Rate-monotonic scheduling

In computer science, rate-monotonic scheduling (RMS)[1] is a scheduling algorithm used in real-time operating systems (RTOS) with a static-priority scheduling class.[2] The static priorities are assigned on the basis of the cycle duration of the job: the shorter the cycle duration is, the higher is the job's priority.

These operating systems are generally preemptive and have deterministic guarantees with regard to response times. Rate monotonic analysis is used in conjunction with those systems to provide scheduling guarantees for a particular application.

Introduction

A simple version of rate-monotonic analysis assumes that threads have the following properties:

- No resource sharing (processes do not share resources, e.g. a hardware resource, a queue, or any kind of semaphore blocking or non-blocking (busy-waits))

- Deterministic deadlines are exactly equal to periods

- Static priorities (the task with the highest static priority that is runnable, immediately preempts all other tasks)

- Static priorities assigned according to the rate monotonic conventions (tasks with shorter periods/deadlines are given higher priorities)

- Context switch times and other thread operations are free and have no impact on the model

It is a mathematical model that contains a calculated simulation of periods in a closed system, where round-robin and time-sharing schedulers fail to meet the scheduling needs otherwise. Rate monotonic scheduling looks at a run modeling of all threads in the system and determines how much time is needed to meet the guarantees for the set of threads in question.

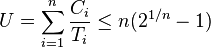

Liu & Layland (1973) proved that for a set of n periodic tasks with unique periods, a feasible schedule that will always meet deadlines exists if the CPU utilization is below a specific bound (depending on the number of tasks). The schedulability test for RMS is:

where Ci is the computation time, Ti is the release period (with deadline one period later), and n is the number of processes to be scheduled. For example, U ≤ 0.8284 for two processes. When the number of processes tends towards infinity, this expression will tend towards:

Therefore, a rough estimate is that RMS can meet all of the deadlines if CPU utilization is less than 69.32%. The other 30.7% of the CPU can be dedicated to lower-priority non real-time tasks. It is known that a randomly generated periodic task system will meet all deadlines when the utilization is 85% or less,[3] however this fact depends on knowing the exact task statistics (periods, deadlines) which cannot be guaranteed for all task sets.

The rate-monotonic priority assignment is optimal, meaning that if any static-priority scheduling algorithm can meet all the deadlines, then the rate-monotonic algorithm can too. The deadline-monotonic scheduling algorithm is also optimal with equal periods and deadlines, in fact in this case the algorithms are identical; in addition, deadline monotonic scheduling is optimal when deadlines are less than periods.[4] For the task model in which deadlines can be greater than periods, Audsley's algorithm endowed with an exact schedulability test for this model finds an optimal priority assignment.[5]

Avoiding priority inversion

In many practical applications, resources are shared and the unmodified RMS will be subject to priority inversion and deadlock hazards. In practice, this is solved by disabling preemption or by priority inheritance. Alternative methods are to use lock free algorithms or avoid the sharing of a mutex/semaphore across threads with different priorities. This is so that resource conflicts cannot result in the first place.

Disabling of preemption

- The

OS_ENTER_CRITICAL()andOS_EXIT_CRITICAL()primitives that lock CPU interrupts in a real-time kernel, e.g. MicroC/OS-II - The

splx()family of primitives which nest the locking of device interrupts (FreeBSD 5.x/6.x),

Priority inheritance

- The basic priority inheritance protocol[6] promotes the priority of the task that holds the resource to the priority of the task that requests that resource at the time the request is made. Upon release of the resource, the original priority level before the promotion is restored. This method does not prevent deadlocks and suffers from chained blocking. That is, if a high priority task accesses multiple shared resources in sequence, it may have to wait (block) on a lower priority task for each of the resources.[7] The real-time patch to the Linux kernel includes an implementation of this protocol.[8]

- The highest locker protocol raises the priority of the task during its use of a resource to the highest among the priorities of all tasks that ever use that resource. The priority ceiling for each resource can be precomputed at system design time. This protocol prevents deadlocks and bounds the blocking time to at most the length of one lower priority critical section.[9]

- The priority ceiling protocol[10] enhances the basic priority inheritance protocol by assigning a ceiling priority to each semaphore, which is the priority of the highest job that will ever access that semaphore. A job cannot preempt a lower priority critical section if its priority is lower than the ceiling priority for that section. This method prevents deadlocks and bounds the blocking time to at most the length of one lower priority critical section. This method can be suboptimal, in that it can cause unnecessary blocking. The priority ceiling protocol is available in the VxWorks real-time kernel.

Priority inheritance algorithms can be characterized by two parameters. First, is the inheritance lazy (only when essential) or immediate (boost priority before there is a conflict). Second is the inheritance optimistic (boost a minimum amount) or pessimistic (boost by more than the minimum amount):

| pessimistic | optimistic | |

|---|---|---|

| immediate | OS_ENTER_CRITICAL() / OS_EXIT_CRITICAL() |

splx(), highest locker |

| lazy | priority ceiling protocol, basic priority inheritance protocol | |

In practice there is no mathematical difference (in terms of the Liu-Layland system utilization bound) between the lazy and immediate algorithms, and the immediate algorithms are more efficient to implement, and so they are the ones used by most practical systems.

An example of usage of basic priority inheritance is related to the "Mars Pathfinder reset bug" [11][12] which was fixed on Mars by changing the creation flags for the semaphore so as to enable the priority inheritance.

Example

| Process | Execution Time | Period |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1 | 8 |

| P2 | 2 | 5 |

| P3 | 2 | 10 |

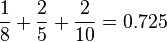

The utilization will be:

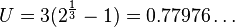

The sufficient condition for  processes, under which we can conclude that the system is schedulable is:

processes, under which we can conclude that the system is schedulable is:

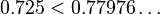

Since  the system is surely schedulable.

the system is surely schedulable.

But remember, this condition is not a necessary one. So we cannot say that a system with higher utilization is not schedulable with this scheduling algorithm.

See also

- Deos, a time and space partitioned real-time operating system containing a working Rate Monotonic Scheduler.

- Deadline-monotonic scheduling

- Dynamic priority scheduling

- Earliest deadline first scheduling

- RTEMS, an open source real-time operating system containing a working Rate Monotonic Scheduler.

- Scheduling (computing)

References

- ↑ Liu, C. L.; Layland, J. (1973), "Scheduling algorithms for multiprogramming in a hard real-time environment", Journal of the ACM 20 (1): 46–61, doi:10.1145/321738.321743.

- ↑ Bovet, Daniel P.; Cesati, Marco, Understanding the Linux Kernel, http://oreilly.com/catalog/linuxkernel/chapter/ch10.html#85347.

- ↑ Lehoczky, J.; Sha, L.; Ding, Y. (1989), "The rate monotonic scheduling algorithm: exact characterization and average case behavior", IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium, pp. 166–171, doi:10.1109/REAL.1989.63567.

- ↑ Leung, J. Y.; Whitehead, J. (1982), "On the complexity of fixed-priority scheduling of periodic, real-time tasks", Performance Evaluation 2 (4): 237–250, doi:10.1016/0166-5316(82)90024-4.

- ↑ Alan Burns and Andy Wellings (2009), Real-Time Systems and Programming Languages (4th ed.), Addison-Wesley, pp. 391,397, ISBN 978-0-321-41745-9

- ↑ Lampson, B. W.; Redell, D. D. (1980), "Experience with processes and monitors in Mesa", Communications of the ACM 23 (2): 105–117, doi:10.1145/358818.358824.

- ↑ Buttazzo, Giorgio (2011), Hard Real-Time Computing Systems: Predictable Scheduling Algorithms and Applications (Third ed.), New York, NY: Springer, p. 225

- ↑ "Real-Time Linux Wiki". kernel.org. 2008-03-26. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ↑ Buttazzo, Giorgio (2011), Hard Real-Time Computing Systems: Predictable Scheduling Algorithms and Applications (Third ed.), New York, NY: Springer, p. 212

- ↑ Sha, L.; Rajkumar, R.; Lehoczky, J. P. (1990), "Priority inheritance protocols: an approach to real-time synchronization", IEEE Transactions on Computers 39 (9): 1175–1185, doi:10.1109/12.57058.

- ↑ http://research.microsoft.com/~mbj/Mars_Pathfinder/

- ↑ http://anthology.spacemonkeys.ca/archives/770-Mars-Pathfinder-Reset-Bug.html

Further reading

- Buttazzo, Giorgio (2011), Hard Real-Time Computing Systems: Predictable Scheduling Algorithms and Applications, New York, NY: Springer.

- Alan Burns and Andy Wellings (2009), Real-Time Systems and Programming Languages (4th ed.), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-321-41745-9

- Liu, Jane W.S. (2000), Real-time systems, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Chapter 6.

- Joseph, M.; Pandya, P. (1986), "Finding response times in real-time systems", BCS Computer Journal 29 (5): 390–395, doi:10.1093/comjnl/29.5.390.

- Sha, Lui; Goodenough, John B. (April 1990), "Real-Time Scheduling Theory and Ada", IEEE Computer 23 (4): 53–62, doi:10.1109/2.55469

External links

- Mars Pathfinder Bug from Research @ Microsoft

- What really happened on Mars Rover Pathfinder by Mike Jones from The Risks Digest, Vol. 19, Issue 49

![\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} n(\sqrt[n]{2} - 1) = \ln 2 \approx 0.693147\ldots](../I/m/362dc1a4438ec99d7387afcad4b3ab69.png)