Replacement migration

In demography, replacement migration is the migration needed for a region to achieve a particular objective (demographic, economic or social).[1] Generally, studies using this concept have as an objective to avoid the decline of total population and the decline of the working-age population. Projections calculating migration replacement are primarily demographics and theoretical exercises and not forecasts or recommendations.

The concept of replacement migration may vary according to the study and depending on the context in which it applies. It may be a number of annual immigrants,[2] a net migration,[3] an additional number of immigrants compared to a reference scenario,[4] etc.

Types of replacement migration

Replacement migration may take several forms because several scenarios of projections population can achieve the same aim. However, two forms predominate: minimal replacement migration and constant replacement migration.

Minimal replacement migration

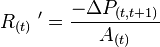

Replacement migration is a minimum migration without surplus to achieve a chosen objective. This form of replacement migration may results in large fluctuations between periods. Its calculation will obviously depend on the chosen objective. For example, Marois (2008) calculates the gross number of immigrants needed to prevent total population decline in Quebec. The formula is then the following:

Where:

- R(t)' = Replacement Migration avoiding the decline of population in year t

- A(t) = retention rate of immigrants year t, defined by (1 - instantaneous departure rate)

- ∆P(t,t+1) = change in the total population in the time interval t, t+1

Constant replacement migration

The constant replacement migration does not fluctuate and remains the same throughout the projection. For example, it will be calculated with a projection providing a migration of X throughout the temporal horizon.

Results

The raw results of replacement migration are not necessarily comparable depending on the type of replacement migration used by the author. Nevertheless, major demographics conclusions are recurrent:

- The replacement migration reached impossible levels in practice to avoid aging the population, to maintain dependency ratio or influence significantly the age structure of a region.

- For regions with a relatively high fertility rate, replacement migration avoiding a decline in the total population or the working age is not excessively high. However, for regions with very low fertility rate, migration replacement is very high and unrealistic.

- The level of fertility is a much more important than the Immigration on aging and age structure.

- The principal effect of immigration is on population effective without substantially modifying the structure.

Examples of results

Replacement migration to prevent the total population decline (annual average):

- Germany: 340 000 (net)

- Canada: 76 000 (number of immigrants)

- United States: 130 000 (net)

- Europe: 1 900 000 (net)

- Japan: 340 000 (net)

- Quebec: 40 000 (number of immigrants)

- Russia 500 000 (net)

- Slovenia: 6 000 (additional immigrants relative to the reference)

Replacement migration to prevent the decline of population of working age (annual average)

- Germany: 490 000 (net)

- Canada: 165 000 (number of immigrants)

- United States: 360 000 (net)

- Europe: 3 230 000 (net)

- Japan 650 000 (net)

- Quebec: 70 000 (number of immigrants)

- Russia: 715 000 (net)

- Slovenia: 240 000 (additional immigrants relative to the reference)

Criticism

Two reasons make replacement migration unnecessary. The first reason is that there is nothing inherently wrong with a declining population. Although countries with declining populations may suffer economic consequences, such populations can establish durable equilibriums with their environment. This is the theory of degrowth which promotes downscaling of production and consumption.

The second reason is that the receiving country stimulates women to give birth to more children. An increased fertility rate counters the need for replacement immigration.

Bibliography

- Bijak, Jakub et al. 2005. « Replacement Migration Revisited: Migratory Flows, Population and Labour Force in Europe, 2002–2052 » In UN ECE Work Session on Demographic Projections, Vienne, 21-23 septembre 2005, 37 p.

http://circa.europa.eu/irc/dsis/jointestatunece/info/data/paper_Bijak.pdf

- Jared Diamond, Guns, germs and steel. A short history of everybody for the last 13'000 years, 1997.

- Marois, Guillaume. 2007. « Démystification de l’impact de l’immigration sur la démographie québécoise : des résultats surprenants », Mémoire déposé lors de la Consultation publique en vue de la planification triennale des niveaux d’immigration pour la période 2008-2010, Commission de la culture, Gouvernement du Québec, 15 p.

http://www.bibliotheque.assnat.qc.ca/01/mono/2007/10/949645.pdf

- Marois, Guillaume. 2008. « La « migration de remplacement » : un exercice méthodologique en rapport aux enjeux démographiques du Québec », Cahier québécois de démographie, vol. 37, n° 2, 2008, p. 237-261

http://www.erudit.org/revue/cqd/2008/v37/n2/038132ar.pdf

- Statistique Canada. 2002. « La fécondité des immigrantes et de leurs filles au Canada », Rapport sur l’état de la population du Canada, rédigé par Alain Bélanger et Stéphane Gilbert. Ottawa (Ont.) : Statistique Canada, pp. 135–161

http://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/app/DocRepository/1/fra/bac/pdf/2006_09_22_belanger_f.pdf

- United Nations. 2000. Replacement Migration, UN Population Division, New York (É-U), 143 p.

http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/migration/execsumFrench.pdf