Rabi Island

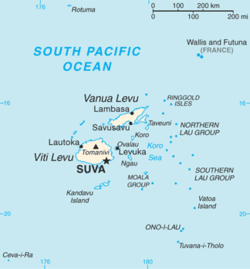

Map of Fiji | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Fiji |

| Coordinates | 16°30′S 180°0′W / 16.500°S 180.000°WCoordinates: 16°30′S 180°0′W / 16.500°S 180.000°W |

| Archipelago | Vanua Levu Group |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Koro Sea |

| Area | 67.3 km2 (26.0 sq mi)[1] |

| Length | 15 km (9.3 mi) |

| Fiji | |

|

Fiji | |

| Division | Northern |

| Province | Cakaudrove |

| Largest settlement | Tabwewa (pop. 600) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 5000 (as of 2014) |

| Density | 74.3 /km2 (192.4 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Banabans 95%, Native Fijians 4%, Other 1% |

Rabi (pronounced [ˈrambi]) is a volcanic island in northern Fiji. It is an outlier to Taveuni (5 kilometers west), in the Vanua Levu Group. It covers an area of 66.3 square kilometers, reaching a maximum altitude of 463 meters and has a shoreline of 46.2 kilometers. With a population of around 5,000, Rabi is home to the Banabans who are the indigenous landowners of Banaba Island; the indigenous Fijian community that formerly lived on Rabi was moved to Taveuni after the island was purchased by the Banabans. The original inhabitants still maintain their links to the island, and still use the Rabi name in national competitions.

Geography

Rabi has four main settlements – all named after, and populated by the descendants of, four villages on Banaba that were destroyed by the invading Japanese forces in the Second World War. Tabwewa Village, formerly known as Nuku in Fijian, is the administrative centre of Rabi. Located in the far north of the island, Tabwewa boasts administrative buildings, a wharf, a post office, court house, a hospital, and a guest house – the only one on the island. 14 kilometers to the south of Tabwewa is Tabiang (formerly Siosio), the home of Rabi's only school and an airstrip. Other major settlements include Uma (formerly Wiinuku), between Tabwewa and Tabiang, and Buakonikai (formerly Aoteqea), some 22 kilometers from Tabwewa. Rabi is the eighth largest island of Fiji

History

Rabi was the first place in Fiji where Indian indentured labourers were employed. When the first Indians were brought to Fiji abroad the Leonidas in 1879, most European planters refused to employ them because of the extra cost involved. One planter who was sympathetic to Government policies was Captain J. Hill of Rabi Island, and he agreed to take 106 of indentured labourers as field workers.[2]

Prior to the Banaban resettlement on Rabi, the island was owned and used as a copra plantation by the Lever’s Pacific Plantations Pty Ltd. At the beginning of World War II, the British government purchased the island with phosphate royalties from Banaba, in the quest to relocate the Banabans from Banaba.

At the end of World War II, Kiribati's (and Fiji's) British colonial rulers decided to resettle most of Banaba's population on Rabi Island, because of the ongoing devastation of Banaba caused by phosphate mining - or, as some would say, to get them out of the way of the mining. Some have since returned, but the majority have remained on Rabi or elsewhere in Fiji.

The Banabans came to Fiji in three major waves, with the first group of 703, including 318 children, arriving on the BPC vessel, Triona, on 15 December 1945. Accompanying them were 300 other I-Kiribati. The Banabans had been collected from Japanese internment camps on various islands; they were not given the option of returning to Banaba, on the grounds that the Japanese had destroyed their houses - this was not true. They were told that there were houses waiting for them on Rabi: in fact they were given tents to live in and food rations which lasted for only two months. It was the middle of the hurricane season, and they were still weak from years of Japanese imprisonment: 40 of the oldest Banabans died.[3] They were joined by a second wave between 1975 and 1977, with a final wave arriving between 1981 and 1983, following the ending of phosphate mining in 1979. Recognizing the lack of opportunities for Banabans in their homeland, the Rabi Council assisted the remaining population to move to Rabi after 1981.

On 15 December 2005, sixty years to the day since the arrival of the first Banabans, more than 500 Rabi Islanders were granted citizenship at a ceremony led by Minister for Home Affairs Josefa Vosanibola and fellow-Cabinet Minister Ratu Naiqama Lalabalavu, who is also the Tui Cakau, or Paramount Chief of Cakaudrove and Tovata, to which Rabi belongs. These islanders, who had not previously been naturalized, came from the second and third waves of migration, which were technically illegal but tolerated by the Fijian government on humanitarian grounds.

A decision was made by the Fijian Cabinet in early 2005 to grant citizenship to the residents of Rabi and Kioa Islands, concluding a decade-long quest by the people of both islands for naturalization, which entitles the islanders to provincial and rural development assistance from the government of Fiji. Vosanibola said that although not all of the Rabi islanders had been granted citizenship until now, their contribution to Fiji was enormous, and the government had decided to waive F$1 million of citizenship application fees.

Politics

In a number of ways, Rabi is a political anomaly. Though part of the Province of Cakaudrove, Rabi has a degree of autonomy, with its own council controlling local affairs, though this council is to be merged with its counterpart from Kioa, according to a Cabinet decision of 15 January 2006. And though citizens of Fiji, the Rabi Islanders still hold Kiribati passports, remain the legal landowners of Banaba, and send one representative to the Kiribati parliament (a second one is elected in Banaba), and the Rabi Council municipally administers their original homeland of Banaba. They are also represented in the Fijian House of Representatives, classified as General Electors (an omnibus category for Fijian citizens who are neither indigenous nor of Indian origin). Rabi Island forms part of the North Eastern General Communal Constituency, one of three reserved for General Electors, and of the Lau Taveuni Rotuma Open Constituency, one of 25 seats elected by universal suffrage.

On 19 December 2005, Teitirake Karoro, the Rabi Island Council's representative to the Parliament of Kiribati, said that the Rabi Council was considering giving the right to re-mine Banaba Island to the government of Fiji. This followed the disappointment of the Rabi Islanders at the refusal of the Kiribati Parliament to grant a portion of the A$786 million trust fund from phosphate proceeds to elderly Rabi islanders. Karoro asserted that Banaba is the property of their descendants who live on Rabi, not of the Kiribati government. "The trust fund also belong to us even though we do not live on Kiribati," he asserted. He condemned the Kiribati government's policy not to pay the islanders. Council Secretary Molly Amon said, however, that the Rabi Council had yet to reach a consensus on the matter of transferring any mining rights to the Fijian government.

On 23 December, Reteta Rimon, Kiribati's High Commissioner to Fiji, clarified that Rabi Islanders were in fact entitled to Kiribati government benefits - but only if they returned to Kiribati. She called for negotiations between the Rabi Council of Leaders and the Kiribati government.

Economy and culture

Gilbertese is the main language of daily communication on Rabi Island. The islanders have held fast to many Banaban customs. Development on Rabi is limited; only two manual telephone lines are in operation, and only a few generators electrify the island.

Notable Rabi Islanders

David Ariu Christopher, who served in the House of Representatives from 2001 to 2006, was the first Rabi Islander to hold national office in Fiji.

External links

- Banaba a semi-official resource on both Banaba and Rabi, including geographical and historical information, as well as news.

- Jane Resture has an informative Banaba site, including Rabi.

References

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||