Rafael Gambra Ciudad

| Rafael Gambra Ciudad | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Rafael Gambra Ciudad 1920 Madrid, Spain |

| Died |

2004 Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | academic |

| Known for | author, soldier |

Political party | CT |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Rafael Gambra Ciudad (Madrid, 1920 - Madrid, 2004), was a Spanish philosopher, author and a Carlist soldier.

Family and Youth

_01.jpg)

Rafael's parental family for centuries has been linked to Valle del Roncal in the Navarrese Pyrenees, though his father, Eduardo Gambra y Sanz, settled in Madrid and became a recognized architect. His key works are the office of Sociedad Gran Peña along the Gran Via and refurbishment of Palacio del Marqués de Miraflores. Rafael's mother, Rafaela Ciudad Orioles, was an Andalusian from Seville. She came from a distinguished family of civil servants, her father having been President of Tribunal Supremo. Both Rafael's parents were profoundly Catholic; politically his father sympathised with Carlism.

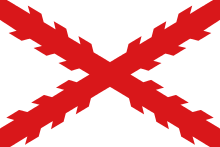

Gambra was born and raised in Madrid, though he spent much of his childhood in Navarre and later cherished his Navarrese heritage. As a result, his regional identity has always been torn between this of a madrileño and this of a navarro (though obituaries referred to him as arquetipo navarro). During his adolescent years Gambra was engaged in Asociación Católica Nacional de Propagandistas of Ángel Herrera, the lay Catholics organisation aiming at confronting the rising liberal and socialist tide; as a teenager he was reportedly averse towards the Christian-democratic tone of the group, favouring a fundamentalist approach of the ultra-conservative Carlists. He was still a schoolboy at the Marianist Colegio del Pilar when the Spanish Civil War broke out. As a 16-year-old Gambra enlisted to the Carlist Requeté militia and joined the Tercio de Abárzurza battalion, taking part in the unsuccessful offensive in Sierra de Guadarrama and fruitlessly attempting to break through the socialist defence lines to Madrid. José Ulíbarri, the Catholic parish priest from Úgar and temporary commander of the unit, remained Gambra's friend and sort of mentor for life.

He ended up in Tercio del Alcázar, a battalion composed mostly of the Castillians. Having spent most of the warfare in line, Gambra rose to the rank of wartime lieutenant (alférez provisional) and commanded a platoon when his unit reached the Valencian town of Lliria at the moment of Nationalist victory in 1939. Decorated with many military awards (Medalla de la Campaña 1936-1939, Cruz Roja del Mérito Militar, Cruz de Guerra, Medalla de Voluntarios de Navarra).

Rafael Gambra was married to Carmela Gutiérrez, one year his junior, also a Carlist activist, translator, journalist and (under the pen-name Miguel Arazuri) author of fairly popular novels in historical or contemporary settings (e.g. Marcos, La rata blanca, La bruja). She was particularly vigorous in public and private radio broadcasting, having been also the founder and manager of Fundación Stella, an independent radio venture. Apparently aware of the forthcoming mass culture era, she focused on proliferation rather than on creation and tried to influence her husband accordingly. The couple had three children. Some of their offspring became distinguished figures in the Spanish conservative realm; José Miguel Gambra Gutiérrez has been leading the sixtinos Carlists since 2010.

Scholarship and media

Straight from the war trenches Gambra went to university halls, studying letters and philosophy at the Universidad Central (later to become Universidad Complutense) in Madrid. He graduated in 1942, heavily influenced by Manuel García Morente, dean of the Facultad de Filosofía y Letra, and Salvador Minguijón Adrián, the Carlist theorist temporarily chairing cátedra de sociología in Madrid. The year later he entered Cuerpo de Catedráticos Numerarios de Institutos Nacionales de Enseñanza Media, commencing the 50-year-long career in education. Promoted to Inspector Nacional de Enseñanzas Medias, he was engaged in organisation and management of secondary education. In 1945 Gambra obtained his PhD laurels as Doctor en Filosofía, his thesis dedicated to post-Hegelian approach (from Marx to Feuerbach) to historiographical methodology; it was published in 1946. Later in the 1940s Gambra moved out from Madrid to Pamplona, where he was employed by Instituto Príncipe de Viana, a cultural outpost of Carlism managed by the provincial authorities, created few years earlier as a means of promoting Navarrese identity within the Francoist Spain. In the mid-1950s Gambra returned to the capital, taking posts in Instituto Cervantes and Instituto Lope de Vega, state-financed cultural and educational institutions. He co-operated also with Universidad Complutense, particularly with the associated San Pablo CEU college, run by Asociación Católica de Propagandistas. Gambra continued teaching at CEU from the mid-1960s to 1994, also after San Pablo formally separated from Complutense, becoming an independent private university.

In mid-1940s Gambra cultivated the Carlist identity when active in Academia Vazquez de Mella, a semi-official Carlist educational and cultural enterprise managed by a Catholic priest, Máximo Palomar. He kept contributing to various periodicals and journals. His pieces invariably promoted the Traditionalist outlook as much as the regime censhorship would have permitted. Initially he wrote to Arbor, Ateneo, El Alcázar and Biblioteca del Pensamiento Actual series, then to Siempre p'alante, La Nación, Montejurra and Tradición Católica, later switching to Carlist bulletins like La Santa Causa, the post-Francoist Fuerza Nueva and the unofficial organ of Spanish Integrist Christians Verbo. Throughout his career he remained most loyal to El Pensamiento Navarro, the sole Carlist daily spared amalgamation in the Francoist propaganda machine, occasionally publishing also in the foreign, mostly French legitimist papers. Awarded with a number of press prizes, like Premio Víctor Pradera (1973) or Premio Manuel Delgado Barreto (1996). Active in numerous Catholic groupings like Ciudad Católica, Priorato de la Hermandad de San Pío X or Movimiento Católico Español. Also engaged in private ventures flavoured by Carlism like Editorial Cálamo, a modestly successful publishing house run by his childhood friend, Ignacio Hernando de Larramendi.

Politics

Following the Nationalist victory in Civil War Gambra refrained from taking part in Francoist political structures, remaining loyal to the exiled Carlist regent-claimant Don Javier. In the early 1950s Gambra joined those Traditionalists who expected Don Javier to terminate the regency and announce his own claim to the throne. When this eventually happened in 1952, Gambra was (together with Francisco Elías de Tejada and Melchor Ferrer) the co-author of Acto de Barcelona, the proclamation issued by the pretender; this has already reflected Gambra's established position (despite his young age) as a recognised Traditionalist theorist.

Uneasy about the vacillation of Don Javier Gambra welcomed his son Carlos Hugo, who since 1957 represented the exiled claimant in Spain. Gambra appreciated his energetic style and focus on dynastic loyalty, though was worried by the perceived unfamiliarity of the francophone prince with the Spanish affairs. Later Gambra grew increasingly skeptical, suspecting the hugocarlistas of radically leftist ideas. In the late 1960s the power struggle within the movement was already rife; Gambra sided with José Maria Valiente against the Carlos Hugo supporters, whom he accused of incapacitating the aging Don Javier. In 1971, when Gambra summarised the Traditionalist vision of Carlism against the program promoted by the hugocarlistas in ¿Qué es el carlismo?, published jointly with de Tejada and Francisco Puy Muñoz, the balance of power has already clearly tilted towards the Progressives. When Carlos Hugo transformed Comunión into Partido Carlista, Gambra stayed out.

During the Spanish transition to democracy from 1975 onwards Gambra sided with the die-hard Francoist group of Fuerza Nueva until the party was dissolved in 1982. At that time Traditionalist Carlism was in total disarray, reduced to a number of grouplets created as slightly different but equally failed alternatives to Partido Carlista. Though most of them united in Comunión Tradicionalista Carlista in 1986, Gambra remained on the sidelines of politics. Instead he supported youth Carlist organisations, focusing on cultural heritage and education. His objective was to promote Traditionalist values in the increasingly secular, modern consumer Spanish society. He also aimed at challenging the competitive socialist vision of Partido Carlista, at that time abandoned by Carlos Hugo and, very much like Traditionalism, reduced to political folklore.

In the 1990s Gambra was considered supreme authority on theory of Traditionalism. This was acknowledged during the homage celebrations organised in 1998, though formal recognition came 3 years later. In 2001 Don Sixto, the younger son of Don Javier styled as Abanderado de la Tradición (though falling short either of claiming the throne or even claiming the Carlist regency) nominated Gambra chief of his Secretaría Política. Not all the Traditionalists recognized Gambra's authority; the carloctavistas and Comunión Tradicionalista Carlista (not admitting allegiance to any dynastical line) dissociated themselves from the nomination. Assuming political leadership of the sixtinos Carlists, the 81-year-old considered his elevation another cross to bear, though as an octogenarian Gambra remained fairly active; his last public appearance took place during the Cerro de los Ángeles feast in 2002.

Thought and Works

Though in mid-1940s Gambra was already a promising young conservative scholar of political thought, his outlook was fully formed during the days in Academia Vazquez de Mella, where he met and befriended Elías de Tejada, only 3 years his senior. The two studied pre-liberal monarchy and political theories of Carlism; their research was summarised almost simultaneously by de Tejada in La monarquía tradicional (1953) and by Gambra in La monarquía social y representativa en el pensamiento tradicional (1954). Both kept influencing each other and soon emerged as the most distinguished Carlist theorists of the late 20th century, though de Tejada pursued a disciplined scholarly approach in philosophy of law and politics, while Gambra formatted his key works as less rigid essays in culture and anthropology.

The principal thread of Gambra's thought is repudiation of the rationalism-based civilisation. Human life is understood not as means of self-fulfillment, but as commitment. The human habitat is perceived as a mansion in space and time; its primary expression is society, composed of three intertwinned elements: nature, animality and rationality, not to be reduced to any single of them. It comprises a religious foundation, with the transcendent factor an indispensable element of social equation. According to Gambra, religious dimension of the community should be firmly incorporated within its governing structures. Such a polity is best expressed as a "society of duties", united by common purpose and religious inspiration. A form of organisation which is not based on public orthodoxy can never be stable. Social self of a human is firmly expressed by tradition, viewed as accumulated and irreversible evolution that provides a principle governing historical societies. Tradition is defined as the cumulative progress and opposed to revolutionary patterns of change, deemed incompatible with development. This model is to be reflected in Spain by the principle of hereditary monarchy, executed by means of corporate representation and embodied into the federalist organisation.

The main body of Gambra's concept was introduced between the mid-1960s and mid-1980s, demonstrating his culturally fundamentalist, religiously integrist and politically anti-democratic outlook. La unidad religiosa y el derrotismo católico (1965) was centred on secularisation of Western polities and tackled the Christian-Democratic vision of liberal social organisation as ill-grounded. In El silencio de dios (1967) Gambra explored the roots of perceived cultural decline, striving to demonstrate how multifold advances of the last centuries have given man a false sense of mastery; the book was also a Catholic integrist critique of Vatican II. His Tradición o mimetismo (1976) tried to re-define the concepts of tradition and progress. Published in the midst of the Spanish transition it was dramatically out of tune with the prevailing mood, partially withdrawn by the editor and distributed by the author himself. Finally, El lenguaje y los mitos (1983) deconstructed the modern communication; its objective was to prove that the progressivist tide manipulated the language, subjected it to semantical transmutation and turned from means of communication into means of promoting cultural revolution.

Other

Most popular Gambra's works were textbooks in history of philosophy (Historia sencilla de la filosofía, 1961 and Curso elemental de filosofía, 1962); tailored for the beginners, they were reprinted in countless editions and served as immensely popular introductions to philosophy for generations of Spanish students. The first edition of Curso elemental was nominally co-authored by Gambra and Gustavo Bueno. In the subsequent 17 re-runs the publisher dropped Bueno altogether and credited the work exclusively to Gambra. After the fall of Francoism Bueno claimed that the result of his own labor had been merely re-edited by Gambra (to suit his Carlist leaning). Three of major Gambra's works fall into history: La primera guerra civil de España 1821-23 (1950), El Valle de Roncal (1974) and La Cristianización de América (1992). The massive yet still incomplete collection of Gambra's writings (released digitally in 2002) contains 775 titles, mostly hundreds of minor articles and essays published in various press titles.

See also

- Carlism

- Corporativism

- Integrism

- Francisco Elías de Tejada y Spínola

References

- Miguel Ayuso Torres, Koinós. El pensamiento político de Rafael Gambra, Madrid 1998, ISBN 8473440420, 9788473440424

- Miguel Ayuso Torres, El tradicionalismo de Gambra, [in:] Anales de la Fundación Francisco Elías de Tejada 2004 (10), ISSN 1137117X

- Miguel Ayuso Torres, Rafael Gambra (1920-2004) [in:] Razón española: Revista bimestral de pensamiento 2004 (124), ISSN 02125978

- Pedro Carlos Gonzáles Cuevas, El pensamiento político de la derecha española en el siglo XX, Madrid 2005, ISBN 8430942238

- Luis Hernando de Larramendi, Los Gambra y los Larramendi: una amistad carlista [in:] Anales de la Fundación Francisco Elías de Tejada 2004 (10), ISSN 1137117X

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis], Valencia 2009

- Carmelo López-Arias Montenegro, Rafael Gambra y el sentido del tiempo, [in:] Anales de la Fundación Francisco Elías de Tejada 2004 (10), ISSN 1137117X

- Manuel Santa Cruz, Rafael Gambra. un hombre cabal, [in:] Anales de la Fundación Francisco Elías de Tejada 2004 (10), ISSN 1137117X

External links

- Roncal Valley by Gambra

- Requetés in brief homage video

- Requetés in historical documentary video

- Gambra by Fundacion Nacional Francisco Franco

- Gambra by filosofia.org

- in memoriam Rafael Gambra by Anales de la Fundación Francisco Elías de Tejada

- Gambra by Ayuso

- Gambra by Nueva Hispanidad

- sixtinos Carlists, official site

- Catholic fundamentalism 1980s [East] on YouTube

- Catholic fundamentalism 1980s [West] on YouTube

- they come, in numbers and weapons far greater than our own - Narnia version of the ultimate battle on YouTube

- Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda (video) on YouTube