama

- Native Son: The Biography of a Young American with Paul Green (New York: Harper, 1941)

- Fiction

- Uncle Tom's Children (New York: Harper, 1938)

- The Man Who Was Almost a Man (New York: Harper, 1939)

- Native Son (New York: Harper, 1940)

- The Outsider (New York: Harper, 1953)

- Savage Holiday (New York: Avon, 1954)

- The Long Dream (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1958)

- Eight Men (Cleveland and New York: World, 1961)

- Lawd Today (New York: Walker, 1963)

- Rite of Passage (New York: Harper Collins, 1994)

- A Father's Law (London: Harper Perennial, 2008)

- Non-fiction

- How "Bigger" Was Born; Notes of a Native Son (New York: Harper, 1940)

- 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (New York: Viking, 1941)

- Black Boy (New York: Harper, 1945)

- Black Power (New York: Harper, 1954)

- The Color Curtain (Cleveland and New York: World, 1956)

- Pagan Spain (New York: Harper, 1957)

- Letters to Joe C. Brown (Kent State University Libraries, 1968)

- American Hunger (New York: Harper & Row, 1977)

- Black Power: Three Books from Exile: "Black Power"; "The Color Curtain"; and "White Man, Listen!" (Harper Perennial, 2008)

- Essays

- The Ethics Of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch (1937)

- Introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945)

- I Choose Exile (1951)

- White Man, Listen! (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1957)

- Blueprint for Negro Literature (New York City, New York) (1937)[47]

- The God that Failed (contributor) (1949)

- Poetry

- Haiku: This Other World (eds. Yoshinobu Hakutani and Robert L. Tener; Arcade, 1998, ISBN 0-385-72024-6)

- re-issue (paperback): Haiku: The Last Poetry of Richard Wright (Arcade Publishing, 2012).

Notes

- ↑ http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/2031

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Rayson, Ann. "Richard Wright's Life." Modern American Poetry. Nelson, Cary and Brinkman, Bartholomew, eds. Department of English, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign: 2001.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1966). Black Boy. New York: Harper and Row Publishers. ISBN 0-06-083056-5.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1966). Black Boy. New York: Harper and Row Publishers. pp. 135–138. ISBN 0-06-083056-5.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1966). Black Boy. New York: Harper and Row Publishers. pp. 193–197. ISBN 0-06-083056-5.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1966). Black Boy. New York: Harper and Row Publishers. pp. 276–278. ISBN 0-06-083056-5.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1993). Black Boy. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 455–459. ISBN 0-06-081250-8.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1966). Black Boy. New York: Harper and Row Publishers. pp. 182–186. ISBN 0-06-083056-5.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1965). "Richard Wright". In Crossman, Richard. The God That Failed. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 109–10.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1965). "Richard Wright". In Crossman. The God That Failed. p. 121.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1965). "Richard Wright". In Crossman. The God That Failed. pp. 123–26.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1965). "Richard Wright". In Crossman, Richard. The God That Failed. pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1960). "Richard Wright". In Crossman. The God That Failed. pp. 126–34.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1965). "Richard Wright". In Crossman. The God That Failed. pp. 143–45.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wright, Richard (1993). Black Boy. New York: Harper Collins. p. 465.

- ↑ Richard Wright biography.

- ↑ Carol Polsgrove, Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause (2009), pp. 125–28.

- ↑ Carol Polsgrove, Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement (2001), p. 82.

- ↑ Polsgrove, Divided Minds, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Roberts, Brian. Artistic Ambassadors: Literary and International Representation of the New Negro Era. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 153-153, 161.

- ↑ Vuyk, Beb (May 2011). "A Weekend with Richard Wright". PMLA 126 (3): 810. doi:10.1632/pmla.2011.126.3.798.

- ↑ "Richard Wright, Writer, 52, Dies", New York Times, November 30, 1960.

- ↑ Nance, Kevin (2007-02-16). "Celebrating Black History Month: Richard Wright". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "Richard (Nathaniel) Wright (1908–1960)". Books and Authors. 2003. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "Children's Books/Black History; Bookshelf". The New York Times. February 13, 1994.

- ↑ "Ambiguities". The New York Times. February 24, 2008.

- ↑ Hazel Rowley, Richard Wright: The Life and Times, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 177.

- ↑ "Richard N. Wright (1908-1960), Bio-Chronology", Chicken Bones: A Journal for Literary & Artistic African-American Themes.

- ↑ Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (eds), Harlem Renaissance Lives: From the African American National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 555.

- ↑ Rowley (2001), p. 227.

- ↑ "A Richard Wright Chronology", Modern American Poetry.

- ↑ Wright, Richard (1998) [1940]. Native Son. New York: Original 1940 edition by Harper & Brothers, 1998 version by HarperPerennial. pp. 471–474, 478.

- ↑ Julia Wright on Richard Wright Centennial, AfriGeneas Writers Forum. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "The Spingarn Medal, 1915–2007". World Almanac & Book of Facts. World Almanac Education Group, Inc. 2008. p. 256.

- ↑ Levy, Debbie (2007). Richard Wright: A Biography. p. 97. ISBN 9780822567936.

- ↑ Corkery, Caleb (2007). "Richard Wright and His White Audience: How the Author's Persona Gave Native Son Historical Significance". Richard Wright's Native Son. p. 16. ISBN 9789042022973.

- ↑ Goldstein, Philip (2007). "From Communism to Black Studies and Beyond: The Reception of Richard Wright's Native Son". Richard Wright's Native Son. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9789042022973.

- ↑ Mullen, Bill. "Richard Wright (1908–1960)". Modern American Poetry. University of Illinois. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Corkery 2007, pp. 17-28.

- ↑ "Richard Wright – Black Boy". Independent Television Service. Archived from the original on 2008-07-15. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ "Richard Wright". Harper Collins. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Sarah Relyea, Outsider Citizens (New York: Routledge, 2006): 62. Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 147.

- ↑ Duffus, Matthew (1999-01-26). "Richard Wright". The Mississippi Writers Page. University of Mississippi. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ United States Postal Service.

- ↑ Smithsonian Channel.

- ↑ Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America page at Wiley.

- ↑ "Blueprint for Negro Literature", ChickenBones: A Journal.

References

- Yarborough, Richard (2008). Uncle Tom's Children. Introduction (Harper Perennial Modern Classics).

- Meyerson, Gregory (Winter 2008). "Aunt Sue's Mistake: False Consciousness in Richard Wright's 'Bright and Morning Star'". Reconstruction 8.4.

- Graham Barnfield and Joseph G. Ramsey, ed. (Winter 2008). Special Centenary Section on "Facing the Future After Richard Wright". Reconstruction 8.4.

- Reynolds, Guy (2000). ""Sketches of Spain": Richard Wright's Pagan Spain and African-American Representations of the Hispanic". Journal of American Studies: 34.

- Baldwin, James (1988). "Richard (Nathaniel) Wright". Contemporary Literary Criticism (Detroit: Gale) 48: 415–430.

Further reading

- Edwin Berry Burgum, "The Promise of Democracy and the Fiction of Richard Wright," Science & Society, vol. 7, no. 4 (Fall 1943), pp. 338–352. In JSTOR.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Wright (author). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Richard Wright |

- Richard Wright Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Richard Wright Collection (MUM00488) at the University of Mississippi.

- Richard Wright: Black Boy (documentary film)

- Richard Wright's Biography at the Mississippi Writers Page

- Richard Wright at the Independent Television Service

- Richard Wright's Photo & Gravesite

- Biography of Wright and his works

- Brief biography below image of Richard Wright Immortalized 4'09 on 61-cent/2oz USPS stamp (amends above Note#18 URL)

- Summary of Richard Wright's Novels

- Synopsis of Wright's Fiction

- Reviews of Wright's Work

- Critical Reception of Wright's Travel Writings

- Review of The Outsider

- Special Section on "Facing the Future After Richard Wright"

- A Western Man of Color: Richard Wright and the World

- Online text of 12 Million Black Voices

- Excerpt from Black Power

- Online Text of The Color Curtain

- Online Text of Pagan Spain

- Online text of The Long Dream

- Excerpt from The God That Failed

- Online text of Native Son

- Looking for Richard Wright from the Beinecke Library, Yale University

- Richard Wright, Native Son, and the Beinecke: Being Brought to My Senses from the Beinecke Library, Yale University

- Richard Wright s on AALBC.com

- http://www.negritude-agonistes.com/ Christian Filostrat writes that Aimé Césaire told him in 1978 that at the cremation of his friend Richard Wright Césaire could hear the bones explode.

|

_printed_1838.jpg)