Requiem (Reger)

| Requiem | |

|---|---|

| by Max Reger | |

|

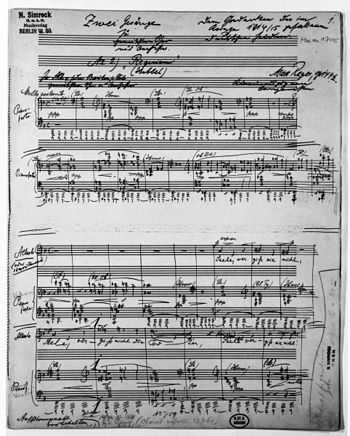

Page from the autograph of the Requiem, part of Zwei Gesänge für gemischten Chor mit Orchester, first page of Nr.2) Requiem | |

| Key | D minor |

| Catalogue | Op. 144b |

| Text | "Requiem" by Friedrich Hebbel |

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1915 |

| Dedication | Soldiers who fell in the War |

| Performed | 16 July 1916 |

| Published | 1916 – by N. Simrock |

| Duration | 18 minutes |

| Scoring | |

Max Reger's Requiem, also known as the Hebbel Requiem, Op. 144b, is a late Romantic setting of Friedrich Hebbel's poem "Requiem" for alto (or baritone) solo, chorus and orchestra. Written in 1915, it is Reger's last finished choral work with orchestra. He dedicated it: "Dem Andenken der im Kriege 1914/15 gefallenen deutschen Helden" (To the memory of the German heroes who fell in the War 1914/15).

Reger had approached the topic before; In 1912, he composed Requiem for men's chorus on the same poem as the final part of his Op. 83, and in 1914 he began composing a setting of the Latin Requiem in memory of the victims of the war. It remained a fragment and was later assigned the name and work number Lateinisches Requiem (Latin Requiem), Op. 145a.

The Hebbel Requiem was published in 1916, after the composer's death, by N. Simrock. It was published together with another choral composition, Der Einsiedler (The Hermit), Op. 144a, on words of Joseph von Eichendorff, as Zwei Gesänge für gemischten Chor mit Orchester (Two songs for mixed chorus with orchestra), Op. 144.

Max Beckschäfer arranged the monumental but rather short work for soloist, choir and organ in 1985.

History

Brahms had opened the way in Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem) to compose a Requiem about rest for the dead, which is non-liturgical and not in Latin.[1] The work known as Reger's Requiem, Op. 144b, is also not a setting of the Requiem in Latin, but of a German poem of the same title written by the dramatist Friedrich Hebbel, beginning with: "Seele, vergiß sie nicht, Seele, vergiß nicht die Toten" (O soul, forget them not, o soul, forget not the dead).[2][3][4] Peter Cornelius had composed a requiem motet on these words for a six-part chorus in 1863 as a response to the author's death.[5] Reger wrote his first setting of the poem in 1912 in Meiningen, where he had worked since 1911 as a Hofkapellmeister of Duke Georg II of Sachsen-Meiningen.[6] Titled Requiem, it was the final part of Zehn Lieder für Männerchor (Ten songs for men's voices), Op. 83.[7] In 1914, after the outbreak of World War I, he began to compose a setting of the Latin Requiem, which he intended to dedicate to the soldiers who fell in the war.[8] The work remained unfinished and was later assigned the name and work number Lateinisches Requiem, Op. 145a. It was first performed by conductor Fritz Stein , Reger's friend and biographer, in Berlin in 1938.[9]

In 1915, a year before his own death, Reger moved to Jena and set the poem again, this time for a solo voice (alto or baritone), chorus and orchestra.[10][11] The Requiem, Op. 144b, was combined with Der Einsiedler (The Hermit), Op. 144a, on words of Joseph von Eichendorff as Zwei Gesänge für gemischten Chor mit Orchester (Two songs for mixed chorus with orchestra), Op. 144. He wrote as a dedication in the autograph of the Requiem: "Dem Andenken der im Kriege 1914/15 gefallenen deutschen Helden" (To the memory of the German heroes who fell in the War 1914/15).[9][12][13]

The Requiem was first performed on 16 July 1916, after the composer's death.[14] The work was first published by N. Simrock in 1916, edited by Ulrich Haverkampf,[15] and in 1928 by Edition Peters,[16] with the performance duration given as 18 minutes.[17]

Lateinisches Requiem

Reger aimed to write a choral work "großen Stils" (in great style).[18] In the fall of 1914, he was in discussions with a theologian in Giessen about a project for a composition possibly to be called "Die letzten Dinge (Jüngstes Gericht u. Auferstehung)" "(The Last Things [Final Judgment and Resurrection])".[19] Karl Straube, who had premiered several of his organ works, proposed that he compose instead the traditional Latin Requiem, because Die letzten Dinge would only be a variation on Brahms' German Requiem.[19] Following the advice, Reger managed the composition of the introit and Kyrie, combining both texts in one movement. He announced the composition project for soloists, chorus, orchestra and organ to his publisher on 3 October 1914.[19] The Dies irae remained unfinished.[20][21] Reger wrote to Fritz Stein that he was in the middle of composing it, but interrupted the work after the line "statuens in parte dextra".[22]

The work is Reger's only choral composition using a solo quartet. The four "Klangapparate" are used like the several choirs in compositions by Schütz.[23] The first movement opens with a long organ pedal point, which has been compared to the beginning of Wagner's Das Rheingold and Brahms' German Requiem.[23]

The first movement was not performed until 1938, then with a German text adapted to suit Nazi ideas.[23] It was published in 1939 by the Max Reger Society, titled Totenfeier (Funeral rite).[24] The unfinished Dies irae was first published in 1974.[23]

Hebbel Requiem

Poem

The title of Hebbel's poem Requiem alludes to Requiem aeternam, rest eternal, the beginning of the Mass for the Dead. Hebbel writes indeed about the rest of the dead, but in a different way.[3] In the first lines, "Seele, vergiß sie nicht, Seele, vergiß nicht die Toten" (O soul, forget them not, o soul, forget not the dead), the speaker addresses his own soul not to forget the dead. The addressing of the soul reminds of some psalms, such as Psalm 103, "Bless the Lord, o my soul". The opening lines are repeated in the centre of the poem and also as its conclusion. The first section so framed describes the dead as hovering around you, shuddering, deserted (Sieh, sie umschweben dich, schauernd, verlassen) and imagines them, nurtured by love, to enjoy one last time their final glow of life. The second section pictures what will happen if you forget them: stiffening first, then seizure by the storm of the night through an endless desert full of battle for renewed being.[25]

Music

Reger's Hebbel Requiem is in one movement, following mainly the structure of the poem but with variations, resulting in a structure of different moods, with the beginning recalled in the centre and in the end. The following table is based on the score and the analysis by Katherine FitzGibbon.[26] The translation of the incipits is given as in the liner notes of the 2009 recording in the translation by Richard Stokes.[27] The four parts SATB of the chorus are often divided. The key is D minor, as is Mozart's Requiem. The tempo in common time is marked Molto sostenuto, kept with only slight modifications by stringendo and ritardando until the most dramatic section, marked Più mosso (moving more) and later Allegro, returning to the first tempo for the conclusion.

| Section | Text | Translation | Vocal | Marking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Seele, vergiß sie nicht | Soul, forget them not | Solo | Molto sostenuto |

| Sieh, sie umschweben dich | See, they hover around you | SSAATTBB | ||

| B | und in den heiligen Gluten | And in the holy ardour | SATTBB | |

| A | Seele, vergiß sie nicht | Soul, forget them not | Solo | |

| Sieh, sie umschweben dich | See, they hover around you | SSAATTBB | ||

| C | und wenn du dich erkaltend ihnen verschließest | And if, growing cold | SATB | |

| Dann ergreift sie der Sturm der Nacht | The storm of night then seizes them | SATB | Più mosso – Molto sostenuto – Allegro | |

| A | Seele, vergiß sie nicht | Soul, forget them not | Solo SATB (chorale) | Molto sostenuto |

The short instrumental introduction is based on a pedal point for several measures, reminding of the openings of Bach's St John Passion and St Matthew Passion, Mozart's Requiem and Reger's previous Latin Requiem.[28] In a pattern strikingly similar to the beginning of A German Requiem, the bass notes are repeated, here on an extremely low D, lower even than the opening of Wagner's Das Rheingold on E flat.

Reger on a 1910 postcard

In the autograph, Reger wrote the many necessary ledger lines (rather than using the symbol an octave lower), perhaps in order to stress the depth. The soloist alone sings the intimate appellation (A) Seele, vergiß sie nicht in a melody simple as a chorale, repeating the first line after the second. Throughout the piece the soloist sings only these words, in the beginning and in the repeats. The chorus, divided in eight parts, illustrates the hovering in mostly homophon chords, marked ppp, in a fashion reminiscent of Heinrich Schütz.[29] In section B, the chorus is divided in 4 to 6 parts, set in more independent motion. The soloist sings similar to the first time, but repeats the second line once more while the chorus sings about the hovering as before. In section C, the chorus literally stiffens on a dissonant 5-part chord fortissimo on the word erstarren. In great contrast, a storm is depicted in dense motion of four parts imitating a theme in triplets. In the conclusion the soloist begins as before but this time finally the chorus joins in the words of the appellation. The soloist introduces a new wording Vergiß sie nicht, die Toten, repeated by the chorus (espressivo, dolcissimo) on the melody of the chorale "O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden" which Bach used in his St Matthew Passion in five verses.[29] The melody is not repeated, as in the original, but continued for half of a line. Reger is known for quoting chorales in general and this one in particular, mostly referring to its last stanza "Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden". The quoted words would then be "Wenn ich den Tod soll leiden, so tritt du denn herfür. Wenn mir am allerbängsten" (When I my death must suffer, Come forth thou then to me! And when most anxious trembling).[30][31] Reger completes the chorale setting in his way for the chorus, while the solo voice repeats "Seele, vergiß nicht die Toten".

Debra Lenssen wrote in her thesis (2008) about Reger's music in his last choral works with orchestra:

As their composer's final completed works for chorus and orchestra, Der Einsiedler and Requiem, Op. 144a and 144b, demonstrate Max Reger's mature ability when setting poems of recognized literary merit. These powerful single-movement works from 1915 defy many stereotypes associated with their composer. They manifest a lyrical beauty, a dramatic compactness, and an economy of musical means. The central theme of both is mortality and death. In these challenging works, his mastery of impulse, technique, and material is apparent. Op. 144 constitutes both a continuation of Reger's choral/orchestral style in earlier works and, by dint of the composer's death as a mid-aged man, the culmination of it.[32]

Versions for piano and organ

The Requiem employs a large orchestra[16] and requires a chorus to match. Therefore it has been performed only rarely. Reger himself wrote a version for piano.[27] To make the remarkable music more accessible, composer and organist Max Beckschäfer arranged the work for voice, chorus and organ in 1985.[33] The organ version was premiered in the Marktkirche Wiesbaden, where Reger had played the organ himself when he had lived there starting in 1891.[34] Gabriel Dessauer conducted a project choir, later known as the Reger-Chor.[35] Beckschäfer was the organist. The choir, expanded by singers from Belgium to the Reger-Chor-International, performed the work again in 2001 with organist Ignace Michiels from the St. Salvator's Cathedral of Bruges, both in the Cathedral of Bruges and in St. Bonifatius, Wiesbaden (recorded live).[36] They performed it a third time in 2010 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Reger-Chor.[37]

Recordings

- Max Reger, Chorstücke, Max van Egmond, Junge Kantorei, Symphonisches Orchester Berlin, conductor Joachim Martini, recorded live in the Berliner Philharmonie, Teldec 1969

- Max Reger Requiem, Op. 144b; Lateinisches Requiem, Op. 145a; Dies irae, Marga Höffgen , North German Radio Choir and Symphony Orchestra, conductor: Roland Bader, Koch Schwann 1979[9][38]

- Max Reger Orchesterlieder, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, St Michaelis Choir Hamburg, Monteverdi-Chor Hamburg, Philharmoniker Hamburg, conductor Gerd Albrecht, Orfeo 1990[39]

- Hebbel Requiem (organ version), Reger-Chor-International, organist Ignace Michiels, conductor Gabriel Dessauer, 2001[37]

- Max Reger (1873-1916) / Choral Works (piano version), Alexander Learmonth, Consortium, pianist Christopher Glynn, conductor Andrew-John Smith, 2009[27][40]

References

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 1.

- ↑ Lied 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gedichte 2010.

- ↑ McDermott 2010, pp. 201,217.

- ↑ Cornelius 2004.

- ↑ Karlsruhe 1911 2010.

- ↑ Boosey 83 2010.

- ↑ Karlsruhe 1914 2010.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bader 2009.

- ↑ Eckle 2014.

- ↑ Karlsruhe 1915 2010.

- ↑ Katzschmann 2010.

- ↑ Moldenhauer 2010.

- ↑ Requiem, song for alto or baritone, chorus & orchestra, Op. 144b at AllMusic

- ↑ Karlsruhe vocal 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Peters 2010.

- ↑ Peters de 2010.

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 FitzGibbon 2014, p. 10.

- ↑ Grim 2005.

- ↑ Sprondel 2014, p. 9.

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 FitzGibbon 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 14.

- ↑ McDermott 2010, pp. 201.

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 15.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Downes 2010.

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 FitzGibbon 2014, p. 17.

- ↑ FitzGibbon 2014, p. 18.

- ↑ Schönstedt 2002.

- ↑ Lenssen 2008.

- ↑ Reger 2010.

- ↑ Karlsruhe 1892 2010.

- ↑ Hoernicke 2001.

- ↑ Orgue 2010.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Hoernicke 2010.

- ↑ Gramophone 1982.

- ↑ Presto 2010.

- ↑ Dixon 2010.

Bibliography

Scores

Books

- Lenssen, Debra (7 July 2008). "Max Reger's final choral/orchestral work: a study of opus 144 as culmination within continuity". ohiolink.edu.

- McDermott, Pamela (2010). "The Requiem Reinvented: Brahms‘s Ein deutsches Requiem and the Transformation from Literal to Symbolic" (PDF). p. 201 of 226, 1.3 MB. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- Schönstedt, Rolf (2002). 7. Max Reger – Das Geistliche Lied als Orgellied – eine Gattung entsteht (in German). Hochschule für Kirchenmusik Herford.

Im 2.Teil zitiert der Sopran den c.f. O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden original, ohne Wiederholung bis zur ersten Halbzeile nach dem Stollen, ... Inbegriff dieses Passionsliedes war für Reger wohl stets die 9. Strophe Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden..., was aus einem Briefzitat an Arthur Seidl 1913 als bewiesen erscheint: 'Haben Sie nicht bemerkt, wie durch alle meine Sachen der Choral hindurchklingt: Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden?'

- Sprondel, Friedrich (2014). "Und die Toten werden die Stimme Gottes hören ..." (PDF) (in German). Bachakademie. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

Journals

- FitzGibbon, Katherine (2014). "Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger's Requiems" (PDF). The Choral Scholar (National Collegiate Choral Organization) 4. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

Newspapers

- Hoernicke, Richard (2001). "Wenn Freunde musizieren" (in German). Wiesbadener Tagblatt.

- Hoernicke, Richard (2010). "Gelungenes Finale der Musikwochen" (in German). Allgemeine Zeitung.

Online sources

- Dixon, Gavin (2010). "Max Reger (1873-1916) / Choral Works". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Downes, Michael (2010). "Requiem, Op 144b". Hyperion Records. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Eckle, Georg-Albrecht (2014). "Nur eine kleine Zeit / Max Reger's "Requiem"". Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Grim, William (2005). "Lateinisches Requiem für Soli, Chor und Orchester, Op. 145a". Jürgen Höflich. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Katzschmann, Christian. "Max Reger (1873–1916) Requiem, Op. 144b (Hebbel)" (in German). musiktext.de. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Requiem, song for alto or baritone, chorus & orchestra, Op. 144b at AllMusic

- "Max Reger (1873–1916) Requiem, Op. 144b/Op. 145a/Dies irae". classics-glaucus. 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Max Reger: Requiem, Op. 83/10". Boosey & Hawkes. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Peter Cornelius (1824–1874) Seele, vergiss sie nicht Requiem". musicweb-international.com. 2004. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Friedrich Hebbel: "Requiem"" (in German). Deutsche Gedichtebibliothek. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Reger. Requiem, Op. 144b". Gramophone. 1982.

- "Max Reger Chronology 1892". Max-Reger-Institut. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Max Reger Chronology 1911". Max-Reger-Institut. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Max Reger Chronology 1914". Max-Reger-Institut. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Max Reger Chronology 1915". Max-Reger-Institut. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Max Reger Werke – Vocal music". Max-Reger-Institut. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Requiem" (in German). The Lied and Art Song Texts Page. 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Zwei Gesänge für gemischten Chor mit Orchester". The Moldenhauer Archives of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "#2 Gabriel Dessauer, Ignace Michiels" (in French). France Orgue. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Reger, Max Requiem Op.144b". Edition Peters. 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- "Reger, Max: Requiem, Op. 144b". Edition Peters. 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- "Reger: Requiem". prestoclassical.co. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Max Reger Kompositionen" (in German). maxreger.de. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

External links

- Requiem compositions of Max Reger on requiemsurvey

- Entries for the Requiem, Op. 144b on WorldCat