Quarantine

A quarantine is used to separate and restrict the movement of persons; it is a 'state of enforced isolation'.[1] This is often used in connection to disease and illness, such as those who may possibly have been exposed to a communicable disease.[2] The term is often erroneously used to mean medical isolation, which is "to separate ill persons who have a communicable disease from those who are healthy."[3] The word comes from the Italian (seventeenth-century Venetian) quaranta, meaning forty, which is the number of days ships were required to be isolated before passengers and crew could go ashore during the Black Death plague epidemic.[4] Quarantine can be applied to humans, but also to animals of various kinds, and both as part of border control as well as within a country.

In practice

The quarantining of people often raises questions of civil rights, especially in cases of long confinement or segregation from society, such as that of Mary Mallon (aka Typhoid Mary), a typhoid fever carrier who spent the last 24 years of her life under quarantine.

Quarantine periods can be very short, such as in the case of a suspected anthrax attack, in which persons are allowed to leave as soon as they shed their potentially contaminated garments and undergo a decontamination shower. For example, an article entitled "Daily News workers quarantined" describes a brief quarantine that lasted until people could be showered in a decontamination tent. (Kelly Nankervis, Daily News).

The February/March 2003 issue of HazMat Magazine suggests that people be "locked in a room until proper decon could be performed", in the event of "suspect anthrax".

Standard-Times senior correspondent Steve Urbon (14 February 2003) describes such temporary quarantine powers:

Civil rights activists in some cases have objected to people being rounded up, stripped and showered against their will. But Capt. Chmiel said local health authorities have "certain powers to quarantine people."

The purpose of such quarantine-for-decontamination is to prevent the spread of contamination, and to contain the contamination such that others are not put at risk from a person fleeing a scene where contamination is suspect. It can also be used to limit exposure, as well as eliminate a vector.

The first astronauts to visit the Moon were quarantined upon their return at the specially built Lunar Receiving Laboratory.

New developments for quarantine include new concepts in quarantine vehicles such as the ambulance bus, mobile hospitals, and lockdown/invacuation (inverse evacuation) procedures, as well as docking stations for an ambulance bus to dock to a facility that's under lockdown.

History

Infected people were separated to prevent spread of disease among the ancient Israelites under the Mosaic Law, as recorded in the Old Testament.[5]

The word "quarantine" originates from the Venetian dialect form of the Italian quaranta giorni, meaning 'forty days'. This is due to the 40 day isolation of ships and people before entering the city of Dubrovnik in Croatia. This was practised as a measure of disease prevention related to the Black Death. Between 1348 and 1359, the Black Death wiped out an estimated 30% of Europe's population, and a significant percentage of Asia's population. The original document from 1377, which is kept in the Archives of Dubrovnik, states that before entering the city, newcomers had to spend 30 days (a trentine) in a restricted place (originally nearby islands) waiting to see whether the symptoms of Black Death would develop. Later, isolation was prolonged to 40 days and was called quarantine.[6]

Other diseases lent themselves to the practice of quarantine before and after the devastation of the plague. Those afflicted with leprosy were historically isolated from society, as were the attempts to check the invasion of syphilis in northern Europe in about 1490, the advent of yellow fever in Spain at the beginning of the 19th century, and the arrival of Asiatic cholera in 1831.

Venice took the lead in measures to check the spread of plague, having appointed three guardians of public health in the first years of the Black Death (1348). The next record of preventive measures comes from Reggio in Modena in 1374. The first lazaret was founded by Venice in 1403, on a small island adjoining the city. In 1467, Genoa followed the example of Venice, and in 1476 the old leper hospital of Marseille was converted into a plague hospital. The great lazaret of Marseilles, perhaps the most complete of its kind, was founded in 1526 on the island of Pomègues. The practice at all the Mediterranean lazarets was not different from the English procedure in the Levantine and North African trade. On the approach of cholera in 1831 some new lazarets were set up at western ports, notably a very extensive establishment near Bordeaux, afterwards turned to another use.

International conventions

Since 1852 several conferences were held involving European powers, with a view to uniform action in keeping out infection from the East and preventing its spread within Europe. All but that of 1897 were concerned with cholera. No result came of those at Paris (1852), Constantinople (1866), Vienna (1874), and Rome (1885), but each of the subsequent ones doctrine of constructive infection of a ship as coming from a scheduled port, and an approximation to the principles advocated by Great Britain for many years. The principal countries which retained the old system at the time were Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Greece and Russia (the British possessions at the time, Gibraltar, Malta and Cyprus, being under the same influence). The aim of each international sanitary convention had been to bind the governments to a uniform minimum of preventive action, with further restrictions permissible to individual countries. The minimum specified by international conventions was very nearly the same as the British practice, which had been in turn adapted to continental opinion in the matter of the importation of rags.

The Venice convention of 30 January 1892 dealt with cholera by the Suez Canal route; that of Dresden of 15 April 1893, with cholera within European countries; that of Paris of 3 April 1894, with cholera by the pilgrim traffic; and that of Venice, on 19 March 1897, was in connection with the outbreak of plague in the East, and the conference met to settle on an international basis the steps to be taken to prevent, if possible, its spread into Europe. An additional convention was signed in Paris on 3 December 1903.[7]

A multilateral international sanitary convention was concluded at Paris on 17 January 1912.[8] This convention was most comprehensive and was designated to replace all previous conventions on that matter. It was signed by 40 countries, and consisted of 160 articles. Ratifications by 16 of the signatories were exchanged in Paris on 7 October 1920. Another multilateral convention was signed in Paris on 21 June 1926, to replace that of 1912. It was signed by 58 countries worldwide, and consisted of 172 articles.[9]

In Latin America, a series of regional sanitary conventions were concluded. Such a convention was concluded in Rio de Janeiro on 12 June 1904. A sanitary convention between the governments of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay was concluded in Montevideo on 21 April 1914.[10] The convention covers cases of Asiatic cholera, oriental plague and yellow fever. It was ratified by the Uruguayan government on 13 October 1914, by the Paraguayan government on 27 September 1917 and by the Brazilian government on 18 January 1921.

Sanitary conventions were also concluded between European states. A Soviet-Latvian sanitary convention was signed on 24 June 1922, for which ratifications were exchanged on 18 October 1923.[11] A bilateral sanitary convention was concluded between the governments of Latvia and Poland on 7 July 1922, for which ratifications were exchanged on 7 April 1925.[12] Another was concluded between the governments of Germany and Poland in Dresden on 18 December 1922, and entered into effect on 15 February 1923.[13] Another one was signed between the governments of Poland and Romania on 20 December 1922. Ratifications were exchanged on 11 July 1923.[14] The Polish government also concluded such a convention with the Soviet government on 7 February 1923, for which ratifications were exchanged on 8 January 1924.[15] A sanitary convention was also concluded between the governments of Poland and Czechoslovakia on 5 September 1925, for which ratifications were exchanged on 22 October 1926.[16] A convention was signed between the governments of Germany and Latvia on 9 July 1926, for which ratifications were exchanged on 6 July 1927.[17]

One of the first points to be dealt with in 1897 was to settle the incubation period for this disease, and the period to be adopted for administrative purposes. It was admitted that the incubation period was, as a rule, a comparatively short one, namely, of some three or four days. After much discussion ten days was accepted by a very large majority. The principle of disease notification was unanimously adopted. Each government had to notify to other governments on the existence of plague within their several jurisdictions, and at the same time state the measures of prevention which are being carried out to prevent its diffusion. The area deemed to be infected was limited to the actual district or village where the disease prevailed, and no locality was deemed to be infected merely because of the importation into it of a few cases of plague while there has been no diffusion of the malady. As regards the precautions to be taken on land frontiers, it was decided that during the prevalence of plague every country had the inherent right to close its land frontiers against traffic. As regards the Red Sea, it was decided after discussion that a healthy vessel could pass through the Suez Canal, and continue its voyage in the Mediterranean during the period of incubation of the disease the prevention of which is in question. It was also agreed that vessels passing through the Canal in quarantine might, subject to the use of the electric light, coal in quarantine at Port Said by night as well as by day, and that passengers might embark in quarantine at that port. Infected vessels, if these carry a doctor and are provided with a disinfecting stove, have a right to navigate the Canal, in quarantine, subject only to the landing of those who were suffering from plague.

Signals and flags

Plain yellow, green, and even black flags have been used to symbolize disease in both ships and ports, with the color yellow having a longer historical precedent, as a color of marking for houses of infection, previous to its use as a maritime marking color for disease. The present flag used for the purpose is the "Lima" (L) flag, which is a mixture of yellow and black flags previously used. It is sometimes called the "yellow jack" but this was also a name for yellow fever, which probably derives its common name from the flag, not the color of the victims (cholera ships also used a yellow flag).[18] The plain yellow flag ("Quebec" or Q in international maritime signal flags) probably derives its letter symbol for its initial use in quarantine, but this flag in modern times indicates the opposite—a ship that declares itself free of quarantinable disease, and requests boarding and routine port inspection.[19]

Australia

Australia has perhaps the world's strictest quarantine standards. Quarantine in northern Australia is important because of its proximity to South-east Asia and the Pacific, which have many pests and diseases not present in Australia. For this reason, the region from Cairns to Broome—including the Torres Strait—is the focus for many important quarantine activities that protect all Australians.[20] As Australia has been geographically isolated from other major continents for millions of years, there is an endemically unique ecosystem free of several severe pests and diseases that are present in many parts of the world.[21] If other products are brought inside along with pests and diseases, it would damage the ecosystem seriously and add millions of costs in the local agricultural businesses.

The Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service is responsible for border-inspection of any products which are brought into Australia, and assess the potential risks the products might harm Australian environment. Visitors are required to fill in the information card truthfully before arriving in Australia, and declare what food and any products made of wood and other natural materials they have processed. If the visitor fails to do so, usually a quarantine fine of 220 Australian dollars are to be paid as quarantine infringement notice, and if not, the visitor may face criminal convictions of fining 100,000 Australian dollars and 10 years imprisonment.

Canada

There are three quarantine Acts of Parliament in Canada: Quarantine Act (humans) and Health of Animals Act (animals) and Plant Protection Act (vegetations). The first legislation is enforced by the Canada Border Services Agency after a complete rewrite in 2005. The second and third legislations are enforced by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. If a health emergency exists, the Governor in Council can prohibit importation of anything that it deems necessary under the Quarantine Act.

Under the Quarantine Act, all travellers must submit to screening and if they believe they might have come into contact with communicable diseases or vectors, they must disclose their whereabouts to a Border Services Officer. If the officer has reasonable grounds to believe that the traveller is or might have been infected with a communicable disease or refused to provide answers, a quarantine officer (QO) must be called and the person is to be isolated. If a person refuses to be isolated, any peace officer may arrest without warrant.

A QO who has reasonable grounds to believe that the traveller has or might have a communicable disease or is infested with vectors, after the medical examination of a traveller, can order him/her into treatment or measures to prevent the person from spreading the disease. QO can detain any traveller who refuses to comply with his/her orders or undergo health assessments as required by law.

Under the Health of Animals Act and Plant Protection Act, inspectors can prohibit access to an infected area, dispose or treat any infected or suspected to be infected animals or plants. The Minister can order for compensation to be given if animals/plants were destroyed pursuant to these acts.

Each province also enacts its own quarantine/environmental health legislations.

Hong Kong

Under the Prevention and Control of Disease Ordinance (HK Laws. Chap 599), a health officer may seize articles he/she believes to be infectious or contains infectious agents. All travellers, if requested, must submit themselves to a health officer. Failure to do so is against the law and is subject to arrest and prosecution.

The law allows for a health officer who have reasonable grounds to detain, isolate, quarantine anyone or anything believed to be infected and to restrict any articles from leaving a designated quarantine area. He/she may also order the Civil Aviation Department to prohibit the landing or leaving, embarking or disembarking of an aircraft. This power also extends to land, sea or air crossings.

Under the same ordinance, any police officer, health officer, members of the Civil Aid Service or Auxiliary Medical Service can arrest a person who obstructs or escape from detention.

United Kingdom

To reduce the risk of introducing rabies from continental Europe, the United Kingdom used to require that dogs, and most other animals introduced to the country, spend six months in quarantine at an HM Customs and Excise pound; this policy was abolished in 2000 in favour of a scheme generally known as Pet Passports, where animals can avoid quarantine if they have documentation showing they are up to date on their appropriate vaccinations.

British quarantine rules after 1711

The plague had disappeared from England, never to return, for more than thirty years before the practice of quarantine against it was definitely established by the Quarantine Act 1710 (9 Ann.) The first act was called for, owing to an alarm, lest plague should be imported from Poland and the Baltics; the second act of 1721 was due to the disastrous prevalence of plague at Marseille and other places in Provence, France; it was renewed in 1733 owing to a fresh outbreak of the malady on the continent of Europe, and again in 1743, owing to the disastrous epidemic at Messina. In 1752 a rigorous quarantine clause was introduced into an act regulating the Levantine trade; and various arbitrary orders were issued during the next twenty years to meet the supposed danger of infection from the Baltics. Although no plague cases ever came to England all those years, the restrictions on traffic became more and more stringent (following the movements of medical dogma), and in 1788 a very oppressive Quarantine Act was passed, with provisions affecting cargoes in particular. The first year of the nineteenth century marked the turning-point in quarantine legislation; a parliamentary committee sat on the practice, and a more reasonable act arose on their report. In 1805 there was another new act, and in 1823–24 again an elaborate inquiry followed by an act making the quarantine only at discretion of the privy council, and at the same time recognizing yellow fever or other highly infectious disorder as calling for quarantine measures along with plague. The steady approach of cholera in 1831 was the last occasion in England of a thoroughgoing resort to quarantine restrictions. The pestilence invaded every country of Europe despite all efforts to keep it out. In England the experiment of hermetically sealing the ports was not seriously tried when cholera returned in 1849, 1853 and 1865–66. In 1847 the privy council ordered all arrivals with clean bills from the Black Sea and the Levant to be admitted to free pratique, provided there had been no case of plague during the voyage; and therewith the last remnant of the once formidable quarantine practice against plague may be said to have disappeared.

For a number of years after the passing of the first Quarantine Act (1710) the protective practices in England were of the most haphazard and arbitrary kind. In 1721 two vessels laden with cotton goods from Cyprus, then a seat of plague, were ordered to be burned with their cargoes, the owners receiving as indemnity. By the clause in the Levant Trade Act of 1752 vessels for the United Kingdom with a foul bill (i.e. coming from a country where plague existed) had to repair to the lazarets of Malta, Venice, Messina, Livorno, Genoa or Marseille, to perform their quarantine or to have their cargoes sufficiently opened and aired. Since 1741 Stangate Creek (on the Medway) had been made the quarantine station at home; but it would appear from the above clause that it was available only for vessels with clean bills. In 1755 lazarets in the form of floating hulks were established in England for the first time, the cleansing of cargo (particularly by exposure to dews) having been done previously on the ship's deck. There was no medical inspection employed, but the whole routine left to the officers of customs and quarantine. In 1780, when plague was in Poland, even vessels with grain from the Baltic had to lie forty days in quarantine, and unpack and air the sacks; but owing to remonstrances, which came chiefly from Edinburgh and Leith, grain was from that date declared to be a non-susceptible article. About 1788 an order of the council required every ship liable to quarantine, in case of meeting any vessel at sea, or within four leagues of the coast of Great Britain or Ireland, to hoist a yellow flag in the daytime and show a light at the main topmast head at night, under a penalty of After 1800, ships from plague-countries (or with foul bills) were enabled to perform their quarantine on arrival in the Medway instead of taking a Mediterranean port on the way for that purpose; and about the same time an extensive lazaret was built on Chetney Hill near Chatham at an expense of which was almost at once condemned owing to its marshy foundations, and the materials sold for The use of floating hulks as lazarets continued as before. In 1800 two ships with hides from Mogador (Morocco) were ordered to be sunk with their cargoes at the Nore, the owners receiving About this period it was merchandise that was chiefly suspected: there was a long schedule of susceptible articles, and these were first exposed on the ship's deck for twenty-one days or less (six days for each instalment of the cargo), and then transported to the lazaret, where they were opened and aired forty days more. The whole detention of the vessel was from sixty to sixty-five days, including the time for reshipment of her cargo. Pilots had to pass fifteen days on board a convalescent ship. The expenses may be estimated from one or two examples. In 1820 the Asia, 763 tons, arrived in the Medway with a foul bill from Alexandria, laden with linseed; her freight was and her quarantine dues The same year the Pilato, 495 tons, making the same voyage, paid quarantine dues on a freight of In 1823 the expenses of the quarantine service (at various ports) were and the dues paid by shipping (nearly all with clean bills) A return for the United Kingdom and colonies in 1849 showed, among other details, that the expenses of the lazaret at Malta for ten years from 1839 to 1848 had been From 1846 onwards the establishments in the United Kingdom were gradually reduced, while the last vestige of the British quarantine law was removed by the Public Health Act 1896, which repealed the Quarantine Act 1825 (with dependent clauses of other acts), and transferred from the privy council to the Local Government Board the powers to deal with ships arriving infected with yellow fever or plague, the powers to deal with cholera ships having been already transferred by the Public Health Act 1875.

The British regulations of 9 November 1896 applied to yellow fever, plague and cholera. Officers of the Royal Customs, as well as of Royal Coast Guard and Board of Trade (for signalling), were empowered to take the initial steps. They certified in writing the master of a supposed infected ship, and detained the vessel provisionally for not more than twelve hours, giving notice meanwhile to the port sanitary authority. The medical officer of the port boarded the ship and examined every person in it. Every person found infected was certified of the fact, removed to a hospital provided (if his condition allow), and kept under the orders of the medical officer. If the sick could be removed, the vessel remained under his orders. Every person suspected (owing to his or her immediate attendance on the sick) could be detained on board for 48 hours or removed to the hospital for a similar period. All others were free to land on giving the addresses of their destinations to be sent to the respective local authorities, so that the dispersed passengers and crew could be kept individually under observation for a few days. The ship was then disinfected, dead bodies buried at sea, infected clothing, bedding, etc., destroyed or disinfected, and bilge-water and water-ballast (subject to exceptions) pumped out at a suitable distance before the ship entered a dock or basin. Mails were subject to no detention. A stricken ship within 3 miles of the shore had to fly at the main mast a yellow and black flag borne quarterly from sunrise to sunset.

United States

The United States puts immediate quarantines on imported products if the disease can be traced back to a certain shipment or product. All imports will also be quarantined if the diseases breakout in other countries. According to Title 42 U.S.C. §§264 and 266, these statutes provide the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (“the Secretary”) peacetime and wartime authority, respectively, to control the movement of persons into and within the United States to prevent the spread of communicable disease.

Communicable diseases for which apprehension, detention, or conditional release of persons are authorized must be specified in Executive Orders of the President.[22] Executive Order 13295 (Revised List of Quarantinable Communicable Diseases, April 4, 2003) and its amendments (executive orders 13375 and 13674) specify the following infectious diseases: (1) cholera, (2) diphtheria, (3) infectious tuberculosis, (4) plague, (5) smallpox, (6) yellow fever, (7) viral hemorrhagic fevers (Lassa, Marburg, Ebola, Crimean-Congo, South American, and others not yet isolated or named), (8) severe acute respiratory syndromes, and (9) influenza, from a novel or re-emergent source.[23] In the event of conflict of federal, state, local, and/or tribal health authorities in the use of legal quarantine power, federal law is supreme.[24]

The Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ) of the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) operates small quarantine facilities at a number of US ports of entry. As of 2014, these included one land crossing (in El Paso, Texas) and 19 international airports.

- Anchorage

- Atlanta

- Boston

- Chicago

- Dallas/Ft. Worth

- Detroit

- Honolulu

- Houston

- Los Angeles

- Miami

- Minneapolis

- New York JFK

- Newark

- Philadelphia

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- San Juan

- Seattle

- Washington, D.C. (Dulles)

[25] [26] Besides the port of entry where it is located, each station is also responsible for quarantining potentially infected travelers entering through any ports of entry in its assigned region. These facilities are fairly small; each one is operated by a few staff members and capable of accommodating 1-2 travelers for a short observation period.[26] Cost estimates for setting up a temporary larger facility, capable of accommodating 100 to 200 travelers for several weeks, have been published by the Airport Cooperative Research Program in 2008.[26]

United States – history

Quarantine law began in Colonial America in 1663, when in an attempt to curb an outbreak of smallpox, the city of New York established a quarantine. In the 1730s, the city built a quarantine station on the Bedloe's Island.[27] The Philadelphia Lazaretto was the first quarantine hospital in the United States, built in 1799, in Tinicum Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania.[28] There are similar national landmarks such as Swinburne Island and Angel Island (a much more famous historic site, Ellis Island, is often mistakenly assumed to have been a quarantine station, however its marine hospital only qualified as a contagious disease facility to handle less virulent diseases like measles, trachoma and less advanced stages of tuberculosis and diphtheria; persons afflicted with smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, leprosy or typhoid fever, could neither be received nor treated there). During the 1918 flu pandemic, people were also quarantined. Most commonly suspect cases of infectious diseases are requested to voluntarily quarantine themselves, and Federal and local quarantine statutes only have been uncommonly invoked since then, including for a suspected smallpox case in 1963.[29]

In 2007, Andrew Speaker, an Atlanta attorney on his honeymoon in Europe, was diagnosed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB), which is contagious, untreatable, and potentially lethal. Speaker returned to the U.S. against the instructions of the CDC, and he was served with a federal order of quarantine by the CDC at a New York hospital, the first such order to be issued in nearly half a century.[30] Speaker challenged the diagnosis, resulting in a new diagnosis of a milder form of tuberculosis and the lifting of restrictions on his movements. The Speaker case drew significant public attention, and Congress held formal hearings about the incident. Speaker’s case highlighted a vital issue in public health law: the circumstances, if any, under which public officials may detain individuals against their will to protect the public from communicable diseases, and the conflict between the utilitarian principle of social good and the individual rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution.[31]

Also other TB carriers who refuse to wear a mask in public have been indefinitely involuntarily committed to regular jails, and cut off from contacting the world.[32][33] Some have complained of abuse there.[34]

Other uses

U.S. President John F. Kennedy euphemistically referred to the U.S. Navy's interdiction of shipping en route to Cuba during the Cuban missile crisis as a "quarantine" rather than a blockade, because a quarantine is a legal act in peacetime, whereas a blockade is defined as an act of aggression under the U.N. Charter.

In computer science, "quarantining" describes putting files infected by computer viruses into a special directory, so as to eliminate the threat they pose, without irreversibly deleting them.

Notable quarantines

- Eyam was a village in Britain that chose to isolate itself to stop the spread of the plague northward in 1665. They were hindered in this by the time's limited knowledge of the disease: what caused it, what forms infection took, what animal vectors carried it, how it spread.

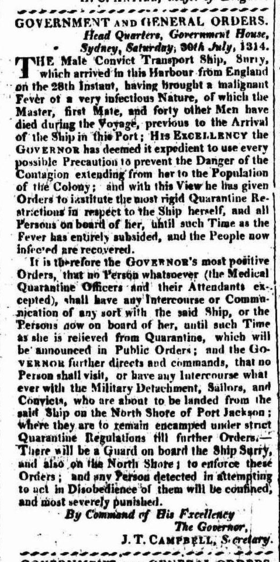

- On 28 July 1814 the convict ship Surry arrived in Sydney Harbour from England. Over 40 persons had died of typhoid during the voyage including 36 convicts. The ship was placed in quarantine on the North Shore. Convicts were landed and a camp established in the immediate vicinity of what is now Jeffrey Street in Kirribilli. This was the first site in Australia to be used for quarantine purposes.[35]

- Typhoid Mary was quarantined in New York in the early twentieth century. She was an asymptomatic typhoid carrier and was considered a public health hazard.

- In 1942, during World War II, British forces tested out their biological weapons programme on Gruinard Island and infected it with anthrax. The quarantine was lifted in 1990 when the island was declared safe and a flock of sheep were released onto the island.

- The astronauts on Apollo 11 were put into quarantine for a couple of weeks in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory to make sure that they didn't carry any unknown diseases from the moon. The fear of a interplanetary contamination by back contamination from the Moon was the main reason for quarantine procedures adopted for the early Apollo program. Astronauts and lunar samples were quarantined in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory.

- The 1972 outbreak of smallpox in Yugoslavia was the final outbreak of smallpox in Europe. The WHO fought the outbreak with extensive quarantine, and the government instituted martial law.

- Robert Daniels was quarantined in 2007 for having the deadliest form of tuberculosis in an Arizona hospital, partly for not wearing a mask during his time in the outside world when he was diagnosed with the disease.[36]

- Andrew Speaker was placed under U.S. federal quarantine in 2007 after flying to Europe while knowing he had tuberculosis, then flying back after learning it was an extensively drug resistant strain. He is the first person since 1963 to be under federal quarantine.

Quarantine in fiction and popular culture

- Quarantine (video game), a 1994 video game for the 3DO and IBM PC systems

- Quarantine (2000 film), a 2000 American thriller television film

- Quarantine (2008 film), a 2008 science fiction horror film

- Quarantine (Greg Egan novel), a 1992 science fiction novel by Greg Egan

- Quarantine (Jim Crace novel), a 1997 novel by Jim Crace

- "Quarantine", a 1986 episode of the 1980s Twilight Zone

See also

- Extra-Terrestrial Exposure Law

- Isolation (health care)

- Lazaretto

- Pesthouse

- Protective sequestration

- Cordon sanitaire

List of quarantine services in the world

- Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service

- MAF Quarantine Service, in the New Zealand

- Quarantine, Western Australia for the Western Australian Government

- Samoa Quarantine Service, in the West Samoa

- Racehorse & Equine Quarantine Services, A Company Build & Developed by Frankie Thevarasa Kuala Lumpur Malaysia

References

- ↑ Merriam Webster definition | http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/quarantine

- ↑ (Cited from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/)

- ↑ Cited from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/

- ↑ Ronald Eccles, Olaf Weber, ed. (2009). Common cold (Online-Ausg. ed.). Basel: Birkhäuser. p. 210. ISBN 978-3-7643-9894-1.

- ↑ "If the shiny spot on the skin is white but does not appear to be more than skin deep and the hair in it has not turned white, the priest is to isolate the affected person for seven days. On the seventh day the priest is to examine them, and if he sees that the sore is unchanged and has not spread in the skin, he is to isolate them for another seven days." Lev. 15/4-5.

- ↑ Sehdev, Paul S. (2002). "The Origin of Quarantine". Clinical Infectious Diseases 35 (9): 1071–1072. doi:10.1086/344062. PMID 12398064.

- ↑ Text of the 1903 convention, from the website of the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 4, pp. 282–413.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 78, pp. 230–349.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 5, pp. 394–441.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 38, pp. 10–55.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 37, pp. 318–339.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vo. 34, pp. 302–313.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 18, pp. 104–119.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 49, pp. 286–314.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 58, pp. 144–177.

- ↑ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 63, pp. 322–361.

- ↑ Sehdev PS (November 2002). "The origin of quarantine". Clin. Infect. Dis. 35 (9): 1071–2. doi:10.1086/344062. PMID 12398064.

- ↑ quarantine mark history

- ↑ http://www.daff.gov.au/aqis/about/public-awareness

- ↑ "Quarantine in Australia - Department of Agriculture". daff.gov.au. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ↑ "Regulations to control communicable diseases". gpo.gov. Retrieved 30 Oct 2014.

- ↑ "Specific Laws and Regulations Governing the Control of Communicable Diseases". cdc.gov. bottom of page, in "Executive Orders" paragraph. 31 July 2014.

- ↑ Schultz, edited by Kristi Koenig, Carl (2009). Koenig and Schultz's disaster medicine : comprehensive principles and practices. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780521873673.

- ↑ Quarantine Station Contact List, Map, and Fact Sheets (CDC)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Stambaugh, Hollis; Sensenig, Daryl; Casagrande, Rocco; Flagg, Shania; Gerrity, Bruce (2008), Quarantine Facilities for Arriving Air Travelers: Identification of Planning Needs and Costs (PDF), TRB’s Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP) Report 5

- ↑ "Lazaretto Quarantine Station, Tinicum Township, Delaware County, PA: History". ushistory.org. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ↑ "Contagious Disease Control, The Lazaretto". City of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ↑ "Get In That Bubble, Boy! When can the government quarantine its citizens?". Slate magazine. 1 June 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

In fact, until this recent situation, the CDC hadn't issued such an order since 1963, when it quarantined a woman for smallpox exposure. Even during the SARS epidemic in 2003, officials relied mostly on voluntary isolation and quarantine. And the last large-scale quarantine in the U.S. took place during the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918–19. ...

- ↑ Meena Hartenstein, Timeline of Speaker’s TB Odyssey, abcnews.com (1 Jun. 2007) (available at http://abcnews.go.com/US/story?id=3235763&page=1) (Speaker was diagnosed with tuberculosis after receiving a chest x-ray in connection with a bruised rib)

- ↑ Jorge L. Contreras, "Public Health versus Personal Liberty – the Uneasy Case for Individual Detention, Isolation and Quarantine", The SciTech Lawyer, Vol. 7, Issue 4 (Spring 2011)

- ↑ "Man Isolated with Deadly Tuberculosis Strain". NPR.

- ↑ "Drug-proof TB strain poses ethical bind - Health - Infectious diseases _ NBC News.htm".

- ↑ "TB Patient Flees U.S. "Abuse" For Russia".

- ↑ Secretary's Office, Sydney (10 September 1814). "The Sydney Gazette, and New South Wales Advertiser". Government Public Notice. Published by Authority. p. 2. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ NPR.org

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quarantine. |

| Look up quarantine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Ayliffe GAJ, English MP, Hospital infection, From Miasmas to MRSA, Cambridge University Press, 2003

- Frati P: Quarantine, trade and health policies in Ragusa-Dubrovnik until the age of George Armmenius-Baglivi. Med Secoli. 2000;12(1):103-27.

- Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol.8, No.1

- History of quarantine (from PBS NOVA)

- Articles Critical Of Bird Flu Quarantine Efforts From Age Of Tyranny News+

- Federal and State Quarantine and Isolation Authority Congressional Research Service

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.