Reichskommissariat Moskowien

| Reichskommissariat Moskowien | ||||||

| Projected Reichskommissariat of Germany | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Capital | initially Moscow, then not designated | |||||

| Government | Civil administration | |||||

| Reichskommissar | Siegfried Kasche (projected) | |||||

| Historical era | World War II | |||||

| - | Established | N/A | ||||

| - | Disestablished | N/A | ||||

Reichskommissariat Moskowien (also rendered as Moskau, abbreviated as RKM; Russian: Рейхскомиссариат Московия), literally "Reich Commissariat of Muscovy (or Moscow)", was the civilian occupation regime that Nazi Germany intended to create in central and northern European Russia during World War II, one of several similar Reichskommissariate. It was also known initially as the Reichskommissariat Russland (Reich Commissariat of Russia). Siegfried Kasche was the projected Reichskomissar, but due to the German failure to occupy the territories intended to form the Reichskommissariat, it remained on paper only.

Background

The German Nazis intended to destroy Russia permanently, irrespective of whether it was capitalist, communist or tsarist. Adolf Hitler's Lebensraum policy, expressed in Mein Kampf, was to dispossess the Russian inhabitants – as was to happen with other Slavs in Poland and most of Eastern Europe- and to either expel most of them beyond the Ural mountains or to exterminate them by various means. German colonial settlement was to be encouraged (Generalplan Ost).

As the campaign against the Soviet Union advanced eastward, the occupied territories would gradually be transferred from military to civilian administration. Hitler's final decision on its administration entailed the new eastern territories being divided into four Reichskommissariate in order to destroy Russia as a geographical entity by dividing it into as many different parts as possible. These new institutions were to be under the nominal supervision of Reichsleiter Alfred Rosenberg as head of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (Reichsministerium für die besetzten Ostgebiete). The leaders of these provinces, the Reichskommissars, would however be direct subordinates of Hitler himself, and answerable only to him. Conquered territories of most of Russia proper were initially to become a Reichskommissariat Russland (Reich commissariat of Russia) according to Rosenberg's plans, although this was later changed to Moskowien (Muscovy) informally also known as Moskau (Moscow). These eastern districts were thought to be the most sensitive to administer of the conquered territories. As a consequence, they would be managed from the regional capitals and directly by the German government in Berlin.

The plans were ultimately never fulfilled. The German military operation to capture Moscow and central Russia (Fall Taifun) failed and marked the high-water point of German success in the region. The transfer of conquered territories to Nazi civilian rule was therefore never completed.

Territorial planning

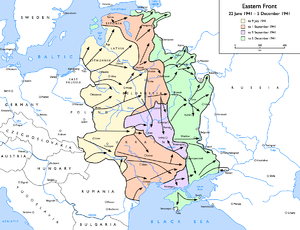

The envisioned province included most of European Russia between the Ural mountains (as well as some districts east of it, including the city of Sverdlovsk) and its boundaries with Finland, the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine. The Russian parts of the Caucasus region were to be controlled by a separate Reichskommissariat Kaukasus, while the rest of southern Russia was to be integrated into the Reichskommissariat Ukraine for its intended extension eastward to the border with Kazakhstan. Smaller parts that were excluded were the Pskov, Smolensk and Leningrad areas (included in the Reichskommissariat Ostland), and Eastern Karelia and the Kola peninsula, which were promised to Germany's co-belligerent Finland in 1941 for its contribution to the campaign in the east. It would therefore encompass more or less the same lands that were once under the control of the mediaeval state of Muscovy. Its final territory was to be bounded on the west by the Reichskommissariat Ostland and the border with Finland, on the north by the Arctic ocean, in the east by the Ural Mountains and Ural River, and in the south by the massively expanded Reichskommissariat Ukraine.

The planned administrative subdivisions of the province were largely based boundary-wise on the pre-existing Russian oblasts, and supposed to be seated in Leningrad, Gorki, Tula, Moscow, Kazan, Kirov, Molotov, and Ufa.

The administrative capital was tentatively proposed as Moscow, the historical and political center of the Russian state. As the German armies were approaching Moscow during the 1941 campaign however, Hitler determined that Moscow, like Leningrad and Kiev, would be levelled and its 4 million inhabitants killed to destroy it as a potential center of Bolshevist resistance. For this purpose Moscow was to be covered by a large artificial lake which would permanently submerge it,[1][2] by opening the sluices of the Moscow-Volga Canal.[3] During the advance on Moscow Otto Skorzeny was tasked with capturing these dam structures.[3]

During a conference on 16 July 1941, Hitler stated his personal desires on the division of the eastern territories to be acquired for Germany.[4] The Crimean peninsula, together with a large hinterland to its north encompassing much of the southern Ukraine was to be "cleared" of all existing foreigners and exclusively settled by Germans, becoming Reich territory (part of Germany).[4] The formerly Austrian part of Galicia was to be treated in a similar fashion. In addition the Baltic states, the "Volga colony" and the Baku district (as a military concession) would also have to be annexed to the Reich.[4]

At first, the plans had assumed an eastern limit at the "A-A line", a notional boundary running along the Volga river between the two cities of Archangelsk and Astrakhan. Since it was expected well-ahead of the operation that the Soviet Union would in all likelihood not be totally defeated by military means despite being reduced to a rump state, aerial bombardments were to be carried out — despite the near-total lack of a strategic bomber design in the Luftwaffe's arsenal with which to perform such raids — against the remaining enemy industrial centers further to the east.

Political leadership

Rosenberg had initially proposed Erich Koch, notorious even among the Nazis as a particularly brutal leader,[5] as Reichskommissar of the province on 7 April 1941.[6]

This occupation will indeed have a completely different character to that in the Baltic Sea provinces, in the Ukraine and in the Caucasus.[nb 1] It will be geared towards the oppression of any Russian or Bolshevist resistance and [sic] requires an absolutely ruthless personality, not only on the part of the military representation but also the potential political leadership. The resulting tasks need not be recorded.—Alfred Rosenberg, memo dated 7 April 1941[6]

Koch rejected his nomination in June of that year because it was, as he described it, "entirely negative", and was later given control of Reichskommissariat Ukraine instead.[5] Hitler proposed Wilhelm Kube as an alternative, but this was rejected after Hermann Göring and Rosenberg deemed him too old for the position (Kube was then in his mid-fifties), and instead assigned him to Belarus. SA-Obergruppenführer Siegfried Kasche, the German envoy in Zagreb, was selected instead.[7] Hamburg senator and SA General Wilhelm von Allwörden promoted himself to be nominated as the Commissioner for Economic Affairs for the Moscow area.[8] Kasche's nomination was opposed by Heinrich Himmler, who considered Kasche's SA background as being a problem and characterized him to Rosenberg as "a man of the desk, in no wise energetic or strong, and an outspoken enemy of the SS".[9]

Erich von dem Bach-Zalewski was to become the regional Higher SS and Police Leader, and was already assigned to Army Group Centre as HSSPF-Russland-Mitte (Central Russia) for this purpose.[5] Odilo Globocnik, then the SS and Police Leader in Lublin was to head Generalkommissariat Sverdlovsk, the easternmost district of Moskowien.[5] Rosenberg suggested Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf as Hauptkommissar of the Yaroslavl district.[10]

Planned policies

See also

- Russian volunteer units with Axis forces

- Battle of Moscow

- Lokot Autonomy

Notes

- ↑ Note that this comment needs to be read in the context of Rosenberg's rejected plan to make use of the Soviet Union's non-Russian ethnic groups in these regions (Balts, Ukrainians, et al) by presenting the German invasion as a liberation from Russian rule and promising them political independence.

References

- ↑ Oscar Pinkus (2005). The war aims and strategies of Adolf Hitler, p. 228. MacFarland & Company Inc. Publishers.

- ↑ Fabian Von Schlabrendorff (1947). They Almost Killed Hitler: Based on the Personal Account of Fabian Von Schlabrendorf, p. 35. Gero v. S. Gaevernitz.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ganzenmüller, Jörg (18 July 2011). Blockade Leningrads: Hunger als Waffe. Zeit Online. Retrieved 6 November 2011. (In German)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Martin Bormann's Minutes of a Meeting at Hitler’s Headquarters (July 16, 1941). German History in Documents and Images. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kay (2006), p. 88.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kay, Alex J. (2006). Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder: Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940-1941, p. 79. Berghahn Books.

- ↑ Kay (2006), pp. 181-182.

- ↑ Angelika Ebbinghaus, Karsten Linne (1997). Kein abgeschlossenes Kapitel: Hamburg im "Dritten Reich". Europäische Verlagsanstalt. ISBN 3434520066. p. 79

- ↑ Dallin, Alexander (1981). German rule in Russia, 1941-1945: a study of occupation policies. Westview. p. 296

- ↑ (German) Gerlach, Christian (1999). Kalkulierte Morde. Hamburger Edition.

Sources

- Rich, Norman (1973). Hitler’s War Aims: Ideology, the Nazi State, and the Course of Expansion. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-05454-3.

- Rich, Norman (1974). Hitler’s War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393055-09-2.

- Wasser, Bruno (1993). Himmler's Raumplanung im Osten: Der Generalplan Ost in Polen 1940-1944. Basel: Birkhäuser. ISBN 3-540-30951-9.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter and Uberschär, Gerd. R. (2009). Hitler's War in the East: A Critical Assessment, 3rd Edition. New York: Berghan Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-501-9.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)