Rachel's Tomb

| Tomb of Rachel | |

|---|---|

| Kever Rachel Imenu (transliterated from Hebrew) | |

|

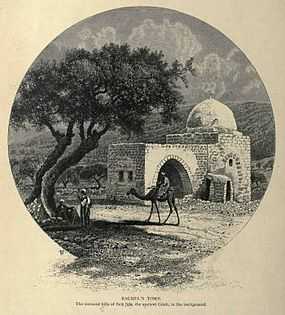

Popular imagery of the tomb depicting it as it appeared during the late 19th century | |

Shown within the West Bank | |

| Location | Bethlehem municipality |

| Region | West Bank |

| Coordinates | 31°43′10″N 35°12′08″E / 31.7193434°N 35.202116°E |

| Type | tomb, prayer area |

| History | |

| Founded | Ottoman |

| Cultures | Jews, Muslims, Christians |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs |

| Public access | Limited |

| Website | keverrachel.com |

| Venerated as the third holiest site in Judaism | |

Rachel's Tomb (Hebrew: קבר רחל translit. Kever Rakhel),[1] also known since the 1990s[2] as the Bilal bin Rabah mosque (Arabic: مسجد بلال بن رباح) to Muslims and UNESCO[3] is the name given to a small religious building[4] encased in concrete[5] revered by Jews, Christians and Muslims.[3][6] The tomb is located within a Muslim cemetery[7] in a walled enclave biting into[8] the outskirts of Bethlehem, 460 meters south of Jerusalem’s municipal boundary,[1] in the West Bank. The burial place of the matriarch Rachel as mentioned in the Jewish and Christian Old Testament, and in Muslim literature[9] is contested between this site and several others to the north.[10] The earliest extra-biblical records describing this tomb as Rachel's burial place date to the first decades of the 4th century AD. The domed structure containing the tomb dates from the Muslim Ottoman period[11] and when Sir Moses Montefiore renovated the site in 1841 after obtaining the key for the Jewish community, he added an antechamber which included a mihrab for Muslim prayer.[4][12] According to the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, the tomb was to be part of the internationally administered zone of Jerusalem, but the area was occupied by Jordan, which prohibited Israelis from entering the area. Though not initially falling within Area C, the site has come under the control of the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs.[13] Rachel's tomb is the third holiest site in Judaism.[14] Jews have made pilgrimage to the tomb since ancient times,[15] and it has become one of the cornerstones of Jewish-Israeli identity.[16]

History

Biblical accounts and disputed location

Biblical scholarship identifies two different traditions in the Hebrew Bible concerning the site of Rachel's burial, respectively a northern version, locating it north of Jerusalem near Ramah, modern Al-Ram, and a southern narrative locating it close to Bethlehem. In rabbinical tradition the duality is resolved by using two different terms in Hebrew to designate these different localities.[17] In the Hebrew version given in Genesis,[18] Rachel and Jacob journey from Shechem to Hebron, a short distance from Ephrath, which is glossed as Bethlehem (35:16-21, 48:7). She dies on the way giving birth to Benjamin:

"And Rachel died, and was buried on the way to Ephrath, which is Bethlehem. And Jacob set a pillar upon her grave: that is the pillar of Rachel's grave unto this day." — Genesis 35:19-20

Tom Selwyn notes that R. A. S. Macalister, the most authoritative voice on the topography of Rachel's tomb, advanced the view in 1912 that the identification with Bethlehem was based on a copyist's mistake.[19] The Judean scribal gloss "(Ephrath, ) which is Bethlehem" was added to distinguish it from a similar toponym Ephrathah in the Bethlehem region. Some consider as certain, however, that Rachel's tomb lay to the north, in Benjamite, not in Judean territory, and that the Bethlehem gloss represents a Judean appropriation of the grave, originally in the north, to enhance Judah's prestige.[20][21][22] At 1 Samuel 10:2, Rachel's tomb is located in the 'territory of Benjamin at Zelzah.' In the period of the monarchy down to the exile, it would follow, Rachel's tomb was thought to lie in Ramah.[23] The indications for this are based on 1 Sam 10:2 and Jer. 31:15, which give an alternative location north of Jerusalem, in the vicinity of ar-Ram, biblical Ramah,[24] five miles south of Bethel.[25] One conjecture is that before David's conquest of Jerusalem, the ridge road from Bethel might have been called "the Ephrath road" (derek ’eprātāh. Gen:35:19;derek’eprāt, Gen: 48:7), hence the passage in Genesis meant 'the road to Ephrath or Bethlehem,' on which Ramah, if that word refers to a toponym,[26] lay.[27] A possible location in the Ramah could be the five stone monuments north of Hizma. Known as Qubur Beni Isra'in, the largest so-called tomb of the group, the function of which is obscure, has the name Qabr Umm beni Isra'in, that is, "tomb of the mother of the descendants of Israel".[28]

Medieval period

| “ | The tomb of Rachel the Righteous is at a distance of 1½ miles from Jerusalem, in the middle of the field, not far from Bethlehem, as it says in the Torah. On Passover and Lag B'Omer many people – men and women, young and old – go out to Rachel's Tomb on foot and on horseback. And many pray there, make petitions and dance around the tomb and eat and drink. | ” |

| —Rabbi Moses Surait of Prague, 1650.[29] | ||

In Jewish lore, Rachel was born on 11 Cheshvan 1553 BC.[30] Traditions regarding the tomb at this location date back to the beginning of the 4th century AD.[31] Eusebius and the Bordeaux Pilgrim mention the tomb as being located 4 miles from Jerusalem.[7] In the late 7th century, the tomb was marked with a stone pyramid, devoid of any ornamentation.[7][32] During the 10th century, Muqaddasi and other geographers fail to mention the tomb which indicates that it may have lost importance until the Crusaders revived its veneration.[7] Muhammad al-Idrisi (1154) writes, "Half-way down the road [between Bethlehem and Jerusalem] is the tomb of Rachel (Rahil), the mother of Joseph and of Benjamin, the two sons of Jacob peace upon them all! The tomb is covered by twelve stones, and above it is a dome vaulted."[33] Benjamin of Tudela (1169–71) mentions a pillar made of 11 stones and a cupola resting on four columns "and all the Jews that pass by carve their names upon the stones of the pillar." Petachiah of Regensburg explains that the 11 stones represented the tribes of Israel, excluding Benjamin, since Rachel had died during his birth. All were marble, with that of Jacob on top."[31] In the 14th century, Antony of Cremona referred to the cenotaph as "the most wonderful tomb that I shall ever see. I do not think that with 20 pairs of oxen it would be possible to extract or move one of its stones." It was described by Franciscan pilgrim Nicolas of Poggibonsi (1346–50) as being 7 feet high and enclosed by a rounded tomb with three gates.

From around the 15th century onwards, if not earlier, the tomb was occupied and maintained by the Muslim rulers.[31] The Russian deacon Zozimos describes it as being a mosque in 1421.[31] A guide published in 1467 credits Shahin al-Dhahiri with the building of a cupola, cistern and drinking fountain at the site.[31] The Muslim rebuilding of the "dome on four columns" was also mentioned by Francesco Suriano in 1485.[31] Felix Fabri (1480–83) described it as being "a lofty pyramid, built of square and polished white stone";[31] He also noted a drinking water trough at its side and reported that "this place is venerated alike by Muslims, Jews, and Christians".[34] Bernhard von Breidenbach of Mainz (1483) described women praying at the tomb and collecting stones to take home, believing that they would ease their labour.[35][36] Pietro Casola (1494) described it as being "beautiful and much honoured by the Moors."[37] Mujir al-Din al-'Ulaymi (1495), the Jerusalemite qadi and Arab historian, writes under the heading of Qoubbeh Râhîl ("Dome of Rachel") that Rachel's tomb lies under this dome on the road between Bethlehem and Bayt Jala and that the edifice is turned towards the Sakhrah (the rock inside the Dome of the Rock) and widely visited by pilgrims.[38] Rabbi Moses Surait of Prague (1650) described a high dome on the top of the tomb, an opening on one side, and a big courtyard surrounded by bricks. He also described a local Jewish cult associated with the site.[29]

Ottoman period

WHICH WAS BUILT BY THE GREAT PRINCE OF ISRAEL

SIR MOSES MONTEFIORE

MAY HIS LIGHT SHINE FORTH

AND HIS WIFE, THE DAUGHTER OF KINGS

LADY JUDITH

MAY WE MERIT TO SEE THE RIGHTEOUS MESSIAH

GOD WILLING, AMEN

In 1615 Muhammad Pasha of Jerusalem repaired the structure and transferred exclusive ownership of the site to the Jews.[39] In 1626, Franciscus Quaresmius visited the site and found that the tomb had been rebuilt by the locals several times. He also found near it a cistern and many Muslim graves.[31] In March 1756, the Istanbul Jewish Committee for the Jews of Palestine instructed that 500 kurus used by the Jews of Jerusalem to fix a wall at the tomb were to be repaid and used instead for more deserving causes.[40] In 1788, walls were built to enclose the arches.[39] According to Richard Pococke, this was done to "hinder the Jews from going into it". Pococke also reports that the site was highly regarded by Turks as a place of burial.[31] An 1824 report described "a stone building, evidently of Turkish construction, which terminates at the top in a dome. Within this edifice is the tomb. It is a pile of stones covered with white plaster, about 10 feet long and nearly as high. The inner wall of the building and the sides of the tomb are covered with Hebrew names, inscribed by Jews."[41]

When the structure was undergoing repairs in around 1825, excavations at the foot of the monument revealed that it was not built directly over an underground cavity. However, a small distance from the site, an unusually deep cavern was discovered.[42]

In 1830, the Ottomans legally recognized the tomb as a Jewish holy site. Proto-Zionist banker Sir Moses Montefiore visited Rachel's Tomb together with his wife on their first visit to the Holy Land in 1828. The couple were childless, and Lady Montefiore was deeply moved by the tomb, which was in good condition at that time. Before the couple's next visit, in 1839, the Galilee earthquake of 1837 had heavily damaged the tomb.[43] In 1838 the tomb was described as "merely an ordinary Muslim Wely, or tomb of a holy person; a small square building of stone with a dome, and within it a tomb in the ordinary Muhammedan form; the whole plastered over with mortar. It is neglected and falling to decay; though pilgrimages are still made to it by the Jews. The naked walls are covered with names in several languages; many of them Hebrew."[32]

In 1841, Montefiore purchased the site and obtained for the Jews the key of the tomb. He renovated the entire structure, reconstructing and re-plastering its white dome.[44][45] He extended the building by constructing an adjacent vaulted ante-chamber on the east for Muslim prayer use and burial preparation, possibly as an act of conciliation.[46] The room included a mihrab facing Mecca.[31][39] In 1843, Ridley Haim Herschell described the building as an ordinary Muslim tomb. He reported that Jews, including Montefiore, were obliged to remain outside the tomb, and prayed at a hole in the wall, so that their voices enter into the tomb.[47] In the mid-1850s, the marauding Arab e-Ta'amreh tribe forced the Jews to furnish them with an annual £30 payment to prevent them from damaging the tomb.[48][49]

According to Elizabeth Anne Finn, wife of the British consul, James Finn the only time the Sephardi Jewish community left the Old City of Jerusalem was for monthly prayers at "Rachel's Sepulchre" or Hebron.[50]

In 1864, the Jews of Bombay donated money to dig a well. Although Rachel's Tomb was only an hour and a half walk from the Old City, many pilgrims found themselves very thirsty and unable to obtain fresh water. Every Rosh Chodesh, the Maiden of Ludmir would lead her followers to Rachel’s tomb and lead a prayer service with various rituals, which included spreading out requests of the past four weeks over the tomb. On the traditional anniversary of Rachel’s death, she would lead a solemn procession to the tomb where she chanted psalms in a night-long vigil.[51]

The Hebrew monthly ha-Levanon of August 19, 1869, rumored that a group of Christians had purchased land around the tomb and were in the process of demolishing Montefiore's vestibule in order to erect a church there.[52] During the following years, land in the vicinity of the tomb was acquired by Nathan Strauss. In October 1875, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer purchased three dunams of land near the tomb intending to establish a Jewish farming colony there.[53] Custody of the land was transferred to the Perushim community in Jerusalem.[53] (During the first years of the Intifada, the Gush Etzion Regional Council managed to buy back ownership of about 10 dunams of Jewish-owned land near the tomb.)[54] In the 1880s, Conder and Kitchener observed Jewish graves near the tomb.[55]

In 1912 the Ottoman Government permitted the Jews to repair the shrine itself, but not the antechamber.[56] In 1915 the structure had four walls, each about 7 m (23 ft.) long and 6 m (20 ft.) high. The dome, rising about 3 m (10 ft.), "is used by the Moslems for prayer; its holy character has hindered them from removing the Hebrew letters from its walls."[57]

British Mandate period

Three months after the British occupation of Palestine the whole place was cleaned and whitewashed by the Jews without protest from the Muslims. However, in 1921 when the Chief Rabbinate applied to the Municipality of Bethlehem for permission to perform repairs at the site, local Muslims objected.[56] In view of this, the High Commissioner ruled that, pending appointment of the Holy Places Commission provided for under the Mandate, all repairs should be undertaken by the Government. However, so much indignation was caused in Jewish circles by this decision that the matter was dropped, the repairs not being considered urgent.[56] In 1925 the Sephardic Jewish community requested permission to repair the tomb. The building was then made structurally sound and exterior repairs were effected by the Government, but permission was refused by the Jews (who had the keys) for the Government to repair the interior of the shrine. As the interior repairs were unimportant, the Government dropped the matter, in order to avoid controversy.[56] In 1926 Max Bodenheimer blamed the Jews for the letting one of their holy sites appear so neglected and uncared for.[58]

During this period, both Jews and Muslims visited the site. From the 1940s, it came to be viewed as a symbol of the Jewish people's return to Zion, to its ancient homeland,[59] For Jewish women, the tomb was associated with fertility and became a place of pilgrimage to pray for successful childbirth.[60][61] Depictions of the Tomb of Rachel have appeared in Jewish religious books and works of art. Muslims prayed inside the mosque there and the cemetery at the tomb was the main Muslim cemetery in the Bethlehem area. The building was also used for Islamic funeral rituals. It is reported that Jews and Muslims respected each other and accommodated each other's rituals.[4] During the riots of 1929, violence hampered regular visits by Jews to the tomb. In the same year, the Waqf demanded control of the site, claiming it was part of the neighboring Muslim cemetery. It also demanded to renew the old Muslim custom of purifying corpses in the tomb's antechamber.[62]

Jordanian period

Following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War till 1967, the site was occupied by Jordan and occupied by the Islamic waqf. On December 11, 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194 which called for free access to all the holy places in Israel and the remainder of the territory of the former Palestine Mandate of Great Britain. In April 1949, the Jerusalem Committee prepared a document for the UN Secretariat in order to establish the status of the different holy places in the area of the former British Mandate for Palestine. It noted that ownership of Rachel's Tomb was claimed by both Jews and Muslims. The Jews claimed possession by virtue of a 1615 firman granted by the Pasha of Jerusalem which gave them exclusive use of the site and that the building, which had fallen into decay, was entirely restored by Moses Montefiore in 1845; the keys were obtained by the Jews from the last Muslim guardian at this time. The Muslims claimed the site was a place of Muslim prayer and an integral part of the Muslim cemetery within which it was situated. They stated that the Ottoman Government had recognised it as such and that it is included among the Tombs of the Prophets for which identity signboards were issued by the Ministry of Waqfs in 1898. They also asserted that the antechamber built by Montefiore was specially built as a place of prayer for Muslims. The UN ruled that the status quo, an arrangement approved by the Ottoman Decree of 1757 concerning rights, privileges and practices in certain Holy Places, apply to the site.[56]

In theory, free access was to be granted as stipulated in the 1949 Armistice Agreements, though Israelis, unable to enter Jordan, were prevented from visiting.[63] Non-Israeli Jews, however, continued to visit the site.[4] During this period the neighbouring Muslim cemetery was expanded, enveloping the immediate area surrounding the tomb.[39]

Israeli control

Following the Six Day War in 1967, Israel gained control of the West Bank, which included the tomb. The tomb was placed under Israeli military administration. Some time after the capture, Islamic crescents, inscribed into the rooms of the structure, were erased. Muslims claim that they were prevented from using the mosque, although they were allowed to use the cemetery for a while.[4]

Prime minister Levi Eshkol instructed that the tomb be included within the new expanded municipal borders of Jerusalem,[54] but citing security concerns, Moshe Dayan decided not to include it within the territory that was annexed to Jerusalem.[64] Starting in 1993, Muslims were barred from using the cemetery.[4] According to Bethlehem University, "[a]ccess to Rachel’s Tomb is now restricted to tourists entering from Israel."[65]

Oslo Accords and aftermath (1995–2002)

Following the Oslo accords, the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement was signed on September 28, 1995,[66] placing Rachel's Tomb in Area C under Israeli jurisdiction. Originally, Yitzhak Rabin had decided to cede Rachel's Tomb, along with Bethlehem.[67] Israel's first draft had placed Rachel's Tomb, which is situated 460 metres from the municipal border of Jerusalem, in Area A under PA jurisdiction. Popular pressure exerted by religious parties in Israel to keep the religious site under Israeli control threatened the agreement, and Yassir Arafat agreed to forego the request.[67][64][68]

On December 1, 1995, Bethlehem, with the exception of the tomb enclave, passed under the full control of the Palestinian Authority. Jews could reach it in bulletproof vehicles under military supervision.[66] In 1996 Israel began an 18-month fortification of the site at a cost of $2m. It included a 13 foot high wall and adjacent military post.[69] In response, Palestinians said that "the Tomb of Rachel was on Islamic land" and that the structure was in fact a mosque built at the time of the Arab conquest in honour of Bilal ibn Rabah, an Ethiopian known in Islamic history as the first muezzin.

After an attack on Joseph's Tomb and its subsequent takeover by Arabs, hundreds of residents of Bethlehem and the Aida refugee camp, led by the Palestinian Authority-appointed governor of Bethlehem, Muhammad Rashad al-Jabari, attacked Rachel's Tomb. They set the scaffolding that had been erected around it on fire and tried to break in. The IDF dispersed the mob with gunfire and stun grenades, and dozens were wounded.[66] In the following years, the Israeli-controlled site became a flashpoint between young Palestinians who hurled stones, bottles and firebombs and IDF troops, who responded with tear gas and rubber bullets.[70]

At the end of 2000, when the second intifada broke out, the tomb came under attack for 41 days. Fatah operatives and members of the Palestinian security services who were responsible for curbing militant activity against Israelis actively participated in it. In May 2001, fifty Jews found themselves trapped inside by a firefight between the IDF and Palestinian Authority gunmen. In March 2002 the IDF returned to Bethlehem as part of Operation Defensive Shield and remained there for an extended period of time.[66] In September 2002, the tomb was incorporated on the Israeli side of the West Bank barrier and surrounded by a concrete wall and watchtowers.

In February 2005, the Israel Supreme Court rejected a Palestinian appeal to change the route of the security fence in the region of the tomb.[66] Israeli construction destroyed the Palestinian neighbourhood of Qubbet Rahil. Israel also declared the area to be a part of Jerusalem.[4]

In February 2010, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu announced that the tomb would become a part of the national Jewish heritage sites rehabilitation plan.[71] The decision was opposed by the Palestinian Authority, who saw it as a political decision associated with Israel's settlement project.[3] The UN's special coordinator for the Middle East, Robert Serry, issued a statement of concern over the move, saying that the site is in Palestinian territory and has significance in both Judaism and Islam.[72] The Jordanian government said that the move would derail peace efforts in the Middle East and condemned "unilateral Israeli measures which affect holy places and offend sentiments of Muslims throughout the world".[72] UNESCO urged Israel to remove the site from its heritage list, stating that it was "an integral part of the occupied Palestinian territories". A resolution was passed at UNESCO that acknowledged both the Jewish and Islamic significance of the site, describing the site as both Bilal ibn Rabah Mosque and as Rachel's Tomb.[3] The resolution passed with 44 countries supporting it, twelve countries abstaining, and only the United States voting to oppose.[3] An article written by Nadav Shargai of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, published in the Jerusalem Post criticized UNESCO, arguing that the site was not a mosque and that the move was politically motivated to disenfranchise Israel and Jewish religious traditions.[1] Also writing in the Jerusalem Post, Larry Derfner, defended the UNESCO position. He pointed out that UNESCO had explicitly recognized the Jewish connection to the site, having only denounced Israeli claims of sovereignty, while also acknowledging the Islamic and Christian significance of the site.[73] The Israeli Prime Minister's Office criticised the resolution, claiming that: "the attempt to detach the Nation of Israel from its heritage is absurd... If the nearly 4,000-year-old burial sites of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of the Jewish Nation – Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah – are not part of its culture and tradition, then what is a national cultural site?”[74][75]

Jewish religious significance

Rabbinic traditions

- According to the Midrash, the first person to pray at Rachel's tomb was her eldest son, Joseph. While he was being carried away to Egypt after his brothers had sold him into slavery, he broke away from his captors and ran to his mother's grave. He threw himself upon the ground, wept aloud and cried "Mother! mother! Wake up. Arise and see my suffering." He heard his mother respond: "Do not fear. Go with them, and God will be with you."[76]

- A number of reasons are given why Rachel was buried by the road side and not in the Cave of Machpela with the other Patriarchs and Matriarchs:

- Jacob foresaw that following the destruction of the First Temple the Jews would be exiled to Babylon. They would cry out as they passed her grave, and be comforted by her. She would intercede on their behalf, asking for mercy from God who would hear her prayer.[77]

- Although Rachel was buried within the boundaries of the Holy Land, she was not buried in the Cave of Machpelah due to her sudden and unexpected death. Jacob, looking after his children and herds of cattle, simply did not have the opportunity to embalm her body to allow for the slow journey to Hebron.[78][79]

- Jacob was intent on not burying Rachel at Hebron, as he wished to prevent himself feeling ashamed before his forefathers, lest it appear he still regarded both sisters as his wives - a biblically forbidden union.[79]

- According to the mystical work, Zohar, when the Messiah appears, he will lead the dispersed Jews back to the Land of Israel, along the road which passes Rachel's grave.[80]

Location

| “ | Even now the [Jews] go there every Thursday to pray and read the old, old history of this mother of their race… I met a hundred or more Jews on their weekly visit to the venerated spot. | ” |

| —Paulist Fathers, 1868.[81] | ||

Early Jewish scholars noticed an apparent contradiction in the Bible with regards to the location of Rachel's grave. In Genesis, the Bible states that Rachel was buried "on the way to Ephrath, which is Bethlehem." Yet a reference to her tomb in Samuel states: "When you go from me today, you will find two men by Rachel's tomb, in the border of Benjamin, in Zelzah" (1 Sam 10:2). Rashi asks: "Now, isn't Rachel's tomb in the border of Judah, in Bethlehem?" He explains that the verse rather means: "Now they are by Rachel's tomb, and when you will meet them, you will find them in the border of Benjamin, in Zelzah." Similarly, Ramban assumes that the site shown today near Bethlehem reflects an authentic tradition. After he had arrived in Jerusalem and seen "with his own eyes" that Rachel's tomb was on the outskirts of Bethlehem, he retracted his original understanding of her tomb being located north of Jerusalem and concluded that the reference in Jeremiah (Jer 31:15) which seemed to place her burial place in Ramah, is to be understood allegorically. There remains however, a dispute as to whether her tomb near Bethlehem was in the tribal territory of Judah, or of her son Benjamin.[82]

Jewish customs

Rachel is considered the "eternal mother", caring for her children when they are in distress especially for barren or pregnant woman. Jewish tradition teaches that Rachel weeps for her children and that when the Jews were taken into exile, she wept as they passed by her grave on the way to Babylonia. Jews have made pilgrimage to the tomb since ancient times.[15]

There is a tradition regarding the key that unlocked the door to the tomb. The key was about 15 centimetres (5.9 in) long and made of brass. The beadle kept it with him at all times, and it was not uncommon that someone would knock at his door in the middle of the night requesting it to ease the labor pains of an expectant mother. The key was placed under her pillow and almost immediately, the pains would subside and the delivery would take place peacefully.

Till this day there is an ancient tradition regarding a segulah or charm which is the most famous women's ritual at the tomb.[83] A red string is tied around the tomb seven times then worn as a charm for fertility.[83] This use of the string is comparatively recent, though there is a report of its use to ward off diseases in the 1880s.[84]

The Torah Ark in Rachel's Tomb is covered with a curtain (Hebrew: parokhet) made from the wedding gown of Nava Applebaum, a young Israeli woman who was killed by a Palestinian terrorist in a suicide bombing at Café Hillel in Jerusalem in 2003, on the eve of her wedding.[85]

Replicas

The tomb of Sir Moses Montefiore, adjacent to the Montefiore synagogue in Ramsgate, England, is a replica of Rachel's Tomb. During an 1841 visit to Palestine, Montifiore obtained permission from the Ottoman Turks to restore the tomb.[86]

In 1934, the Michigan Memorial Park planned to reproduce the tomb. When built, it was used to house the sound system and pipe organ used during funerals, but it has since been demolished.[87]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Jerusalem post". www.jpost.com. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ Shragai, Nadav. "The Palestinian Authority and the Jewish Holy Sites in the West Bank: Rachel’s Tomb as a Test Case". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Carbajosa, Ana (29 October 2010). "Holy site sparks row between Israel and UN". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Tom Selwyn. CONTESTED MEDITERRANEAN SPACES:The Case of Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem, Palestine. Berghahn Books. pp. 276–278.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Mitch (2013-03-22). "On Obama's path to Bethlehem, a harshly fortified shrine". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ "Israel clashes with UNESCO in row over holy sites". Haaretz. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Moshe Sharon (1999). Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (CIAP). BRILL. p. 177. ISBN 978-90-04-11083-0. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ↑ "Wall annexes Rachel's Tomb, imprisons Palestinian families Israel News". haaretz.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Rachel Weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb - Frederick M. Strickert - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Frederick M. Strickert,Rachel Weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb, Liturgical Press, 2007 pp.68ff.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2000). Georges, Sabagh, ed. Religion and Culture in Medieval Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-521-62350-6.

- ↑ Whittingham, George Napier (1921). The Home of Fadeless Splendour: Or, Palestine of Today. Dutton. p. 314. "In 1841 Montefiore obtained for the Jews the key of the Tomb, and to conciliate Moslem susceptibility, added a square vestibule with a mihrab as a place of prayer for Moslems."

- ↑ Michael Dumper, The Politics of Sacred Space: The Old City of Jerusalem in the Middle East Conflict, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002p.147.

- ↑ Israel yearbook on human rights, Volume 36, Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University, 2006. pg. 324

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Martin Gilbert (3 September 1985). Jerusalem: rebirth of a city. Viking. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-670-80789-5. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

Rachel’s tomb has been a place of Jewish pilgrimage even before the Roman destruction of Jerusalem.

- ↑ Meron Benvenisti, Son of the Cypresses: Memories, Reflections, and Regrets from a Political Life,University of California Press, 2007 p.45.

- ↑ Frederick+ Strickert, Rachel Weeping, pp.57,64.

- ↑ In the Septuagint translation, Bethlehem is also given but the order of the verses is changed because of geographical difficulties. F.Strickert, p.20.

- ↑ Tom Selwyn, 'Tears on the Border: The Case of Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem, Palestine,' in Maria Kousis, Tom Selwyn, David Clark, (eds.)Contested Mediterranean Spaces: Ethnographic Essays in Honour of Charles Tilly, Berghahn Books 2011 pp. 276-295, p.279:'Macalister claims that in the earliest versions of Genesis it is written .. that Rachel was buried in Ephrathah, not Ephrath, and that this name refers to the village of Ramah, now er-Ram, near Himzeh to the north of Jerusalem.'

- ↑ Zecharia Kallai, 'Rachel's Tomb: A Historiographical Review,' in Vielseitigkeit des Altes Testaments, Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1999 pp.215-223.

- ↑ Jules Francis Gomes, The Sanctuary of Bethel and the Configuration of Israelite Identity, Walter de Gruyter, 2006 p.92

- ↑ J.Blenkinsopp, 'Benjamin Traditions read in the Early Persian Period,' in Oded Lipschitz, Manfred Oeming (eds.), Judah and the Judeans in the Persian period, Eisenbrauns, 2006 pp.629-646 p.630-31. ISBN 1-57506-104-X

- ↑ Friederich Strickert, Rachel Weeping,pp.61-2:'one must conclude that Rachel's tomb was located near Ramah.'; 'During the time of the monarchy, from the anointing of Saul to the beginning of exile (1040-596 B.C.E.), Rachel's tomb was understood to be located in the north near Ramah.'

- ↑ Blenkinsopp, p.630-1.

- ↑ Jules Francis Gomes,The Sanctuary of Bethel and the Configuration of Israelite Identity, p.135:'Rachel's tomb was originally on the border between Benjamin and Joseph. It was later located in Bethlehem as in the gloss on Gen.35:19.

- ↑ ramah means 'a height'. Most scholars take it to refer to a place-name. Martien Halvorson-Taylor, Enduring Exile: The Metaphorization of Exile in the Hebrew Bible, BRILL 2010 p.75, n.62, thinks the evidence for this is weak, but argues the later witness of Genesis for Bethlehem as Rachel's burial site 'an even more dubious witness to its location'.

- ↑ David Toshio Tsumura,The First Book of Samuel, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007 p.284.

- ↑ Strickert, p. 69.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Susan Sereď, Our Mother Rachel, in Arvind Sharma, Katherine K. Young (eds.). The Annual Review of Women in World Religions, Volume 4, SUNY Press, 1991, p. 21–24. ISBN 0-7914-2967-9

- ↑ Jewish Calendar, Passing of Rachel, Chabad.org.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 31.9 Pringle, Denys. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 176. ISBN 0-521-39037-0

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Edward Robinson, Eli Smith. Biblical researches in Palestine and the adjacent regions: a journal of travels in the years 1838 & 1852, Volume 1, J. Murray, 1856. p. 218.

- ↑ le Strange, 1890, p.299.

- ↑ The book of Wanderings of Brother Felix Fabri. I, part II. Palestine Pilgrims Text Society. 1896. p. 547. archive.org

- ↑ Ruth Lamdan (2000). A separate people: Jewish women in Palestine, Syria, and Egypt in the sixteenth century. BRILL. p. 84. ISBN 978-90-04-11747-1. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ Reflections of God's Holy Land: A Personal Journey Through Israel, Thomas Nelson Inc, 2008. p. 57. ISBN 0-8499-1956-8

- ↑ "Further on, near to Bethlehem, I saw the sepulchre of Rachel, the wife of the Patriarch Jacob, who died in childbirth. It is beautiful and much honoured by the Moors.". Archive.org. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ ed-Dyn, 1876, p. 202.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin Gitlitz. Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 511. ISBN 1-57607-004-2

- ↑ Strickert, p. 111.

- ↑ The religious miscellany: Volume 3 Fleming and Geddes, 1824, p. 150

- ↑ Schwarz, Joseph. Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine, 1850. "It was always believed that this stood over the grave of the beloved wife of Jacob. But about twenty-five years ago, when the structure needed some repairs, they were compelled to dig down at the foot of this monument; and it was then found that it was not erected over the cavity in which the grave of Rachel actually is; but at a little distance from the monument there was discovered an uncommonly deep cavern, the opening and direction of which was not precisely under the superstructure in question."

- ↑ Strickert, pp. 112-3.

- ↑ George Frederick Owen (1 July 1977). The Holy Land. Beacon Hill Press of Kansas City. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8341-0489-1. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

In 1841, Sir M. Montefiore purchased the grounds and monument for the Jewish community, added an adjoining prayer vestibule, and reconditioned the entire structure with its white dome and quiet reception or prayer room.

- ↑ In 1845, Montefiore made further architectural improvements at the tomb. Susan Sereď, Our Mother Rachel, in Arvind Sharma, Katherine K. Young (eds.). The Annual Review of Women in World Religions, Volume 4, SUNY Press, 1991, p. 21–24. ISBN 0-7914-2967-9

- ↑ Whittingham, George Napier. The home of fadeless splendour: or, Palestine of today, Dutton, 1921. pg. 314. "In 1841 Montefiore obtained for the Jews the key of the Tomb, and to conciliate Moslem susceptibility, added a square vestibule with a mihrab as a place of prayer for Moslems."

- ↑ Ridley Haim Herschell (1844). A visit to my father-land: being notes of a journey to Syria and Palestine in 1843. Unwin. p. 191. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ↑ Menashe Har-El (April 2004). Golden Jerusalem. Gefen Publishing House Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 978-965-229-254-4. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ↑ Edward Everett; James Russell Lowell; Henry Cabot Lodge (1862). The North American review. O. Everett. p. 336. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

The annual expenses of the Sepharedim…are reckoned to be…5,000 [piasters] for the liberty of visiting Rachel's tomb near Bethlehem [paid as a "backshish" to the Turks for the privilege].

- ↑ Jerusalem in the 19th Century: The Old City, Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi & St. Martin's Press, 1984, pp.286-287.

- ↑ Nathaniel Deutsch (6 October 2003). The maiden of Ludmir: a Jewish holy woman and her world. University of California Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-520-23191-7. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ↑ Mekhon Shekhṭer le-limude ha-Yahadut; International Research Institute on Jewish Women (1998). Nashim: a journal of Jewish women's studies & gender issues. Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies. p. 12. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Arnold Blumberg (August 1998). The history of Israel. Greenwood Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-313-30224-4. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Shragai, Nadav. The Palestinians who are shooting at the Rachel's Tomb compound have already singled it out as the next Jewish holy site which they want to 'liberate', Haaretz, (October 31, 2000)

- ↑ C. R. Conder and H. H. Kitchener (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine III. London: The Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 129.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 United Nations Conciliation Commission For Palestine: Committee on Jerusalem. (April 8, 1949)

- ↑ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q-Z, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995 (reprint), [1915]. p. 32. ISBN 0-8028-3784-0

- ↑ Max Bodenheimer (1963). Prelude to Israel: the memoirs of M. I. Bodenheimer. T. Yoseloff. p. 327. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

The grave of Rachel left me with nothing but sorrowful recollection. It is regrettable that the Jews so neglect their holy places, while in the vicinity of monasteries and of Christian and Moslem places of pilgrimage one finds well-kept gardens. Why does Rachel's tomb lie bare, somber and neglected in a stony desert? As there can be no lack of money about, it can be assumed that the Jews, during the long exile of the Ghetto, lost all sense of beauty and of the significance of impressive monuments and the possibility of surrounding them with gardens.

- ↑ Susan Sered, "A Tale of Three Rachels: The Natural Herstory of a Cultural Symbol," in Nashim: a journal of Jewish women's studies & gender issues, Issues 1-2, Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, 1998. "In the 1940s, by contrast, Rachel's Tomb became explicitly identified with the return to Zion, Jewish statehood and Allied victory."

- ↑ Margalit Shilo (2005). Princess or prisoner?: Jewish women in Jerusalem, 1840-1914. UPNE. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-58465-484-1. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ↑ Jill Dubisch, Michael Winkelman, Pilgrimage and Healing, University of Arizona Press, 2005 p.75.

- ↑ Shragai, Nadav. The Palestinians Invent a Religious Claim: Rachel's Tomb termed "Bilal ibn", (December 2, 2007)

- ↑ Daniel Jacobs, Shirley Eber, Francesca Silvani. Israel and the Palestinian territories, Rough Guides, 1998. p. 395. ISBN 1-85828-248-9

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Benveniśtî, Mêrôn. Son of the cypresses: memories, reflections, and regrets from a political life, University of California Press, 2007, P.44-45. ISBN 0-520-23825-7

- ↑ "Bethlehem University Research Project Explores Importance of Rachel's Tomb." Bethlehem University. 4 May 2009. 25 March 2012.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 Shragai, Nadav (2011). "Institute for Contemporary Affairs - Wechsler Family Foundation - Palestinians - Palestinian Authori". jcpa.org. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Nahum Barnea, 'The battle for Jerusalem,' Ynet, 10 November 2014.

- ↑ Thousands at burial of Rabbi Menahem Porush, Jerusalem Post, (February 23, 2010)

- ↑ Strickert, p. 135.

- ↑ Unrest during the late 1990s:

- Capital braces for violence, Jerusalem Post, (March 21, 1997).

- Israelis, Arabs clash in protest near Rachel's tomb, The Deseret News, (May 30, 1997).

- Palestinians stone soldiers by Rachel's Tomb, Jerusalem Post, (August 24, 1997).

- More West Bank Tension As Envoy Meets Arafat, New York Times, (September 13, 1998).

- ↑ "US slams Israel over designating heritage sites". Associated Press. 2010-02-24.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "UN: Israel 'heritage sites' are on Palestinian land". Haaetz. 2010-02-22.

- ↑ "Rattling The Cage: UNESCO is right, Israel is wrong". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ "UNESCO Erases Israeli Protests from Rachel's Tomb Protocol". Israelnationalnews.com. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ PM insists Rachel's Tomb is heritage site, Ynet, 10/29/2010

- ↑ "Rachel's Tomb - - Israel". Chabad.org. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Bryna Jocheved Levy (April 2008). Waiting for Rain: Reflections at the Turning of the Year. Jewish Publication Society. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8276-0841-2. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ↑ Baḥya ben Asher ben Ḥlava; Eliyahu Munk (1998). Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya, Torah Commentary: Toldot-Vayeshi (pages 385-738). Sole North American distributor, Lampda Publishers. p. 690. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Ramban. Genesis, Volume 2. Mesorah Publications Ltd, 2005. pp. 545-47.

- ↑ Strickert, p. 32.

- ↑ Paulist Fathers (1868). Catholic world. Paulist Fathers. p. 464. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ Ramban. Genesis, Volume 2. Mesorah Publications Ltd, 2005. p. 247.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Susan Sered, "Rachel's Tomb and the Milk Grotto of the Virgin Mary: Two Women's Shrines in Bethlehem", Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, vol 2, 1986, pp. 7–22.

- ↑ Susan Sered, "Rachel's Tomb: The Development of a Cult", Jewish Studies Quarterly, vol 2, 1995, pp. 103–148.

- ↑ Review of The Story of Rachel's Tomb, Joshua Schwartz, Jewish Quarterly Review 97.3 (2007) e100-e103

- ↑ Sharman Kadish, Jewish Heritage in England : An Architectural Guide, English Heritage, 2006, p. 62

- ↑ Hershenzon, Gail D. (2007). Michigan Memorial Park. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 40–42. ISBN 9780738551593.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rachel's Tomb. |

- ed-dyn, Moudjir (1876). Sauvaire, ed. Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn.

- Gitlitz, David M. & Linda Kay Davidson. “Pilgrimage and the Jews’’ (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006).

- le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London, (Muhammad al-Idrisi: p.299)

- Sharon, Moshe (1999), Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Vol. II, B-C, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-11083-6 (p.177, ff)

- Strickert, Frederick M. (2007), Rachel weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb, Liturgical Press, ISBN 0-8146-5987-X

External links

- Rachel's Tomb Website General Info., History, Pictures, Video, Visitor Info., Transportation

- Is this Rachel’s Tomb? A geographical and historical review

- A site dedicated to Rachel's Tomb

- Rachel's Tomb, a Jewish Holy Place, Was Never a Mosque

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||