Race in the United States criminal justice system

There have been different outcomes for different racial groups in convicting and sentencing felons in the United States criminal justice system.[1][2] Experts and analysts have debated the relative importance of different factors that have led to these disparities.[3][4] Minority defendants are charged with crimes requiring a mandatory minimum prison sentence more often, in both relative and absolute terms (depending on the classification of race, mainly in regards to Hispanics), leading to large racial disparities in incarceration.[5]

Racial inequality in incarceration

At the end of 2002 the Bureau of Justice released data stating there were 3,042 black male prisoners per 100,000 black males, 1,261 Hispanic male prisoners per 100,000 Hispanic males and 487 white male prisoners per 100,000 white males within the United States.[1] According to Antonio Moore in his Huffington Post article, "there are more African American men incarcerated in the U.S. than the total prison populations in India, Argentina, Canada, Lebanon, Japan, Germany, Finland, Israel and England combined." There are only 19 million African American males in the United States, collectively these countries represent over 1.6 billion people. [7] There are a total of a mere 18.5 million African American males of all ages in the United States. The Black Male Incarceration Problem is Real and Catastrophic - Huffington Post

Likelihood of incarceration

The likelihood of black males going to prison in their lifetime is 28% compared to 4% for white males and 16% for Hispanic males.[2]

Some factors used to attempt to explain the racial disparities in the criminal justice system besides race itself include socioeconomic status, the environment in which a person was raised, and the highest educational level a person achieves.

For the Baby Boomers, some 1.2% of white men and 9% of black men had been imprisoned by 2004, according to Bruce Western, a Harvard sociology professor.[8] Out of those born in the 1970s, 3.3% of white men and 20.7% of black men had been in prison.[9]

Effect of race on likelihood of conviction

Various studies have shown that, in recent decades, there has been no noticeable disparity in black vs white conviction likelihood for those accused in black-run vs white-controlled cities, say Atlanta vs San Diego. In the largest counties, the rates of prosecution for accused blacks was slightly less than the prosecution rates for whites, for example. "...the only hint of racial disparity was to the advantage, not disadvantage, of blacks accused of crimes."[3]

Race and the death penalty

Various scholars have addressed what they perceived as the systemic racial bias present in the administration of capital punishment in the United States.[10] There is also a large disparity between races when it comes to sentencing convicts to Death Row. The federal death penalty data released by the United States Department of Justice between 1995–2000 shows that 682 defendants were sentenced to death.[11] Out of those 682 defendants, the defendant was black in 48% of the cases, Hispanic in 29% of the cases, and white in 20% of the cases.[3] 52.5% of people who committed homicides in the 1980-2005 time period were black.[12][13]

Contributing factors to the rise in the penal population

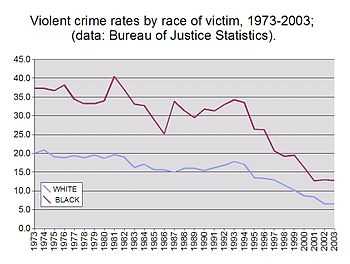

In 2013, the United States had the highest rate of incarceration in the world. In the 1980s U.S. legislation issued a number of new drug laws with stiffer penalties that ranged from drug possession to drug trafficking. Many of those charged with drug crimes saw longer prison sentences and less judicial leniency when facing trial. The War on Drugs has furthered the boom in prison population even though violent crime has continued to steadily decrease.

A lot of urban areas in the U.S. have a majority black population. With crime tendencies high in these areas, drugs are also prevalent. This means that a greater percentage of those in prison are going to be black because law enforcement is already concentrated in the areas with high violent crime and drug crime. With this new drug legislation, the U.S. government has increased the use of incarceration for social control which has resulted in "sharper disproportionate effects on African Americans."[4]

Factors affecting incarceration rates

Blacks had a higher chance of going to prison especially if they drop out of high school. If a Black male dropped out of high school, he had an over 50% chance of being incarcerated in his lifetime, as compared to an 11% chance for White male high school dropouts.[14] Socio-economic, geographic, and educational disparities, as well as alleged unequal treatment in the criminal justice system, contributed to this gap in incarceration rates by race.

Failure to achieve literacy (reading at "grade level") by the third or fourth grade makes the likelihood of future incarceration twenty times more likely than other students. Some states use this measurement to predict how much prison space they will require in the future. It appears to be a poverty issue rather than a race issue.[15]

Effects on families and neighborhoods

With violent crime on the rise in the late 20th century coupled with the war on drugs violations, penal population growth sent shockwaves through the most fragile families and neighborhoods that were least equipped to deal with the problem.[4] Since the majority of people in the prison population are minorities and lower class individuals, the people they leave behind have to deal with extraordinary circumstances. This burden has left families broken and children are the victims of single-parent homes which increases the percentage of these children going to jail earlier than most. With the majority of the prison population being men, "women are left in free society to raise families and contend with ex-prisoners returning home after release."[4]

Children raised in single-parent homes are less supervised which leads to less emphasis on education and self-determination. The result of this situation is that society is damaged and has to take on the financial burden of children growing up in crime ridden neighborhoods and going to prison. When a family member is arrested, the family loses not only that person's income, but also acquire additional expenses involved in keeping contact with the incarcerated family member.[3]

The current prison complex serves as a punitive system in which mass incarceration has become the response to problems in society. Field studies regarding prison conditions describe behavioral changes produced by prolonged incarceration, and conclude that imprisonment undermines the social life of inmates by exacerbating criminality or impairing their capacity for normal social interaction. Moreover, this racial disparity in imprisonment, particularly with African Americans, subjects them to political subordination by destroying their positive connection with society.[16] Institutional factors – such as the prison industrial complex itself – become enmeshed in everyday lives, so much so that prisons no longer function as “law enforcement” systems.[17]

Crime in poorer urban neighborhoods is linked to increased rates of mass incarceration, as job opportunities decline and people turn to crime for survival.[18] Crime among low-education men is often linked to the economic decline among unskilled workers.[18] These economic problems are also tied to reentry into society after incarceration. Data from the Washington State Department of Corrections and Employment Insurance records show how “the wages of black ex-inmates grow about 21 percent more slowly each quarter after release than the wages of white ex-inmates.”[19]

Black ex-inmates earn 10 percent less than white ex-inmates post incarceration.[19]

Black women

Problems resulting from mass incarceration extend beyond economic and political aspects to reach community lives as well. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, 46% of black female inmates were likely to have grown up in a home with only their mothers. A study by Bresler and Lewis shows how incarcerated African American women were more likely to have been raised in a single female headed household while incarcerated white women were more likely to be raised in a two parent household.[20] Black women’s lives are often shaped by the prison system because they have intersecting familial and community obligations. The “increase incarceration of black men and the sex ratio imbalance it induces shape the behavior of young black women.”[21]

Education, fertility, and employment for black women are affected due to increased mass incarceration. Black women’s employment rates were increased, shown in Mechoulan’s data, due to increased education. Higher rates of black male incarceration lowered the odds of nonmarital teenage motherhood and black women’s ability to get an educational degree, thus resulting in early employment.[22] Whether incarcerated themselves or related to someone who was incarcerated, women are often conformed into stereotypes of how they are supposed to behave yet are isolated from society at the same time.[23]

Furthermore, this system can disintegrate familial life and structure. Black and Latino youth are more likely to be incarcerated after coming in contact with the American juvenile justice system. In a study by Victor Rios, 75% of prison inmates in the United States are Black and Latinos between the ages of 20 and 39.[24] Furthermore, societal institutions – such as schools, families, and community centers can impact youth by initiating them into this system of criminalization from an early age. These institutions, traditionally set up to protect the youth, contribute to mass incarceration by mimicking the criminal justice system.[24]

From a different perspective, parents in prison face further moral and emotional dilemmas because they are separated from their children. Both black and white women face difficulty with where to place their children while incarcerated and how to maintain contact with them.[25] According to the study by Bresler and Lewis, black women are more likely to leave their children with related kin whereas white women’s children are likely to be placed in foster care.[25] In a report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics revealed how in 1999, seven percent of black children had a parent in prison, making them nine times more likely to have an incarcerated parent than white children.[16]

Having parents in prison can have adverse psychological effects as children are deprived of parental guidance, emotional support, and financial help.[16] Because many prisons are located in remote areas, incarcerated parents face physical barriers in seeing their children and vice versa. Societal influences, such as low education among African American men, can also lead to higher rates of incarceration. Imprisonment has become “disproportionately widespread among low-education black men” in which the penal system has evolved to be a “new feature of American race and class inequality”.[18] Scholar Pettit and Western’s research has shown how incarceration rates for African Americans are “about eight times higher than those for whites,” and prison inmates have less than “12 years of completed schooling” on average.[18]

Post release

These factors all impact released prisoners who try to reintegrate into society. According to a national study, within three years of release, almost 7 in 10 will have been rearrested. Many released prisoners have difficulty transitioning back into societies and communities from state and federal prisons because the social environment of peers, family, community, and state level policies all impact prison reentry; the process of leaving prison or jail and returning to society. Men eventually released from prison will most likely return to their same communities, putting additional strain on already scarce resources as they attempt to garner the assistance they need to successfully reenter society. Due to the lack of resources, these same men will continue along this perpetuating cycle.[18]

A major challenge for prisoners re-entering society is obtaining employment, especially for individuals with a felony on their record. A study utilizing U.S. Census occupational data in New Jersey and Minnesota in 2000 found that "individuals with felon status would have been disqualified from approximately one out of every 6.5 occupations in New Jersey and one out of every 8.5 positions in Minnesota".[26] As African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately affected by felon status, these additional limitations on employment opportunity were shown to exacerbate racial disparities in the labor market.

See also

- Statistics of incarcerated African-American males

- Race and inequality in the United States

- Legalized abortion and crime effect

- Race and the War on Drugs

- Race and crime

- Racial profiling in the United States

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 United States. Dept. of Justice. 2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Prison Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Justice.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lifetime Likelihood of Going to State or Federal Prison, US Department of Justice, 1997.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Stephan Thernstrom; Abigail Thernstrom (2011-03-29). America in black and white: one nation indivisible. p. 273. Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bobo, Lawrence D., Victor Thompson. 2006. “Unfair By Design: The War on Drugs, Race, and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System.” Social Research 73: 445-472.

- ↑ Rehavi and Starr (2012) "Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Charging and Its Sentencing Consequences" Working Paper Series, no. 12-002 (Univ. of Michigan Law & Economics, Empirical Legal Studies Center)

- ↑ Prison Inmates at Midyear 2009 - Statistical Tables (NCJ 230113). U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. The rates are for adult males, and are from Tables 18 and 19 of the PDF file. Rates per 100,000 were converted to percentages.

- ↑ Antonio Moore (February 23, 2015). The Black Male Incarceration Problem Is Real and It's Catastrophic. The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Londono, O. (2013), A Retributive Critique of Racial Bias and Arbitrariness in Capital Punishment. Journal of Social Philosophy, 44: 95–105. doi: 10.1111/josp.12013

- ↑ Coker, Donna. 2003. “Foreword: Addressing the Real World of Racial Injustice in the Criminal Justice System.” Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 93: 827-879.

- ↑ "Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008" (PDF). p. 3.

- ↑ Cooper, Alexia (2012). Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008. p. 3. ISBN 1249573246.

- ↑ Western, Bruce. 'Punishment and Inequality in America'. New York: Russell, 2006.

- ↑ Rains, Bob (October 8, 2013). "Brevard's new literacy crusade:United Way. Alarming jail, social statistics motivate new priorities". Florida Today (Melbourne, Florida). pp. 5A. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Roberts, Dorothy (2004). "The Social and Moral Cost of Mass Incarceration in African American Communities". Stanford Law Review 56.

- ↑ Roberts, Dorothy (2004). "The Social and Moral Cost of Mass Incarceration in African American Communities". Stanford Law Review (56).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Pettit, B.; Western, B. (1 April 2004). "Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration". American Sociological Review 69 (2): 151–169. doi:10.1177/000312240406900201.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Lyons, Christopher J.; Pettit, Becky (1 May 2011). "Compounded Disadvantage: Race, Incarceration, and Wage Growth". Social Problems 58 (2): 257–280. doi:10.1525/sp.2011.58.2.257.

- ↑ Greene, Susan (1 April 2004). "Mothering and Making It, in and Out of Prison". Punishment & Society 6 (2): 229–233. doi:10.1177/1462474504041269.

- ↑ Mechoulan, Stephane. "The External Effects of black Male Incarceration on Black Females". Journal of Labor Economics (29).

- ↑ Mechoulan, Stephane. "The External Effects of Black Male Incarceration on Black Females". Journal of Labor Economics (29).

- ↑ Phillips, S.; Haas, L. P.; Coverdill, J. E. (15 December 2011). "Disentangling Victim Gender and Capital Punishment: The Role of Media". Feminist Criminology 7 (2): 130–145. doi:10.1177/1557085111427295.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Rios, Victor M. (1 July 2006). "The Hyper-Criminalization of Black and Latino Male Youth in the Era of Mass Incarceration". Souls 8 (2): 40–54. doi:10.1080/10999940600680457.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ferraro, Kathleen J.; Moe, Angela M. (1 February 2003). "Mothering, Crime, And Incarceration". Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 32 (1): 9–40. doi:10.1177/0891241602238937.

- ↑ Wheelock, Darren; Christopher Uggen and Heather Hlvaka. 'Employment Restrictions for Individuals with Felons Status and Racial Inequality in the Labor Market' in 'Global Perspectives on Re-Entry'. Marquette University, 2011.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||