Rhombic dodecahedron

| Rhombic dodecahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) | |

| Type | Catalan solid |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Conway notation | jC |

| Face type | V3.4.3.4 rhombus |

| Faces | 12 |

| Edges | 24 |

| Vertices | 14 |

| Vertices by type | 8{3}+6{4} |

| Symmetry group | Oh, BC3, [4,3], (*432) |

| Rotation group | O, [4,3]+, (432) |

| Dihedral angle | 120° |

| Properties | convex, face-transitive edge-transitive, parallelohedron |

Cuboctahedron (dual polyhedron) |

Net |

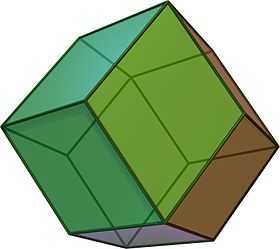

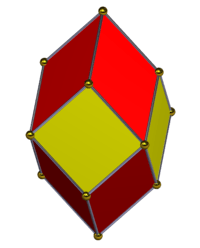

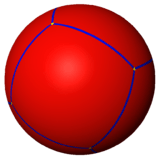

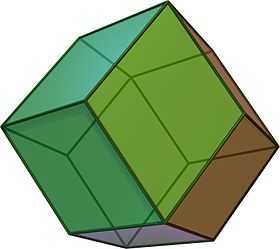

In geometry, the rhombic dodecahedron is a convex polyhedron with 12 congruent rhombic faces. It has 24 edges, and 14 vertices of two types. It is a Catalan solid, and the dual polyhedron of the cuboctahedron.

Properties

The rhombic dodecahedron is a zonohedron. Its polyhedral dual is the cuboctahedron. The long diagonal of each face is exactly √2 times the length of the short diagonal, so that the acute angles on each face measure arccos(1/3), or approximately 70.53°.

Being the dual of an Archimedean polyhedron, the rhombic dodecahedron is face-transitive, meaning the symmetry group of the solid acts transitively on the set of faces. In elementary terms, this means that for any two faces A and B there is a rotation or reflection of the solid that leaves it occupying the same region of space while moving face A to face B.

The rhombic dodecahedron is one of the nine edge-transitive convex polyhedra, the others being the five Platonic solids, the cuboctahedron, the icosidodecahedron and the rhombic triacontahedron.

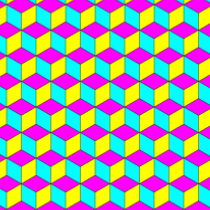

The rhombic dodecahedron can be used to tessellate three-dimensional space. It can be stacked to fill a space much like hexagons fill a plane.

This tessellation can be seen as the Voronoi tessellation of the face-centered cubic lattice. Some minerals such as garnet form a rhombic dodecahedral crystal habit. Honeybees use the geometry of rhombic dodecahedra to form honeycomb from a tessellation of cells each of which is a hexagonal prism capped with half a rhombic dodecahedron. The rhombic dodecahedron also appears in the unit cells of diamond and diamondoids. In these cases, four vertices (alternate threefold ones) are absent, but the chemical bonds lie on the remaining edges.[1]

The graph of the rhombic dodecahedron is nonhamiltonian.

Dimensions

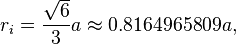

If the edge length of a rhombic dodecahedron is a, the radius of an inscribed sphere (tangent to each of the rhombic dodecahedron's faces) is

the radius of the midsphere is

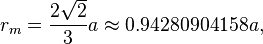

and the radius of the circumscribed sphere is

Area and volume

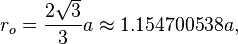

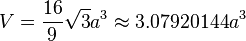

The area A and the volume V of the rhombic dodecahedron of edge length a are:

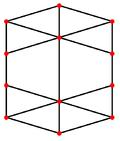

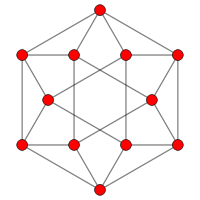

Orthogonal projections

The rhombic dodecahedron has four special orthogonal projections along its axes of symmetry, centered on a face, an edge, and the two types of vertex, threefold and fourfold. The last two correspond to the B2 and A2 Coxeter planes.

| Projective symmetry |

[4] | [6] | [2] | [2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhombic dodecahedron |

|

|

|

|

| Cuboctahedron (dual) |

|

|

|

|

Cartesian coordinates

The eight vertices where three faces meet at their obtuse angles have Cartesian coordinates:

- (±1, ±1, ±1)

The coordinates of the six vertices where four faces meet at their acute angles are the permutations of:

- (±2, 0, 0)

The rhombic dodecahedron can be seen as a degenerate limiting case of a pyritohedron, with permutation of coordinates (±1, ±1, ±1) and (0, 1+h, 1−h2) with parameter h=1.

Variations

The rhombic dodecahedron is a parallelohedron, a space-filling polyhedron. Other symmetry constructions of the rhombic dodecahedron are also space-filling.

For example, with 4 square faces, and 60-degree rhombic faces.

|

Net |

This construction has D2h symmetry, order 8. It can be seen as a cuboctahedron with square pyramids augmented on the top and bottom. It has coordinates:

- (0, 0, ±2)

- (±1, ±1, 0)

- (±1, 0, ±1)

- (0, ±1, ±1)

Related polyhedra

| Symmetry: [4,3], (*432) | [4,3]+ (432) |

[1+,4,3] = [3,3] (*332) |

[3+,4] (3*2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| {4,3} | t{4,3} | r{4,3} r{31,1} |

t{3,4} t{31,1} |

{3,4} {31,1} |

rr{4,3} s2{3,4} |

tr{4,3} | sr{4,3} | h{4,3} {3,3} |

h2{4,3} t{3,3} |

s{3,4} s{31,1} |

= |

= |

= |

||||||||

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | ||||||||||

| V43 | V3.82 | V(3.4)2 | V4.62 | V34 | V3.43 | V4.6.8 | V34.4 | V33 | V3.62 | V35 |

This polyhedron is a part of a sequence of rhombic polyhedra and tilings with [n,3] Coxeter group symmetry. The cube can be seen as a rhombic hexahedron where the rhombi are squares.

| Sym. *n32 [n,3] |

Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyperb. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *332 [3,3] Td |

*432 [4,3] Oh |

*532 [5,3] Ih |

*632 [6,3] p6m |

*732 [7,3] |

*832 [8,3]... |

*∞32 [∞,3] |

[12i,3] | [9i,3] | [6i,3] | [3i,3] | ||

| Figure |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Config. | r{3,3} | r{4,3} | r{5,3} | r{6,3} | r{7,3} | r{8,3} | r{∞,3} | r{12i,3} | r{9i,3} | r{6i,3} | r{3i,3} | |

| Coxeter | ||||||||||||

| Dual uniform figures | ||||||||||||

| Dual conf. |

V(3.3)2 |

V(3.4)2 |

V(3.5)2 |

V(3.6)2 |

V(3.7)2 |

V(3.8)2 |

V(3.∞)2 |

|||||

| Coxeter | ||||||||||||

| Symmetry *4n2 [n,4] |

Spherical | Euclidean | Compact hyperbolic | Paracompact | Noncompact | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *342 [3,4] |

*442 [4,4] |

*542 [5,4] |

*642 [6,4] |

*742 [7,4] |

*842 [8,4]... |

*∞42 [∞,4] |

[iπ/λ,4] | |

| Coxeter | ||||||||

| Quasiregular figures configuration |

4.3.4.3 |

4.4.4.4 |

4.5.4.5 |

4.6.4.6 |

4.7.4.7 |

4.8.4.8 |

4.∞.4.∞ |

4.∞.4.∞ |

| Dual figures | ||||||||

| Coxeter | ||||||||

| Dual (rhombic) figures configuration |

V4.3.4.3 |

V4.4.4.4 |

V4.5.4.5 |

V4.6.4.6 |

V4.7.4.7 |

V4.8.4.8 |

V4.∞.4.∞ |

V4.∞.4.∞ |

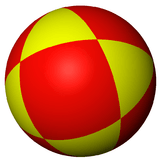

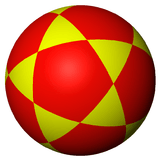

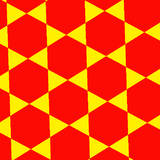

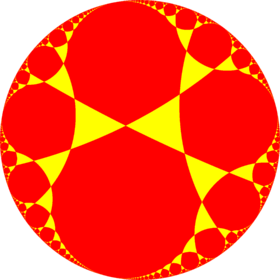

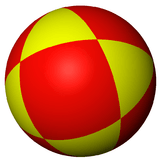

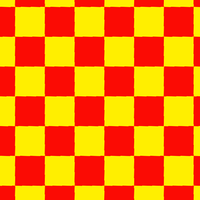

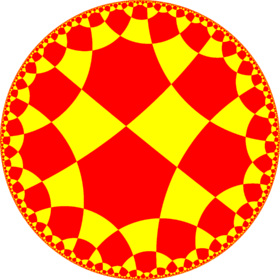

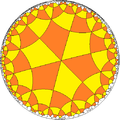

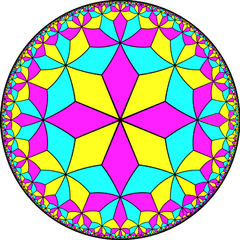

Similarly it relates to the infinite series of tilings with the face configurations V3.2n.3.2n, the first in the Euclidean plane, and the rest in the hyperbolic plane.

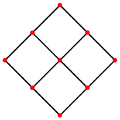

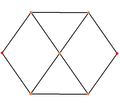

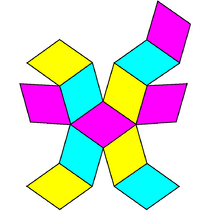

V3.4.3.4 (Drawn as a net) |

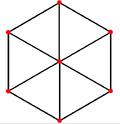

V3.6.3.6 Euclidean plane tiling Rhombille tiling |

V3.8.3.8 Hyperbolic plane tiling (Drawn in a Poincaré disk model) |

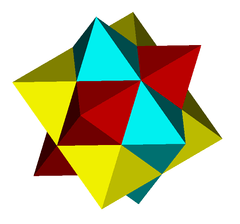

Stellations

Like many convex polyhedra, the rhombic dodecahedron can be stellated by extending the faces or edges until they meet to form a new polyhedron. Several such stellations have been described by Dorman Luke.[2]

The first stellation, often simply called the stellated rhombic dodecahedron, is well known. It can be seen as a rhombic dodecahedron with each face augmented by attaching a rhombic-based pyramid to it, with a pyramid height such that the sides lie in the face planes of the neighbouring faces:

Luke describes four more stellations: the second and third stellations (expanding outwards), one formed by removing the second from the third, and another by adding the original rhombic dodecahedron back to the previous one.

Honeycomb

The rhombic dodecahedron can tessellate space by translational copies of itself. Interestingly, so can the stellated rhombic dodecahedron.

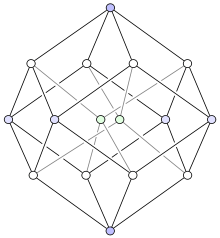

Related polytopes

The rhombic dodecahedron forms the hull of the vertex-first projection of a tesseract to three dimensions. There are exactly two ways of decomposing a rhombic dodecahedron into four congruent parallelepipeds, giving eight possible parallelepipeds. The eight cells of the tesseract under this projection map precisely to these eight parallelepipeds.

The rhombic dodecahedron forms the maximal cross-section of a 24-cell, and also forms the hull of its vertex-first parallel projection into three dimensions. The rhombic dodecahedron can be decomposed into six congruent (but non-regular) square dipyramids meeting at a single vertex in the center; these form the images of six pairs of the 24-cell's octahedral cells. The remaining 12 octahedral cells project onto the faces of the rhombic dodecahedron. The non-regularity of these images are due to projective distortion; the facets of the 24-cell are regular octahedra in 4-space.

This decomposition gives an interesting method for constructing the rhombic dodecahedron: cut a cube into six congruent square pyramids, and attach them to the faces of a second cube. The triangular faces of each pair of adjacent pyramids lie on the same plane, and so merge into rhombuses. The 24-cell may also be constructed in an analogous way using two tesseracts.

See also

- Dodecahedron

- Rhombic triacontahedron

- Rhombille tiling

- Truncated rhombic dodecahedron

- 24-cell – 4D analog of rhombic dodecahedron

- Rhombic dodecahedral honeycomb

- Archimede construction systems

References

- ↑ Dodecahedral Crystal Habit. khulsey.com

- ↑ Luke, D. (1957). "Stellations of the rhombic dodecahedron". The Mathematical Gazette 337: 189–194.

Further reading

- Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23729-X. (Section 3-9)

- Wenninger, Magnus (1983). Dual Models. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511569371. ISBN 978-0-521-54325-5. MR 730208. (The thirteen semiregular convex polyhedra and their duals, Page 19, Rhombic dodecahedron)

- The Symmetries of Things 2008, John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strass, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 21, Naming the Archimedean and Catalan polyhedra and tilings, p. 285, Rhombic dodecahedron )

External links

- Eric W. Weisstein, Rhombic dodecahedron (Catalan solid) at MathWorld

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra – The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

Computer models

- Rhombic Dodecahedron – interactive 3-d model

- Relating a Rhombic Triacontahedron and a Rhombic Dodecahedron, Rhombic Dodecahedron 5-Compound and Rhombic Dodecahedron 5-Compound by Sándor Kabai, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

Paper projects

- Rhombic Dodecahedron Calendar – make a rhombic dodecahedron calendar without glue

- Another Rhombic Dodecahedron Calendar – made by plaiting paper strips

Practical applications

- Archimede Institute Examples of actual housing construction projects using this geometry

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||