Revolutions of 1848

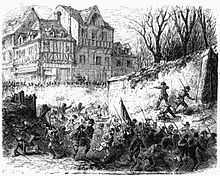

Barricade on the rue Soufflot,[1][2] an 1848 painting by Horace Vernet. The Panthéon is shown in the background. | |

| Date | 23 February 1848-early 1849 |

|---|---|

| Location | Western and Central Europe |

| Also known as | Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples, Year of Revolution |

| Participants | People of France, the German states, the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Italian states, Denmark, Wallachia, Ukraine, Poland, and others |

| Outcome |

Little political change Significant social and cultural change |

.jpg)

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples[3] or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, but within a year, reactionary forces had regained control, and the revolutions collapsed.

The revolutions were essentially bourgeois-democratic in nature with the aim of removing the old feudal structures and the creation of independent national states. The revolutionary wave began in France in February, and immediately spread to most of Europe and parts of Latin America. Over 50 countries were affected, but with no coordination or cooperation among the revolutionaries in different countries. Six factors were involved: widespread dissatisfaction with political leadership; demands for more participation in government and democracy; demands for freedom of press; the demands of the working classes; the upsurge of nationalism; and finally, the regrouping of the reactionary forces based on the royalty, the aristocracy, the army, and the peasants.[4]

The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more forced into exile. The only significant lasting reforms were the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the definitive end of the Capetian monarchy in France. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire, but did not reach Russia, Sweden, Great Britain, and most of southern Europe (Spain, Serbia,[5] Greece, Montenegro, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire).[6]

Origins

.svg.png)

The revolutions arose from such a wide variety of causes that it is difficult to view them as resulting from a coherent movement or social phenomenon. Numerous changes had been taking place in European society throughout the first half of the 19th century. Both liberal reformers and radical politicians were reshaping national governments.

Technological change was revolutionizing the life of the working classes. A popular press extended political awareness, and new values and ideas such as popular liberalism, nationalism and socialism began to emerge. Some historians emphasize the serious crop failures, particularly those of 1846, that produced hardship among peasants and the working urban poor.

Large swaths of the nobility were discontented with royal absolutism or near-absolutism. In 1846, there had been an uprising of Polish nobility in Austrian Galicia, which was only countered when peasants, in turn, rose up against the nobles.[7] Additionally, an uprising by democratic forces against Prussia, planned but not actually carried out, occurred in Greater Poland.

Next, the middle classes began to agitate. Working-class objectives tended to fall in line with those of the middle class. Although Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, working in London, had written The Communist Manifesto (published in German in London on February 21, 1848) at the request of the Communist League (an organization consisting principally of German workers), once they began agitating in Germany following the March insurrection in Berlin, their demands were considerably reduced. They issued their "Demands of the Communist Party in Germany" from Paris in March;[8] the pamphlet only urged unification of Germany, universal suffrage, abolition of feudal duties, and similar middle-class goals.

The middle and working classes thus shared a desire for reform, and agreed on many of the specific aims. Their participations in the revolutions, however, differed. While much of the impetus came from the middle classes, much of the cannon fodder came from the lower. The revolts first erupted in the cities.

Urban workers

The population in French rural areas had risen rapidly, causing many peasants to seek a living in the cities. Many in the bourgeoisie feared and distanced themselves from the working poor. Many unskilled laborers toiled from 12 to 15 hours per day when they had work, living in squalid, disease-ridden slums. Traditional artisans felt the pressure of industrialization, having lost their guilds. Revolutionaries such as Marx built up a following.[9]

The situation in the German states was similar. Parts of Prussia were beginning to industrialize. During the decade of the 1840s, mechanized production in the textile industry brought about inexpensive clothing that undercut the handmade products of German tailors.[10] Reforms ameliorated the most unpopular features of rural feudalism, but industrial workers remained dissatisfied with these and pressed for greater change.

Urban workers had no choice but to spend half of their income on food, which consisted of bread and potatoes. As a result of harvest failures, food prices soared and the demand for manufactured goods decreased, causing an increase in unemployment. During the revolution, to address the problem of unemployment, workshops were organized for men interested in construction work. Officials also set up workshops for women when they felt they were excluded. Artisans and unemployed workers destroyed industrial machines when their social demands were neglected.[11]

Rural areas

Rural population growth had led to food shortages, land pressure, and migration, both within Europe and out from Europe, especially to North America. In the years 1845 and 1846, a potato blight caused a subsistence crisis in Northern Europe. The effects of the blight were most severely manifested in the Great Irish Famine,[12] but also caused famine-like conditions in the Scottish Highlands and throughout continental Europe.

Aristocratic wealth (and corresponding power) was synonymous with the ownership of farm lands and effective control over the peasants. Peasant grievances exploded during the revolutionary year of 1848.

Role of ideas

Despite forceful and often violent efforts of established and reactionary powers to keep them down, disruptive ideas gained popularity: democracy, liberalism, nationalism, and socialism.[13]

In the language of the 1840s, 'democracy' meant universal male suffrage. 'Liberalism' fundamentally meant consent of the governed and the restriction of church and state power, republican government, freedom of the press and the individual. 'Nationalism' believed in uniting people bound by (some mix of) common languages, culture, religion, shared history, and of course immediate geography; there were also irredentist movements. At this time, what are now Germany and Italy were collections of small states. 'Socialism' in the 1840s was a term without a consensus definition, meaning different things to different people, but was typically used within a context of more power for workers in a system based on worker ownership of the means of production.

Events by country or region

.jpg)

Italian states

Although little noticed at the time, the first major outbreak came in Sicily, starting in January 1848. There had been several previous revolts against Bourbon rule; this one produced an independent state that lasted only 16 months before the Bourbons came back. During those months, the constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of an Italian confederation of states. The failed revolt was reversed a dozen years later as the Bourbon kingdom of the Two Sicilies collapsed in 1860–61 with the Risorgimento.

France

The "February Revolution" in France was sparked by the suppression of the campagne des banquets. This revolution was driven by nationalist and republican ideals among the French general public, who believed the people should rule themselves. It ended the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe, and led to the creation of the French Second Republic. This government was headed by Louis-Napoleon, who, after only four years, established the Second French Empire in 1852.

Alexis de Tocqueville remarked in his Recollections of the period, "society was cut in two: those who had nothing united in common envy, and those who had anything united in common terror."[14]

German states

The "March Revolution" in the German states took place in the south and the west of Germany, with large popular assemblies and mass demonstrations. Led by well-educated students and intellectuals,[15] they demanded German national unity, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly. The uprisings were not well coordinated, but had in common a rejection of traditional, autocratic political structures in the 39 independent states of the German Confederation. The middle-class and working-class components of the Revolution split, and in the end, the conservative aristocracy defeated it, forcing many liberals into exile.[16]

Denmark

Denmark had been governed by a system of absolute monarchy since the 17th century. King Christian VIII, a moderate reformer but still an absolutist, died in January 1848 during a period of rising opposition from farmers and liberals. The demands for constitutional monarchy, led by the National Liberals, ended with a popular march to Christiansborg on March 21. The new king, Frederick VII, met the liberals' demands and installed a new Cabinet that included prominent leaders of the National Liberal Party.[17]

The national-liberal movement wanted to abolish absolutism, but retain a strongly centralized state. The king accepted a new constitution agreeing to share power with a bicameral parliament called the Rigsdag. Although army officers were dissatisfied, they accepted the new arrangement which, in contrast to the rest of Europe, was not overturned by reactionaries.[17] The liberal constitution did not extend to Schleswig, leaving the Schleswig-Holstein Question unanswered.

Schleswig

Schleswig, a region containing both Danes and Germans, was a part of the Danish monarchy, but remained a duchy separate from the Kingdom of Denmark. Spurred by pan-German sentiment, Germans of Schleswig took up arms to protest a new policy announced by Denmark's National Liberal government, which would have fully integrated the duchy into Denmark.

The German population in Schleswig and Holstein revolted, inspired by the Protestant clergy. The German states sent in an army, but Danish victories in 1849 led to the Treaty of Berlin (1850) and the London Protocols (1852). They reaffirmed the sovereignty of the King of Denmark, while prohibiting union with Denmark. The violation of the latter provision led to renewed warfare in 1863 and the Prussian victory in 1864.

Habsburg Empire

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements, which often had a nationalist character. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included Austrians, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Croats, Slovaks, Ukrainians/Ruthenians, Romanians, Serbs and Italians, all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to either achieve autonomy, independence, or even hegemony over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

Hungary

Prior to 1848 Hungary was a feudal monarchy and was a large part of the multinational Habsburg Empire. Foreign relations and fiscal and military affairs were directed from Vienna in Austria but internally Hungary was controlled by local nobility that made up 5% of the population. Only the nobility could vote and the peasantry was restricted to feudal serfdom that supported the nobility.[18] The nobility organized its power in the form of the Diet that made up the assemblies that controlled Hungary’s internal issues. Although they claimed they had a continuous state hood for nearly a thousand years, Hungary sought to free itself from Austrian influence.[19] In the spring of 1848 in March the revolutionary trend that had started in France began to ignite protests. The main focus of these protests and revolution was to secure better rights for the people and to have independence from the Habsburg Crown. Lajos Kossuth and some other liberal nobility that made up the Diet appealed to the Habsburg court with demands for representative government and civil liberties in the newly non feudal Hungary.[20]

There were multiple public protests that continued to spread through Hungary with ever increasing demands for rights and independence. On March 15, the protestors sent to the imperial government what is known as the “Twelve Demands”, which included the demand for freedom of press, an independent Hungarian ministry residing in Buda-Pest and responsible to a popularly elected parliament, the formation of a National Guard, complete civil and religious equality, trial by jury, a national bank, a Hungarian army, the withdrawal of foreign troops from Hungary (Austrian troops), the freeing of political prisoners, and the union with Transylvania. On that morning, the demands were read aloud along with poetry by Sandor Petofi with the simple lines of “We swear by the God of the Hungarians. We swear, we shall be slaves no more”.[21] The demands of the Diet were agreed upon on March 18 by Emperors Ferdinand. Even though Hungary would remain part of the Empire through “personal union” with the emperor, a constitutional government would be founded. The Diet then passed the April laws that established equality before the law, a legislature, a hereditary constitutional monarchy, and an end to the transfer and restrictions of land use.[20]

The success of the new Hungarian independent nation caused many reactions from not only the Habsburg Crown, but also non-Magyar peoples of Hungary that felt threatened by Hungarian nationalism. The country, led by Kossuth, was launched into war with the Habsburg Crown which ought to restore its control over the new Hungarian nation.[19] Although Hungary took a national united stand for its freedom, they were defeated when, after struggling against the Hungarian forces, the Habsburg ruler called on the aid of the Russian Czar Nicholas I, who sent 200,000 troops to assist. Subsequently Hungary was subdued and the Austrian government and Habsburg control was restored.[21]

Switzerland

Switzerland, already an alliance of republics, also saw major internal struggle. The creation of the Sonderbund led to a short Swiss civil war in November 1847. In 1848, a new constitution ended the almost-complete independence of the cantons, and transformed Switzerland into a federal state.

Western Ukraine

The center of the Ukrainian national movement was in Eastern Galicia. On April 19, 1848, a group of representatives led by the Greek Catholic clergy launched a petition to the Austrian Emperor. It expressed wishes that in those regions of Galicia where the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) population represented majority, the Ukrainian language should be taught at schools and used to announce official decrees for the peasantry; local officials were expected to understand it and the Ruthenian clergy was to be equalized in their rights with the clergy of all other denominations.[22]

On May 2, 1848, the Supreme Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Council was established. The Council (1848-1851) was headed by the Greek-Catholic Bishop Gregory Yakhimovich and consisted of 30 permanent members. Its main goal was the administrative division of Galicia into Western (Polish) and Eastern (Ruthenian/Ukrainian) parts within the borders of the Habsburg Empire, and formation of a separate region with a political self-governance.[23]

Greater Poland

Polish people mounted a military insurrection against the Prussians in the Grand Duchy of Posen (or the Greater Poland region), a part of Prussia since its annexation in 1815.

Danubian Principalities

A Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist uprising began in June in the principality of Wallachia. Closely connected with the 1848 unsuccessful revolt in Moldavia, it sought to overturn the administration imposed by Imperial Russian authorities under the Regulamentul Organic regime, and, through many of its leaders, demanded the abolition of boyar privilege. Led by a group of young intellectuals and officers in the Wallachian military forces, the movement succeeded in toppling the ruling Prince Gheorghe Bibescu, whom it replaced with a provisional government and a regency, and in passing a series of major liberal reforms, first announced in the Proclamation of Islaz.

Belgium

In Belgium, the uprisings were local and concentrated in the sillon industriel industrial region of the provinces of Liège and Hainaut. The most serious threat of the 1848 revolutions in Belgium was posed by Belgian émigré groups. Shortly after the revolution in France, Belgian migrant workers living in Paris were encouraged to return to Belgium to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republic.[24] Around 6,000 armed émigrés of the "Belgian Legion" attempted to cross the Belgian frontier. The first group, travelling by train, were stopped and quickly disarmed at Quiévrain on 26 March 1848.[25]

The second group crossed the border on 29 March and headed for Brussels.[24] They were confronted by Belgian troops at the hamlet of Risquons-Tout and defeated.[24] Several smaller groups managed to infiltrate Belgium, but the reinforced Belgian border troops were successful and the defeat at Risquons-Tout effectively ended the revolutionary threat to Belgium. The situation in Belgium began to recover that summer after a good harvest, and fresh elections returned a strong majority to the governing party.[24]

Ireland

The Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848 was a small, failed rebellion which broke out in Ballingarry, Co. Tipperary. It was led by the Young Ireland movement, inspired by famine conditions in Ireland and the 1848 rebellions throughout Europe.[26]

Other English-speaking lands

In Britain, the middle classes had been pacified by general enfranchisement in the Reform Act 1832; the consequent agitations, violence, and petitions of the Chartist movement came to a head with their peaceful petition to Parliament of 1848. The repeal in 1846 of the protectionist agricultural tariffs – called the "Corn Laws" – had defused some proletarian fervour.[27]

In the United States, the main impact of the revolutions and their failure was substantially increased immigration, especially from Germany. This, in turn, fuelled the nativist "Know Nothing" movement in the years preceding the American Civil War. The "Know Nothings" were opposed to immigration, especially immigration of German and Irish Catholics and held the Pope, Pius IX, responsible for the 1848 revolutions' failure.

1848 in Canada saw the establishment of responsible government in Nova Scotia and The Canadas, the first such governments in the British Empire outside of Great Britain itself. John Ralston Saul has argued that this development is tied to the revolutions in Europe, but described the Canadian approach to the revolutionary year of 1848 as "talking their way...out of the empire's control system and into a new democratic model", a stable democratic system which has lasted to the present day.[28] Tory and Orange Order in Canada opposition to responsible government came to a head in riots triggered by the Rebellion Losses Bill in 1849. They succeeded in the burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal, but, unlike their counterrevolutionary counterparts in Europe, they were ultimately unsuccessful.

New Grenada

In Spanish Latin America, the Revolution of 1848 appeared in New Grenada, where Colombian students, liberals, and intellectuals demanded the election of General José Hilario López. He took power in 1849 and launched major reforms, abolishing slavery and the death penalty, and providing freedom of the press and of religion. The resulting turmoil in Colombia lasted four decades; from 1851 to 1885, the country was ravaged by four general civil wars and 50 local revolutions.[29]

Brazil

In Brazil, the "Praieira revolt", a movement in Pernambuco, lasted from November 1848 to 1852. Unresolved conflicts left over from the period of the regency and local resistance to the consolidation of the Brazilian Empire that had been proclaimed in 1822 helped to plant the seeds of the revolution.

Legacy and memory

... We have been beaten and humiliated ... scattered, imprisoned, disarmed and gagged. The fate of European democracy has slipped from our hands.

There were multiple memories of the Revolutions. Democrats looked to 1848 as a democratic revolution, which in the long run ensured liberty, equality, and fraternity. Marxists denounced 1848 as a betrayal of working-class ideals by a bourgeoisie indifferent to the legitimate demands of the proletariat. For nationalists, 1848 was the springtime of hope, when newly emerging nationalities rejected the old multinational empires. They were all bitterly disappointed in the short run. The year 1848, at best, was a glimmer of future hope, and at worst, it was a deadweight that strengthened the reactionaries and delayed further progress.[31]

In the post-revolutionary decade after 1848, little had visibly changed, and most historians considered the revolutions a failure, given the seeming lack of permanent structural changes.

Nevertheless, there were a few immediate successes for some revolutionary movements, notably in the Habsburg lands. Austria and Prussia eliminated feudalism by 1850, improving the lot of the peasants. European middle classes made political and economic gains over the next 20 years; France retained universal male suffrage. Russia would later free the serfs on February 19, 1861. The Habsburgs finally had to give the Hungarians more self-determination in the Ausgleich of 1867. The revolutions inspired lasting reform in Denmark, as well as the Netherlands.

In Chile, the 1848 revolutions inspired the 1851 Chilean Revolution.[32]

European states without upheaval

Great Britain, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, the Russian Empire (including Poland and Finland), and the Ottoman Empire were the only major European states to go without a national revolution over this period. Sweden and Norway were little affected. Serbia, though formally unaffected by the revolt as it was a part of the Ottoman state, actively supported the Serbian revolution in the Habsburg Empire.[33]

Russia's relative stability was attributed to the revolutionary groups' inability to communicate with each other. In the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, uprisings took place in 1830–31 (the November Uprising) and 1846 (the Kraków Uprising, notable for being quelled by the anti-revolutionary Galician slaughter). A final revolt took place in 1863–65 (the January Uprising), but none occurred in 1848.

Switzerland and Portugal were also spared in 1848, though both had gone through civil wars in the preceding years (the Sonderbund War in Switzerland and the Liberal Wars in Portugal). The introduction of the Swiss Federal Constitution in 1848 was a revolution of sorts, laying the foundation of Swiss society as it is today.

In the Netherlands, no major unrests appeared because the king, Willem II, decided to alter the constitution to reform elections and effectively reduce the power of the monarchy. While no major political upheavals occurred in the Ottoman Empire as such, political unrest did occur in some of its vassal states. In Serbia, feudalism was abolished in 1838, and power of the Serbian prince was reduced with the Turkish constitution.

See also

References

- ↑ 1848-06-24: "Battle at Soufflot barricades-1848" Location:Rue Soufflot, Paris48°50′48″N 2°20′37″E / 48.846792°N 2.343473°E

- ↑ Mike Rapport (2009). 1848: Year of Revolution. Basic Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-465-01436-1.

The first deaths came at noon on 23 June.

- ↑ Merriman, John, A History of Modern Europe: From the French Revolution to the Present, 1996, p 715

- ↑ R.J.W. Evans and Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, eds., The Revolutions in Europe 1848–1849 (2000) pp v, 4

- ↑ Serbia's Role in the Conflict in Vojvodina 1848-49, Ohio State University, http://www.ohio.edu/chastain/rz/serbvio.htm

- ↑ Nor did it reach Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Portugal, or the Ottoman Empire. Evans and Strandmann (2000) p 2

- ↑ Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0415161118. pp. 295–296.

- ↑ "Demands of the Communist Party in Germany," Marx-Engels Collected Works, vol 7, pp. 3ff (Progress Publishers: 1975–2005)

- ↑ Merriman, John (1996). A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 718.

- ↑ Merriman, 1996, p. 724

- ↑ Breuilly, John ed. Parker, David (2000). Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition. New York: Routledge. p. 114.

- ↑ Helen Litton, The Irish Famine: An Illustrated History, Wolfhound Press, 1995, ISBN 0-86327-912-0

- ↑ Charles Breunig, The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789–1850 (1977)

- ↑ Tocqueville, Alexis de. "Recollections," 1893

- ↑ Louis Namier, 1848: The Revolution of the Intellectuals (1964)

- ↑ Theodote S. Hamerow, Restoration, Revolution, Reaction: Economics and Politics in Germany, 1825–1870 (1958) focuses mainly on artisans and peasants

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Weibull, Jörgen. "Scandinavia, History of." Encyclopædia Britannica 15th ed., Vol. 16, 324.

- ↑ Laszlo Deme. The Society for Equality in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Slavic Review Vol. 31, No. 1 (Mar., 1972), pp. 71-88

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Deme, Laszlo. The Radical Left in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. New York: Eastern European Quarterly, 1976.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "The US and the 1848 Hungarian Revolution." The Hungarian Initiatives Foundation. Accessed March 26, 2015. http://www.hungaryfoundation.org/history/20140707_US_HUN_1848.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Deak, Istvan. The Lawful Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

- ↑ Kost' Levytskyi, The History of the Political Thought of the Galician Ukrainians, 1848-1914, (Lviv, 1926), 17.

- ↑ Kost' Levytskyi, The History of the Political Thought of the Galician Ukrainians, 1848-1914, (Lviv, 1926), 26.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Chastain, James. "Belgium in 1848". Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions. Ohio University. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ↑ Ascherson, Neal (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo (New ed.). London: Granta. pp. 20–1. ISBN 1862072906.

- ↑ Mark Rathbone. 2010, "The Young Ireland Revolt 1848" History Review no.67:21

- ↑ Henry Weisser, "Chartism in 1848: Reflections on a Non-Revolution," Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring, 1981), pp. 12–26 in JSTOR

- ↑ Saul, J.R. (2012). Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine & Robert Baldwin. Penguin Group (Canada).

- ↑ J. Fred Rippy, Latin America: A Modern History (1958) pp 253–4

- ↑ Breunig, Charles (1977), The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789–1850 (ISBN 0-393-09143-0)

- ↑ Robert Gildea, "1848 in European Collective Memory," in Evans and Strandmann, eds. The Revolutions in Europe, 1848–1849 pp 207–235

- ↑ Gazmuri, Cristián (1999). El "1849" chileno: Igualitarios, reformistas, radicales, masones y bomberos (PDF) (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria. p. 104. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Serbia's Role in the Conflict in Vojvodina, 1848-49". Ohiou.edu. 2004-10-25. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

Bibliography

Surveys

- Breunig, Charles (1977), The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789 – 1850 (ISBN 0-393-09143-0)

- Chastain, James, ed. (2005) Encyclopedia of Revolutions of 1848 online from Ohio State U.

- Dowe, Dieter, ed. Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform (Berghahn Books, 2000)

- Evans, R.J.W., and Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, eds. The Revolutions in Europe, 1848–1849: From Reform to Reaction (2000), 10 essays by scholars excerpt and text search

- Pouthas, Charles. "The Revolutions of 1848" in J. P. T. Bury, ed. New Cambridge Modern History: The zenith of European power 1830–70 (1960) pp 389–415 online excerpts

- Langer, William. The Revolutions of 1848 (Harper, 1971), standard overview

- Rapport, Mike (2009), 1848: Year of Revolution ISBN 978-0-465-01436-1 online review, a standard survey

- Robertson, Priscilla (1952), Revolutions of 1848: A Social History (ISBN 0-691-00756-X), despite the subtitle this is a traditional political narrative

- Sperber, Jonathan. The European revolutions, 1848–1851 (1994) online edition

- Stearns, Peter N. The Revolutions of 1848 (1974). online edition

- Weyland, Kurt. "The Diffusion of Revolution: '1848' in Europe and Latin America," International Organization Vol. 63, No. 3 (Summer, 2009) pp. 391–423 in JSTOR

France

- Duveau, Georges. 1848: The Making of a Revolution (1966)

- Fasel, George. "The Wrong Revolution: French Republicanism in 1848," French Historical Studies Vol. 8, No. 4 (Autumn, 1974), pp. 654–677 in JSTOR

- Loubère, Leo. "The Emergence of the Extreme Left in Lower Languedoc, 1848–1851: Social and Economic Factors in Politics," American Historical Review (1968), v. 73#4 1019–1051 in JSTOR

Germany and Austria

- Deak, Istvan. The Lawful Revolution: Louis Kossuth and the Hungarians, 1848–1849 (1979)

- Hahs, Hans J. The 1848 Revolutions in German-speaking Europe (2001)

- Hewitson, Mark. "'The Old Forms are Breaking Up, ... Our New Germany is Rebuilding Itself': Constitutionalism, Nationalism and the Creation of a German Polity during the Revolutions of 1848–49," English Historical Review, Oct 2010, Vol. 125 Issue 516, pp 1173–1214 online

- Macartney, C. A. "1848 in the Habsburg Monarchy," European Studies Review, 1977, Vol. 7 Issue 3, pp 285–309 online

- O'Boyle Lenore. "The Democratic Left in Germany, 1848," Journal of Modern History Vol. 33, No. 4 (Dec., 1961), pp. 374–383 in JSTOR

- Robertson, Priscilla. Revolutions of 1848: A Social History (1952), pp 105–85 on Germany, pp 187–307 on Austria

- Sked, Alan. The Survival of the Habsburg Empire: Radetzky, the Imperial Army and the Class War, 1848 (1979)

- Vick, Brian. Defining Germany The 1848 Frankfurt Parliamentarians and National Identity (Harvard University Press, 2002) ISBN 978-0-674-00911-0).

Italy

- Ginsborg, Paul. "Peasants and Revolutionaries in Venice and the Veneto, 1848," Historical Journal, Sep 1974, Vol. 17 Issue 3, pp 503–550 in JSTOR

- Ginsborg, Paul. Daniele Manin and the Venetian Revolution of 1848–49 (1979)

- Robertson, Priscilla (1952). Revolutions of 1848: A Social History (1952) pp 309–401

Other

- Feyzioğlu, Hamiyet Sezer et al. "Revolutions of 1848 and the Ottoman Empire," Bulgarian Historical Review, 2009, Vol. 37 Issue 3/4, pp 196–205

Historiography

- Dénes, Iván Zoltán. "Reinterpreting a 'Founding Father': Kossuth Images and Their Contexts, 1848–2009," East Central Europe, April 2010, Vol. 37 Issue 1, pp 90–117

- Hamerow, Theodore S. "History and the German Revolution of 1848," American Historical Review Vol. 60, No. 1 (Oct., 1954), pp. 27–44 in JSTOR

- Jones, Peter (1981), The 1848 Revolutions (Seminar Studies in History) (ISBN 0-582-06106-7)

- Mattheisen, Donald J. "History as Current Events: Recent Works on the German Revolution of 1848," American Historical Review, Dec 1983, Vol. 88 Issue 5, pp 1219–37 in JSTOR

- Rothfels, Hans. "1848 – One Hundred Years After," Journal of Modern History, Dec 1948, Vol. 20 Issue 4, pp 291–319 in JSTOR

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Revolutions of 1848. |

| ||||||||||||||