Raid on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia (1756)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Raid on Lunenburg occurred during the French and Indian War when a militia of the Wabanaki Confederacy (Mi'kmaw) attacked a British settlement at Lunenburg, Nova Scotia on May 8, 1756.[1][2] The native militia raided two islands on the northern outskirts of the fortified Township of Lunenburg, [John] Rous Island and Payzant Island (present day Covey Island).[3] The Maliseet killed twenty settlers and took five prisoners. This raid was the first of nine the Natives and Acadians would conduct against the peninsula over a three-year period during the war. The Wabanaki Confederacy took John and Lewis Payzant prisoner, both of whom recorded one of the few Captivity narratives that exist from Nova Scotia/ Acadia.

Historical context

The first recorded Mi'kmaq militia attack in the region happened during King Georges War on the La Have river. The militia killed seven English crew members on a vessel the went ashore. The scalps were taken to Joseph Marin de la Malgue at Louisbourg.[4]

Father Le Loutre's War began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.[5] By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726).[6] The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (Citadel Hill) (1749), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754).

To thwart the development of these Protestant settlements, the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq and Acadians conducted numerous raids on the settlements, such as the Raid on Dartmouth (1751). During these raids, the French military paid the Mi'kmaq for the British scalps they acquired. (In response, the British military paid Rangers for the scalps of Mi'kmaq and Maliseet.)[7]

When the French and Indian War began, the conflict in Acadia intensified. With the British victory at the Battle of Fort Beauséjour (1755), the Expulsion of the Acadians from the Maritimes began and conflict between the British and the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and Maliseet continued. Fort Cumberland was raided for two days between April 26–27, 1756, and nine British soldiers were killed and scalped.[8] The raid on Lunenburg took place almost two weeks later.

Raid on Lunenburg

The Governor General of New France, Pierre François de Rigaud, ordered the top military figure in Acadia Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot to send a Mi'kmaw militia to raid Lunenburg.[9] The French garrison was at Ste. Anne's Point (near present day Fredericton, New Brunswick), where Boishébert was stationed. This site was also close to the location of the Maliseet encampment Aukpaque.[10] The Maliseet left Aukpaque / Ste. Anne and arrived at the outskirts of Lunenburg on May 8, 1756. According to French reports, the Maliseet militia killed and scalped twenty settlers - men, women and children - and burned their homes, although British accounts suggest that only five were killed.[11] There was little resistance. The five remaining residents, Marie Anne Payzant and her four young children, were taken prisoner. Her husband Louis Payzant was one of the settlers who was killed and scalped.

Lieut-Colonel Patrick Sutherland, who was stationed at Lunenburg, immediately dispatched a company of 30 officers and soldiers to repel the raid. Upon their return on May 11, Deputy provost marshal Dettlieb Christopher Jessen reported the number killed was five and that the Maliseet militia and the prisoners were gone.[12]

Consequences

_McCord_Museum_McGill.jpg)

In response to the Lunenburg raid and the earlier raids on Fort Cumberland, on May 14, 1756, Governor Charles Lawrence created a bounty for the scalps of Mi'kmaq and Maliseet men.[13][14]

Upon learning that the victims were French (albeit Protestant French), on August 6, 1756, the Governor of New France considered the possibility of recruiting other French settlers at Lunenburg to burn the town and join the French occupied territories of Île St. Jean (Prince Edward Island) or Île Royale (Cape Breton Island).[15] While the burning of Lunenburg never took place, a number of the French and German-speaking Foreign Protestants left the village to join Acadian communities.[16]

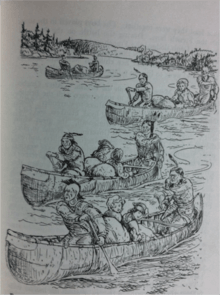

The Mi'kmaq took Marie Anne Payzant (who was in the first month of pregnancy) and her four young children over land and by canoe to Quebec City. Along the way they stopped at the French garrison at Ste. Anne's Point, where Boishébert, who had ordered the raid, was stationed. The Maliseet kept Marie Anne's children for ransom at their near-by village Aukpaque (present-day Springhill, New Brunswick and Eqpahak Island) and forced her to go to Quebec City without them. She gave birth while a prisoner of war on December 26, 1756.[17] The following summer, a ransom was paid and the rest of her children joined her in Quebec City. Marie Anne Payzant and her children spent four years in captivity (1756–1760). They were released after the Battle of Quebec and settled in present day Falmouth, Nova Scotia in 1761. Later in life, two of the surviving children recorded their captivity narratives after the Lunenburg raid.

In April 1757, a band of Acadian and Mi'kmaq partisans raided a warehouse near-by Fort Edward, killing thirteen British soldiers and, after taking what provisions they could carry, setting fire to the building. A few days later, the same partisans also raided Fort Cumberland.[18] Because of the strength of the Acadian militia and Mi'kmaq militia, British officer John Knox wrote that “In the year 1757 we were said to be Masters of the province of Nova Scotia, or Acadia, which, however, was only an imaginary possession.“ He continues to state that the situation in the province was so precarious for the British that the “troops and inhabitants” at Fort Edward, Fort Sackville and Lunenburg “could not be reputed in any other light than as prisoners."[19][20] (The militias had also contained British settlements at Dartmouth and Lawrencetown.)

The following year the militias engaged in the Lunenburg Campaign (1758).

See also

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Military history of the Maliseet people

- Military history of the Mi’kmaq people

References

- Primary sources

- Son John Payzant's account of the Raid of Lunenburg and his subsequent captivity can be found in Brian C. Cuthbertson, ed. "The Journal of the Reverend John Payzant (1749-1834)", Hantsport, N.S.: Lancelot Press, 1981.

- Son Lewis Payzant's account can be found in Silas Tertius Rand, "Early Provincial Settlers", The Provincial, Halifax, NS.: August 1852, Vol. 1, No. 8.

- An account by Dr. Elias Payzant, a grandchild of Marie Anne Payzant, can be found in the Payzant family papers, NSARM, MG1, Vol. 747, No. 42.

- Secondary sources

- John Payzant - Canadian Biography

- Bell, Winthrop Pickard. The "Foreign Protestants" and the Settlement of Nova Scotia:The History of a piece of arrested British Colonial Policy in the Eighteenth Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961

- Mather Byles DesBrisay (1895). History of the county of Lunenburg.

- Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing.

- Linda G. Wood (1993). "The Lunenburg Indian Raids of 1776 and 1778: A New documentary source." Nova Scotia Historical Review. Vol. 13. No. 1 pp. 93–108.

- Linda G. Wood (1996). "Murder among the Planters: A profile of Malachi Caigin of Falmouth, Nova Scotia." Nova Scotia Historical Review, Vol. 16. No. 1. pp. 96–108.

- Endnotes

- ↑ Diane Marshall in her book Heroes of the Acadian Resistance (Formac, 2011. p. 149) identifies that members of the Mi'kmaq militia were involved in the raid.

- ↑ Some commentators have indicated that since the primary documents indicate that the natives were from St. John River, that they were Maliseet. Mi'kmaq also lived on the St. John River.

- ↑ These islands are located off of the present-day village of Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia. Mahone Bay was not established as a town until the twentieth century. At the time of the raid, this area was simply part of the farm lots of those who had property in the town of Lunenburg. Such was the case with Louis Payzant who owned property in the town of Lunenburg and was killed on his farm lot property on Payzant Island (which is present-day Covey Island) during the raid.

- ↑ History of Lunenburg County,p 343

- ↑ Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- ↑ Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html

- ↑ While the French military hired Natives to gather British scalps, the British military hired Rangers to gather French and Native scalps. The regiments of both the French and British militaries were not skilled at frontier warfare, while the Natives and Rangers were. British officers Cornwallis and Amherst both expressed dismay over the tactics of the rangers and the Mi'kmaq (See Grenier, p.152, Faragher, p. 405).

- ↑ Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 55

- ↑ Winthrop Bell, Foreign Protestants. University of Toronto. 1961. p. 505; Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 54

- ↑ Linda G. Layton, p. 62. (2003); The village of Aukpaque, was on the right bank of the St. John river, at Spring Hill. There was also a native village and council house on Isle Sauvage, a well known island in the river, about six miles above Fredericton.

- ↑ Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 55

- ↑ Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 54

- ↑ Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 55.

- ↑ Lawrence scalp bounty. Nova Scotia historical society

- ↑ Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 56

- ↑ Charles Morris. 1762. British Library, Manuscripts, Kings 205: Report of the State of the American Colonies. pp: 329-330.

- ↑ Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing, p. 76

- ↑ John Faragher. Great and Noble Scheme. Norton. 2005. p. 398.

- ↑ Knox. Vol. 2, p. 443 Bell, p. 514

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/cihm_36456#page/n461/mode/2up/search/reputed