Randall Holden

| Randall Holden | |

|---|---|

| Born |

c. 1612 Wiltshire, England |

| Died |

23 Aug 1692 Warwick, Rhode Island |

| Education | Sufficient to hold many important civic positions and draft letters to the King |

| Occupation | Councilman, Assistant, Moderator, Commissioner, Deputy |

| Religion | follower of Samuel Gorton |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Dungan |

| Children | Frances, Elizabeth, Mary, John, Sarah, Randall, Margaret, Charles, Barbara, Susannah, Anthony |

Randall Holden (c. 1612 – 1692) was an early inhabitant of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, was one of the original founders of Portsmouth, and one of the co-founders of the town of Warwick. Coming from Salisbury in England, he is first recorded in New England as one of the signers of the compact establishing the settlement of Portsmouth by followers of the banished dissident minister, Anne Hutchinson. Following a few years on Aquidneck Island (called Rhode Island), he joined Samuel Gorton and ten others in establishing the town of Warwick in early 1643, on land purchased of the Indian sachems.

The first few years of the Warwick settlement were fraught with difficulty, and the settler's lands were claimed by Massachusetts, who sent soldiers to apprehend the Warwick settlers for supposed infractions against the local Indian sachems. The Warwick settlers were hauled off to face trial in Boston, but their charges had nothing to do with the sachems; instead they were charged with heresy and sedition based on their religious views. Being sent to various jails in the Boston area, they were eventually released, but were banished not only from the Massachusetts colony, but also from their own Warwick lands. Holden soon thereafter joined Gorton and John Greene on a trip to England to seek redress for the wrongs committed against them. Being successful in their mission, Holden and Greene returned to New England in 1646 with a new charter for their settlement, and protection from the crown.

Upon returning to the Rhode Island colony, Holden became heavily involved in the affairs of his town of Warwick, and of the entire colony. During the next 40 years he frequently served in a variety of roles as councilman and treasurer at the town level, and in the colony he was often Assistant to the President (or Governor), Commissioner, or Deputy. Holden was so highly respected within the colony that in 1676 during the dire events of King Philip's War he was one of 16 of the colony's most esteemed citizens to be called to the General Assembly for their counsel. Holden continued to serve the colony into his mid 70s, only a few years before his death in 1692 at the age of 80.

Life

Randall Holden was born about 1612, and originated in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England.[1] He sailed to New England as a young man, and the first record of his name occurred when he and Roger Williams witnessed the deed whereby the Indian sachems Canonicus and Miantonomo sold Aquidneck Island to William Coddington for the settlement of Portsmouth by the followers of Anne Hutchinson.[1] He had apparently lived in Boston, because this is where the signing of the Portsmouth Compact took place, and his signature is 19th on the list of the 23 names on that document. In this compact, the followers of Hutchinson established a non-sectarian civil government upon the universal consent of the inhabitants, with a Christian focus.[2] Planning initially to settle in New Netherland, the group was persuaded by Roger Williams to purchase some land of the Indians on the Narragansett Bay. This they did, settling on the north east end of Aquidneck Island, and establishing a settlement they called Pocasset, but in 1639 changing the name to Portsmouth.[3] William Coddington was elected the first chief magistrate of the settlement, not being called Governor, but instead using the Biblical title of Judge.[4]

Holden became part of this initial settlement of Portsmouth and in his first year there in 1638 he was made Marshall, was elected as Corporal, and was given a grant of five acres.[1] He soon became part of the new establishment of Newport, but in March 1641 he was disenfranchised from the government there with three others, and their names were cancelled from the Roll of Freeman of Newport.[1] Some time the following year he and others desired to reunite with the island government (Portsmouth and Newport), and were "readily embraced" by the colony.[1]

Holden became a follower of Samuel Gorton, and in January 1643 Gorton, Holden and ten others bought a large tract of land from the Narragansett tribal chief Miantonomo for 144 fathoms (864 feet or 263 meters) of wampum, and they called the place Shawomet, using the native name, which would later be changed to Warwick.[5] Later that year he and others of Shawomet were summoned to appear in court in Boston to answer a complaint from two Indian sachems concerning some "unjust and injurious dealing" towards them. The Shawomet men refused the summons, claiming that they were loyal subjects of the King of England and beyond the jurisdiction of Massachusetts.[6] Soldiers were soon sent after them, their writings were confiscated, and the men were taken to Boston for trial.[6][7] Once tried, the charges against Holden and the others had nothing to do with the original charges, but instead were about their writings and beliefs.[6] The men were charged with heresy and sedition, and sentenced to confinement, and threatened with death should they "break jail, or preach their heresies or speak against church or state."[6] The men were imprisoned in different towns in the Boston area, and Holden was sent to Salem.[6]

The sentencing took place in November 1643, but a few months later, in March 1644, Holden was released from prison, being banished from both Massachusetts and from Shawomet (which was claimed by Massachusetts).[6] Seeking redress for the wrongs committed against them, later that year Gorton, Holden and John Greene boarded a ship in New Amsterdam and sailed back to England, where Holden and Greene spent two years, and Gorton would spend four years.[5] In 1646 Gorton, while in England, published one of his many writings, entitled Simplicity's Defence Against Seven Headed Policy, detailing the wrongs that were put upon the Shawomet settlers.[8] The same year he was given what he had come for: the Commissioner of Plantations, responsible for overseeing the activities of the colonies, issued an order to Massachusetts to allow the residents of Shawomet and other lands included in the patent to "freely and quietly live and plant" without being disquieted by external pressures.[8] In September 1646 Holden and Greene returned to Boston with a pass from the Commissioners of Plantations allowing them safe passage through the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Two years later, in 1648, Gorton returned to New England, landing in Boston that May. His arrest was ordered, but he also had a letter of protection from Robert Rich, 5th Earl of Warwick, which saw him safely back to his family.[8] In honour of the Earl's intercession in this colonial difficulty, Gorton changed the name of Shawomet to Warwick.[8]

Upon his return from England, Holden immediately became involved in the affairs of the town and colony. In 1647 he was on the Town Council, was Town Treasurer, and was frequently made the Moderator of town meetings.[6] In the same year he was also selected as Warwick's Assistant to the President of the colony, a position he would hold seven more times during the next 30 years.[6] He was also elected as Commissioner for six one-year terms from 1652 to 1663, and as a Deputy for eight terms between 1666 and 1686.[6] Holden's name appears on a list of Warwick freeman in 1655, and at some point he earned the title of Captain.[6]

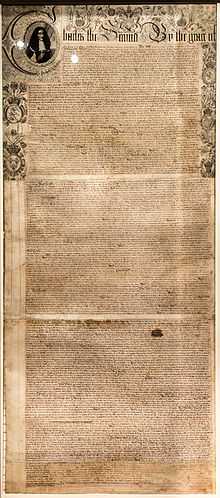

Holden was one of several prominent citizens named in the Royal Charter of 1663, which was delivered to the colony in November of that year, and which outlined a government with broad freedoms for the colony.[9] In 1671, he and others were authorised to make assessments on towns for back taxes.[6] Holden was very highly esteemed within the Rhode Island colony, so much so that in April 1676, during the chaos of King Philip's War, it was voted by the General Assembly that "in these troublesome times and straits in this colony, the Assembly, desiring to have the advice and concurrence of the most judicious inhabitants, if it may be had for the good of the whole, do desire at their sitting the company and counsel of...Randall Holden" and 15 others.[6] Among the others were former governors and deputy governors, including Benedict Arnold, Gregory Dexter, and James Barker.[10][11]

In 1679 Holden was once again in England, this time with John Greene, Jr., and wrote a letter to the Commissioners of Trade about Mount Hope, being a property disputed with the Plymouth Colony.[6] Two years later he sold 750 acres of land to Stephen Arnold (son of William Arnold), obtaining 119 pounds for the transaction, and in 1683 he was appointed to a committee to draft a letter to the King.[6] Holden continued to be active in civic affairs into his mid 70s, and in 1687 was appointed as Justice of the Court of Common Pleas.[6] He died on 23 August 1692, at a fairly advanced age.[6]

Family

Holden married Frances Dungan, the daughter of William and Frances (Latham) Dungan. With wife Frances, Holden had 11 children, one of whom was Randall Holden, Jr., who was very active in colonial affairs, serving for many years as Deputy, Assistant, Major, and Speaker of the House of Deputies.[1] Another son, Charles Holden, married Catharine Greene, a daughter of Deputy Governor John Greene, Jr., a granddaughter of fellow Warwick co-founder John Greene, and ancestors of state governor William Greene. Their daughter Susannah Holden married Benjamin Greene, another grandson of Warwick co-founder John Greene.[6] A great grandson through his daughter Frances was John Gardner who served as the deputy governor of the colony for several years, and was also the sixth Chief Justice of the colony's Superior Court.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Austin 1887, p. 100.

- ↑ Bicknell 1920, p. 992.

- ↑ Bicknell 1920, p. 993.

- ↑ Bicknell 1920, pp. 992–3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Austin 1887, p. 101, 302.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Austin 1887, p. 101.

- ↑ Gorton 1907, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Austin 1887, p. 304.

- ↑ Laws of Nature.

- ↑ Austin 1887, p. 14.

- ↑ Bicknell 1920, p. 1022.

Bibliography

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol.3. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 992–3.

- Gorton, Adelos (1907). The Life and Times of Samuel Gorton. George S. Ferguson Co.

Online sources

- "Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations". The Laws of Nature and Nature's God. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||