RNA world

The RNA world refers to the self-replicating ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecules that were precursors to all current life on Earth.[1][2][3] It is generally accepted that current life on Earth descends from an RNA world,[4] although RNA-based life may not have been the first life to exist.[5][6]

RNA stores genetic information like DNA, and catalyzes chemical reactions like an enzyme protein. It may, therefore, have played a major step in the evolution of cellular life.[7] The RNA world would have eventually been replaced by the DNA, RNA and protein world of today, likely through an intermediate stage of ribonucleoprotein enzymes such as the ribosome and ribozymes, since proteins large enough to self-fold and have useful activities would only have come about after RNA was available to catalyze peptide ligation or amino acid polymerization.[8] DNA is thought to have taken over the role of data storage due to its increased stability, while proteins, through a greater variety of monomers (amino acids), replaced RNA's role in specialized biocatalysis.

The RNA world hypothesis is supported by many independent lines of evidence, such as the observations that RNA is central to the translation process and that small RNAs can catalyze all of the chemical group and information transfers required for life.[6][9] The structure of the ribosome has been called the "smoking gun," as it showed that the ribosome is a ribozyme, with a central core of RNA and no amino acid side chains within 18 angstroms of the active site where peptide bond formation is catalyzed.[5] Many of the most critical components of cells (those that evolve the slowest) are composed mostly or entirely of RNA. Also, many critical cofactors (ATP, Acetyl-CoA, NADH, etc.) are either nucleotides or substances clearly related to them. This would mean that the RNA and nucleotide cofactors in modern cells are an evolutionary remnant of an RNA-based enzymatic system that preceded the protein-based one seen in all extant life.

Evidence suggests chemical conditions (including the presence of boron, molybdenum and oxygen) for initially producing RNA molecules may have been better on the planet Mars than those on the planet Earth.[2][3] If so, life-suitable molecules, originating on Mars, may have later migrated to Earth via panspermia or similar process.[2][3]

History

One of the challenges in studying abiogenesis is that the system of reproduction and metabolism utilized by all extant life involves three distinct types of interdependent macromolecules (DNA, RNA, and protein). This suggests that life could not have arisen in its current form, and mechanisms have then been sought whereby the current system might have arisen from a simpler precursor system. The concept of RNA as a primordial molecule[8] can be found in papers by Francis Crick[10] and Leslie Orgel,[11] as well as in Carl Woese's 1967 book The Genetic Code.[12] In 1962 the molecular biologist Alexander Rich, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had posited much the same idea in an article he contributed to a volume issued in honor of Nobel-laureate physiologist Albert Szent-Györgyi.[13] Hans Kuhn in 1972 laid out a possible process by which the modern genetic system might have arisen from a nucleotide-based precursor, and this led Harold White in 1976 to observe that many of the cofactors essential for enzymatic function are either nucleotides or could have been derived from nucleotides. He proposed that these nucleotide cofactors represent "fossils of nucleic acid enzymes".[14] The phrase "RNA World" was first used by Nobel laureate Walter Gilbert in 1986, in a commentary on how recent observations of the catalytic properties of various forms of RNA fit with this hypothesis.[15]

Properties of RNA

The properties of RNA make the idea of the RNA world hypothesis conceptually plausible, though its general acceptance as an explanation for the origin of life requires further evidence.[13] RNA is known to form efficient catalysts and its similarity to DNA makes its ability to store information clear. Opinions differ, however, as to whether RNA constituted the first autonomous self-replicating system or was a derivative of a still-earlier system.[8] One version of the hypothesis is that a different type of nucleic acid, termed pre-RNA, was the first one to emerge as a self-reproducing molecule, to be replaced by RNA only later. On the other hand, the recent finding that activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides can be synthesized under plausible prebiotic conditions[16] means that it is premature to dismiss the RNA-first scenarios.[8] Suggestions for 'simple' pre-RNA nucleic acids have included Peptide nucleic acid (PNA), Threose nucleic acid (TNA) or Glycol nucleic acid (GNA).[17][18] Despite their structural simplicity and possession of properties comparable with RNA, the chemically plausible generation of "simpler" nucleic acids under prebiotic conditions has yet to be demonstrated.[19]

RNA as an enzyme

RNA enzymes, or ribozymes, are found in today's DNA-based life and could be examples of living fossils. Ribozymes play vital roles, such as those in the ribosome, which is vital for protein synthesis. Many other ribozyme functions exist; for example, the hammerhead ribozyme performs self-cleavage[20] and an RNA polymerase ribozyme can synthesize a short RNA strand from a primed RNA template.[21]

Among the enzymatic properties important for the beginning of life are:

- The ability to self-replicate, or synthesize other RNA molecules; relatively short RNA molecules that can synthesize others have been artificially produced in the lab. The shortest was 165-bases long, though it has been estimated that only part of the molecule was crucial for this function. One version, 189-bases long, had an error rate of just 1.1% per nucleotide when synthesizing an 11 nucleotide long RNA strand from primed template strands.[22] This 189 base pair ribozyme could polymerize a template of at most 14 nucleotides in length, which is too short for self replication, but a potential lead for further investigation. The longest primer extension performed by a ribozyme polymerase was 20 bases.[23]

- The ability to catalyze simple chemical reactions—which would enhance creation of molecules that are building blocks of RNA molecules (i.e., a strand of RNA which would make creating more strands of RNA easier). Relatively short RNA molecules with such abilities have been artificially formed in the lab.[24][25]

- The ability to conjugate an amino acid to the 3'-end of an RNA in order to use its chemical groups or provide a long-branched aliphatic side-chain.[26]

- The ability to catalyse the formation of peptide bonds to produce short peptides or longer proteins. This is done in modern cells by ribosomes, a complex of several RNA molecules known as rRNA together with many proteins. The rRNA molecules are thought responsible for its enzymatic activity, as no amino acid molecules lie within 18Å of the enzyme's active site.[13] A much shorter RNA molecule has been synthesized in the laboratory with the ability to form peptide bonds, and it has been suggested that rRNA has evolved from a similar molecule.[27] It has also been suggested that amino acids may have initially been involved with RNA molecules as cofactors enhancing or diversifying their enzymatic capabilities, before evolving to more complex peptides. Similarly, tRNA is suggested to have evolved from RNA molecules that began to catalyze amino acid transfer.[28]

RNA in information storage

RNA is a very similar molecule to DNA, and only has two chemical differences. The overall structure of RNA and DNA are immensely similar—one strand of DNA and one of RNA can bind to form a double helical structure. This makes the storage of information in RNA possible in a very similar way to the storage of information in DNA. However RNA is less stable.

Comparison of DNA and RNA structure

The major difference between RNA and DNA is the presence of a hydroxyl group at the 2'-position of the ribose sugar in RNA (illustration, right).[13] This group makes the molecule less stable because when not constrained in a double helix, the 2' hydroxyl can chemically attack the adjacent phosphodiester bond to cleave the phosphodiester backbone. The hydroxyl group also forces the ribose into the C3'-endo sugar conformation unlike the C2'-endo conformation of the deoxyribose sugar in DNA. This forces an RNA double helix to change from a B-DNA structure to one more closely resembling A-DNA.

RNA also uses a different set of bases than DNA—adenine, guanine, cytosine and uracil, instead of adenine, guanine, cytosine and thymine. Chemically, uracil is similar to thymine, differing only by a methyl group, and its production requires less energy.[29] In terms of base pairing, this has no effect. Adenine readily binds uracil or thymine. Uracil is, however, one product of damage to cytosine that makes RNA particularly susceptible to mutations that can replace a GC base pair with a GU (wobble) or AU base pair.

RNA is thought to have preceded DNA, because of their ordering in the biosynthetic pathways. The deoxyribonucleotides used to make DNA are made from ribonucleotides, the building blocks of RNA, by removing the 2'-hydroxyl group. As a consequence a cell must have the ability to make RNA before it can make DNA.

Limitations of information storage in RNA

The chemical properties of RNA make large RNA molecules inherently fragile, and they can easily be broken down into their constituent nucleotides through hydrolysis.[30][31] These limitations do not make use of RNA as an information storage system impossible, simply energy intensive (to repair or replace damaged RNA molecules) and prone to mutation. While this makes it unsuitable for current 'DNA optimised' life, it may have been acceptable for more primitive life.

RNA as a regulator

Riboswitches have been found to act as regulators of gene expression, particularly in bacteria, but also in plants and archaea. Riboswitches alter their secondary structure in response to the binding of a metabolite. This change in structure can result in the formation or disruption of a terminator, truncating or permitting transcription respectively.[32] Alternatively, riboswitches may bind or occlude the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, affecting translation.[33] It has been suggested that these originated in an RNA-based world.[34] In addition, RNA thermometers regulate gene expression in response to temperature changes.[35]

Support and difficulties

The RNA world hypothesis is supported by RNA's ability to store, transmit, and duplicate genetic information, as DNA does. RNA can act as a ribozyme, a special type of enzyme. Because it can perform the tasks of both DNA and enzymes, RNA is believed to have once been capable of supporting independent life forms.[13] Some viruses use RNA as their genetic material, rather than DNA.[36] Further, while nucleotides were not found in Miller-Urey's origins of life experiments, their formation in prebiotically plausible conditions has now been reported, as noted above;[16] the purine base known as adenine is merely a pentamer of hydrogen cyanide. Experiments with basic ribozymes, like Bacteriophage Qβ RNA, have shown that simple self-replicating RNA structures can withstand even strong selective pressures (e.g., opposite-chirality chain terminators).[37]

Since there were no known chemical pathways for the abiogenic synthesis of nucleotides from pyrimidine nucleobases cytosine and uracil under prebiotic conditions, it is thought by some that nucleic acids did not contain these nucleobases seen in life's nucleic acids.[38] The nucleoside cytosine has a half-life in isolation of 19 days at 100 °C (212 °F) and 17,000 years in freezing water, which some argue is too short on the geologic time scale for accumulation.[39] Others have questioned whether ribose and other backbone sugars could be stable enough to find in the original genetic material,[40] and have raised the issue that all ribose molecules would have had to be the same enantiomer, as any nucleotide of the wrong chirality acts as a chain terminator.[41]

Pyrimidine ribonucleosides and their respective nucleotides have been prebiotically synthesised by a sequence of reactions that by-pass free sugars and assemble in a stepwise fashion by going against the dogma that nitrogenous and oxygenous chemistries should be avoided. In a series of publications, The Sutherland Group at the School of Chemistry, University of Manchester have demonstrated high yielding routes to cytidine and uridine ribonucleotides built from small 2 and 3 carbon fragments such as glycolaldehyde, glyceraldehyde or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, cyanamide and cyanoacetylene. One of the steps in this sequence allows the isolation of enantiopure ribose aminooxazoline if the enantiomeric excess of glyceraldehyde is 60% or greater, of possible interest towards biological homochirality.[42] This can be viewed as a prebiotic purification step, where the said compound spontaneously crystallised out from a mixture of the other pentose aminooxazolines. Aminooxazolines can react with cyanoacetylene in a mild and highly efficient manner, controlled by inorganic phosphate, to give the cytidine ribonucleotides. Photoanomerization with UV light allows for inversion about the 1' anomeric centre to give the correct beta stereochemistry, one problem with this chemistry is the selective phosphorylation of alpha-cytidine at the 2' position.[43] However, in 2009 they showed that the same simple building blocks allow access, via phosphate controlled nucleobase elaboration, to 2',3'-cyclic pyrimidine nucleotides directly, which are known to be able to polymerise into RNA.[44] This was hailed as strong evidence for the RNA world.[45] The paper also highlighted the possibility for the photo-sanitization of the pyrimidine-2',3'-cyclic phosphates.[44] A potential weakness of these routes is the generation of enantioenriched glyceraldehyde, or its 3-phosphate derivative (glyceraldehyde prefers to exist as its keto tautomer dihydroxyacetone).

On August 8, 2011, a report, based on NASA studies with meteorites found on Earth, was published suggesting building blocks of RNA (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules) may have been formed extraterrestrially in outer space.[46][47][48] On August 29, 2012, and in a world first, astronomers at Copenhagen University reported the detection of a specific sugar molecule, glycolaldehyde, in a distant star system. The molecule was found around the protostellar binary IRAS 16293-2422, which is located 400 light years from Earth.[49][50] Glycolaldehyde is needed to form ribonucleic acid, or RNA, which is similar in function to DNA. This finding suggests that complex organic molecules may form in stellar systems prior to the formation of planets, eventually arriving on young planets early in their formation.[51]

"Molecular biologist's dream"

"Molecular biologist's dream" is a phrase coined by Gerald Joyce and Leslie Orgel to refer to the problem of emergence of self-replicating RNA molecules, as any movement towards an RNA world on a properly modeled prebiotic early Earth would have been continuously suppressed by destructive reactions.[52] It was noted that many of the steps needed for the nucleotides formation do not proceed efficiently in prebiotic conditions.[53] Joyce and Orgel specifically referred the molecular biologist's dream to "a magic catalyst" that could "convert the activated nucleotides to a random ensemble of polynucleotide sequences, a subset of which had the ability to replicate".[52]

Joyce and Orgel further argued that nucleotides cannot link unless there is some activation of the phosphate group, whereas the only effective activating groups for this are "totally implausible in any prebiotic scenario", particularly adenosine triphosphate.[52] According to Joyce and Orgel, in case of the phosphate group activation, the basic polymer product would have 5',5'-pyrophosphate linkages, while the 3',5'-phosphodiester linkages, which are present in all known RNA, would be much less abundant.[52] The associated molecules would have been also prone to addition of incorrect nucleotides or to reactions with numerous other substances likely to have been present.[52] The RNA molecules would have been also continuously degraded by such destructive process as spontaneous hydrolysis, present on the early Earth.[52] Joyce and Orgel proposed to reject "the myth of a self-replicating RNA molecule that arose de novo from a soup of random polynucleotides"[52] and hypothesised about a scenario where the prebiotic processes furnish pools of enantiopure beta-D-ribonucleosides.[54]

Prebiotic RNA synthesis

Nucleotides are the fundamental molecules that combine in series to form RNA. They consist of a nitrogenous base attached to a sugar-phosphate backbone. RNA is made of long stretches of specific nucleotides arranged so that their sequence of bases carries information. The RNA world hypothesis holds that in the primordial soup (or sandwich), there existed free-floating nucleotides. These nucleotides regularly formed bonds with one another, which often broke because the change in energy was so low. However, certain sequences of base pairs have catalytic properties that lower the energy of their chain being created, enabling them to stay together for longer periods of time. As each chain grew longer, it attracted more matching nucleotides faster, causing chains to now form faster than they were breaking down.

These chains have been proposed by some as the first, primitive forms of life.[55] In an RNA world, different sets of RNA strands would have had different replication outputs, which would have increased or decreased their frequency in the population, i.e. natural selection. As the fittest sets of RNA molecules expanded their numbers, novel catalytic properties added by mutation, which benefitted their persistence and expansion, could accumulate in the population. Such an autocatalytic set of ribozymes, capable of self replication in about an hour, has been identified. It was produced by molecular competition (in vitro evolution) of candidate enzyme mixtures.[56]

Competition between RNA may have favored the emergence of cooperation between different RNA chains, opening the way for the formation of the first protocell. Eventually, RNA chains developed with catalytic properties that help amino acids bind together (a process called peptide-bonding). These amino acids could then assist with RNA synthesis, giving those RNA chains that could serve as ribozymes the selective advantage. The ability to catalyze one step in protein synthesis, aminoacylation of RNA, has been demonstrated in a short (five-nucleotide) segment of RNA.[57]

One of the problems with the RNA world hypothesis is to discover the pathway by which RNA became upgraded to the DNA system. Ken Stedman of Portland State University in Oregon, may have found the solution. While filtering virus-sized particles from a hot acidic lake in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California, he discovered 400,000 pieces of viral DNA. Some of these, however, contained a protein coat of reverse transcriptase enzyme normally associated with RNA based retroviruses. This lack of respect for biochemical boundaries virologists like Luis Villareal of the University of California Irvine believe would have been a characteristic of a pre RNA virus world up to 4 billion years ago.[58][59] This finding bolsters the argument for the transfer of information from the RNA world to the emerging DNA world before the emergence of the Last Universal Common Ancestor. From the research, the diversity of this virus world is still with us.

In March 2015, NASA scientists reported that, for the first time, complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine and thymine, have been formed in the laboratory under conditions found only in outer space, using starting chemicals, like pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the Universe, may have been formed in giant red stars or in interstellar dust and gas clouds, according to the scientists.[60]

Viroids

Additional evidence supporting the concept of an RNA world has resulted from research on viroids, the first representatives of a novel domain of "subviral pathogens."[61][62] Viroids are mostly plant pathogens, which consist of short stretches (a few hundred nucleobases) of highly complementary, circular, single-stranded, and non-coding RNA without a protein coat. Compared with other infectious plant pathogens, viroids are extremely small in size, ranging from 246 to 467 nucleobases. In comparison, the genome of the smallest known viruses capable of causing an infection are about 2,000 nucleobases long.[63]

In 1989, Diener proposed that, based on their characteristic properties, viroids are more plausible "living relics" of the RNA world than are introns or other RNAs then so considered.[64] If so, viroids have attained potential significance beyond plant pathology to evolutionary biology, by representing the most plausible macromolecules known capable of explaining crucial intermediate steps in the evolution of life from inanimate matter (see: abiogenesis).

Apparently, Diener's hypothesis lay dormant until 2014, when Flores et al. published a review paper, in which Diener's evidence supporting his hypothesis was summarized.[65] In the same year, a New York Times science writer published a popularized version of Diener's proposal, in which, however, he mistakenly credited Flores et al. with the hypothesis' original conception.[66]

Pertinent viroid properties listed in 1989 are: 1. their small size, imposed by error-prone replication; 2. their high guanine and cytosine content, which increases stability and replication fidelity; 3. their circular structure, which assures complete replication without genomic tags; 4. existence of structural periodicity, which permits modular assembly into enlarged genomes; 5. their lack of protein-coding ability, consistent with a ribosome-free habitat; and 6. replication mediated in some by ribozymes—the fingerprint of the RNA world.[65]

The existence, in extant cells, of RNAs with molecular properties predicted for RNAs of the RNA World constitutes an additional argument supporting the RNA World hypothesis.

Origin of sex

Eigen et al.[67] and Woese[68] proposed that the genomes of early protocells were composed of single-stranded RNA, and that individual genes corresponded to separate RNA segments, rather than being linked end-to-end as in present day DNA genomes. A protocell that was haploid (one copy of each RNA gene) would be vulnerable to damage, since a single lesion in any RNA segment would be potentially lethal to the protocell (e.g. by blocking replication or inhibiting the function of an essential gene).

Vulnerability to damage could be reduced by maintaining two or more copies of each RNA segment in each protocell, i.e. by maintaining diploidy or polyploidy. Genome redundancy would allow a damaged RNA segment to be replaced by an additional replication of its homolog. However for such a simple organism, the proportion of available resources tied up in the genetic material would be a large fraction of the total resource budget. Under limited resource conditions, the protocell reproductive rate would likely be inversely related to ploidy number. The protocell's fitness would be reduced by the costs of redundancy. Consequently, coping with damaged RNA genes while minimizing the costs of redundancy would likely have been a fundamental problem for early protocells.

A cost-benefit analysis was carried out in which the costs of maintaining redundancy were balanced against the costs of genome damage.[69] This analysis led to the conclusion that, under a wide range of circumstances, the selected strategy would be for each protocell to be haploid, but to periodically fuse with another haploid protocell to form a transient diploid. The retention of the haploid state maximizes the growth rate. The periodic fusions permit mutual reactivation of otherwise lethally damaged protocells. If at least one damage-free copy of each RNA gene is present in the transient diploid, viable progeny can be formed. For two, rather than one, viable daughter cells to be produced would require an extra replication of the intact RNA gene homologous to any RNA gene that had been damaged prior to the division of the fused protocell. The cycle of haploid reproduction, with occasional fusion to a transient diploid state, followed by splitting to the haploid state, can be considered to be the sexual cycle in its most primitive form.[69][70] In the absence of this sexual cycle, haploid protocells with a damage in an essential RNA gene would simply die.

This model for the early sexual cycle is hypothetical, but it is very similar to the known sexual behavior of the segmented RNA viruses, which are among the simplest organisms known. Influenza virus, whose genome consists of 8 physically separated single-stranded RNA segments,[71] is an example of this type of virus. In segmented RNA viruses, “mating” can occur when a host cell is infected by at least two virus particles. If these viruses each contain an RNA segment with a lethal damage, multiple infection can lead to reactivation providing that at least one undamaged copy of each virus gene is present in the infected cell. This phenomenon is known as “multiplicity reactivation”. Multiplicity reactivation has been reported to occur in influenza virus infections after induction of RNA damage by UV-irradiation,[72] and ionizing radiation.[73]

Further developments

Patrick Forterre has been working on a novel hypothesis, called "three viruses, three domains":[74] that viruses were instrumental in the transition from RNA to DNA and the evolution of Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota. He believes the last common ancestor (specifically, the "last universal cellular ancestor")[74] was RNA-based and evolved RNA viruses. Some of the viruses evolved into DNA viruses to protect their genes from attack. Through the process of viral infection into hosts the three domains of life evolved.[74][75] Another interesting proposal is the idea that RNA synthesis might have been driven by temperature gradients, in the process of thermosynthesis.[76] Single nucleotides have been shown to catalyze organic reactions.[77]

Alternative hypotheses

The hypothesized existence of an RNA world does not exclude a "Pre-RNA world", where a metabolic system based on a different nucleic acid is proposed to pre-date RNA. A candidate nucleic acid is peptide nucleic acid (PNA), which uses simple peptide bonds to link nucleobases.[78] PNA is more stable than RNA, but its ability to be generated under prebiological conditions has yet to be demonstrated experimentally.

Threose nucleic acid (TNA) has also been proposed as a starting point, as has glycol nucleic acid (GNA), and like PNA, also lack experimental evidence for their respective abiogenesis.

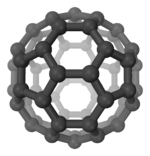

An alternative—or complementary— theory of RNA origin is proposed in the PAH world hypothesis, whereby polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) mediate the synthesis of RNA molecules.[79] PAHs are the most common and abundant of the known polyatomic molecules in the visible Universe, and are a likely constituent of the primordial sea.[80] PAHs, along with fullerenes (also implicated in the origin of life),[81] have been recently detected in nebulae.[82]

The iron-sulfur world theory proposes that simple metabolic processes developed before genetic materials did, and these energy-producing cycles catalyzed the production of genes.

Some of the difficulties over producing the precursors on earth are bypassed by another alternative or complementary theory for their origin, panspermia. It discusses the possibility that the earliest life on this planet was carried here from somewhere else in the galaxy, possibly on meteorites similar to the Murchison meteorite.[83] This does not invalidate the concept of an RNA world, but posits that this world or its precursors originated not on Earth but rather another, probably older, planet.

There are hypotheses that are in direct conflict to the RNA world hypothesis. The relative chemical complexity of the nucleotide and the unlikelihood of it spontaneously arising, along with the limited number of combinations possible among four base forms as well as the need for RNA polymers of some length before seeing enzymatic activity have led some to reject the RNA world hypothesis in favor of a metabolism-first hypothesis, where the chemistry underlying cellular function arose first, and the ability to replicate and facilitate this metabolism. Another proposal is that the dual molecule system we see today, where a nucleotide-based molecule is needed to synthesize protein, and a protein-based molecule is needed to make nucleic acid polymers, represents the original form of life.[84] This theory is called the Peptide-RNA world, and offers a possible explanation for the rapid evolution of high-quality replication in RNA (since proteins are catalysts), with the disadvantage of having to postulate the formation of two complex molecules, an enzyme (from peptides) and a RNA (from nucleotides). In this Peptide-RNA World scenario, RNA would have contained the instructions for life while peptides (simple protein enzymes) would have accelerated key chemical reactions to carry out those instructions.[85] The study leaves open the question of exactly how those primitive systems managed to replicate themselves — something neither the RNA World hypothesis nor the Peptide-RNA World theory can yet explain, unless polymerases —enzymes that rapidly assemble the RNA molecule— played a role.[85]

Implications of the RNA world

The RNA world hypothesis, if true, has important implications for the definition of life. For most of the time that followed Watson and Crick's elucidation of DNA structure in 1953, life was largely defined in terms of DNA and proteins: DNA and proteins seemed the dominant macromolecules in the living cell, with RNA only aiding in creating proteins from the DNA blueprint.

The RNA world hypothesis places RNA at center-stage when life originated. This has been accompanied by many studies in the last ten years that demonstrate important aspects of RNA function not previously known—and supports the idea of a critical role for RNA in the mechanisms of life. The RNA world hypothesis is supported by the observations that ribosomes are ribozymes: the catalytic site is composed of RNA, and proteins hold no major structural role and are of peripheral functional importance. This was confirmed with the deciphering of the 3-dimensional structure of the ribosome in 2001. Specifically, peptide bond formation, the reaction that binds amino acids together into proteins, is now known to be catalyzed by an adenine residue in the rRNA.

Other interesting discoveries demonstrate a role for RNA beyond a simple message or transfer molecule.[86] These include the importance of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) in the processing of pre-mRNA and RNA editing, RNA interference (RNAi), and reverse transcription from RNA in eukaryotes in the maintenance of telomeres in the telomerase reaction.[87]

See also

References

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (September 25, 2014). "A Tiny Emissary From the Ancient Past". New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Zimmer, Carl (September 12, 2013). "A Far-Flung Possibility for the Origin of Life". New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Webb, Richard (August 29, 2013). "Primordial broth of life was a dry Martian cup-a-soup". New Scientist. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ↑

- Copley SD, Smith E, Morowitz HJ (2007). "The origin of the RNA world: co-evolution of genes and metabolism.". Bioorg Chem 35 (6): 430–43. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.08.001. PMID 17897696. "The proposal that life on Earth arose from an RNA World is widely accepted."

- Orgel LE (2003). "Some consequences of the RNA world hypothesis.". Orig Life Evol Biosph 33 (2): 211–8. PMID 12967268. "It now seems very likely that our familiar DNA/RNA/protein world was preceded by an RNA world"

- Robertson MP, Joyce GF (2012). "The origins of the RNA world.". Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4 (5). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003608. PMC 3331698. PMID 20739415. "There is now strong evidence indicating that an RNA World did indeed exist before DNA- and protein-based life."

- Neveu M, Kim HJ, Benner SA (2013). "The "strong" RNA world hypothesis: fifty years old.". Astrobiology 13 (4): 391–403. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0868. PMID 23551238."[The RNA world's existence] has broad support within the community today."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Robertson MP, Joyce GF (2012). "The origins of the RNA world.". Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4 (5). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003608. PMC 3331698. PMID 20739415.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cech TR (2012). "The RNA worlds in context.". Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4 (7): a006742. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006742. PMC 3385955. PMID 21441585.

- ↑ This does not necessarily mean that the first life was RNA-based. For example, Thomas Čech proposes that multiple self-replicating molecular systems preceded RNA.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Cech, T.R. (2011). The RNA Worlds in Context. Source: Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309-0215. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011 Feb 16. pii: cshperspect.a006742v1. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006742. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ Yarus M (2011). "Getting past the RNA world: the initial Darwinian ancestor.". Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3 (4). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003590. PMC 3062219. PMID 20719875.

- ↑ Crick FH (1968). "The origin of the genetic code". J Mol Biol 38 (3): 367–379. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6. PMID 4887876.

- ↑ Orgel LE (1968). "Evolution of the genetic apparatus". J Mol Biol 38 (3): 381–393. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(68)90393-8. PMID 5718557.

- ↑ Woese C.R. (1967). The genetic code: The molecular basis for genetic expression. p. 186. Harper & Row

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Atkins, John F.; Gesteland, Raymond F.; Cech, Thomas (2006). The RNA world: the nature of modern RNA suggests a prebiotic RNA world. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-739-3.

- ↑ White, HB III (1976). "Coenzymes as Fossils of an Earlier Metabolic State". J Mol Evol 7 (2): 101–104. doi:10.1007/BF01732468. PMID 1263263.

- ↑ Gilbert, Walter (February 1986). "The RNA World". Nature 319 (6055): 618. Bibcode:1986Natur.319..618G. doi:10.1038/319618a0.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Powner M.W., Gerland B, Sutherland J.D. (2009). "Synthesis of activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides in prebiotically plausible conditions". Nature 459 (7244): 239–242. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..239P. doi:10.1038/nature08013. PMID 19444213.

- ↑ Orgel, Leslie (November 2000). "A Simpler Nucleic Acid". Science 290 (5495): 1306–7. doi:10.1126/science.290.5495.1306. PMID 11185405.

- ↑ Nelson, K.E.; Levy, M.; Miller, S.L. (April 2000). "Peptide nucleic acids rather than RNA may have been the first genetic molecule". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 (8): 3868–71. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.3868N. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.8.3868. PMC 18108. PMID 10760258.

- ↑ Sutherland, J.D; Anastasi, C., Buchet F.F, Crower M.A, Parkes A.L, Powner M. W., Smith J.M. (April 2007). "RNA: Prebiotic Product, or Biotic Invention". Chemistry & Biodiversity 4 (4): 721–739. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790060. PMID 17443885.

- ↑ Forster AC, Symons RH (1987). "Self-cleavage of plus and minus RNAs of a virusoid and a structural model for the active sites". Cell 49 (2): 211–220. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90562-9. PMID 2436805.

- ↑ Johnston W, Unrau P, Lawrence M, Glasner M, Bartel D (2001). "RNA-catalyzed RNA polymerization: accurate and general RNA-templated primer extension" (PDF). Science 292 (5520): 1319–25. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1319J. doi:10.1126/science.1060786. PMID 11358999.

- ↑ Johnston, W. K.; Unrau, P. J.; Lawrence, M. S.; Glasner, M. E.; Bartel, D. P. (2001). "RNA-Catalyzed RNA Polymerization: Accurate and General RNA-Templated Primer Extension". Science 292 (5520): 1319–25. doi:10.1126/science.1060786. PMID 11358999.

- ↑ Hani S. Zaher and Peter J. Unrau, Selection of an improved RNA polymerase ribozyme with superior extension and fidelity. RNA (2007), 13:1017-1026

- ↑ Huang, Yang, and Yarus, RNA enzymes with two small-molecule substrates. Chemistry & Biology, Vol 5, 669-678, November 1998

- ↑ Unrau, P. J.; Bartel, D. P. (1998). "RNA-catalysed nucleotide synthesis". Nature 395 (6699): 260–263. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..260U. doi:10.1038/26193. PMID 9751052.

- ↑ Erives A (2011). "A Model of Proto-Anti-Codon RNA Enzymes Requiring L-Amino Acid Homochirality". J Molecular Evolution 73 (1–2): 10–22. doi:10.1007/s00239-011-9453-4. PMC 3223571. PMID 21779963.

- ↑ Zhang, Biliang; Cech, Thomas R. (1997). "Peptide bond formation by in vitro selected ribozymes". Nature 390 (6655): 96–100. Bibcode:1997Natur.390...96Z. doi:10.1038/36375. PMID 9363898.

- ↑ Szathmary, E. (1999). "The origin of the genetic code: amino acids as cofactors in an RNA world". Trends in Genetics 15 (6): 223–229. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01730-8. PMID 10354582.

- ↑ http://www.humpath.com/uracil

- ↑ Lindahl, T (April 1993). "Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA". Nature 362 (6422): 709–15. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..709L. doi:10.1038/362709a0. PMID 8469282.

- ↑ Pääbo, S (November 1993). "Ancient DNA". Scientific American 269 (5): 60–66. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1193-86.

- ↑ Nudler E, Mironov AS (2004). "The riboswitch control of bacterial metabolism". Trends Biochem Sci 29 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.004. PMID 14729327.

- ↑ Tucker BJ, Breaker RR (2005). "Riboswitches as versatile gene control elements". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 15 (3): 342–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.003. PMID 15919195.

- ↑ Switching the light on plant riboswitches. Samuel Bocobza and Asaph Aharoni Trends in Plant Science Volume 13, Issue 10, October 2008, Pages 526-533 doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.07.004 PMID 18778966

- ↑ Narberhaus F, Waldminghaus T, Chowdhury S (January 2006). "RNA thermometers". FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2005.004.x. PMID 16438677. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Patton, John T. Editor (2008). Segmented Double-stranded RNA Viruses: Structure and Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. Editor's affiliation: Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892-8026. ISBN 978-1-904455-21-9

- ↑ Bell, Graham: The Basics of Selection. Springer, 1997.

- ↑ Orgel, L. (1994). "The origin of life on earth". Scientific American 271 (4): 81. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1094-76. PMID 7524147.

- ↑ Levy, Matthew; Miller, Stanley L. (1998). "The stability of the RNA bases: Implications for the origin of life". PNAS 95 (14): 7933–7938. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.7933L. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.7933. PMC 20907. PMID 9653118.

- ↑ Larralde, R.; Robertson, M. P.; Miller, S. L. (1995). "Rates of decomposition of ribose and other sugars: implications for chemical evolution". PNAS 92 (18): 8158–8160. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.8158L. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.18.8158. PMC 41115. PMID 7667262.

- ↑ Joyce GF et al. (1984). "Chiral selection in poly(C)-directed synthesis of oligo(G)". Nature 310 (5978): 602–604. Bibcode:1984Natur.310..602J. doi:10.1038/310602a0. PMID 6462250.

- ↑ Direct Assembly of Nucleoside Precursors from Two- and Three-Carbon Units Carole Anastasi, Michael A. Crowe, Matthew W. Powner, John D. Sutherland Angewandte Chemie International Edition Volume 45, Issue 37 , Pages 6176–79

- ↑ Potentially Prebiotic Synthesis of Pyrimidine β-D-Ribonucleotides by Photoanomerization/Hydrolysis of α-D-Cytidine-2′-Phosphate Matthew W. Powner, John D. Sutherland ChemBioChem Volume 9, Issue 15 , Pages 2386–87

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Powner MW, Gerland B, Sutherland JD (2009). "Synthesis of activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides in prebiotically plausible conditions". Nature 459 (7244): 239–242. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..239P. doi:10.1038/nature08013. PMID 19444213.

- ↑ Van Noorden R (2009). "RNA world easier to make". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2009.471.

- ↑ Callahan, M.P.; Smith, K.E.; Cleaves, H.J.; Ruzicka, J.; Stern, J.C.; Glavin, D.P.; House, C.H.; Dworkin, J.P. (11 August 2011). "Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 108 (34): 13995–8. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813995C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106493108. PMC 3161613. PMID 21836052. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ Steigerwald, John (8 August 2011). "NASA Researchers: DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space". NASA. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- ↑ ScienceDaily Staff (9 August 2011). "DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space, NASA Evidence Suggests". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- ↑ Than, Ker (August 29, 2012). "Sugar Found In Space". National Geographic. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ↑ Staff (August 29, 2012). "Sweet! Astronomers spot sugar molecule near star". AP News. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ↑ Jørgensen, J. K.; Favre, C.; Bisschop, S.; Bourke, T.; Dishoeck, E.; Schmalzl, M. (2012). "Detection of the simplest sugar, glycolaldehyde, in a solar-type protostar with ALMA" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal Letters. eprint 757: L4. Bibcode:2012ApJ...757L...4J. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/757/1/L4.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 52.6 Gordon C. Mills, Dean Kenyon. "The RNA World: A Critique". Access Research Network. Retrieved 10 Sep 2011.

- ↑ Schopf, J. William (2002). Life's origin: the beginnings of biological evolution. University of California Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-520-23390-5.

- ↑ "Prebiotic RNA chemistry: realising the molecular biologist's dream". Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. Retrieved 10 Sep 2011.

- ↑ Villarreal LP, Witzany G (2013). The DNA Habitat and its RNA Inhabitants: At the Dawn of RNA Sociology 6: 1-12. doi:10.4137/GEI.S11490

- ↑ Lincoln, Tracey A.; Joyce, Gerald F. (January 8, 2009). "Self-Sustained Replication of an RNA Enzyme". Science (New York: American Association for the Advancement of Science) 323 (5918): 1229–32. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1229L. doi:10.1126/science.1167856. PMC 2652413. PMID 19131595. Retrieved 2009-01-13. Lay summary – Medical News Today (January 12, 2009).

- ↑ Rebecca M. Turk, Nataliya V. Chumachenko, and Michael Yarus (February 22, 2010). "Multiple translational products from a five-nucleotide ribozyme". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (10): 4585–89. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.4585T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912895107. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 2826339. PMID 20176971. Lay summary – ScienceDaily (February 24, 2010).

- ↑ Holmes, Bob (2012) "First Glimpse at the birth of DNA" (New Scientist April 12, 2012)

- ↑ Diemer, Geoffrey; Stedman, Kenneth (19 April 2012). "A novel virus genome discovered in an extreme environment suggests recombination between unrelated groups of RNA and DNA viruses". Biology Direct (BioMed Central) 7 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-7-13. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ Marlaire, Ruth (3 March 2015). "NASA Ames Reproduces the Building Blocks of Life in Laboratory". NASA. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ ref name="pmid5095900">Diener TO (August 1971). "Potato spindle tuber "virus". IV. A replicating, low molecular weight RNA". Virology 45 (2): 411–28. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(71)90342-4. PMID 5095900.

- ↑ "ARS Research Timeline – Tracking the Elusive Viroid". 2006-03-02. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Sänger first1=HL; Klotz, G; Riesner, D; Gross, HJ; Kleinschmidt, AK (1979). "viroids are single-stranded, covalently closed, circular RNA molecules, existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures". Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 73 (11): 3852–56.

- ↑ Diener, T.O.(1989). "Circular RNAs: Relics of precellular evolution?" Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 86 (23): 9370–9374. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.9370D. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.23.9370. PMC 298497. PMID 2480600. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Flores, R., Gago-Zachert, S., Serra, P., Sanjuan, R., Elena, S.F. "Viroids: Survivors from the RNA World?" Ann.Rev.Microbiol. 68: 395–41, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2014

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (September 25, 2014). "A Tiny Emissary From the Ancient Past. url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/25/science/a-tiny-emissary-from-the-ancient-past.html?partner=rss&emc=rss". New York Times.

- ↑ Eigen M, Gardiner W, Schuster P, Winkler-Oswatitsch R (April 1981). "The origin of genetic information". Sci. Am. 244 (4): 88–92, 96, et passim. Bibcode:1981SciAm.244...88H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0481-88. PMID 6164094.

- ↑ Woese CR (1983). The primary lines of descent and the universal ancestor. Chapter in Bendall, D. S. (1983). Evolution from molecules to men. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28933-5. pp. 209-233.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (October 1984). "Origin of sex". J. Theor. Biol. 110 (3): 323–51. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80178-2. PMID 6209512.

- ↑ Bernstein, Carol; Bernstein, Harris (1991). Aging, sex, and DNA repair. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-092860-4. see pgs. 293-297

- ↑ Lamb RA, Choppin PW (1983). "The gene structure and replication of influenza virus". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52: 467–506. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.002343. PMID 6351727.

- ↑ BARRY RD (August 1961). "The multiplication of influenza virus. II. Multiplicity reactivation of ultraviolet irradiated virus". Virology 14 (4): 398–405. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(61)90330-0. PMID 13687359.

- ↑ Gilker JC, Pavilanis V, Ghys R (June 1967). "Multiplicity reactivation in gamma irradiated influenza viruses". Nature 214 (5094): 1235–57. Bibcode:1967Natur.214.1235G. doi:10.1038/2141235a0. PMID 6066111.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 Forterre, Patrick. "Three RNA cells for ribosomal lineages and three DNA viruses to replicate their genomes: A hypothesis for the origin of cellular domain"

- ↑ Zimmer C. (2006). "Did DNA come from viruses?". Science 312 (5775): 870–2. doi:10.1126/science.312.5775.870. PMID 16690855.

- ↑ Anthonie W.J. Muller (2005). "Thermosynthesis as energy source for the RNA World: a model for the bioenergetics of the origin of life". Biosystems 82 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.06.003. PMID 16024164.

- ↑ Kumar, Atul; Siddharth Sharma; Ram Awatar Maurya (2010). "Single Nucleotide-Catalyzed Biomimetic Reductive Amination". Advanced Synthesis and Catalyst 352 (13): 2227. doi:10.1002/adsc.201000178.

- ↑ Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freier SM, Driver DA, Berg RH, Kim SK, Nordén B, and Nielsen PE (1993). "PNA Hybridizes to Complementary Oligonucleotides Obeying the Watson-Crick Hydrogen Bonding Rules". Nature 365 (6446): 566–8. Bibcode:1993Natur.365..566E. doi:10.1038/365566a0. PMID 7692304.

- ↑ Platts, Simon Nicholas, "The PAH World - Discotic polynuclear aromatic compounds as a mesophase scaffolding at the origin of life"

- ↑ Allamandola, Louis et Al. "Cosmic Distribution of Chemical Complexity"

- ↑ Atkinson, Nancy (2010-10-27). "Buckyballs Could Be Plentiful in the Universe". Universe Today. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ García-Hernández, D. A.; Manchado, A.; García-Lario, P.; Stanghellini, L.; Villaver, E.; Shaw, R. A.; Szczerba, R.; Perea-Calderón, J. V. (2010-10-28). "Formation Of Fullerenes In H-Containing Planetary Nebulae". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 724: L39. arXiv:1009.4357. Bibcode:2010ApJ...724L..39G. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/724/1/L39.

- ↑ Bernstein MP, Sandford SA, Allamandola LJ, Gillette JS, Clemett SJ, Zare RN (February 1999). "UV irradiation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ices: production of alcohols, quinones, and ethers". Science 283 (5405): 1135–8. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.1135B. doi:10.1126/science.283.5405.1135. PMID 10024233.

- ↑ Kunin V. (October 2000). "A system of two polymerases--a model for the origin of life". Origins of life and evolution of the biosphere 30 (5): 459–466. Bibcode:2000OLEB...30..459K. doi:10.1023/A:1006672126867. PMID 11002892.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Challenging Assumptions About the Origin of Life". Astrobiology Magazine. 18 September 2013. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- ↑ Witzany G (2014) RNA Sociology: Group Behavioral Motifs of RNA Consortia. Life 4:800-818. PMID 25426799

- ↑ Witzany G (2008). The Viral Origins of Telomeres and Telomerases and their Important Role in Eukaryogenesis and Genome Maintenance. Biosemiotics 1: 191-206. doi:10.1007/s12304-008-9018-0

Further reading

- Cairns-Smith, A. G. (1993). Genetic Takeover: And the Mineral Origins of Life. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23312-7.

- Orgel, L. E. (October 1994). "The origin of life on the Earth". Scientific American 271 (4): 76–83. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1094-76. PMID 7524147.

- Orgel, L. E. (2004). "Prebiotic Chemistry and the Origin of the RNA World". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 39 (2): 99–123. doi:10.1080/10409230490460765. ISSN 1549-7798. PMID 15217990.

- Woolfson, Adrian (September 2000). Life Without Genes. London: Flamingo. ISBN 978-0-00-654874-4.

- Vlassov, Alexander V.; Kazakov, Sergei A.; Johnston, Brian H.; Landweber, Laura F. (July 2005). "The RNA World on Ice: A New Scenario for the Emergence of RNA Information". Journal of Molecular Evolution 61 (2): 264–273. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0362-7. PMID 16044244.

- Engelhart, Aaron E.; Hud, Nicholas V. (2011). "Primitive genetic polymers" (PDF). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2 (12): a002196. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a002196. PMC 2982173. PMID 20462999.

- Bernhardt, Harold S. (2012). "The RNA world hypothesis: the worst theory of the early evolution of life (except for all the others)". Biol Direct 7 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-7-23. PMC 3495036. PMID 22793875.

External links

- "The RNA world" (2001) by Sidney Altman, on the Nobel prize website

- "Exploring the new RNA world" (2004) by Thomas R. Cech, on the Nobel prize website

- "The Formation of the RNA World" by James P. Ferris

- "Exploring Life's Origins: a Virtual Exhibit"

- http://www.hhmi.org/bulletin/pdf/june2002/RNA.pdf HHMI bulletin

| ||||||||||