Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum

The Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum (or "Mauro-Roman kingdom" in English) was a Berber kingdom that existed in the Maghreb from the 4th century AD until the Arab conquest of North Africa.[1]

Characteristics

Emperor Diocletian reorganized the Roman Empire in AD 298 and later withdrew from the area of Volubilis, the Rif mountains in northern Morocco and the western Algerian Atlas mountains after the Crisis of the 3rd Century. Berber rulers created a small independent kingdom there, centered around the capital Altava and the fully Romanised city of Volubilis. From the 7th century Byzantine historians usually called it the "Kingdom of Altava".

This kingdom acted as a small Roman client state, but sometimes the Berber tribes living in that semi-free territory raided the Roman cities of the coast. This Mauro-Roman kingdom was never conquered by the Vandals, who destroyed the Roman presence in the Maghreb in AD 429-435.

The Western kingdom more distant from the Vandal kingdom was the one of Altava, a city located at the borders of Mauretania Tingitana and Caesariensis....It is clear that the Mauro-Roman kingdom of Altava was fully inside the Western Latin world, not only because of location but mainly because it adopted the military-religious-sociocultural-administrative organization of the Roman Empire...[2]

The Vandal kingdom allowed the creation of other Romano-Berber states at the borders, but fell a century later, conquered by the Byzantine empire, which established an African prefecture, and later the Exarchate of Carthage.

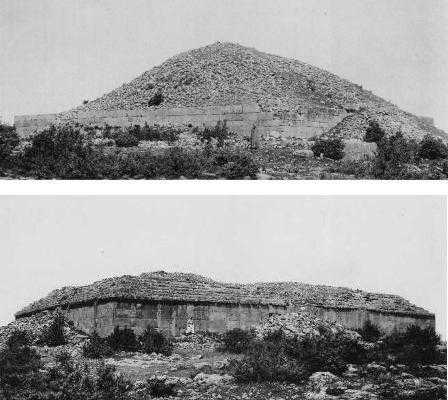

Since then there are few historical accounts of the Mauro-Roman kingdom. The extension of this "kingdom" is not well known, but common civilizational traits [3] suggest that 13 monumental burials in the region, called Djeddars, built up to nearly two centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, belong to the same entity.

During the 5th century the area was fully Christianized, according to historian Theodore Mommsen, and the kings were probably buried in a Djeddar near Frenda.[4] Indeed the historian Gabriel Camps [5] thinks that some Berber kings (like Masuna and Garmul) were buried in a Djeddar near Frenda (whose capital seems to have been called "Tsinouna", in his opinion). The inscriptions found in these graves do not go back beyond the 6th century. However, the researcher Adrien Berbrugger traces the construction of the Djeddar to a later period than the beginning of the Byzantine presence in the Maghreb.

According to historian Noé Villaverde the Mauro-Roman kingdom at the beginning of the 7th century was reduced to the Mediterranean area around Altava, while Volubilis become autonomous under the influence and protection of the Mauri kingdoms of the Atlas mountains.

The kingdom (now called the "Kingdom of Altava") interacted with the Byzantine Exarchate against the Muslim invasion in AD 650, and helped defeat the first Arab attacks in the Maghreb. It disappeared completely when the Arabs conquered the entire region around AD 708.

History

Mauretania and western Numidia were annexed by Rome in AD 40, and became a Roman province in AD 43. This was later enlarged under the names of Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis. But in the 4th century the Roman Empire lost an area on the current borders of Morocco and Algeria to the local Berber tribes.

Indeed Maximian (co-emperor with Diocletian) at the end of the 3rd century was able to focus on the conflict in Mauretania (North-west Africa).[6] As Roman authority weakened during the 3rd century, nomadic Berber tribes harassed settlements in the region, with increasingly severe consequences. In the year 289, the governor of Mauretania Caesariensis (roughly modern Algeria) gained a temporary respite by pitting a small army against the Berber tribes of the Bavares and Quinquegentiani, but the raiders soon returned. In 296, Maximian raised an army from Praetorian cohorts, Aquileian, Egyptian, and Danubian legionaries, Gallic and German auxiliaries, and Thracian recruits, advancing through Spain that autumn.[7] He may have defended the region against raiding Moors[8] before crossing the Strait of Gibraltar into Mauretania Tingitana (roughly modern Morocco) to protect the area from Frankish pirates.[9]

By March 297, Maximian had begun a bloody offensive against the Berbers. The campaign was lengthy, and Maximian spent the winter of 297–298 resting in Carthage before returning to the field.[10] Not content to drive them back into their homelands in the Atlas Mountains – from which they could continue to wage war – Maximian ventured deep into Berber territory. The terrain was unfavorable, and the Berbers were skilled at guerrilla warfare, but Maximian pressed on. Apparently wishing to inflict as much punishment as possible on the tribes, he devastated previously secure land, killed as many as he could, and drove the remainder back into the Sahara.[11] His campaign was concluded by the spring of AD 298.

At the beginning of the 4th century, parts of Roman Mauretania were reconquered by Berber tribes. Direct Roman rule became confined to a few coastal cities (such as Septum (Ceuta) in Mauretania Tingitana and Cherchell in Mauretania Caesariensis) by the late 3rd century.[12] Historical sources about inland areas are sparse, but these were apparently controlled by local Berber rulers who, however, maintained a degree of Roman culture, including the local cities, and usually nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Roman Emperors.[13] These Berber rulers were Christians and used Latin as their official language, while the Berber population spoke Latin in the cities such as Volubilis, but spoke the Berber language with many Latin words in the countryside.

One of these rulers, Masuna, described himself as Rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum ("King of the Roman and Moorish peoples"). Masuna is known only from an inscription on a fortification in Altava (modern Ouled Mimoun, in the region of Oran), dated 508, and he is known to have possessed Altava and at least two other cities, Castra Severiana and Safar, as mention is made of officials he appointed there.[14]

Altava was later the capital of another ruler, Garmul or Garmules, who resisted Byzantine rule in Africa but was finally defeated in 578.[15] Indeed, in the late 560s the Moorish king Garmul of the "Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum" launched raids into Roman territory, and although he failed to take any significant town, three successive generals (the praetorian prefect Theodore and the magister militum Theoctistus in AD 570, and Theoctistus' successor Amabilis in 571) are recorded by John of Biclaro to have been killed by Garmul's forces.[16] His activities, especially when considered together with the simultaneous Visigoth attacks in Spania, presented a clear threat to the province's authorities.

Garmul was not the leader of a mere semi-nomadic tribe, but of a fully-fledged barbarian kingdom, with a standing army. Thus the new emperor, Tiberius II Constantine, reappointed Thomas as praetorian prefect, and the able general Gennadius was posted as magister militum with the clear aim of reducing Garmul's kingdom. Preparations were lengthy and careful, but the campaign itself, launched in 577–78, was brief and effective, with Gennadius using terror tactics against Garmul's subjects. Garmul was defeated and killed by AD 579, and the coastal corridor between Tingitana and Caesariensis secured.[17]

The Byzantine historian Procopius also mentions another independent ruler, Mastigas, who controlled most of Mauretania Caesariensis in the 530s. But some historians argue that Mastigas and Masuna were the same king.[18]

Garmul was defeated and killed in 579. It is to him or one of the successors that we can assign the Djedar F that appears to be the oldest in Jebel Araoui, suggesting that the dynasty survived until the end of the seventh century and had to bear the brunt of the Arab conquest.[19]

After Garmul we have a period of relative peace, with the Byzantine maintaining a direct and indirect control on the Mediterranean coast of the Maghreb. This peace allowed a development of a strong economy even in the kingdom of Altava, where there was the creation of the Djeggar F of Araoui. But the arrival of the Arabs changed everything and around AD 708 the "Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum" was conquered and disappeared.[20] However initially the king Kusaila (probably ruler of the kingdom of Altava, according to historian Noé Villaverde) at the Battle of Vescera (modern Biskra in Algeria), was able to stop the Arab attacks. Indeed in this battle, that was fought in AD 682 between the Christian Berbers and their Byzantine allies from the Exarchate of Carthage against an Umayyad Arab army under Uqba ibn Nafi,[21] he was able to defeat the Arabs. These invasors were temporarily expelled from the area of modern Algeria and Tunisia for more than a decade.[22]

Volubilis: a Roman and Post-Roman history of a Mauro-Roman city

Volubilis was one of the main cities of the "Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum". According to Noe Villaverde Vega [23] it was part of this Mauro-roman kingdom from the end of Roman domination of the Volubilis area around AD 285, until the end of the 6th century.

Indeed the city became the administrative centre of the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana during the first century of the Roman Empire. It remained loyal to Rome despite a revolt in AD 40–44 led by one of Ptolemy's freedmen, Aedemon, and its inhabitants were rewarded with grants of citizenship and a ten-year exemption from taxes.[24] The city was raised to the status of a municipium and its system of governance was overhauled, with the Punic-style suffetes replaced by annually elected duumvirs, or pairs of magistrates.[25] However, the city's position was always tenuous; it was located on the south-eastern edge of the province, facing hostile and increasingly powerful Berber tribes. A ring of five forts located at the modern hamlets of Aïn Schkor, Bled el Gaada, Sidi Moussa, Sidi Said and Bled Takourart (ancient "Toscolosida") were constructed to bolster the city's defence.[24] Sidi Said was the base for the Cohors IV Gallorum equitata, an auxiliary cavalry unit from Gaul, while Aïn Schkor housed Spanish and Belgic cohorts. Sidi Moussa was the location of a cohort of Parthians, and Gallic and Syrian cavalry were based at Toscolosida.[26] Rising tensions in the region near the end of the 2nd century led the emperor Marcus Aurelius to order the construction of a 2.5 km (1.6 mi) circuit of walls with eight gates and 40 towers.[24] Volubilis was connected by road to Lixus and Tingis (modern Tangier) but had no eastwards connections with the neighbouring province of Mauretania Caesariensis, as the territory of the Berber Baquates tribe lay in between.[24]

Rome's control over the city ended following the chaos of the Crisis of the 3rd Century, when the empire nearly disintegrated as a series of generals seized and lost power through civil wars, palace coups and assassinations. Around 280, Roman rule collapsed in much of Mauretania and was never re-established. The collapse was evidently foreseen by the inhabitants of Volubilis, who buried coin hoards and fine bronze statues under their villas for safekeeping, where they were eventually rediscovered by archaeologists nearly 1,700 years later. Only a fragment of Mauretania Tingitana remained under Roman control. In 285, the emperor Diocletian reorganised what was left of the province to retain only the coastal strip between Lixus, Tingis and Septa (modern Ceuta). Although a Roman army was based in Tingis, it was decided that it would simply be too expensive to mount a reconquest of a vulnerable border region.[24]

Volubilis continued to be inhabited for centuries after the end of Roman control. Latin was spoken (and used on documents and inscriptions) at least until the end of the 7th century. By the time the Arabs had arrived in AD 708,[27] the city – its name now changed to Berber Oualila or Walīlī – was inhabited by Christians and some Jews, many of whose ancestors had fled the persecutions and heavy taxes of the late Roman Empire. Much of the city centre had been abandoned and turned into a cemetery, while the centre of habitation had moved to the southwest alongside the banks of the Khourmane river. A wall divided the Roman city centre from the new town.[24] It remained fully Romanised: Latin inscriptions from the early 7th century commemorate multiple members of the gens Julia, who appear to have been the ruling family of the time[28] and Latin inscriptions continued to be made as late as AD 65,[29] while Volubilis remained mostly Christian until the second half of the 8th century.

The inhabitants of Volubilis, who were by now probably for the most part members of the Berber Baquates tribe, during the fifth century moved to the west of the triumphal arch, where they built a new residential area near the wadi Khoumane. This was separated from the upper part of the old Roman city by a new defensive wall, which came down to the river bank.The area of the triumphal arch became the cemetery of this Christian community. Four inscriptions dated to between 599 and 655 AD reveal that this was a Christian community with Roman civic institutions still in place. – UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Volubilis #836 (World Heritage List)

Volubilis remained the capital of the region well into the Islamic period. Islamic coins dating to the mid-8th century have been found on the site, attesting to the arrival of Islam in this part of Morocco. [25] It was here that Moulay Idriss established the Idrisid dynasty of Morocco in AD 788, after being welcomed by the Christian rulers of Volubilis. A direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, he escaped to Morocco from Syria and was proclaimed "commander of the faithful" in Volubilis, which was then occupied by the Berber tribe of the Awraba, under Ishaq ibn Mohammad. He married Ishaq's daughter and fathered a son, Idris II, who was proclaimed imam in Volubilis. Idriss II subsequently founded the city of Fes to serve as his new capital, depriving Volubilis of its last vestiges of political significance.[30] According to historian Noé Villaverde it was under Moulay Idriss and Idriss II that the last few inhabitants of Volubilis started definitively losing their last Romanized characteristics of the neolatin language and the Christian faith.

A Muslim group known as the "Rabedis", who had revolted in Córdoba in Al-Andalus (Andalusia in modern Spain), resettled at Volubilis in AD 818.[25] Although partially romanised berbers people continued to live in Volubilis for several more centuries, it was probably totally deserted by the 11th century even if there are evidences of Christianity being worshipped in the area.[30] Indeed in the area of Volubilis was created a catholic Dioceses in AD 1226.[31]

The name of the city was forgotten and it was termed Ksar Faraoun, or the "Pharaoh's Castle", by the local people, alluding to a legend that the ancient Egyptians had built it.[32] Nonetheless some of its buildings remained standing, albeit ruined, until as late as the 17th century when Moulay Ismail ransacked the site to provide building material for his new imperial capital at Meknes. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake caused further severe destruction.

See also

- Masuna

- Garmul

- Kusaila

- Romano-Berber states

- Roman 'Coloniae' in Berber Africa

- Rusadir

- Volubilis

- African Romance

- Christian Berbers

Notes

- ↑ Map of Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum in AD 590 on p. 361

- ↑ Noé Villaverde, Vega: "El Reino mauretoromano de Altava, siglo VI" (The Mauro-Roman kingdom of Altava) p.355

- ↑ Gilbert Meynier, the origins of Algeria, from prehistory to the advent of Islam, the Discovery 2011, p. 179-180

- ↑ Christian Djeddars

- ↑ Gabriel Camps. "Rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum. Recherches sur les royaumes de Maurétanie des VIe et VIIe siècles"

- ↑ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 16; Southern, 150; Williams, 75.

- ↑ Barnes, New Empire, 59; Williams, 75.

- ↑ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 16.

- ↑ Williams, 75.

- ↑ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 16; Barnes, New Empire, 59.

- ↑ Odahl, 58; Williams, 75.

- ↑ Wickham, Chris (2005). Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400 - 800. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-921296-5.

- ↑ Wickham, Chris (2005). Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400 - 800. Oxford University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-19-921296-5.

- ↑ In full, the inscription reads: "Pro sal(ute) et incol(umitate) reg(is) Masunae gent(ium) Maur(orum) et Romanor(um) castrum edific(atum) a Masgivini pref(ecto) de Safar. Iidir proc(uratore) castra Severian(a) quem Masuna Altava posuit, et Maxim(us) pr(ocurator) Alt(ava) prefec(it). P(ositum) p(rovinciae) CCCLXVIIII". The three officials are Masgiven in Safar, Iidir in Castra Severiana (exact location uncertain) and Maximus in Altava. 469 is provincial founding date, meaning 508. From Graham (1902: p.281). See also Martindale (1980: pp. 536, 734) and Merrills (2004: p.299).

- ↑ Aguado Blazquez, Francisco (2005). El Africa Bizantina: Reconquista y ocaso (PDF). p. 46.

- ↑ PLRE IIIa, p. 504

- ↑ El Africa Bizantina, pp. 45-46

- ↑ Masuna and Mastigas

- ↑ Encyclopedie Berbere: Les Djedars et les royaumes berbéro-romains des ve et vie siècles

- ↑ Les royaumes berberes

- ↑ McKenna, Amy (2011). The History of Northern Africa. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 1615303189.

- ↑ Conant, Jonathan (2012). Staying Roman : conquest and identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439-700. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 0521196973.

- ↑ Noé Villaverde Vega:"Tingitana en la antigüedad tardía, siglos III-VII: autoctonía y romanidad en el extremo occidente mediterráneo. (Seccion: Voluvilis en Mauritania)" p. 357-358

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 Rogerson 2010, p. 237.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Volubilis Project – History.

- ↑ MacKendrick 2000, p. 312.

- ↑ Davies 2009, p. 41.

- ↑ Conant 2012, p. 294.

- ↑ Halsall 2007, p. 410.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Rogerson 2010, p. 238.

- ↑ Creation of Dioceses of Fez

- ↑ Windus 1725, p. 86.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Timothy. The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-7837-2221-4

- Camps, Gabriel. Rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum. Recherches sur les royaumes de Maurétanie des VIe et VIIe siècles. Antiquités africaines. (Volume 20;Issue 20 pp. 183–218) Paris, 1984

- Conant, Jonathan. Staying Roman : conquest and identity in Africa and the Mediterranean (pag.439-700). Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 0521196973. Cambridge, 2012

- Davies, Ethel (2009). North Africa: The Roman Coast. Chalfont St Peter, Bucks: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-287-3.

- Halsall, Guy. Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 2007 ISBN 978-0-521-43491-1.

- LaPorte, Jean Pierre. Les Djedars, monuments funéraires Berbères de la région de Tiaret et Frenda. In "Identités et Cultures dans l'Algérie Antique", University of Rouen. Rouen, 2005 ISBN 2-87775-391-).

- MacKendrick, Paul Lachlan (2000). The North African Stones Speak. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-4942-2.

- Noé Villaverde, Vega Tingitana en la antigüedad tardía, siglos III-VII: autoctonía y romanidad en el extremo occidente mediterráneo. Ed. Real Academia de la Historia. Madrid, 2001 ISBN 8489512949, 9788489512948

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2010). Marrakesh, Fez and Rabat. Cadogan Guides. London, 2010 ISBN 978-1-86011-432-8.

- Williams, Stephen. Diocletian and the Roman Recovery. New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0-415-91827-8

- Windus, John. A journey to Mequinez, the residence of the present emperor of Fez and Morocco. Ed. Jacob Tonson. London, 1725 OCLC 64409967.

%2C_Algeria_04966r.jpg)