Quantum dot

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

| Fullerenes |

| Nanoparticles |

|

|

A quantum dot (QD) is a nanocrystal made of semiconductor materials that is small enough to exhibit quantum mechanical properties. Specifically, its excitons are confined in all three spatial dimensions. The electronic properties of these materials are intermediate between those of bulk semiconductors and of discrete molecules.[1][2][3] Quantum dots were discovered by Alexey Ekimov at first in 1981[4][5][6] in a glass matrix and then in colloidal solutions by Louis E. Brus in 1985.[7] The term "quantum dot" was coined by Mark Reed.[8]

Researchers have studied applications for quantum dots in transistors, solar cells, LEDs, and diode lasers. They have also investigated quantum dots as agents for medical imaging and as possible qubits in quantum computing. The first commercial release of a product utilizing quantum dots was the Sony XBR X900A series of flat panel televisions released in 2013.[9]

Electronic characteristics of a quantum dot are closely related to its size and shape. For example, the band gap in a quantum dot which determines the frequency range of emitted light is inversely related to its size. In fluorescent dye applications the frequency of emitted light increases as the size of the quantum dot decreases. Consequently, the color of emitted light shifts from red to blue when the size of the quantum dot is made smaller.[10] This allows the excitation and emission of quantum dots to be highly tunable. Since the size of a quantum dot may be set when it is made, its conductive properties may be carefully controlled. Quantum dot assemblies consisting of many different sizes, such as gradient multi-layer nanofilms, can be made to exhibit a range of desirable emission properties.

Quantum confinement in semiconductors

In a semiconductor crystallite whose radius is smaller than the size of its exciton Bohr radius, the excitons are squeezed, leading to quantum confinement. The energy levels can then be modeled using the particle in a box model in which the energy of different states is dependent on the length of the box. Quantum dots are said to be in the 'weak confinement regime' if their radii are on the order of the exciton Bohr radius; quantum dots are said to be in the 'strong confinement regime' if their radii are smaller than the exciton Bohr radius. If the size of the quantum dot is small enough that the quantum confinement effects dominate (typically less than 10 nm), the electronic and optical properties are highly tunable.

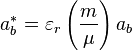

Fluorescence occurs when an excited electron relaxes to the ground state and combines with the hole. In a simplified model, the energy of the emitted photon can be understood as the sum of the band gap energy between the occupied level and the unoccupied energy level, the confinement energies of the hole and the excited electron, and the bound energy of the exciton (the electron-hole pair):

- Band gap energy

- The band gap can become larger in the strong confinement regime where the size of the quantum dot is smaller than the Exciton Bohr radius ab* as the energy levels split up.

- where ab is the Bohr radius=0.053 nm, m is the mass, μ is the reduced mass, and εr is the size-dependent dielectric constant (Relative permittivity).

- This results in the increase in the total emission energy (the sum of the energy levels in the smaller band gaps in the strong confinement regime is larger than the energy levels in the band gaps of the original levels in the weak confinement regime) and the emission at various wavelengths; which is precisely what happens in the sun, where the quantum confinement effects are completely dominant and the energy levels split up to the degree that the energy spectrum is almost continuous, thus emitting white light.

- Confinement energy

- The exciton entity can be modeled using the particle in the box. The electron and the hole can be seen as hydrogen in the Bohr model with the hydrogen nucleus replaced by the hole of positive charge and negative electron mass. Then the energy levels of the exciton can be represented as the solution to the particle in a box at the ground level (n = 1) with the mass replaced by the reduced mass. Thus by varying the size of the quantum dot, the confinement energy of the exciton can be controlled.

- Bound exciton energy

- There is Coulomb attraction between the negatively charged electron and the positively charged hole. The negative energy involved in the attraction is proportional to Rydberg's energy and inversely proportional to square of the size-dependent dielectric constant[11] of the semiconductor. When the size of the semiconductor crystal is smaller than the Exciton Bohr radius, the Coulomb interaction must be modified to fit the situation.

Therefore, the sum of these energies can be represented as:

where μ is the reduced mass, a is the radius, me is the free electron mass, mh is the hole mass, and εr is the size-dependent dielectric constant.

Although the above equations were derived using simplifying assumptions, the implications are clear; the energy of the quantum dots is dependent on their size due to the quantum confinement effects, which dominate below the critical size leading to changes in the optical properties. This effect of quantum confinement on the quantum dots has been experimentally verified[12] and is a key feature of many emerging electronic structures.[13][14]

Besides confinement in all three dimensions (i.e., a quantum dot), other quantum confined semiconductors include:

- Quantum wires, which confine electrons or holes in two spatial dimensions and allow free propagation in the third.

- Quantum wells, which confine electrons or holes in one dimension and allow free propagation in two dimensions.

Production

There are several ways to confine excitons in semiconductors, resulting in different methods to produce quantum dots. In general, quantum wires, wells and dots are grown by advanced epitaxial techniques in nanocrystals produced by chemical methods or by ion implantation, or in nanodevices made by state-of-the-art lithographic techniques.[15]

Colloidal synthesis

Colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals are synthesized from precursor compounds dissolved in solutions, much like traditional chemical processes. The synthesis of colloidal quantum dots is done by using precursors,[3] organic surfactants,[16] and solvents. Heating the solution at high temperature, the precursors decompose forming monomers which then nucleate and generate nanocrystals. The temperature during the synthetic process is a critical factor in determining optimal conditions for the nanocrystal growth. It must be high enough to allow for rearrangement and annealing of atoms during the synthesis process while being low enough to promote crystal growth. The concentration of monomers is another critical factor that has to be stringently controlled during nanocrystal growth. The growth process of nanocrystals can occur in two different regimes, "focusing" and "defocusing". At high monomer concentrations, the critical size (the size where nanocrystals neither grow nor shrink) is relatively small, resulting in growth of nearly all particles. In this regime, smaller particles grow faster than large ones (since larger crystals need more atoms to grow than small crystals) resulting in "focusing" of the size distribution to yield nearly monodisperse particles. The size focusing is optimal when the monomer concentration is kept such that the average nanocrystal size present is always slightly larger than the critical size. Over time, the monomer concentration diminishes, the critical size becomes larger than the average size present, and the distribution "defocuses".

There are colloidal methods to produce many different semiconductors. Typical dots are made of binary compounds such as lead sulfide, lead selenide, cadmium selenide, cadmium sulfide, indium arsenide, and indium phosphide. Dots may also be made from ternary compounds such as cadmium selenide sulfide. These quantum dots can contain as few as 100 to 100,000 atoms within the quantum dot volume, with a diameter of 10 to 50 atoms. This corresponds to about 2 to 10 nanometers, and at 10 nm in diameter, nearly 3 million quantum dots could be lined up end to end and fit within the width of a human thumb.

_with_complete_passivation.png)

Large batches of quantum dots may be synthesized via colloidal synthesis. Due to this scalability and the convenience of benchtop conditions, colloidal synthetic methods are promising for commercial applications. It is acknowledged to be the least toxic of all the different forms of synthesis.

Fabrication

- Self-assembled quantum dots are typically between 5 and 50 nm in size. Quantum dots defined by lithographically patterned gate electrodes, or by etching on two-dimensional electron gases in semiconductor heterostructures can have lateral dimensions between 20 and 100 nm.

- Some quantum dots are small regions of one material buried in another with a larger band gap. These can be so-called core–shell structures, e.g., with CdSe in the core and ZnS in the shell or from special forms of silica called ormosil.

- Quantum dots sometimes occur spontaneously in quantum well structures due to monolayer fluctuations in the well's thickness.

- Self-assembled quantum dots nucleate spontaneously under certain conditions during molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) and metallorganic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE), when a material is grown on a substrate to which it is not lattice matched. The resulting strain produces coherently strained islands on top of a two-dimensional wetting layer. This growth mode is known as Stranski–Krastanov growth. The islands can be subsequently buried to form the quantum dot. This fabrication method has potential for applications in quantum cryptography (i.e. single photon sources) and quantum computation. The main limitations of this method are the cost of fabrication and the lack of control over positioning of individual dots.

- Individual quantum dots can be created from two-dimensional electron or hole gases present in remotely doped quantum wells or semiconductor heterostructures called lateral quantum dots. The sample surface is coated with a thin layer of resist. A lateral pattern is then defined in the resist by electron beam lithography. This pattern can then be transferred to the electron or hole gas by etching, or by depositing metal electrodes (lift-off process) that allow the application of external voltages between the electron gas and the electrodes. Such quantum dots are mainly of interest for experiments and applications involving electron or hole transport, i.e., an electrical current.

- The energy spectrum of a quantum dot can be engineered by controlling the geometrical size, shape, and the strength of the confinement potential. Also, in contrast to atoms, it is relatively easy to connect quantum dots by tunnel barriers to conducting leads, which allows the application of the techniques of tunneling spectroscopy for their investigation.

The quantum dot absorption features correspond to transitions between discrete,three-dimensional particle in a box states of the electron and the hole, both confined to the same nanometer-size box.These discrete transitions are reminiscent of atomic spectra and have resulted in quantum dots also being called artificial atoms.[17]

- Confinement in quantum dots can also arise from electrostatic potentials (generated by external electrodes, doping, strain, or impurities).

- CMOS technology can be employed to fabricate silicon quantum dots. Ultra small (L=20 nm, W=20 nm) CMOS transistors behave as single electron quantum dots when operated at cryogenic temperature over a range of −269 °C (4 K) to about −258 °C (15 K). The transistor displays Coulomb blockade due to progressive charging of electrons one by one. The number of electrons confined in the channel is driven by the gate voltage, starting from an occupation of zero electrons, and it can be set to 1 or many.[18]

Viral assembly

Lee et al. (2002) reported using genetically engineered M13 bacteriophage viruses to create quantum dot biocomposite structures.[19] As a background to this work, it has previously been shown that genetically engineered viruses can recognize specific semiconductor surfaces through the method of selection by combinatorial phage display.[20] Additionally, it is known that liquid crystalline structures of wild-type viruses (Fd, M13, and TMV) are adjustable by controlling the solution concentrations, solution ionic strength, and the external magnetic field applied to the solutions. Consequently, the specific recognition properties of the virus can be used to organize inorganic nanocrystals, forming ordered arrays over the length scale defined by liquid crystal formation. Using this information, Lee et al. (2000) were able to create self-assembled, highly oriented, self-supporting films from a phage and ZnS precursor solution. This system allowed them to vary both the length of bacteriophage and the type of inorganic material through genetic modification and selection.

Electrochemical assembly

Highly ordered arrays of quantum dots may also be self-assembled by electrochemical techniques. A template is created by causing an ionic reaction at an electrolyte-metal interface which results in the spontaneous assembly of nanostructures, including quantum dots, onto the metal which is then used as a mask for mesa-etching these nanostructures on a chosen substrate.

Bulk-manufacture

Quantum dot manufacturing relies on a process called "high temperature dual injection" which has been scaled by multiple companies for commercial applications that require large quantities (hundreds of kilograms to tonnes) of quantum dots. This is a reproducible production method that can be applied to a wide range of quantum dot sizes and compositions.

The bonding in certain cadmium-free quantum dots, such as III-V-based quantum dots, is more covalent than that in II-VI materials, therefore it is more difficult to separate nanoparticle nucleation and growth via a high temperature dual injection synthesis. An alternative method of quantum dot synthesis, the “molecular seeding” process, provides a reproducible route to the production of high quality quantum dots in large volumes. The process utilises identical molecules of a molecular cluster compound as the nucleation sites for nanoparticle growth, thus avoiding the need for a high temperature injection step. Particle growth is maintained by the periodic addition of precursors at moderate temperatures until the desired particle size is reached.[21] The molecular seeding process is not limited to the production of cadmium-free quantum dots; for example, the process can be used to synthesise kilogram batches of high quality II-VI quantum dots in just a few hours.

Another approach for the mass production of colloidal quantum dots can be seen in the transfer of the well-known hot-injection methodology for the synthesis to a technical continuous flow system. The batch-to-batch variations arising from the needs during the mentioned methodology can be overcome by utilizing technical components for mixing and growth as well as transport and temperature adjustments. For the production of CdSe based semiconductor nanoparticles this method has been investigated and tuned to production amounts of kg per month. Since the use of technical components allows for easy interchange in regards of maximum through-put and size, it can be further enhanced to tens or even hundreds of kilograms.[22]

Recently a consortium of U.S. and Dutch companies reported a "milestone" in high volume quantum dot manufacturing by applying the traditional high temperature dual injection method to a flow system.[23] However as of 2011, applications using bulk-manufactured quantum dots are scarcely available.[24]

Heavy metal-free quantum dots

In many regions of the world there is now a restriction or ban on the use of heavy metals in many household goods, which means that most cadmium based quantum dots are unusable for consumer-goods applications.

For commercial viability, a range of restricted, heavy metal-free quantum dots has been developed showing bright emissions in the visible and near infra-red region of the spectrum and have similar optical properties to those of CdSe quantum dots. Among these systems are InP/ZnS and CuInS/ZnS, for example.

Peptides are being researched as potential quantum dot material.[25] Since peptides occur naturally in all organisms, such dots would likely be nontoxic and easily biodegraded.

Environmental impact

The environmental impact of bulk manufacturing and consumption of quantum dots is currently undergoing studies in both private and public labs.

Optical properties

An immediate optical feature of colloidal quantum dots is their color. While the material which makes up a quantum dot defines its intrinsic energy signature, the nanocrystal's quantum confined size is more significant at energies near the band gap. Thus quantum dots of the same material, but with different sizes, can emit light of different colors. The physical reason is the quantum confinement effect.

The larger the dot, the redder (lower energy) its fluorescence spectrum. Conversely, smaller dots emit bluer (higher energy) light. The coloration is directly related to the energy levels of the quantum dot. Quantitatively speaking, the bandgap energy that determines the energy (and hence color) of the fluorescent light is inversely proportional to the size of the quantum dot. Larger quantum dots have more energy levels which are also more closely spaced. This allows the quantum dot to absorb photons containing less energy, i.e., those closer to the red end of the spectrum. Recent articles in Nanotechnology and in other journals have begun to suggest that the shape of the quantum dot may be a factor in the coloration as well, but as yet not enough information is available. Furthermore, it was shown [26] that the lifetime of fluorescence is determined by the size of the quantum dot. Larger dots have more closely spaced energy levels in which the electron-hole pair can be trapped. Therefore, electron-hole pairs in larger dots live longer causing larger dots to show a longer lifetime.

As with any crystalline semiconductor, a quantum dot's electronic wave functions extend over the crystal lattice. Similar to a molecule, a quantum dot has both a quantized energy spectrum and a quantized density of electronic states near the edge of the band gap.

Quantum dots can be synthesized with larger (thicker) shells (CdSe quantum dots with CdS shells). The shell thickness has shown direct correlation to the spectroscopic properties of the particles like lifetime and emission intensity, but also to the stability.

Applications

Quantum dots are particularly significant for optical applications due to their high extinction coefficient.[27] In electronic applications they have been proven to operate like a single electron transistor and show the Coulomb blockade effect. Quantum dots have also been suggested as implementations of qubits for quantum information processing.

The ability to tune the size of quantum dots is advantageous for many applications. For instance, larger quantum dots have a greater spectrum-shift towards red compared to smaller dots, and exhibit less pronounced quantum properties. Conversely, the smaller particles allow one to take advantage of more subtle quantum effects.

Being one-dimensional, quantum dots have a sharper density of states than higher-dimensional structures. As a result, they have superior transport and optical properties, and are being researched for use in diode lasers, amplifiers, and biological sensors. Quantum dots may be excited within a locally enhanced electromagnetic field produced by gold nanoparticles, which can then be observed from the surface plasmon resonance in the photoluminescent excitation spectrum of (CdSe)ZnS nanocrystals. High-quality quantum dots are well suited for optical encoding and multiplexing applications due to their broad excitation profiles and narrow/symmetric emission spectra. The new generations of quantum dots have far-reaching potential for the study of intracellular processes at the single-molecule level, high-resolution cellular imaging, long-term in vivo observation of cell trafficking, tumor targeting, and diagnostics.

Computing

Quantum dot technology is one of the most promising candidates for use in solid-state quantum computation. By applying small voltages to the leads, the flow of electrons through the quantum dot can be controlled and thereby precise measurements of the spin and other properties therein can be made. With several entangled quantum dots, or qubits, plus a way of performing operations, quantum calculations and the computers that would perform them might be possible.

Biology

In modern biological analysis, various kinds of organic dyes are used. However, with each passing year, more flexibility is being required of these dyes, and the traditional dyes are often unable to meet the expectations.[29] To this end, quantum dots have quickly filled in the role, being found to be superior to traditional organic dyes on several counts, one of the most immediately obvious being brightness (owing to the high extinction co-efficient combined with a comparable quantum yield to fluorescent dyes[30]) as well as their stability (allowing much less photobleaching). It has been estimated that quantum dots are 20 times brighter and 100 times more stable than traditional fluorescent reporters.[29] For single-particle tracking, the irregular blinking of quantum dots is a minor drawback. However there have been groups which have developed quantum dots which are essentially nonblinking and demonstated their utility in single molecule tracking experiments.[31][32]

The usage of quantum dots for highly sensitive cellular imaging has seen major advances over the past decade.[33] The improved photostability of quantum dots, for example, allows the acquisition of many consecutive focal-plane images that can be reconstructed into a high-resolution three-dimensional image.[34] Another application that takes advantage of the extraordinary photostability of quantum dot probes is the real-time tracking of molecules and cells over extended periods of time.[35] Antibodies, streptavidin,[36] peptides,[37] DNA,[38] nucleic acid aptamers,[39] or small-molecule ligands [16] can be used to target quantum dots to specific proteins on cells. Researchers were able to observe quantum dots in lymph nodes of mice for more than 4 months.[40]

Semiconductor quantum dots have also been employed for in vitro imaging of pre-labeled cells. The ability to image single-cell migration in real time is expected to be important to several research areas such as embryogenesis, cancer metastasis, stem cell therapeutics, and lymphocyte immunology.

One particular application of Quantum dots in biology is as donor fluorophores in Förster resonance energy transfer, where the large extinction coefficient and spectral purity of these fluorophores make them superior to molecular fluorophores[41] It is also worth noting that the broad absorbance of QDs allows selective excitation of the QD donor and a minimum excitation of a dye acceptor in FRET-based studies.[42] The applicability of the FRET model, which assumes that the Quantum Dot can be approximated as a point dipole, has recently been demonstrated[43]

Scientists have proven that quantum dots are dramatically better than existing methods for delivering a gene-silencing tool, known as siRNA, into cells.[44]

First attempts have been made to use quantum dots for tumor targeting under in vivo conditions. There exist two basic targeting schemes: active targeting and passive targeting. In the case of active targeting, quantum dots are functionalized with tumor-specific binding sites to selectively bind to tumor cells. Passive targeting uses the enhanced permeation and retention of tumor cells for the delivery of quantum dot probes. Fast-growing tumor cells typically have more permeable membranes than healthy cells, allowing the leakage of small nanoparticles into the cell body. Moreover, tumor cells lack an effective lymphatic drainage system, which leads to subsequent nanoparticle-accumulation.

One of the remaining issues with quantum dot probes is their potential in vivo toxicity. For example, CdSe nanocrystals are highly toxic to cultured cells under UV illumination. The energy of UV irradiation is close to that of the covalent chemical bond energy of CdSe nanocrystals. As a result, semiconductor particles can be dissolved, in a process known as photolysis, to release toxic cadmium ions into the culture medium. In the absence of UV irradiation, however, quantum dots with a stable polymer coating have been found to be essentially nontoxic.[40][45] Hydrogel encapsulation of quantum dots allows for quantum dots to be introduced into a stable aqueous solution, reducing the possibility of cadmium leakage.Then again, only little is known about the excretion process of quantum dots from living organisms.[46] These and other questions must be carefully examined before quantum dot applications in tumor or vascular imaging can be approved for human clinical use.

Another potential cutting-edge application of quantum dots is being researched, with quantum dots acting as the inorganic fluorophore for intra-operative detection of tumors using fluorescence spectroscopy.

Delivery of undamaged quantum dots to the cell cytoplasm has been a challenge with existing techniques. Vector-based methods have resulted in aggregation and endosomal sequestration of quantum dots while electroporation can damage the semi-conducting particles and aggregate delivered dots in the cytosol. Cell squeezing – a method invented in 2013 by Armon Sharei, Robert Langer and Klavs Jensen at MIT – has demonstrated efficient cytosolic delivery of quantum dots without inducing aggregation, trapping material in endosomes, or significant loss of cell viability. Moreover, it has shown that individual quantum dots delivered by this approach are detectable in the cell cytosol, thus illustrating the potential of this technique for single molecule tracking studies. These results indicate that Cell squeezing could potentially be implemented as a robust platform for quantum dot based imaging in a variety of applications.[47]

Photovoltaic devices

Quantum dots may be able to increase the efficiency and reduce the cost of today's typical silicon photovoltaic cells. According to an experimental proof from 2004,[48] quantum dots of lead selenide can produce more than one exciton from one high energy photon via the process of carrier multiplication or multiple exciton generation (MEG). This compares favorably to today's photovoltaic cells which can only manage one exciton per high-energy photon, with high kinetic energy carriers losing their energy as heat. Quantum dot photovoltaics would theoretically be cheaper to manufacture, as they can be made "using simple chemical reactions."

Light emitting devices

There are several proposed methods for using quantum dots to improve existing light-emitting diode (LED) design, including "Quantum Dot Light Emitting Diode" (QD-LED) displays and "Quantum Dot White Light Emitting Diode" (QD-WLED) displays. Because Quantum dots naturally produce monochromatic light, they can be more efficient than light sources which must be color filtered. QD-LEDs can be fabricated on a silicon substrate, which allows them to be integrated onto standard silicon-based integrated circuits or microelectromechanical systems.[49] Quantum dots are valued for displays, because they emit light in very specific gaussian distributions. This can result in a display with visibly more accurate colors. A conventional color liquid crystal display (LCD) is usually backlit by fluorescent lamps (CCFLs) or conventional white LEDs that are color filtered to produce red, green, and blue pixels. An improvement is using a conventional blue-emitting LED as light source and converting part of the emitted light into pure green and red light by the appropriate quantum dots placed in front of the blue LED. This type of white light as the backlight of an LCD panel allows for the best color gamut at lower cost than a RGB LED combination using three LEDs.

In June 2006, QD Vision announced technical success in making a proof-of-concept quantum dot display and show a bright emission in the visible and near infra-red region of the spectrum. A QD-LED integrated at a scanning microscopy tip was used to demonstrate fluorescence near-field scanning optical microscopy (NSOM) imaging.[50] Additionally, since the discovery of "white-light emitting" QD, general solid-state lighting applications appear closer than ever.[51]

Photodetector devices

Quantum dot photodetectors (QDPs) can be fabricated either via solution-processing,[52] or from conventional single-crystalline semiconductors.[53] Conventional single-crystalline semiconductor QDPs are precluded from integration with flexible organic electronics due to the incompatibility of their growth conditions with the process windows required by organic semiconductors. On the other hand, solution-processed QDPs can be readily integrated with an almost infinite variety of substrates, and also postprocessed atop other integrated circuits. Such colloidal QDPs have potential applications in surveillance, machine vision, industrial inspection, spectroscopy, and fluorescent biomedical imaging.

Theoretical Models

A variety of theoretical frameworks exist to model optical, electronic, and structural properties of quantum dots. These may be broadly divided into quantum mechanical, semiclassical, and classical.

Quantum Mechanics

Quantum mechanical models and simulations of quantum dots often involve the interaction of electrons with a pseudopotential or random matrix.[54]

Semiclassical

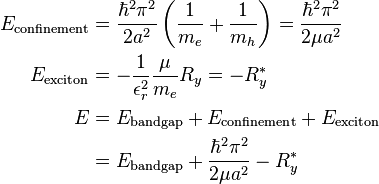

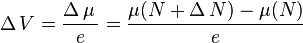

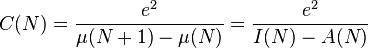

Semiclassical models of quantum dots frequently incorporate a chemical potential. For example, The thermodynamic chemical potential of an N-particle system is given by

whose energy terms may be obtained as solutions of the Schrödinger equation. The definition of capacitance,

,

,

with the potential difference

may be applied to a quantum dot with the addition or removal of individual electrons,

and

and  .

.

Then

is the "quantum capacitance" of a quantum dot, where we denoted by I(N) the ionization potential and by A(N) the electron affinity of the N-particle system.[55]

Classical Mechanics

Classical models of electrostatic properties of electrons in quantum dots are similar in nature to the Thomson problem of optimally distributing electrons on a unit sphere.

The classical electrostatic treatment of electrons confined to spherical quantum dots is similar to their treatment in the Thomson,[56] or plum pudding model, of the atom.[57]

The classical treatment of both two-dimensional and three-dimensional quantum dots exhibit electron shell-filling behavior. A "periodic table of classical artificial atoms" has been described for two-dimensional quantum dots.[58] As well, several connections have been reported between the three-dimensional Thomson problem and electron shell-filling patterns found in naturally-occurring atoms found throughout the periodic table.[59] This latter work originated in classical electrostatic modeling of electrons in a spherical quantum dot represented by an ideal dielectric sphere.[60]

See also

References

- ↑ Brus, L.E. (2007). "Chemistry and Physics of Semiconductor Nanocrystals" (PDF). Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ Norris, D.J. (1995). "Measurement and Assignment of the Size-Dependent Optical Spectrum in Cadmium Selenide (CdSe) Quantum Dots, PhD thesis, MIT". hdl:1721.1/11129.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Murray, C. B.; Kagan, C. R.; Bawendi, M. G. (2000). "Synthesis and Characterization of Monodisperse Nanocrystals and Close-Packed Nanocrystal Assemblies". Annual Review of Materials Research 30 (1): 545–610. Bibcode:2000AnRMS..30..545M. doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.30.1.545.

- ↑ Екимов АИ, Онущенко АА (1981). "Квантовый размерный эффект в трехмерных микрокристаллах полупроводников" (PDF). Письма в ЖЭТФ 34: 363–366.

- ↑ Ekimov AI, Onushchenko AA (1982). "Quantum size effect in the optical-spectra of semiconductor micro-crystals". Soviet Physics Semiconductors-USSR 16 (7): 775–778.

- ↑ Ekimov AI, Efros AL, Onushchenko AA (1985). "Quantum size effect in semiconductor microcrystals". Solid State Communications 56 (11): 921–924. Bibcode:1985SSCom..56..921E. doi:10.1016/S0038-1098(85)80025-9.

- ↑ "Nanotechnology Timeline". National Nanotechnology Initiative.

- ↑ Reed MA, Randall JN, Aggarwal RJ, Matyi RJ, Moore TM, Wetsel AE (1988). "Observation of discrete electronic states in a zero-dimensional semiconductor nanostructure" (PDF). Phys Rev Lett 60 (6): 535–537. Bibcode:1988PhRvL..60..535R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.535. PMID 10038575.

- ↑ http://www.technologyreview.com/news/509801/quantum-dots-get-commercial-debut-in-more-colorful-sony-tvs/

- ↑ "Nanotechnology Information Center: Properties, Applications, Research, and Safety Guidelines". American Elements.

- ↑ Brandrup, J.; Immergut, E.H. (1966). Polymer Handbook (2 ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 240–246.

- ↑ Khare, Ankur, Wills, Andrew W., Ammerman, Lauren M., Noris, David J., and Aydil, Eray S. (2011). "Size control and quantum confinement in Cu2ZnSnS4 nanocrystals". Chem. Commun. 47 (42): 47. doi:10.1039/C1CC14687D.

- ↑ Greenemeier, L. (5 February 2008). "New Electronics Promise Wireless at Warp Speed". Scientific American.

- ↑ "SCIENCE WATCH; Tiny Lasers Break Speed Record". The New York Times. 31 December 1991.

- ↑ C. Delerue, M. Lannoo (2004). Nanostructures: Theory and Modelling. Springer. p. 47. ISBN 3-540-20694-9.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Zherebetskyy D., Scheele M., Zhang Y., Bronstein N., Thompson C., Britt D., Salmeron M., Alivisatos P., Wang L.W. Science 2014 June;344(6190):1380-4 (2014). "Hydroxylation of the surface of PbS nanocrystals passivated with oleic acid". Science 344 (6190): 1380–1384. doi:10.1126/science.1252727.

- ↑ Silbey, Robert J.; Alberty, Robert A.; Bawendi, Moungi G. (2005). Physical Chemistry, 4th ed. John Wiley &Sons. p. 835.

- ↑ Prati, Enrico; De Michielis, Marco; Belli, Matteo; Cocco, Simone; Fanciulli, Marco; Kotekar-Patil, Dharmraj; Ruoff, Matthias; Kern, Dieter P et al. (2012). "Few electron limit of n-type metal oxide semiconductor single electron transistors". Nanotechnology 23 (21): 215204. arXiv:1203.4811. Bibcode:2012Nanot..23u5204P. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/23/21/215204. PMID 22552118.

- ↑ Lee SW, Mao C, Flynn CE, Belcher AM (2002). "Ordering of quantum dots using genetically engineered viruses". Science 296 (5569): 892–5. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..892L. doi:10.1126/science.1068054. PMID 11988570.

- ↑ Whaley SR, English DS, Hu EL, Barbara PF, Belcher AM (2000). "Selection of peptides with semiconductor binding specificity for directed nanocrystal assembly". Nature 405 (6787): 665–8. doi:10.1038/35015043. PMID 10864319.

- ↑ Jawaid A.M., Chattopadhyay S., Wink D.J., Page L.E., Snee P.T. (2013). "A". ACS Nano 7: 3190–3197. doi:10.1021/nn305697q.

- ↑ http://www.azonano.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=3473

- ↑ Quantum Materials Corporation and the Access2Flow Consortium (2011). "Quantum materials corp achieves milestone in High Volume Production of Quantum Dots". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ↑ The Economist (16 June 2011). "Quantum-dot displays-Dotting the eyes". Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ↑ Hauser, Charlotte A. E.; Zhang, Shuguang (25 Nov 2010). "Peptides as biological semiconductors". Nature 468 (7323): 516–517. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..516H. doi:10.1038/468516a. Retrieved 10 Apr 2010.

- ↑ Van Driel, A. F. (2005). "Frequency-Dependent Spontaneous Emission Rate from CdSe and CdTe Nanocrystals: Influence of Dark States" (PDF). Physical Review Letters 95 (23): 236804. arXiv:cond-mat/0509565. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95w6804V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.236804. PMID 16384329.

- ↑ Leatherdale, C. A.; Woo, W. -K.; Mikulec, F. V.; Bawendi, M. G. (2002). "On the Absorption Cross Section of CdSe Nanocrystal Quantum Dots". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 106 (31): 7619. doi:10.1021/jp025698c.

- ↑ Achermann, M.; Petruska, M. A.; Smith, D. L.; Koleske, D. D.; Klimov, V. I. (2004). "Energy-transfer pumping of semiconductor nanocrystals using an epitaxial quantum well". Nature 429 (6992): 642–646. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..642A. doi:10.1038/nature02571.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Walling, M. A.; Novak, Shepard (February 2009). "Quantum Dots for Live Cell and In Vivo Imaging". Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10 (2): 441–491. doi:10.3390/ijms10020441. PMC 2660663. PMID 19333416.

- ↑ Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA et al. (2005). "Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics". Science 307 (5709): 538–44. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..538M. doi:10.1126/science.1104274. PMC 1201471. PMID 15681376.

- ↑ Marchuk, K., Guo, Y., Sun, W., Vela, J., & Fang, N. (2012). "High-precision tracking with non-blinking quantum dots resolves nanoscale vertical displacement". Journal of the American Chemical Society 134 (14): 6108–6111. doi:10.1021/ja301332t.

- ↑ Lane, L. A., Smith, A. M., Lian, T., & Nie, S. (2014). "Compact and Blinking-Suppressed Quantum Dots for Single-Particle Tracking in Live Cells". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 118 (49): 14140–14147. doi:10.1021/jp5064325.

- ↑ Spie (2014). "Paul Selvin Hot Topics presentation: New Small Quantum Dots for Neuroscience". SPIE Newsroom. doi:10.1117/2.3201403.17.

- ↑ Tokumasu, F; Fairhurst, Rm; Ostera, Gr; Brittain, Nj; Hwang, J; Wellems, Te; Dvorak, Ja (Mar 2005). "Band 3 modifications in Plasmodium falciparum-infected AA and CC erythrocytes assayed by autocorrelation analysis using quantum dots". Journal of Cell Science (Free full text) 118 (Pt 5): 1091–8. doi:10.1242/jcs.01662. PMID 15731014.

- ↑ Dahan, M; Lévi, S; Luccardini, C; Rostaing, P; Riveau, B; Triller, A (Oct 2003). "Diffusion dynamics of glycine receptors revealed by single-quantum dot tracking". Science 302 (5644): 442–5. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..442D. doi:10.1126/science.1088525. PMID 14564008.

- ↑ Howarth M, Liu W, Puthenveetil S, Zheng Y, Marshall LF, Schmidt MM, Wittrup KD, Bawendi MG, Ting AY. Nat Methods. 2008 May;5(5):397-9 (2008). "Monovalent, reduced-size quantum dots for imaging receptors on living cells". Nature methods 5 (5): 397–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1206. PMC 2637151. PMID 18425138.

- ↑ Akerman ME, Chan WC, Laakkonen P, Bhatia SN, Ruoslahti E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 1;99(20):12617-21 (2002). "Nanocrystal targeting in vivo". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (20): 12617–21. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9912617A. doi:10.1073/pnas.152463399. PMC 130509. PMID 12235356.

- ↑ Farlow J, Seo D, Broaders, KE, Taylor, MJ, Gartner ZJ, Jun, YW. Nat. Methods. U S A. 2013 Oct (2013). "Formation of targeted monovalent quantum dots by steric exclusion". Nature Methods 10: 1203–1205. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2682.

- ↑ Dwarakanath S, Bruno JG, Shastry A, Phillips T, John AA, Kumar A, Stephenson LD. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 Dec 17;325(3):739-43 (2004). "Quantum dot-antibody and aptamer conjugates shift fluorescence upon binding bacteria". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 325 (3): 739–43. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.099. PMID 15541352.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Ballou, B; Lagerholm, Bc; Ernst, La; Bruchez, Mp; Waggoner, As (2004). "Noninvasive imaging of quantum dots in mice". Bioconjugate chemistry (Free full text) 15 (1): 79–86. doi:10.1021/bc034153y. PMID 14733586.

- ↑ Resch-Genger, Ute; Grabolle, Markus; Cavaliere-Jaricot, Sara; Nitschke, Roland; Nann, Thomas (28 August 2008). "Quantum dots versus organic dyes as fluorescent labels". Nature Methods 5 (9): 763–775. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1248.

- ↑ Algar, W. Russ; Krull, Ulrich J. (7 November 2007). "Quantum dots as donors in fluorescence resonance energy transfer for the bioanalysis of nucleic acids, proteins, and other biological molecules". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 391 (5): 1609–1618. doi:10.1007/s00216-007-1703-3.

- ↑ Beane, Gary; Boldt, Klaus; Kirkwood, Nicholas; Mulvaney, Paul (7 August 2014). "Energy Transfer between Quantum Dots and Conjugated Dye Molecules". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 118 (31): 18079–18086. doi:10.1021/jp502033d.

- ↑ "Gene Silencer and Quantum Dots Reduce Protein Production to a Whisper". Newswise. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ↑ Pelley JL, Daar AS, Saner MA. Toxicol Sci. 2009 Dec;112(2):276-96 (2009). "State of academic knowledge on toxicity and biological fate of quantum dots". Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 112 (2): 276–96. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp188. PMC 2777075. PMID 19684286.

- ↑ Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Itty Ipe B, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Oct;25(10):1165–70. Epub 2007 Sep 23 (2007). "Renal clearance of quantum dots". Nature Biotechnology 25 (10): 1165–70. doi:10.1038/nbt1340. PMC 2702539. PMID 17891134.

- ↑ Armon Sharei, Janet Zoldan, Andrea Adamo, Woo Young Sim, Nahyun Cho, Emily Jackson, Shirley Mao, Sabine Schneider, Min-Joon Han, Abigail Lytton-Jean, Pamela A. Basto, Siddharth Jhunjhunwala, Jungmin Lee, Daniel A. Heller, Jeon Woong Kang, George C. Hartoularos, Kwang-Soo Kim, Daniel G. Anderson, Robert Langer, and Klavs F. Jensen (2013). "A vector-free microfluidic platform for intracellular delivery". PNAS 110: 2082–7. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.2082S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218705110. PMC 3568376. PMID 23341631.

- ↑ Schaller, R.; Klimov, V. (2004). "High Efficiency Carrier Multiplication in PbSe Nanocrystals: Implications for Solar Energy Conversion". Physical Review Letters 92 (18): 186601. arXiv:cond-mat/0404368. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92r6601S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.186601. PMID 15169518.

- ↑ "Nano LEDs printed on silicon". 3 July 2009.

- ↑ Hoshino, Kazunori; Gopal, Ashwini; Glaz, Micah S.; Vanden Bout, David A.; Zhang, Xiaojing (2012). "Nanoscale fluorescence imaging with quantum dot near-field electroluminescence". Applied Physics Letters 101 (4): 043118. Bibcode:2012ApPhL.101d3118H. doi:10.1063/1.4739235.

- ↑ Shrinking quantum dots to produce white light. Vanderbilt's Online Research Magazine. Vanderbilt.edu. Retrieved on 24 July 2013.

- ↑ Konstantatos, G.; Sargent, E. H. (2009). "Solution-Processed Quantum Dot Photodetectors". Proceedings of the IEEE 97 (10): 1666–1683. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2009.2025612.

- ↑ Vaillancourt, J.; Lu, X.-J.; Lu, Xuejun (2011). "A High Operating Temperature (HOT) Middle Wave Infrared (MWIR) Quantum-Dot Photodetector". Optics and Photonics Letters 4 (2): 1–5. doi:10.1142/S1793528811000196.

- ↑ Zumbühl DM, Miller JB, Marcus CM, Campman K, Gossard AC (December 2002). "Spin-orbit coupling, antilocalization, and parallel magnetic fields in quantum dots". Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 (27): 276803. arXiv:cond-mat/0208436. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..89A6803Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.276803. PMID 12513231.

- ↑ G. J. Iafrate, K. Hess, J. B. Krieger, and M. Macucci (1995). "Capacitive nature of atomic-sized structures". Phys. Rev. B 52 (15): 10737–10739. doi:10.1103/physrevb.52.10737.

- ↑ J.J. Thomson (1904). "On the Structure of the Atom: an Investigation of the Stability and Periods of Oscillation of a number of Corpuscles arranged at equal intervals around the Circumference of a Circle; with Application of the Results to the Theory of Atomic Structure" (EXTRACT OF PAPER). Philosophical Magazine Series 6 7 (39): 237–265. doi:10.1080/14786440409463107.

- ↑ S. Bednarek, B. Szafran, and J. Adamowski (1999). "Many-electron artificial atoms". Phys. Rev. B 59 (20): 13036–13042. Bibcode:1999PhRvB..5913036B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.59.13036.

- ↑ V. M. Bedanov and F. M. Peeters (1994). "Ordering and phase transitions of charged particles in a classical finite two-dimensional system". Physical Review B 49: 2667–2676. Bibcode:1994PhRvB..49.2667B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.49.2667.

- ↑ T. LaFave Jr. (2013). "Correspondences between the classical electrostatic Thomson Problem and atomic electronic structure". Journal of Electrostatics 71 (6): 1029–1035. doi:10.1016/j.elstat.2013.10.001.

- ↑ T. LaFave Jr. (2011). "The discrete charge dielectric model of electrostatic energy". Journal of Electrostatics 69 (5): 414–418. doi:10.1016/j.elstat.2013.10.001.

External links

- Quantum Dots: Technical Status and Market Prospects

- Quantum dots that produce white light could be the light bulb's successor

- Single quantum dots optical properties

- Quantum dot on arxiv.org

- Quantum Dots Research and Technical Data