Radiation material science

Radiation materials science describes the interaction of radiation with matter: a broad subject covering many forms of irradiation and of matter.

Main aim of radiation material science

Some of the most profound effects of irradiation on materials occur in the core of nuclear power reactors where atoms comprising the structural components are displaced numerous times over the course of their engineering lifetimes. The consequences of radiation to core components includes changes in shape and volume by tens of percent, increases in hardness by factors of five or more, severe reduction in ductility and increased embrittlement, and susceptibility to environmentally induced cracking. For these structures to fulfill their purpose, a firm understanding of the effect of radiation on materials is required in order to account for irradiation effects in design, to mitigate its effect by changing operating conditions, or to serve as a guide for creating new, more radiation-tolerant materials that can better serve their purpose.

Radiation

The types of radiation that can alter structural materials consist of neutrons, ions, electrons and gamma rays. All of these forms of radiation have the capability to displace atoms from their lattice sites, which is the fundamental process that drives the changes in structural metals.The inclusion of ions among the irradiating particles provides a tie-in to other fields and disciplines such as the use of accelerators for the transmutation of nuclear waste, or in the creation of new materials by ion implantation, ion beam mixing, plasma assisted ion implantation and ion beam assisted deposition.

The effect of irradiation on materials is rooted in the initial event in which an energetic projectile strikes a target. While the event is made up of several steps or processes, the primary result is the displacement of an atom from its lattice site. Irradiation displaces an atom from its site, leaving a vacant site behind (a vacancy) and the displaced atom eventually comes to rest in a location that is between lattice sites, becoming an interstitial atom. The vacancy-interstitial pair is central to radiation effects in crystalline solids and is known as a Frenkel pair (FP). The presence of the Frenkel pair and other consequences of irradiation damage determine the physical effects, and with the application of stress, the mechanical effects of irradiation by the occurring of interstitial, phenomena, such as swelling, growth, phase transition, segregation, etc., will be effected. In addition to the atomic displacement, an energetic charged particle moving in a lattice also gives energy to electrons in the system, via the electronic stopping power. This energy transfer can also for high-energy particles produce damage in non-metallic materials, as so called ion tracks.[1][2]

Radiation damage

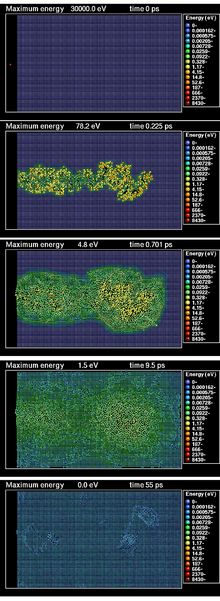

The radiation damage event is defined as the transfer of energy from an incident projectile to the solid and the resulting distribution of target atoms after completion of the event. This event is composed of several distinct processes:

- The interaction of an energetic incident particle with a lattice atom

- The transfer of kinetic energy to the lattice atom giving birth to a primary knock-on atom (PKA)

- The displacement of the atom from its lattice site

- The passage of the displaced atom through the lattice and the accompanying creation of additional knock-on atoms

- The production of a displacement cascade (collection of point defects created by the PKA)

- The termination of the PKA as an interstitial

The result of a radiation damage event is, if the energy given to a lattice atom is above the threshold displacement energy, the creation of a collection of point defects (vacancies and interstitials) and clusters of these defects in the crystal lattice.

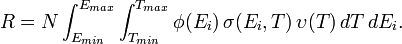

The essence of the quantification of radiation damage in solids is the number of displacements per unit volume per unit time  :

:

where  is the atom number density,

is the atom number density,  and

and  are the maximum and minimum energies of the incoming particle,

are the maximum and minimum energies of the incoming particle,  is the energy dependent particle flux,

is the energy dependent particle flux,  and

and  are the maximum and minimum energies transferred in a collision of a particle of energy

are the maximum and minimum energies transferred in a collision of a particle of energy  and a lattice atom,

and a lattice atom,  is the cross section for the collision of a particle of energy

is the cross section for the collision of a particle of energy  that results in a transfer of energy

that results in a transfer of energy  to the struck atom,

to the struck atom,  is the number of displacements per primary knock-on atom.

is the number of displacements per primary knock-on atom.

The two key variables in this equation are  and

and  . The term

. The term  describes the transfer of energy from the incoming particle to the first atom it encounters in the target, the primary knock-on atom (PKA); The second quantity

describes the transfer of energy from the incoming particle to the first atom it encounters in the target, the primary knock-on atom (PKA); The second quantity  is the total number of displacements that the PKA goes on to make in the solid; Taken together, they describe the total number of displacements caused by an incoming particle of energy

is the total number of displacements that the PKA goes on to make in the solid; Taken together, they describe the total number of displacements caused by an incoming particle of energy  , and the above equation accounts for the energy distribution of the incoming particles. The result is the total number of displacements in the target from a flux of particles with a known energy distribution.

, and the above equation accounts for the energy distribution of the incoming particles. The result is the total number of displacements in the target from a flux of particles with a known energy distribution.

In radiation material Science the displacement damage in the alloy ( ![\left[ dpa \right]](../I/m/4cb69cd5b66b393639da0b22b58f1f92.png) = displacements per atom in the solid ) is a better representation of the effect of irradiation on materials properties than the fluence ( neutron fluence,

= displacements per atom in the solid ) is a better representation of the effect of irradiation on materials properties than the fluence ( neutron fluence, ![\left[ MeV \right]](../I/m/afca65b6148fc323a5cb7dd2b6f17cad.png) ).

).

Resource

- Fundamentals of Radiation Material Science, Gary S. Was, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2007

- R. S. Averback and T. Diaz de la Rubia (1998). "Displacement damage in irradiated metals and semiconductors". In H. Ehrenfest and F. Spaepen. Solid State Physics 51. Academic Press. pp. 281–402.

- R. Smith, ed. (1997). Atomic & ion collisions in solids and at surfaces: theory, simulation and applications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44022-X.

References

- ↑ A. Meftah et al. (1994). "Track formation in SiO2 quartz and the thermal-spike mechanism". Physical Review B 49 (18): 12457. Bibcode:1994PhRvB..4912457M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.49.12457.

- ↑ C. Trautmann, S. Klaumünzer, H. Trinkaus (2000). "Effect of Stress on Track Formation in Amorphous Iron Boron Alloy: Ion Tracks as Elastic Inclusions". Physical Review Letters 85 (17): 3648. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.3648T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3648.