Rational consequence relation

In logic, a rational consequence relation is a non-monotonic consequence relation satisfying certain properties listed below.

Properties

A rational consequence relation satisfies:

- REF

- Reflexivity

and the so-called Gabbay-Makinson rules:

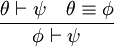

- LLE

- Left Logical Equivalence

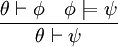

- RWE

- Right-hand weakening

- CMO

- Cautious monotonicity

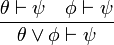

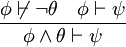

- DIS

- Logical or (ie disjunction) on left hand side

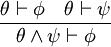

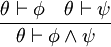

- AND

- Logical and on right hand side

- RMO

- Rational monotonicity

Uses

The rational consequence relation is non-monotonic, and the relation  is intended to carry the meaning theta usually implies phi or phi usually follows from theta. In this sense it is more useful for modeling some everyday situations than a monotone consequence relation because the latter relation models facts in a more strict boolean fashion - something either follows under all circumstances or it does not.

is intended to carry the meaning theta usually implies phi or phi usually follows from theta. In this sense it is more useful for modeling some everyday situations than a monotone consequence relation because the latter relation models facts in a more strict boolean fashion - something either follows under all circumstances or it does not.

Example

The statement "If a cake contains sugar then it tastes good" implies under a monotone consequence relation the statement "If a cake contains sugar and soap then it tastes good." Clearly this doesn't match our own understanding of cakes. By asserting "If a cake contains sugar then it usually tastes good" a rational consequence relation allows for a more realistic model of the real world, and certainly it does not automatically follow that "If a cake contains sugar and soap then it usually tastes good."

Note that if we also have the information "If a cake contains sugar then it usually contains butter" then we may legally conclude (under CMO) that "If a cake contains sugar and butter then it usually tastes good.". Equally in the absence of a statement such as "If a cake contains sugar then usually it contains no soap" then we may legally conclude from RMO that "If the cake contains sugar and soap then it usually tastes good."

If this latter conclusion seems ridiculous to you then it is likely that you are subconsciously asserting your own preconceived knowledge about cakes when evaluating the validity of the statement. That is, from your experience you know that cakes which contain soap are likely to taste bad so you add to the system your own knowledge such as "Cakes which contain sugar do not usually contain soap.", even though this knowledge is absent from it. If the conclusion seems silly to you then you might consider replacing the word soap with the word eggs to see if it changes your feelings.

Example

Consider the sentences:

- Young people are usually happy

- Drug abusers are usually not happy

- Drug abusers are usually young

We may consider it reasonable to conclude:

- Young drug abusers are usually not happy

This would not be a valid conclusion under a monotonic deduction system (omitting of course the word 'usually'), since the third sentence would contradict the first two. In contrast the conclusion follows immediately using the Gabbay-Makinson rules: applying the rule CMO to the last two sentences yields the result.

Consequences

The following consequences follow from the above rules:

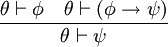

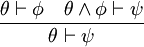

- MP

- Modus ponens

- MP is proved via the rules AND and RWE.

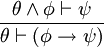

- CON

- Conditionalisation

- CC

- Cautious Cut

- The notion of Cautious Cut simply encapsulates the operation of conditionalisation, followed by MP. It may seem redundant in this sense, but it is often used in proofs so it is useful to have a name for it to act as a shortcut.

- SCL

- Supraclassity

- SCL is proved trivially via REF and RWE.

Rational consequence relations via atom preferences

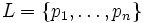

Let  be a finite language. An atom is a formula of the form

be a finite language. An atom is a formula of the form  (where

(where  and

and  ). Notice that there is a unique valuation which makes any given atom true (and conversely each valuation satisfies precisely one atom). Thus an atom can be used to represent a preference about what we believe ought to be true.

). Notice that there is a unique valuation which makes any given atom true (and conversely each valuation satisfies precisely one atom). Thus an atom can be used to represent a preference about what we believe ought to be true.

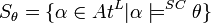

Let  be the set of all atoms in L. For

be the set of all atoms in L. For  SL, define

SL, define  .

.

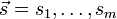

Let  be a sequence of subsets of

be a sequence of subsets of  . For

. For  ,

,  in SL, let the relation

in SL, let the relation  be such that

be such that  if one of the following holds:

if one of the following holds:

for each

for each

for some

for some  and for the least such i,

and for the least such i,  .

.

Then the relation  is a rational consequence relation. This may easily be verified by checking directly that it satisfies the GM-conditions.

is a rational consequence relation. This may easily be verified by checking directly that it satisfies the GM-conditions.

The idea behind the sequence of atom sets is that the earlier sets account for the most likely situations such as "young people are usually law abiding" whereas the later sets account for the less likely situations such as "young joyriders are usually not law abiding".

Notes

- By the definition of the relation

, the relation is unchanged if we replace

, the relation is unchanged if we replace  with

with  ,

,  with

with  ... and

... and  with

with  . In this way we make each

. In this way we make each  disjoint. Conversely it makes no difference to the rcr

disjoint. Conversely it makes no difference to the rcr  if we add to subsequent

if we add to subsequent  atoms from any of the preceding

atoms from any of the preceding  .

.

The representation theorem

It can be proven that any rational consequence relation on a finite language is representable via a sequence of atom preferences above. That is, for any such rational consequence relation  there is a sequence

there is a sequence  of subsets of

of subsets of  such that the associated rcr

such that the associated rcr  is the same relation:

is the same relation:

Notes

- By the above property of

, the representation of an rcr

, the representation of an rcr  need not be unique - if the

need not be unique - if the  are not disjoint then they can be made so without changing the rcr and conversely if they are disjoint then each subsequent set can contain any of the atoms of the previous sets without changing the rcr.

are not disjoint then they can be made so without changing the rcr and conversely if they are disjoint then each subsequent set can contain any of the atoms of the previous sets without changing the rcr.