Rib cage

| Rib cage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Latin | cavea thoracis |

| Identifiers | |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | rib cage |

| TA | A02.3.04.001 |

| FMA | 7480 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

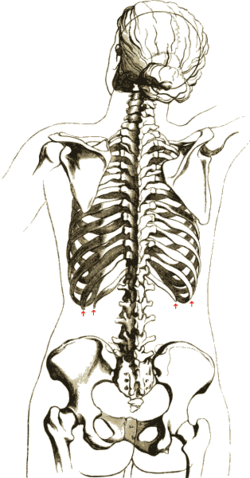

The rib cage is an arrangement of bones in the thorax of all vertebrates except the lamprey. It is formed by the vertebral column, ribs, and sternum and encloses the heart and lungs. In humans, the rib cage, also known as the thoracic cage, is a bony and cartilaginous structure which surrounds the thoracic cavity and supports the pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle), forming a core portion of the human skeleton. A typical human rib cage consists of 24 ribs, the sternum (with xiphoid process), costal cartilages, and the 12 thoracic vertebrae. Together with the skin and associated fascia and muscles, the rib cage makes up the thoracic wall and provides attachments for the muscles of the neck, thorax, upper abdomen, and back.

Structure

Ribs are described based on their location and connection with the sternum. Ribs that articulate directly with the sternum are called true ribs, whereas those that connect indirectly via cartilage are termed false ribs.

Attachment

The terms true and false rib describe rib pairs that are directly or indirectly attached to the sternum. The phrase true rib (Latin: costae verae), or fixed rib, refers to the first seven, or vertebrosternal, rib pairs. The phrase false rib (Latin: costae spuriae), or vertebrochondral ribs refers to the eighth-to-twelfth pairs of ribs. The eighth-to-tenth pairs of ribs connect to the sternum indirectly via the costal cartilages of the ribs above them.[1] Their elasticity allows ribcage movement for respiratory activity.

The phrase floating rib (Latin: costae fluitantes) refers to the two lowermost, the eleventh and twelfth, rib pairs; so-called because they are attached only to the vertebrae–and not to the sternum or cartilage of the sternum. These ribs are relatively small and delicate, and include a cartilaginous tip.[2]

The spaces between the ribs are known as intercostal spaces; they contain the intercostal muscles, nerves, arteries, and veins.

Parts

Each rib consists of a head, neck, and a shaft. The head of rib is the end part closest to the spine with which it articulates. It is marked by a kidney-shaped articular surface which is divided by a horizontal crest into two facets. The superior facet is smaller and articulates with the vertebra above, and the inferior facet articulates with the vertebra of the same number. The transverse process of a thoracic vertebra also articulates with the rib of the same number. The crest gives attachment to the intra-articular ligament.[3] All ribs are attached posteriorly to the thoracic vertebrae.

The neck of the rib is the flattened part that extends laterally from the head. The neck is about 3 cm long, and is placed in front of the transverse process of the lower of the two vertebrae with which the head articulates. Its anterior surface is flat and smooth, whilst its posterior is perforated by numerous foramina and its surface rough, to give attachment to the ligament of the neck.

Its upper border presents a rough crest (crista colli costae) for the attachment of the anterior costotransverse ligament; its lower border is rounded.

On the posterior surface at the junction of the neck and body, and nearer the lower than the upper border, is an eminence—the tubercle; it consists of an articular and a non-articular portion.

The articular portion, the lower and more medial of the two, presents a small, oval surface for articulation with the end of the transverse process of the lower of the two vertebræ to which the head is connected. The non-articular portion is a rough elevation, and affords attachment to the ligament of the tubercle. The tubercle is much more prominent in the upper than in the lower ribs. The angle of a rib (costal angle) may both refer to the bending part of it, and a prominent line in this area, a little in front of the tubercle. This line is directed downward and laterally; this gives attachment to a tendon of the iliocostalis muscle. At this point the rib is bent in two directions, and at the same time twisted on its long axis.

The tubercle of a rib is an eminence on the back surface, at the junction between the neck and the body of the rib. It is nearer to the lower than to the upper border, and nearer the lower than the upper border. The tubercle consists of an articular and a non-articular area. The lower and more medial articular area is a small oval surface for articulation with the transverse process of the lower of the two vertebrae which gives attachment to the head. The higher, non-articular area is a rough elevation which gives attachment to the ligament of the tubercle. The tubercle is much more prominent in the upper ribs than in the lower ribs.

The distance between the angle and the tubercle is progressively greater from the second to the tenth ribs. The area between the angle and the tubercle is rounded, rough, and irregular, and serves for the attachment of the longissimus dorsi muscle.

Bones

The first rib is the most curved and usually the shortest of all the ribs; it is broad and flat, its surfaces looking upward and downward, and its borders inward and outward. The head is small and rounded, and possesses only a single articular facet, for articulation with the body of the first thoracic vertebra. The neck is narrow and rounded. The tubercle, thick and prominent, is placed on the outer border. It bears a small facet for articulation with the transverse process of T1. There is no angle, but at the tubercle the rib is slightly bent, with the convexity upward, so that the head of the bone is directed downward. The upper surface of the body is marked by two shallow grooves, separated from each other by a slight ridge prolonged internally into a tubercle, the scalene tubercle, for the attachment of the scalenus anterior; the anterior groove transmits the subclavian vein, the posterior the subclavian artery and the lowest trunk of the brachial plexus. Behind the posterior groove is a rough area for the attachment of the scalenus medius. The under surface is smooth, and without a costal groove. The outer border is convex, thick, and rounded, and at its posterior part gives attachment to the first digitation of the serratus anterior. The inner border is concave, thin, and sharp, and marked about its center by the scalene tubercle. The anterior extremity is larger and thicker than that of any of the other ribs.

The second rib is the second uppermost rib in humans or second most frontal in animals that walk on four limbs. In humans the second rib is defined as a true rib since it connects with the sternum through the intervention of the costal cartilage anteriorly (at the front). Posteriorly, the second rib is connected with the vertebral column by the second thoracic vertebra. The second rib is much longer than the first rib, but has a very similar curvature. The non-articular portion of the tubercle is occasionally only feebly marked. The angle is slight, and situated close to the tubercle. The body is not twisted, so that both ends touch any plane surface upon which it may be laid; but there is a bend, with its convexity upward, similar to, though smaller than that found in the first rib. The body is not flattened horizontally like that of the first rib. Its external surface is convex, and looks upward and a little outward; near the middle of it is a rough eminence for the origin of the lower part of the first and the whole of the second digitation of the serratus anterior; behind and above this is attached the scalenus posterior. The internal surface, smooth, and concave, is directed downward and a little inward: on its posterior part there is a short costal groove between the ridge of the internal surface of the rib and the inferior border. It contains the intercostal veins and arteries and intercostal nerve.[4]

The ninth rib has a frontal part at the same level as the first lumbar vertebra. This level is called planum transpyloricum, since the pylorus is also at this level.[5]

The tenth rib attaches directly to the body of vertebra T10 instead of between vertebrae like the second through ninth ribs. Due to this direct attachment, vertebra T10 has a complete costal facet on its body.[2]

The eleventh rib and the twelfth rib, the floating ribs, have a single articular facet on the head, which is of rather large size. They have no necks or tubercles, and are pointed at their anterior ends. The eleventh has a slight angle and a shallow costal groove, whereas the twelfth does not. The twelfth rib is much shorter than the eleventh rib, and its head is inclined slightly downward.

Development

In males, expansion of the ribcage is caused by the effects of testosterone during puberty.[6] Thus, males generally have broad shoulders and expanded chests, allowing them to inhale more air to supply their muscles with oxygen.

Variation

Variations in the number of ribs occur. About 1 in 200-500 people have an additional cervical rib, and there is a female predominance.[7] Intrathoracic supernumerary ribs are extremely rare.[8] Bifid or bifurcated ribs, in which the sternal end of the rib is cleaved in two, is a congenital abnormality occurring in about 1.2% of the population. The rib remnant of the 7th cervical vertebra on one or both sides is occasionally replaced by a free extra rib called a cervical rib, which can cause problems in the nerves going to the arm.

In several ethnic groups, most significantly the Japanese, the tenth rib is sometimes a floating rib, as it lacks a cartilaginous connection to the seventh rib.[2]

Function

The human rib cage is a component of the human respiratory system. It encloses the thoracic cavity, which contains the lungs. An inhalation is accomplished when the muscular diaphragm, at the floor of the thoracic cavity, contracts and flattens, while contraction of intercostal muscles lift the rib cage up and out.

Expansion of the thoracic cavity is driven in three planes; the vertical, the anteroposterior and the transverse. The vertical plane is extended by the help of the diaphragm contracting and the abdominal muscles relaxing to accommodate the downward pressure that is supplied to the abdominal viscera by the diaphragm contracting. A greater extension can be achieved by the diaphragm itself moving down, rather than simply the domes flattening. The second plane is the anteroposterior and this is expanded by a movement known as the 'pump handle.' The downward sloping nature of the upper ribs are as such because they enable this to occur. When the external intercostal muscles contract and lift the ribs, the upper ribs are able also to push the sternum up and out. This movement increases the anteroposterior diameter of the thoracic cavity, and hence aids breathing further. Finally, you have the transverse. In this situation, it involves mainly the lower ribs (some say it is the 7th-10th ribs in particular) with the diaphragm's central tendon acting as a fixed point. When the diaphragm contracts, the ribs are able to evert and produce what is known as the 'bucket handle' movement, facilitated by gliding at the costovertebral joints. In this way, the transverse diameter is expanded and the lungs can fill.

Breathing may be assisted by other muscles that can raise the ribs, such as sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis major and minor as well as the scalenes. While under most circumstances, individuals respire via eupnea (normal unlaboured breathing); exercise and other forms of physiological stress can cause the body to require forced expiration, rather than the simple elastic recoil of the thoracic cage, lungs and diaphragm. In this case, muscles are recruited which can help depress the ribs and raise the diaphragm - such as the anterior abdominal wall muscles, excluding the transversus abdominis muscle. Latissimus dorsi can also aid deep, forced expiration.

Another way the thoracic cavity can expand during inhalation is called belly breathing. This also involves a contraction of the diaphragm, but the lower ribs are stabilized so that when the muscle contracts, rather than the central tendon remaining stable and lifting the ribs up, the central tendon moves down, compressing the sub-thoracic cavity and allowing the thoracic cavity and lungs room to expand downward.

These actions produce an increase in volume, and a resulting partial vacuum, or negative pressure, in the thoracic cavity, resulting in atmospheric pressure pushing air into the lungs, inflating them. An exhalation results when the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax, and elastic recoil of the rib cage and lungs expels the air.

The circumference of the normal adult human rib cage expands by 3 to 5 cm during inhalation.[9]

Clinical significance

Rib fractures are the most common injury to the rib cage. These most frequently affect the middle ribs. When several ribs are injured, this can result in a flail chest which is a life-threatening condition.

Abnormalities of the rib cage include pectus excavatum ("sunken chest") and pectus carinatum ("pigeon chest").

Rib removal is the surgical removal of ribs for therapeutic or cosmetic reasons.

Society and culture

Their position can be permanently altered by a form of body modification called tightlacing, which uses a corset to compress and move the ribs.

The ribs, particularly their sternal ends, are used as a way of estimating age in forensic pathology, due to their progressive ossification.[10]

History

The number of ribs as 24 (12 pairs) was noted by the Flemish anatomist Vesalius in his key work of anatomy De humani corporis fabrica in 1543, setting off a wave of controversy, as it was traditionally assumed from the Biblical story of Adam and Eve that men's ribs would number one fewer than women's.[11]

Other animals

The rib cage of a cast of the "Wankel T. rex", a 90% complete Tyrannosaurus skeleton found by Kathy Wankel in eastern Montana in 1988. The cast of the skeleton is in the collection of the University of California Museum of Paleontology and on display at the Valley Life Sciences Building on the UC Berkeley campus in Berkeley, California.

In herpetology, costal grooves refer to lateral indents along the integument of salamanders. The grooves run between the axilla to the groin. Each groove overlies the myotomal septa to mark the position of the internal rib.[12][13]

Birds and reptiles have bony uncinate processes on their ribs that project caudally from the vertical section of each rib.[14]These serve to attach sacral muscles and also aid in allowing greater inspiration. Crocodiles have cartilaginous uncinate processes.

Additional images

|

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rib cage. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human_anatomy, ribs. |

- This article uses anatomical terminology; for an overview, see anatomical terminology.

- Articulation of head of rib

- Terms for anatomical location

- Terms for bones

Notes

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Ribs. http://www1.american.edu/adonahue/k11ribs.htm. [Web]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Saladin, Kenneth (2010). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-07-352569-3.

- ↑ http://www.teachmeanatomy.com/osteology-of-the-thorax/

- ↑ Moore, Dalley & Agur. 2009. Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 6th Edition. 90 Pp. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 0-7817-7525-6, ISBN 978-0-7817-7525-0

- ↑ Bålens ytanatomi (surface anatomy). Godfried Roomans, Mats Hjortberg and Anca Dragomir. Institution for Anatomy, Uppsala. 2008.

- ↑ Testosterone causes expansion of rib cage during puberty as one of secondary sex characteristics.

- ↑ Kurihara Y; Yakushiji YK; Matsumoto J; Ishikawa T; Hirata K (Jan–Feb 1999). "The Ribs: Anatomic and Radiologic Considerations" (PDF). RadioGraphics (Radiological Society of North America) 19 (1): 105–119. doi:10.1148/radiographics.19.1.g99ja02105. ISSN 1527-1323. PMID 9925395. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ↑ Kamano H; Ishihama T; Ishihama H; Kubota Y; Tanaka T; Satoh K (June 1, 2006). "Bifid intrathoracic rib: a case report and classification of intrathoracic ribs" (PDF). Internal Medicine (The Japanese Society of Internal Medicine) 45 (9): 627–630. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1502. PMID 16755094. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ↑ Respiratory system examination citing: Health & Physical Assessment, Mosby-Year Book, inc. School of Nursing, Peking University, 2003

- ↑ Franklin, D (Jan 2010). "Forensic age estimation in human skeletal remains: current concepts and future directions.". Legal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 12 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.09.001. PMID 19853490.

- ↑ "Chapter 19 On the Bones of the Thorax". Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ↑ Duellman, W.E., Trueb, L. (1986). Biology of Amphibians. 670 Pp. McGraw - Hill Book Company, New York, New York, ISBN 0-8018-4780-X, 9780801847806

- ↑ J. W. Petranka. 1998. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. 587 Pp. Smithsonian Institution Press, ISBN 1-56098-828-2, ISBN 978-1-56098-828-1

- ↑ Kardong, Kenneth V. (1995). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. McGraw-Hill. pp. 55, 57. ISBN 0-697-21991-7.

References

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 4th ed. Keith L. Moore and Robert F. Dalley. pp. 62–64

- Principles of Anatomy Physiology, Tortora GJ and Derrickson B. 11th ED. John Wiley and Sons, 2006. ISBN 0-471-68934-3

- De Humani Corporis Fabrica: online English translation of Vesalius' books on human anatomy.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||