Religion in ancient Tamil country

The Sangam period of Tamizhagam (c. 200 BCE to 200 CE) was characterized by the co-existence of many religions: Brahminism, Buddhism and Jainism alongside native Dravidian worship. The monarchs of the time practiced religious tolerance and openly encouraged religious discussions and invited teachers of every sect to the public halls to preach their doctrines.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| History of Tamil Nadu |

|---|

|

|

Main |

|

Medieval history

|

Tamil Religion

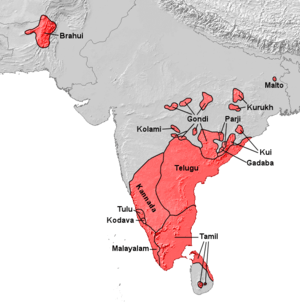

The term Tamil religions denotes the religious traditions and practices of Tamil-speaking people. Most Tamils originated and continue to live in India's southernmost area, now known as the state of Tamil Nadu; however, millions of Tamils have migrated to other parts of India, especially to its large cities, as well as abroad, particularly to Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Madagascar, Australia, Great Britain and, more recently, to the United States and Canada. Many emigrant Tamils retain elements of a cultural, linguistic, and religious tradition that predates the Christian era and has experienced a complex interaction of influences from kumari kandam civilization and Indus Valley Civilization [2] sources. At its apex between the eighth and fifteenth centuries, the Tamil region was the major center of Hindu civilization and, indeed, one of the major centers of civilization in the world. Today, while most Tamils remain essentially religion in pre Hindu (Tamil Religion), Hindu, some Tamils have embraced elements of Islam, Christianity and other religion.

Early Tamil Religion

A Neolithic cattle-herding culture existed in South India several millennia prior to the Christian era. By the first century, a relatively well-developed civilization had emerged, still largely pre-Hindu and only marginally sanskritized. It is described in some detail in Tamil texts such as the Tolkappiyam (a grammar written around the start before the Christian era) and by the "Cankam" poets—an "academy" of poets who wrote in the first two centuries ce. This culture was essentially Tamil civilization in nature.

The origins of the Dravidians are still a matter of dispute, but the South Indian culture the religious life of the Tamil civilization of Cankam times gave evidence of no significant mythological or philosophical speculation nor of any sense of transcendence in a bifurcated universe. Rather, it was oriented by a fundamental veneration of land and a sense of the celebration of individual life. Colorful flora and fauna were extolled and ascribed a symbolic significance that bordered on the sacred; for example, peacocks, elephants, and the blossoms of various trees were used as images for the basic realities of individual and cosmos. Earth's color and fertility were affirmed. Indigenous deities were venerated in field and hill, reflecting the attributes of the people in that zone and presiding over functions typical to their respective areas; thus, the Tamil god Murugan presided over hill and hunt and battled the malevolent forces of the hills, while Vēntaṉ oversaw the pastoral region and afforded it rain.

The early character of Tamil religion, in sum, was celebrative and relatively "democratic." It embodied an aura of sacral immanence, sensing the sacred in the vegetation, fertility, and color of the land. The summum bonum of the religious experience was expressed in terms of possession by the god, or ecstasy. Into this milieu there immigrated a sobering influence—a growing number of Jain and Buddhist communities and an increasing influx of brahmans and other northerners.

The Hinduization of Tamil Country Beginning in the third century ce, migrating brahmans and other persons influenced by Vedic and epic traditions were also becoming a part of the Tamil landscape. In the early cities, chieftains who sought to enhance their status employed brahman priests to perform Vedic rituals as had been the case in the north during the epic period. It was in the seventh century, however, that Hindu Sanskritic culture and religion merged with the indigenous Tamil society, leading to a pervasive hinduization of Tamil country and the emergence of a new and creative Hindu civilization.

The first significant feature of the "Hindu age" in Tamil India was the rise of devotional poetry "bhakti" in the vernacular language during the seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries. …

Prehistory

During the megalithic period of about 1000 BCE – 400 BCE, people of South India including Tamilagam, shared many beliefs and practices of the native Dravidian religion with the megalithic builders elsewhere in the Indian subcontinent and beyond.[2] The famous 3.5 metre-high granite figure excavated at Mottur, in present-day Vellore district, is considered the oldest known anthropomorphic representation of God in stone in the Tamil country.[3] Some form of Mother Goddess worship was prevalent in the megalithic period, as suggested by the discovery of a copper image of a Goddess in the urn-burials of Adichanallur and other excavations in Tamil Nadu that have yielded headstones, shaped like the seated Mother.[4] Megalithic culture attached great importance to the cult of the dead and ancestors. Certain gods in the Hindu pantheon, such as Cheyon (Murugan/ Karthikeya), Maayon (Thirumal / Vishnu), Korravai (Durga) and Naga, Aiyanar (or Sastha), deities were originally tribal gods of this period.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

History

|

|

Culture

|

|

Language

|

|

Religion

|

|

Regions

|

|

People

|

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

Divinity of Kings

Pre-Sangam and Sangam age

In many parts of Nilagiri mountain ranges people tribal community people Todas, Kotas and Badagas had slightly different set of religious practices and beliefs . Their religion centres on the buffalo; consequently, rituals are performed for all dairy activities as well as for the ordination of dairymen-priests. The religious and funerary rites provide the social context in which complex poetic songs about the cult of the buffalo are composed and chanted. In general throughout Tamil Nadu like the rest of the regions in India, a king is considered to be divine by nature and possess religious significance.[5] The king is 'the representative of God on earth' and lives in a palace called ' Koyil', which means the residence of God. The ritual worship of God was also given to the king.[6][7]

Modern words for god like ko (Tamil:கோ), irai (Tamil:இறை), āṇḍavar (Tamil:ஆண்டவன்) originally meant King, Emperor, and Conqueror respectively before being used to refer to God. The Modern Tamil word for temple, koyil (Tamil:கோயில்), literally means king's house, or palace. Mōcikīraṉār in the Purananuru says:

| “ | only the King is the life-breath of a kingdom. |

” |

The Kingdom suffered by famine or disorder when the King erred.[8] These elements were incorporated later into Hinduism like the legendary marriage of Shiva to Queen Mīnātchi who ruled Madurai or Wanji-ko, an Old Tamil God who later merged into Indra.[9] Tolkappiyar refers to the Three Crowned Kings as the "Three Glorified by Heaven", (Tamil: வாண்புகழ் மூவர், Vāṉpukaḻ Mūvar ?).[10] In the Dravidian-speaking South, the concept of divine kingship led to the assumption of major roles by state and temple.[11]

Middle ages

At the birth of Rajaraja Chola I, the Thiruvalangadu inscription states:

"Having noticed by the marks (on his body) that Arulmozhi was the very Vishnu, the protector of the three worlds."

During the Bhakti movement poets often compared Gods to Kings.[12]

Native Dravidian religion

Dravidian religion was actively separate during the Sangam period. It was only after the 5th century that the indigenous Dravidian religion completely fused with Vedic religion.[13] Remnants of the practice still continue in rural areas. The cult of the mother goddess is treated as an indication of a society which venerated femininity. This mother goddess was conceived as a virgin, one who has given birth to all and one.[14] The temples of the Sangam days, mainly of Madurai, seem to have had priestesses to the deity, which also appear predominantly a goddess.[15] In the Sangam literature, there is an elaborate description of the rites performed by the Kurava priestess in the shrine Palamutircholai.[16]

Veriyattam

This refers to possession of women. They took part in priestly functions. Under the influence of the god, they sang and danced, but also read the dim past, predicted the future, diagnosed diseases.[17] Twenty two poets of the Sangam age in as many as 40 poems portray Veriyatal. Velan is a ëreporter and prophetí endowed with supernatural powers. Veriyatal had been performed by men as well as women.[18]

Nadukkal

Among the early Tamils the practice of erecting memorial stones (Nadukal) had appeared, and it continued for quite a long time after the Sangam age, down to about 11th century.[19] It was customery for people who sought victory in war to worship the hero-stones to bless them with victory.[20]

Hinduism

During the Sangam age, Hinduism, including Vedic Brahminism, was a popular religion among the people. Siva, Murugan, Krishna, Balarama and Kali were some of the popular deities among the Hindus. The division of the Sangam landscape into five regions, is also apparent in religion – with each region having had its own patron deity.[21] The people of the Kurinji or the mountainous regions worshipped Muruga, the god of war. He was portrayed as having six faces and twelve arms. His shrines were usually on the peaks of high hills or in the midst of dense forests. He carried a lance as his weapon and hence was called Velan or lancer. Animal sacrifices were carried out under sheds that were put up for the purpose, with flags hoisted over them that bore the emblem of Muruga, the rooster. Ancient mythology has it that Muruga was the commander-in-chief of the celestial army when it fought the Asuras or the demons. According to the tradition of the Kuravas, the hill people, Muruga married a maiden of their tribe.

The people of the pastoral lands or the Mullai regions worshipped Krishna and his brother Balarama. The shepherd races of these regions amused themselves by enacting plays that portrayed the main events of Krishna’s mythical life, such as his childhood pranks, his victory against the evil Kamsa, his embassy to Duryodhana and other episodes involving him in the Mahabaratha. Krishna was also popularly known as Mayavan or Mayon, the deceiver. Balarama his elder brother was believed to have extraordinary physical strength. The Marutham people(Mallar/pallar) worshipped Indra or Ventan, while the Neithal people considered Varunan or Katalon to be their patron deity and the Palai people worshipped Korravai or Kali. Among the higher classes of the Tamil society, the favorite deity was Siva. He was portrayed as a man of fair complexion with tangled locks of red hair and three eyes, the third one situated in the middle of his forehead. He wore tiger’s skin and rode a bullock, armed with a battle-axe and the trishul. The temples of Siva were considered the most stately and august of the public edifices.[22] Other popular deities of this age were Kama the god of love, Surya the sun, Chandra the moon and Yama the god of death. The Brahmins of the Tamil country attached great importance to the performance of Yagas or Vedic sacrifices. Priests, learned in the Vedic rites, performed these sacrifices usually under the patronage of the kings.[23]

The temples of the Sangam age were built out of perishable materials such as plaster, timber and brick, which is why little trace of them is found today.[24] The only public structures of any historical importance belonging to this age that have survived to this day are the rock-beds hewn out of natural rock formation, that were made for the ascetics. The Cilapatikaram and the Sangam poems such as Kaliththokai, Mullaippattu and Purananuru mention several kinds of temples such as the Puranilaikkottam or the temple at the outskirts of a city, the Netunilaikkottam or the tall temple, the Palkunrakkottam the temple on top of a hill, the Ilavantikaippalli or the temple with a garden and bathing ghat, the Elunilaimatam or a seven storeyed temple, the Katavutkatinakar or the temple city.[25]

Some of the popular festivals of this age were Karthigaideepam, Tiruvonam, Kaman vizha and Indira vizha. Karthigaideepam was otherwise known as Peruvizha and was celebrated in the Tamil month of Karthigai every year.Tiruvonam was celebrated in the month of Avani to denote the birth of Mayon. The Kaaman vizha was held in the spring and during this festival, men and women dressed up well and participated in dancing. Indravizha included the performance of Vedic sacrifices, prayers to various gods, musical recitals and dancing.[26]

Jainism

The exact origins of Jainism in Tamil Nadu is unclear. However, Jains flourished in Tamil Nadu at least as early as the Sangam period. Tamil Jain tradition places their origins are much earlier. The Ramayana mentions that Rama paid homage to Jaina monks living in South India on his way to Sri Lanka.[27] Some scholars believe that the author of the oldest extant work of literature in Tamil (3rd century BCE), Tolkāppiyam, was a Jain.[28]

A number of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have been found in Tamil Nadu that date from the 2nd century BCE. They are regarded to be associated with Jain monks and lay devotees.[29][30]

Tirukkural by Valluvar is considered to be the work by a Jain by scholars like V. Kalyanasundarnar, Vaiyapuri Pillai,[31] Swaminatha Iyer,[32] P.S. Sundaram.[33] It emphatically supports vegetarianism (Chapter 26) and states that giving up animal sacrifice is worth more than thousand offerings in fire( verse (259).

Silappatikaram, first epic in Tamil literature, was written by a Camaṇa, Ilango Adigal. This epic is a major work in Tamil literature, describing the historical events of its time and also of then-prevailing religions, Jainism, Buddhism and Shaivism. The main characters of this work, Kannagi and Kovalan, who have a divine status among Tamils, were Jains.

According to George L. Hart, who holds the endowed Chair in Tamil Studies by University of California, Berkeley, has written that the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies: was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai:

There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 AD in Maturai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the cangkam legend."[34]

Jainism began to decline around the 8th century, with many Tamil kings embracing Hindu religions, especially Shaivism. Still, the Chalukya, Pallava and Pandya dynasties embraced Jainism.

Buddhism

The Buddhists worshiped the impressions of Buddha’s feet engraved on stone and platforms made of stone that represented his seat. The pious Buddhist walked round them, with his right side towards them and bowed his head as a token of reverence.[35] The Cilapatikaram mentions that the monks worshipped Buddha by praising him as the wise, holy and virtuous teacher who adhered to his vows strictly, as the one who subdued anger and all evil passions and as the refuge of all mankind. In the Buddhist Viharas or monasteries, learned monks preached their sermons, seated in a place which was entirely concealed from the view of the audience. The Buddhists did not observe the distinctions of caste and invited all ranks to assemble on a footing of equality. Self-control, wisdom and charity were among the virtues preached and practiced by the monks, who were numerous in the ancient Tamil country.[1]

Christianity

Christianity was introduced in India by St. Thomas the Apostle who landed at Muziris on Malabar Coast in the year 52 AD. These ancient Christians are today known as Saint Thomas Christians or Syrian Christians or Nasrani.[36][37][38] They are now divided into different denominations namely, Syro-Malabar Catholic, Syro-Malankara Catholic, Malankara Orthodox, Jacobite and Malankara Marthoma. Syrian Christians followed the same rules of caste and population as that of Hindus and sometimes they were even considered as population neutralizers.[39][40] They tend to be endogamous, and tend not to intermarry even with other Christian groupings. Saint Thomas Christians derive status within the caste system from the tradition that they were elites, who were evangelized by St. Thomas.[41][41][42][43] Also, internal mobility is allowed among these Saint Thomas Christian sects and the caste status is kept even if the sect allegiance is switched (for example, from Syrian Orthodox to Syro-Malabar Catholic).[44] Despite the sectarian differences, Syrian Christians share a common social status within the Caste system of Kerala and is considered as Forward Caste.[43]

Judaism

The traditional account is that traders from Judea arrived in the city of Cochin, Kerala (then Chera Nadu), in 562 BC, and that more Jews came as exiles from Israel in the year 70 CE after the destruction of the Second Temple.[45] The distinct Jewish community was called Anjuvannam. The still-functioning synagogue in Mattancherry belongs to the Paradesi Jews, the descendants of Sephardim that were expelled from Spain in 1492.[45]

Philosophies of religion

Secularism

The secular identity[46] of the Cankam literature is often celebrated to represent the tolerance among Tamil people. Es Vaiyāpurip Piḷḷai, concludes in his History of Tamil language and literature: beginning to 1000 A. D.:[47]

| “ | |

” |

| —Es Vaiyāpurip Piḷḷai, History of Tamil language and literature: beginning to 1000 A. D. | ||

Most scholars agree that the lack of 'god' should not be inferred to be atheistic. The Tamil books of Law, particularly the Tirukkural, is considered as the Perennial philosophy of Tamil culture because of its universalisability.

Ūzh and Vinai

Ūzh meaning 'fate' or 'destiny' and vinai meaning 'works' concerns the ancient Tamil belief of differentiating what man can do and what is destined.[48]

Kaṭavuḷ and Iyavuḷ

Sangam Tamil people understood two distinct characteristics of Godhood. God who is beyond all (Tamil: கடவுள், Kaṭavuḷ ?) and the God who sets things in motion (Tamil: இயவுள், Iyavuḷ ?).[49]

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

|

Ancient Era |

|

Middle Ages

|

|

Colonial

|

|

Post independence

|

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kanakasabhai. p. 233. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Vedic Roots of Early Tamil Culture by Michael Danino". Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ↑ Narasimhaiah, B (2004). Neolithic and Megalithic Cultures in Tamil Nadu. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 203. ISBN 81-7574-048-5.

- ↑ Raman, K.V (2002). "Sakti Cult in Tamil Nadu – a Historical Perspective". Proceedings of the 9th session of Indian Art History Congress. Hyderabad: Sundeep Prakashan, New Delhi. pp. ch. 19.

- ↑ Harman, William P. (1992). The sacred marriage of a Hindu goddess. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 6.

- ↑ Anand, Mulk Raj (1980). Splendours of Tamil Nadu. Marg Publications.

- ↑ Chopra, Pran Nath (1979). History of South India. S. Chand.

- ↑ A.K., Ramanujan (2011). Poems of Love and War: From the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems of Classical Tamil. Columbia University Press. p. 287.

- ↑ Bate, Bernard (2009). Tamil oratory and the Dravidian aesthetic: democratic practice in south India. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ A. Kiruṭṭin̲an̲ (2000). Tamil culture: religion, culture, and literature. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. p. 17.

- ↑ Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history: Volume 1. Scribner. ISBN 9780684188980.

- ↑ Hopkins, Steven (2002). Singing the body of God: the hymns of Vedāntadeśika in their South Indian tradition. Oxford University Press. p. 113.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, Haridas (1978). The Cultural Heritage of India: Languages and literatures. Ramakrishna Mission, Institute of Culture.

- ↑ Thiruchandran, Selvy (1997). Ideology, caste, class, and gender. Vikas Pub. House.

- ↑ Manickam, Valliappa Subramaniam (1968). A glimpse of Tamilology. Academy of Tamil Scholars of Tamil Nadu. p. 75.

- ↑ Lal, Mohan (2006). The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume Five (Sasay To Zorgot), Volume 5. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4396. ISBN 8126012218.

- ↑ Iyengar, Srinivasa (1929). History of the Tamils: from the earliest times to 600 A.D. Asian Educational Services. p. 77.

- ↑ Music as History in TamilNadu. Primus Books. 2010. p. 16. ISBN 9380607067.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Shashi, S. S. (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh: Volume 100. Anmol Publications.

- ↑ Subramanium, N. (1980). Śaṅgam polity: the administration and social life of the Śaṅgam Tamils. Ennes Publications.

- ↑ Subrahmanian. p. 381. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Kanakasabhai. p. 230. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Kanakasabhai. p. 231. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Subrahmanian. p. 382. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Gopalakrishnan. p. 19. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Balambal. p. 6. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://jainsquare.com/2011/07/29/history-of-tamil-jains/|date=September 2011

- ↑ Singh, Narendra (2001). Encyclopaedia of Jainism. Anmol Publications. p. 3144. ISBN 978-81-261-0691-2.

- ↑ Early Tamil epigraphy from the earliest times to the sixth century A.D. Iravatham Mahadeva, Harvard University Press, 2003

- ↑ http://jainsamaj.org/rpg_site/literature2.php?id=595&cat=42 RECENT DISCOVERIES OF JAINA CAVE INSCRIPTIONS IN TAMILNADU By Iravatham Mahadevan

- ↑ Tirukkural, Vol. 1, S.M. Diaz, Ramanatha Adigalar Foundation, 2000,

- ↑ Tiruvalluvar and his Tirukkural, Bharatiya Jnanapith, 1987

- ↑ The Kural, P. S. Sundaram, Penguin Classics, 1987

- ↑ The Milieu of the Ancient Tamil Poems, Prof. George Hart

- ↑ Kanakasabhai. p. 232. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies, Volume 18. Institute of Asian Studies (Madras, India). 2000.

- ↑ Weil S. 1982; Jessay P.M. 1986; Menachery 1973; Menachery 1998.

- ↑ A. E. Medlycott, India and The Apostle Thomas, pp.1–71, 213–97; M. R. James, Apocryphal New Testament, pp.364–436; Eusebius, History, chapter 4:30; J. N. Farquhar, The Apostle Thomas in North India, chapter 4:30; V. A. Smith, Early History of India, p.235; L. W. Brown, The Indian Christians of St. Thomas, p.49-59.

- ↑ Vadakkekara, Benedict (2007). Origin of Christianity in India: a Historiographical Critique, pp. 325–330. Media House Delhi.

- ↑ Fuller, Christopher J. (March 1976). "Kerala Christians and the Caste System". Man. New Series (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 11 (1): 55–56.(subscription required)

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Fuller, Christopher J. (March 1976). "Kerala Christians and the Caste System". Man. New Series (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 11 (1): 55, 68.(subscription required)

- ↑ Fuller, C.J. "Indian Christians: Pollution and Origins." Man. New Series, Vol. 12, No. 3/4. (Dec., 1977), pp. 528–529.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Forrester, Duncan (1980). Caste and Christianity. Curzon Press. pp. 98,102.

- ↑ Fuller, Christopher J. (March 1976). "Kerala Christians and the Caste System". Man. New Series (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 11 (1): 61.(subscription required)

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 P. 125 The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia By Mordecai Schreiber

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Tamil Literature: Introductory articles. Institute of Asian Studies. 1990.

- ↑ Piḷḷai, Es Vaiyāpurip (1956). History of Tamil language and literature: beginning to 1000 A. D. New Century Book House.

- ↑ Journal of Tamil studies, Issues 31–32. International Association of Tamil Research. 1987.

- ↑ Singam, S. Durai Raja (1974). Ananda Coomaraswamy: remembering and remembering again and again. Raja Singam. p. 50.

References

- Balambal, V (1998). Studies in the History of the Sangam Age. Kalinga Publications, Delhi.

- Gopalakrishnan, S (2005). Early Pandyan Iconometry. Sharada Publishing house, New Delhi.

- Kanakasabhai, V (1904). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. Asian Educational Services, New Delhi.

- Jackson, A.V. Williams (1906). History of India. The Grolier Society, London.

- Subrahmanian, N (1972). History of Tamilnad. Koodal Publishers, Madurai.