Readymades of Marcel Duchamp

The readymades of Marcel Duchamp are ordinary manufactured objects that the artist selected and modified, as an antidote to what he called "retinal art".[1] By simply choosing the object (or objects) and repositioning or joining, titling and signing it, the object became art.

Duchamp was not interested in what he called retinal art — art that was only visual — and sought other methods of expression. As an antidote to "retinal art" he began creating readymades at a time (1914) when the term was commonly used in the United States to describe manufactured items to distinguish them from handmade goods.

He selected the pieces on the basis of "visual indifference,"[2] and the selections reflect his sense of irony, humor and ambiguity. "...it was always the idea that came first, not the visual example," he said; "...a form of denying the possibility of defining art."

The first definition of "readymade" appeared in André Breton and Paul Éluard's Dictionnaire abrégé du Surréalisme: "an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist." While published under the name of Marcel Duchamp (or his initials, "MD," to be precise), André Gervais nevertheless asserts that Breton wrote this particular dictionary entry.[3]

Duchamp limited his yearly output of readymades, making no more than 20 in his lifetime. He felt that he could only avoid the trap of his own taste by limiting output, though he was aware of the contradiction of avoiding taste, yet also selecting an object. Taste, he felt, whether "good" or "bad," was the "enemy of art."

His conception of the readymade changed and developed over time. "My intention was to get away from myself, though I knew perfectly well that I was using myself. Call it a little game between 'I' and 'me,'" he said.[4]

Duchamp was unable to define or explain his opinion of readymades: "The curious thing about the readymade is that I've never been able to arrive at a definition or explanation that fully satisfies me."[5] Much later in life Duchamp said, "I'm not at all sure that the concept of the readymade isn't the most important single idea to come out of my work."[1]

The objects themselves

By submitting some of them as art to art juries, the public, and his patrons, Duchamp challenged conventional notions of what is, and what is not, art. Some were rejected by art juries and others went unnoticed at art shows.

Most of his early readymades have been lost or discarded, but years later he commissioned reproductions of many of them.

Types of readymades

- Readymades - un-altered objects

- Assisted readymades

- Rectified readymades

- Corrected readymades

- Reciprocal readymades - using Rembrandt as an ironing board.

Readymades

(Note: Some art historians consider only the un-altered manufactured objects to be readymades. This list includes the pieces he altered or constructed.)

Bottle Rack (also called Bottle Dryer or Hedgehog) (Egouttoir or Porte-bouteilles or Hérisson), 1914. Philadelphia Museum of Art

- A galvanized iron bottle drying rack that Duchamp bought in 1914 as an "already made" sculpture, but it gathered dust in the corner of his Paris studio because the idea of "readymade" had not yet been born. Two years later, through correspondence from New York with his sister, Suzanne Duchamp, in France he intended to make it a readymade by asking her to paint on it "(from) Marcel Duchamp." However, Suzanne, who was looking after his Paris studio, had already disposed of it.

Prelude to a Broken Arm (En prévision du bras cassé), 1915. External link

- Snow shovel on which he carefully painted its title. The first piece the artist called a "readymade." New to America, Duchamp had never seen a snow shovel not manufactured in France. With fellow Frenchman Jean Crotti he purchased it from a stack of them, took it to their shared studio, painted the title and "from Marcel Duchamp 1915" on it, and hung it from a wire in the studio. Many years later, a replica of the piece is said to have been mistaken for an ordinary snow shovel and used to move snow off the sidewalks of Chicago.

Pulled at 4 pins, 1915. External link

- An unpainted chimney ventilator that turns in the wind. The title is a literal translation of the French phrase, "tiré à quatre épingles," roughly equivalent to the English phrase "dressed to the nines." Duchamp liked that the literal translation meant nothing in English and had no relation to the object.

Comb (Peigne), 1916. Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Steel dog grooming comb inscribed along the edge in white, "3 ou 4 gouttes de hauteur n'ont rien a faire avec la sauvagerie; M.D. Feb. 17 1916 11 a.m." ("Three or Four Drops of Height [or Haughtiness] Have Nothing to Do with Savagery.")

Traveller's Folding Item (...pliant,... de voyage), 1916. External link

- Underwood Typewriter cover.

Fountain, 1917.

- Porcelain urinal inscribed "R. Mutt 1917." The board of the 1917 the Society of Independent Artists exhibit, of which Duchamp was a director, after much debate about whether Fountain was or was not art, hid the piece from view during the show.[6] Duchamp quickly quit the society, and the publication of Blind Man, which followed the exhibition was devoted to the controversy. Duchamp indicates in a 1917 letter to his sister that a female friend was centrally involved in the conception of this work. As he writes: "One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture."[7] The piece is more in line with the scatological aesthetics of Duchamp's friend, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, than Duchamp's, and the case has been made that she may well have had a hand in the conception of Fountain.[8]

Trap (Trébuchet), 1917. External link

- Wood and metal coatrack. Duchamp submitted it to a show at the Bourgeois Art Gallery and asked that it be placed near the entryway. It went unnoticed as art during the show.

50 cc of Paris Air (50 cc air de Paris, Paris Air or Air de Paris) (1919) Philadelphia Museum of Art (1919) Philadelphia Museum of Art (1949)

- A glass ampoule containing air from Paris. Duchamp took the ampoule to New York in 1920 and gave it to Walter Arensberg as a gift. The original was broken and replaced in 1949 by Duchamp. (Contrary to its title, the volume of air inside the ampoule was not actually 50 cubic centimeters, although when replicas were made in later decades, 50 cc of air was used. The original ampoule is thought to have contained around 125 cc of air.)

Fresh Widow, 1920.

The Brawl at Austerlitz, 1921. External link

Assisted readymades

Bicycle Wheel (Roue de bicyclette), 1913.Museum of Modern Art

- Bicycle wheel mounted by its fork on a painted wooden stool. He fashioned it to amuse himself by spinning it, "...like watching a fire... It was a pleasant gadget, pleasant for the movement it gave." The first readymade, though he initiated the ideas two years later. The original from 1913 was lost, and Duchamp recreated the sculpture in 1951.

- Bicycle Wheel is also said to be the first kinetic sculpture.[9]

With Hidden Noise (A bruit secret), 1916. Philadelphia Museum of Art

- A ball of twine between two brass plates, joined by four screws. An unknown object has been placed in the ball of twine by one of Duchamp's friends.

Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette

Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette

Unhappy readymade, 1919. External link

- Duchamp instructed his sister Suzanne to hang a geometry textbook from the balcony of her Paris apartment so that the problems and theorems, exposed to the test of the wind, sun and rain, could "get the facts of life." Suzanne carried out the instructions and painted a picture of the result.

Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette, 1921. External link

- A perfume bottle in the original box. An intriguing punning object, it was auctioned in 2009 for $11.5 million.

Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy?, 1921.

- Marble cubes in the shape of sugar lumps with a thermometer and cuttle bones in a small bird cage.

Rectified readymades

Pharmacy (Pharmacie), 1914External link

- Gouache on chromolithograph of a scene with bare trees and a winding stream to which he added two dots of watercolor, red and green, like the colored liquids in a pharmacy.

Apolinère Enameled, 1916-1917. Philadelphia Museum of Art

- A Sapolin paint advertisement.

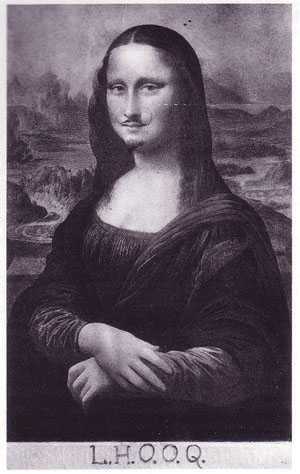

L.H.O.O.Q., 1919.

- Pencil on a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa on which he drew a goatee and moustache. The name, when pronounced in French, is a coarse pun — "elle a chaud au cul", translating colloquially as "she's got a hot ass" or "her ass is on fire".[10]

Wanted, $2,000 Reward, 1923. External link

- Photographic collage on poster.

Doubts over readymades

Research published in 1997 by Rhonda Roland Shearer questions whether Duchamp's "found objects" objects may actually have been created by Duchamp. Her research of items like snow shovels and bottle racks in use at the time failed to turn up any identical matches to photographs of the originals. However, there are accounts of Walter Arensberg and Joseph Stella being with Duchamp when he purchased the original Fountain at J. L. Mott Iron Works. Such investigations are hampered by the fact that few of the original "readymades" survive, having been lost or destroyed. Those that still exist are predominantly reproductions authorized or designed by Duchamp in the final two decades of his life. Shearer also asserts that the artwork L.H.O.O.Q. which is recorded to be a poster-copy of the Mona Lisa with a moustache drawn on it, is not the true Mona Lisa, but Duchamp's own slightly-different version that he modelled partly after himself. The inference of Shearer's viewpoint is that Duchamp was creating an even larger joke than he admitted.[11]

Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. Original painting from circa 1503–1507. Oil on poplar. |

See also

- Anti-art

- Maurizio Cattelan Another Fucking Readymade (1996)

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography, page 158.

- ↑ Cabanne: Dialogs with Marcel Duchamp, Thames and Hudson (1971), page 48. Cabanne: What determined your choice of readymades? Duchamp: That depended on the object. In general, I had to beware, at the end of fifteen days, you begin to like it or hate it. You have to approach something with indifference, as if you had no aesthetic emotion. The choice of readymades is always based on visual indifference and, at the same time, on the total absence of good or bad taste.

- ↑ Obalk, Hector: "The Unfindable Readymade", toutfait.com, Issue 2, 2000.

- ↑ Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography, page 160.

- ↑ Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography, page 159.

- ↑ Cabanne: Dialogs with Marcel Duchamp, page 55.

- ↑ Duchamp, Marcel trans. and qtd. in Gammel, Baroness Elsa, 224.

- ↑ Gammel, Baroness Elsa, 224-225.

- ↑ Atkins, Robert: Artspeak, 1990, Abbeville Press, ISBN 1-55859-010-2

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp.net, retrieved December 9, 2009

- ↑ Shearer, Rhonda Roland: "Marcel Duchamp's Impossible Bed and Other 'Not' Readymade Objects: A Possible Route of Influence From Art To Science", 1997.

- References

- Cabanne, Pierre: Dialogs with Marcel Duchamp, Da Capo Press, Inc., 1979 (1969 in French), ISBN 0-306-80303-8

- Gammel, Irene. Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002, 224.

- Girst, Thomas: "(Ab)Using Marcel Duchamp: The Concept of the Readymade in Post-War and Contemporary American Art", toutfait.com, Issue 5, 2003

- Hulten, Pontus (editor): Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life, The MIT Press, 1993. ISBN 0-262-08225-X

- Tomkins, Calvin: Duchamp: A Biography. Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0-8050-5789-7

- Toutfait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal

External links

- smARThistory: Duchamp's Readymades

- Unmaking the Museum: Marcel Duchamp's Readymades in Context

- Marcel Duchamp's Readymades (DADA Companion)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||