Religious views on truth

Religious views on truth vary from religion and cultures around the world.

Buddhism

The Four Noble Truths

The Four Noble Truths are the most fundamental Buddhist teachings and appear countless times throughout the most ancient Buddhist texts, the Pali Canon. They arose from Buddha's enlightenment and are regarded in Buddhism as deep spiritual insight, not as philosophical theory, with Buddha noting in the Samyutta Nikaya: "These Four Noble Truths, monks, are actual, unerring, not otherwise. Therefore, they are called noble truths."[1]

The Four Noble Truths (Catvāry Āryasatyāni) are as follows:

- The truth that suffering exists (Dukkha).

- The truth that suffering exists with a root cause (craving).

- The truth that suffering can be eliminated (Nirvana).

- The truth that there is a way to eliminate suffering known as the Noble Eightfold Path.

Two Truths Doctrine

The Two Truths Doctrine in Buddhism differentiates between two levels of truth in Buddhist discourse, a "relative", or commonsense truth (Tibetan: kun-rdzob bden-pa; Sanskrit: samvrtisatya), and an "ultimate" or absolute spiritual truth (Tibetan: don-dam bden-pa; Sanskrit: paramarthasatya). Stated differently, the Two Truths Doctrine holds that truth exists in conventional and ultimate forms, and that both forms are co-existent. Other schools, such as Dzogchen, hold that the Two Truths Doctrine are ultimately resolved into nonduality as a lived experience and are non-different. The doctrine is an especially important element of Buddhism and was first expressed in complete modern form by Nagarjuna, who based it on the Kaccāyanagotta Sutta.

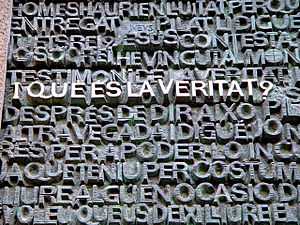

Christianity

Christian truth is based upon the history, revelation and testimony from the Bible, and are central to Christian beliefs. Some Christians believe that other authorities are sources of doctrinal truth — such as in Roman Catholicism, the Pope is said to be infallible when pronouncing on certain, rather specific, matters of church doctrine.[2] The central person in Christianity, Jesus, claimed to be Truth when he said, "I am the Way and the Truth and the Life; no one comes to the Father but through me."[3] Truth is thus considered to be an attribute of God. In Christian Science, (not recognised as a Christian organization by the bulk of mainstream churches) Truth is God.[4] Christian philosopher William Lane Craig notes that the Bible typically uses the words true or truth in non-philosophical senses to indicate such qualities as fidelity, moral rectitude, and reality. However, it does sometimes use the word in the philosophical sense of veracity.[5]

Biblical inerrancy

Some Christian traditions hold a doctrine called Biblical inerrancy, which believes that the Bible is without error. Various interpretations have been applied, depending on the tradition.[6][7] According to some interpretations of the doctrine, all of the Bible is without error, i.e., is to be taken as true, no matter what the issue. Other interpretations hold that the Bible is always true on important matters of faith, while other interpretations hold that the Bible is true but must be specifically interpreted in the context of the language, culture and time that relevant passages were written.[8]

The Magisterium of the Church

The Roman Catholic Church holds that it has a continuous teaching authority, magisterium, which preserves the definitive, i.e. the truthful, understanding of the faith, irrelevant of a literal interpretation of the Bible. The notion of the Pope as "infallible" in matters of faith and morals is derived from this idea.

Double truth theories

In thirteenth century Europe, the Roman Catholic Church denounced what it described as theories of double truth, i.e. theories to the effect that that reason and science can come to one truth and faith to another, with both being true yet contradictory. The Church held that there is only one truth, and that both faith and reason are two paths that lead to this one truth, making them complementary instead of antagonistic. This theological thought created a dogma largely responsible for the condemnation of some of the greatest scientific thinkers in history, including the Galileo affair almost 400 years later, and was still so entrenched in Christian thought almost another 400 years later that it was not until 1992 that Galileo was finally pardoned to the chagrin of Cardinal Ratzinger before becoming Pope Benedict XVI. [9]

Hinduism

Truthfulness is the ninth of the ten attributes of dharma. Generally, truthfulness relates to speech: to speak only what one has seen, heard or understood, however the essence of truthfulness is far deeper in Hinduism: it is defined as upholding the central concept of righteousness.[10] In the Upanishads of ancient India, truth is Sat (pronounced Sah't), the One Reality and Existence, which is directly experienced when the vision is cleared of dross. The Rishi discovers what exists, Sat, as the truth of one's own Being, the Self or Atma, and as the truth of the Being of God, Ishvara. In this usage, the term truth is used to refer to not merely a derived quality "true rather than false", but the true state of being, truth as what really is there. This is described by Ramana Maharshi: "There is no greater mystery than that we keep seeking reality though, in fact, we are reality."

Gaudiya Vaishnavism

In Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Krishna is Supreme Personality of Godhead. This is precisely described in natural commentary on Vedanta-sutra by Srila Vyasadeva - in Srimad-Bhagavatam. Absolute Truth is realized in three stages - as Brahman, Paramatma and Bhagavan, Supreme Personality of Godhead, Krishna.

Jainism

Although, historically, Jain authors have adopted different views on truth, the most prevalent is the system of anekantavada or "not-one-sidedness". This idea of truth is rooted in the notion that there is one truth, but only enlightened beings can perceive it in its entirety; unenlightened beings perceive only one side of the truth (ekanta). Anekantavada works around the limitations of a one-sided view of truth by proposing multiple vantage points (nayas) from which truth can be viewed (cf. Nayavāda). Recognizing that there are multiple possible truths about any particular thing, even mutually exclusive truths, Jain philosophers developed a system for synthesizing these various claims, known as syadvada. Within the system of syadvada, each truth is qualified to its particular view-point; that is "in a certain way", one claim or another or both may be true.

Judaism

There is no unilateral agreement among the different denominations of Judaism concerning truth. In Orthodox Judaism, truth is the revealed word of God, as found in the Hebrew Bible, and to a lesser extent, in the words of the sages of the Talmud. For Hasidic Jews truth is also found in the pronouncements of their rebbe, or spiritual leader, who is believed to possess divine inspiration.[11] Kotzk, a Polish Hasidic sect, was known for their obsession with truth.

In Conservative Judaism, truth is not defined as literally as it is among the Orthodox. While Conservative Judaism acknowledges the truth of the Tanakh, generally, it does not accord that status to every single statement or word contained therein, as do the Orthodox. Moreover, unlike Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism believes that the nature of truth can vary from generation to generation, depending on circumstances. For instance, with respect to halakha, or Jewish law, Conservative Judaism believes that it can be modified or adapted depending on the needs of the people. In Orthodox Judaism, by contrast, the halakha is fixed (by the sages of the Talmud and later authorities); the present-day task, therefore, is to interpret the halakha, but not to change it.

Reform Judaism takes a much more liberal approach to truth. It does not hold that truth is found only in the Tanakh; rather, there are kernels of truth to be found in practically every religious tradition. Moreover, its attitude towards the Tanakh is, at best, a document parts of which may have been inspired, but with no particular monopoly on truth, or in any way legally binding.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Collected Discourses of the Buddha: A new translation of the Samyutta Nikaya, Bhikkhu Bodhi, 2000

- ↑ See, e.g., Richard F. Costigan, The Consensus Of The Church And Papal Infallibility: A Study In The Background Of Vatican I (2005)

- ↑ See, e.g. Bible: John 14:6

- ↑ Truth - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

- ↑ Craig, William Lane. "Are There Objective Truths about God?". Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ↑ See, e.g. Norman L. Geisler, Inerrancy (1980)

- ↑ Stephen T. Davis, The debate about the Bible: Inerrancy versus infallibility (1977)

- ↑ See, e.g. Marcus J. Borg, Reading the Bible Again For the First Time: Taking the Bible Seriously But Not Literally (2002) 7-8

- ↑ Ratzinger, Joseph Cardinal (1994). Turning point for Europe? The Church in the Modern World—Assessment and Forecast. translated from the 1991 German edition by Brian McNeil. San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-461-8. OCLC 60292876.

- ↑ Truth Alone Will Triumph, Akhand-Jyoti.org

- ↑ Relationship of chasidim to their rebbe