Rheobase

Rheobase is a measure of membrane excitability. In neuroscience, rheobase is the minimal current amplitude of infinite duration (in a practical sense, about 300 milliseconds) that results in the depolarization threshold of the cell membranes being reached, such as an action potential or the contraction of a muscle.[1] In Greek, the root "rhe" translates to current or flow, and "basi" means bottom or foundation: thus the rheobase is the minimum current that will produce an action potential or muscle contraction.

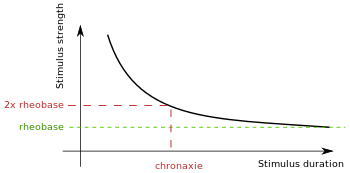

Rheobase can be best understood in the context of the strength-duration relationship (Fig. 1).[2] The ease with which a membrane can be stimulated depends on two variables: the strength of the stimulus, and the duration for which the stimulus is applied.[3] These variables are inversely related: as the strength of the applied current increases, the time required to stimulate the membrane decreases (and vice versa) to maintain a constant effect.[3] Mathematically, rheobase is equivalent to half the current that needs to be applied for the duration of chronaxie, which is a strength-duration time constant that corresponds to the duration of time that elicits a response when the nerve is stimulated at twice rheobasic strength.[3]

The strength-duration curve was first discovered by G. Weiss in 1901, but it was not until 1909 that Louis Lapicque coined the term "rheobase".[4] Many studies are being conducted in relation to rheobase values and the dynamic changes throughout maturation and between different nerve fibers.[5] In the past strength-duration curves and rheobase determinations were used to assess nerve injury; today, they play a role in clinical identification of many neurological pathologies, including as Diabetic neuropathy, CIDP, Machado-Joseph Disease,[6] and ALS.[7]

Strength-Duration Curve

The strength-duration time constant (chronaxie) and rheobase are parameters that describe the strength-duration curve—the curve that relates the intensity of a threshold stimulus to its duration. As the duration of a test stimulus increases, the strength of the current required to activate a single fiber action potential decreases.

The strength-duration curve is a plot of the threshold current (I) versus pulse duration (d) required to stimulate excitable tissue.[4] As mentioned, the two important points on the curve are rheobase (b) and chronaxie (c), which correlates to twice the rheobase (2b). Strength-duration curves are useful in studies where the current required is changed when the pulse duration is changed.[8]

Lapicque's Equation

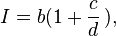

In 1907, Louis Lapicque, a French neuroscientist, proposed his exponential equation for the strength-duration curve. His equation for determining current I:

where b relates to the rheobase value and c relates to the chronaxie value over duration d.

Lapicque's hyperbolic formula combines the threshold amplitude of a stimulus with its duration. This represents the first manageable with physiologically defined parameters that could compare excitability of different objects, reflecting an urgent need at the turn of the 20th century.[4] Lapicque used constant-current, capacitor-discharge pulses to obtain chronaxie for a wide variety of excitable tissues.[4] Rheobase in the Lapicque equation is the asymptote of the hyperbolic curve at very long durations.

Weiss's Equation

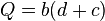

In 1901, G. Weiss proposed another linear equation using a charge Q duration curve. The electrical charge Q can be calculated with the following equation:

or

or

again, where I is the current is measured in amperes multiplied by duration d. b relates to the rheobase value and c relates to the chronaxie value.

Rheobase in the Weiss formula is the slope of the graph. The x-intercept of the Weiss equation is equal to b x c, or rheobase times chronaxie.

This equation suggests that a graph of threshold stimulus strength versus stimulus duration should show a decay toward zero as stimulus duration is increased, so the stimulus strength required to reach threshold is predicted to increase during more protracted stimulation.[4] The strength-duration curve for a typical nerve membrane is slightly skewed from the predicted graph, in that the curve flattens out in response to repetitive stimulation reaching an asymptote representing rheobase.[4] When the duration of a stimulus is prolonged, charge transfer and membrane potential rise exponentially to a plateau (instead of increasing linearly with time).[4][6] When rheobase exceeds the strength of the stimulus, stimulation fails to generate action potentials (even with large values of t); thus if the stimulus is too small, the membrane potential never reaches threshold. The disparity between the shape of the strength-duration curve predicted by Weiss's equation and the one actually observed in neural membranes can be attributed to leakage of charge that occurs under physiological conditions, a feature of the electrical resistance of the membrane.[4][6] Weiss' equation predicts the relationship between stimulus strength and duration for an ideal capacitor with no leakage resistance.

Despite this limitation, Weiss’s equation provides the best fit for strength-duration data and indicates that rheobase and time constant (chronaxie) can be measured from the charge duration curve with a very small margin of error.[9] Weiss used rectangular, constant-current pulses and found that threshold charge required for stimulation increased linearly with pulse duration.[4] He also found that stimulus charge, the product of stimulus current and stimulus duration is proportional to rheobase, so that only two stimulus durations are necessary to calculate rheobase.[6]

Measurement

The use of strength-duration curves in was developed in the 1930s, followed by the use of threshold current measurements for the study of human axonal excitability in the 1970s.[6] Use of these methods in toxic neuropathies has enabled researchers to designate protective factors for many peripheral nerve disorders, and several diseases of the central nervous system (see Clinical Significance).

Nerve excitability examination complements conventional nerve conduction studies by allowing insight into biophysical characteristics of axons, as well as their ion-channel functioning.[10] The protocol is aimed at providing information about nodal as well as internodal ion channels, and the indices are extremely sensitive to axon membrane potential.[10] These studies have provided insight into conditions characterized by changes in resting potential, such as electrolyte concentration and pH, as well as specific ion-channel and pump function in normal and diseased nerves.[11] Furthermore, software programs enabling the calculation of rheobasic and time constant values from both normal and diseased nerves have recently enabled researchers to pinpoint some important factors for a number of pervasive nerve disorders, many of which involve substantial demyelination (see Clinical Significance).[10][11] Supraximal electrical stimulation and measurement of conduction velocity and amplitudes of compound motor (CMAP) and sensory (SNAP) responses provide measures of the number and conduction velocities of large myelinated fibers.[10][11] Additionally, multiple measures of excitability in the TROND protocol permit assessment of ion channels (transient and persistent Na+ channels, slow K+ channels) at nodes of Ranvier by computing stimulus response curves, strength duration time constant (chronaxie), rheobase, and the recovery cycle after passage of an action potential.[10] This is accomplished by applying long polarizing currents to the nerve and measuring the influence of voltage on voltage gated-ion channels beneath myelin.[10]

Neurobiological Significance

The properties of the nodal membrane largely determine the axon's strength-duration properties, and these will change with changes in membrane potential, with temperature, and with demyelination as the exposed membrane is effectively enlarged by the inclusion of paranodal and intermodal membrane.[9] Thus, the strength-duration time constant is a reflection of persistent Na+ channel function, and is furthermore influenced by membrane potential and passive membrane properties.[10] As such, many aspects of nerve excitability testing depend on sodium channel functions: namely, the strength-duration time constant, the recovery cycle, the stimulus-response curve, and the current-threshold relationship. Measuring responses in nerve that are related to nodal function (including strength-duration time constant and rheobase) and internodal function has allowed insight into normal axon physiology as well as normal fluctuations of electrolyte concentrations.[7]

Rheobase is influenced by excitability of the nodal membrane, which increases with hyperpolarization and decreases with depolarization. Its voltage-dependence follows the behavior of persistent sodium channels that are active near threshold and have rapidly activating, slowly inactivating channel properties.[6] Depolarization increases the Na+ current through the persistent channels, resulting in a lower rheobase; hyperpolarization has the opposite effect. The strength-duration time constant increases with demyelination, as the exposed membrane is enlarged by inclusion of paranodal and internodal membrane. The function of the latter of these is to maintain resting membrane potential, so internodal dysfunction significantly affects excitability in a diseased nerve. Such implications are further discussed in Clinical Significance.

Sensory Nerves vs. Motor Nerves

Nerve excitability studies have established a number of biophysical differences between human sensory and motor axons.[6] Even though the diameters and conduction velocities of the most excitable motor and sensory fibers are similar, sensory fibers have significantly longer strength-duration time constants.[11] As a result, sensory nerves have a longer strength-duration time constant and a lower rheobase than motor nerves.[7]

Many studies have suggested that differences in the expression of threshold channels could account for the sensory/motor differences in strength-duration time constant.[11] The differences in strength-duration time constant and rheobase of normal sensory and motor axons are thought to reflect differences in expression of a persistent Na+ conductance.[12] Additionally, sensory axons accommodate more to long-lasting hyperpolarizing currents than do motor axons, suggesting a greater expression of the hyperpolarization-activated inward rectifier channels.[12] Finally, the electrogenic Na+/K+-ATPase is more active in sensory nerves, which have a greater dependence on this pump to maintain resting membrane potential than do motor nerves.[6]

Increases in the strength-duration time constant are observed when this conductance is activated by depolarization, or by hyperventilation.[7] However, demyelination, which exposes internodal membrane with a higher membrane time constant than that of the original node, can also increase strength-duration time constant.[13]

The strength-duration time constant of both cutaneous and motor afferents decreases with age, and this corresponds to an increase in rheobase.[7] Two possible reasons for this age-related decrease in the strength-duration time constant have been proposed. First, nerve geometry might change with age because of axonal loss and neural fibrosis. Secondly, the persistent Na+ conductance might decrease maturation. Significant decreases in threshold for sensory and motor fibers have been observed during ischemia.[7] These decreases in threshold were furthermore associated with significant increases in the strength-duration time constant, appreciably indicating a significant decrease in rheobase current. These changes are thought to be the result of non-inactivating, voltage-dependent Na+ channels, which are active at resting potential.

Clinical Significance

Axonal degeneration and regeneration are common processes in many nerve disorders.[10] As a consequence of myelin remodeling, the internodal length is known to remain persistently short.[10] Little is known about how neurons cope with the increased number of nodes except that there may be a compensatory increase in Na+ channels so that the internodal density is restored.[6] Nevertheless, most extant research findings maintain that regenerated axons may be functionally deficient, as the access to the K+ channel under the paranodal myelin may be increased.[6][10]

In the clinical setting, the function of the internode can only be explored by excitability studies (see Measurement). Experimental observations utilizing threshold measurements to assess excitability of myelinated nerve fibers have indicated that the function of regenerated internodes indeed remains persistently abnormal, with regenerated motor axons displaying increased rheobase and decreased chronaxie—changes that are consistent with abnormal active membrane properties.[10] These studies have furthermore determined that activity-dependent conduction block in myelination was due to hyperpolarization, as well as abnormally increased Na+ currents and increased availability of fast K+ rectifiers.[10] Listed below are findings on the changes in nerve excitability, and therefore the strength-duration time constant, that have been observed within several of the most pervasive nerve disorders.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) affects upper and lower motor systems, with symptoms ranging from muscle atrophy, hyperreflexia, and fasciculations, all of which suggest increased axonal excitability.[7] Many studies have concluded that abnormally decreased K+ conductance results in axonal depolarization, leading to axonal hyperexcitability and the generation of fasciculation.[6][7] ALS patients in these studies demonstrated longer strength-duration time constants and lower values for rheobase than in control subjects.[6][7]

Another study has demonstrated that sensory rheobases were no different in patients from those in age-matched control subjects, whereas motor rheobases were significantly lower.[7] Discovering that motor axons have both a lower rheobase and a longer strength-duration time constant in ALS has prompted the conclusion that motor neurons are abnormally excitable in ALS, with properties more like those of sensory neurons.[7] Changes in the geometry of the nerve due to loss of axons within the peripheral nerve likely cause this shift in rheobase.[7] A logical conclusion of the present data is that there is a greater persistent Na+ conductance at rest in motor axons of patients with ALS than normal.[7]

Machado-Joseph Disease

Machado-Joseph Disease (MJD) is a triplet repeat disease characterized by cerebellar ataxia, pyramidal signs, ophthalmoplegia, and polyneuropathy.[6] Since muscle cramps are a frequent occurrence in MJD, axonal hyperexcitability has been considered to play a role in the disease.[6][10] Research has demonstrated that the strength-duration time constant in MJD patients is significantly longer than in controls, and this corresponds to a significant reduction in rheobase.[6][10] Combined with findings on Na+ channel blockers, this data suggests that the cramps in MJD are likely caused by the increased persistent Na+ channel conductance that may be unregulated during axonal reinnervation (which results from long-term axonal degeneration).[6][10]

Diabetic Polyneuropathy

The hallmark feature of diabetic polyneuropathy is a blend of axonal and demyelinating damage, which results from mechanical demyelination and channel/pump dysfunctions.[6] Diabetic patients have been found to experience a significantly shorter strength-duration time constant and a much higher rheobase than normal patients.[6]

Measurement of sensory conduction in distal nerve segments have shown salient defects in diabetic patients, suggesting that the function of persistent Na+ channels is decreased in diabetics.[6] These experiments have furthermore opened new avenues for preventative drug efficacy. Measurement of chronaxie and rheobase in sural sensory fibers has revealed mild reductions in excitability in diabetics, as evidenced by significant reductions in conduction velocity and chronaxie of sensory fibers with corresponding increases in rheobase.[6] These effects are attributed to the reduced Na+-K+-ATPase activity in axon of diabetic patients, which causes Na+ ions to accumulation intracellularly, as well as a subsequent a decrease in the transmembrane Na+ gradient.[6]

Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) is the most common form of hereditary neuropathy and can be further subdivided into two types: Type 1: demyelinating, and Type 2: axonal.[6] Measurement of chronaxie and rheobase for these diseased nerves have concluded that electrophysiologically, a patient with demyelinating (Type I) CMT demonstrates slow nerve conduction velocity, frequently accompanied by reduced amplitudes of motor and sensory action potentials; moreover, axonal (Type II) CMT can be attributed to impaired interaction between Schwann cells and axons.[6][10] Changes in excitability measures are typically universal and vary little between patients, and this is likely due to the diffuse distribution of demyelination, suggesting changed cable properties associated with short internodes.[10]

Multifocal Motor Neuropathy

Multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) is a rare clinical case, characterized almost entirely by muscle weakness, atrophy, and fasciculations.[6] An important feature of MMN is that the strength-duration constant is significantly small, corresponding to an appreciable increase in rheobase.[6] Both measurements have been shown to been shown to become normalized following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy.[6]

Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) is an immunological demyelinating polyneuropathy.[6][10] As a result of increased paranodal capacitance from demyelination, patients experience increased stimulation threshold, shorter strength-duration time constant, and increased rheobase.[6][10]

See also

References

- ↑ Ashley, et al. "Determination of the Chronaxie and Rheobase of Denervated Limb Muscles in Conscious Rabbits". Artificial Organs, Volume 29 Issue 3 Page 212 - March 2005

- ↑ Fleshman et al. "Rheobase, input resistance, and motor-unit type in medial gastrocnemius motoneurons in the cat." Journal of Neurophysiology, 1981.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Boinagrov, D., et al. (2010). "Strength-duration relationship for extracellular neural stimulation: Numerical and analytical models". Journal of Neurophysiology, 194(2010), 2236–2248.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Geddes, L. A. (2004). "Accuracy limitations of chronaxie values". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 51(1).

- ↑ Carrascal, et al. (2005). "Changes during postnatal development in physiological and anatomical characteristics of rat motoneurons studied in vitro". Brain Research Reviews, 49(2005), 377–387.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 Nodera, H., & Kaji, R. (2006). "Nerve excitability testing in its clinical application to neuromuscular diseases". Clinical Neurophysiology, 117(2006), 1902–1916.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 Mogyoros, I., et al. (1998). "Strength-duration properties of sensory and motor axons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Brain, 121(1998), 851–859.

- ↑ Geddes, L.A., & Bourland, J. D. (1985) "The Strength-Duration Curve". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 32 (6). 458–459.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mogyoros, I., et al. (1995). "Strength-duration properties of human peripheral nerve". Brain, 119(1996), 439–447.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 Krarup, C., & Mihai, M. (2009). "Nerve conduction and excitability studies in peripheral nerve disorders". Current Opinion in Neurology, 22(5), 460–466.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Mogyoros, I. et al. (1997). "Excitability changes in human sensory and motor axons during hyperventilation and ischaemia”. ‘’Brain’’ (1997), 120, 317–325.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bostock H. & Rockwell J. C. (1997) "Latent addition in motor and sensory fibres of human peripheral nerve". J Physiol (Lond) 1997; 498: 277–94.

- ↑ Bostock, H., et al. (1983) "The spatial distribution of excitability and membrane current in normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibers". The Journal of Physiology. (341) 41–58.