Q-Vectors

Q-vectors are used in atmospheric dynamics to understand physical processes such as vertical motion and frontogenesis. Q-vectors are not physical quantities that can be measured in the atmosphere but are derived from the quasi-geostrophic equations and can be used in the previous diagnostic situations. On meteorological charts, Q-vectors point toward upward motion and away from downward motion. Q-vectors are an alternative to the omega equation for diagnosing vertical motion in the quasi-geostrophic equations.

Derivation

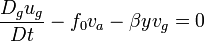

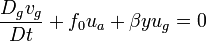

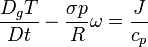

First derived in 1978,[1] Q-vector derivation can be simplified for the midlatitudes, using the midlatitude β-plane quasi-geostrophic prediction equations:[2]

-

(x component of quasi-geostrophic momentum equation)

(x component of quasi-geostrophic momentum equation) -

(y component of quasi-geostrophic momentum equation)

(y component of quasi-geostrophic momentum equation) -

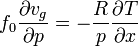

(quasi-geostrophic thermodynamic equation)

(quasi-geostrophic thermodynamic equation)

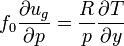

And the thermal wind equations:

(x component of thermal wind equation)

(x component of thermal wind equation)

(y component of thermal wind equation)

(y component of thermal wind equation)

where  is the Coriolis parameter, approximated by the constant 1e−4 s−1;

is the Coriolis parameter, approximated by the constant 1e−4 s−1;  is the atmospheric ideal gas constant;

is the atmospheric ideal gas constant;  is the latitudinal change in the Coriolis parameter

is the latitudinal change in the Coriolis parameter  ;

;  is a static stability parameter;

is a static stability parameter;  is the specific heat at constant pressure;

is the specific heat at constant pressure;  is pressure;

is pressure;  is temperature; anything with a subscript

is temperature; anything with a subscript  indicates geostrophic; anything with a subscript

indicates geostrophic; anything with a subscript  indicates ageostrophic;

indicates ageostrophic;  is a diabatic heating rate; and

is a diabatic heating rate; and  is the Lagrangian rate change of pressure with time.

is the Lagrangian rate change of pressure with time.  . Note that because pressure decreases with height in the atmosphere, a

. Note that because pressure decreases with height in the atmosphere, a  is upward vertical motion, analogous to

is upward vertical motion, analogous to  .

.

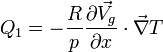

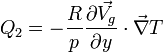

From these equations we can get expressions for the Q-vector:

![Q_1 = - \frac{R}{p} \left[ \frac{\partial u_g}{\partial x} \frac{\partial T}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial v_g}{\partial x} \frac{\partial T}{\partial y} \right]](../I/m/78cbbf407ed7f140ac2a8d68e4296236.png)

![Q_2 = - \frac{R}{p} \left[ \frac{\partial u_g}{\partial y} \frac{\partial T}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial v_g}{\partial y} \frac{\partial T}{\partial y} \right]](../I/m/94b784af0f261b64175ad71de5dcdca6.png)

And in vector form:

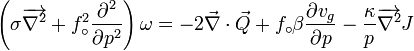

Plugging these Q-vector equations into the quasi-geostrophic omega equation gives:

Which in an adiabatic setting gives:

Expanding the left-hand side of the quasi-geostrophic omega equation in a Fourier Series gives the  above, implying that a

above, implying that a  relationship with the right-hand side of the quasi-geostrophic omega equation can be assumed.

relationship with the right-hand side of the quasi-geostrophic omega equation can be assumed.

This expression shows that the divergence of the Q-vector ( ) is associated with downward motion. Therefore, convergent

) is associated with downward motion. Therefore, convergent  forces ascend and divergent

forces ascend and divergent  forces descend.[3] Q-vectors and all ageostrophic flow exist to preserve thermal wind balance. Therefore, low level Q-vectors tend to point in the direction of low-level ageostrophic winds.[4]

forces descend.[3] Q-vectors and all ageostrophic flow exist to preserve thermal wind balance. Therefore, low level Q-vectors tend to point in the direction of low-level ageostrophic winds.[4]

Applications

Q-vectors can be determined wholly with: geopotential height ( ) and temperature on a constant pressure surface. Q-vectors always point in the direction of ascending air. For an idealized cyclone and anticyclone in the Northern Hemisphere (where

) and temperature on a constant pressure surface. Q-vectors always point in the direction of ascending air. For an idealized cyclone and anticyclone in the Northern Hemisphere (where  ), cyclones have Q-vectors which point parallel to the thermal wind and anticyclones have Q-vectors that point antiparallel to the thermal wind.[5] This means upward motion in the area of warm air advection and downward motion in the area of cold air advection.

), cyclones have Q-vectors which point parallel to the thermal wind and anticyclones have Q-vectors that point antiparallel to the thermal wind.[5] This means upward motion in the area of warm air advection and downward motion in the area of cold air advection.

In frontogenesis, temperature gradients need to tighten for initiation. For those situations Q-vectors point toward ascending air and the tightening thermal gradients.[6] In areas of convergent Q-vectors, cyclonic vorticity is created, and in divergent areas, anticyclonic vorticity is created.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hoskins, B. J.; I. Draghici and H. C. Davies (1978). "A new look at the ω-equation". Quart. J. R. Met. Soc 104: 31–38.

- ↑ Holton, James R. (2004). An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. New York: Elsevier Academic. pp. 168–72. ISBN 0-12-354015-1.

- ↑ Holton, James R. (2004). An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. New York: Elsevier Academic. p. 170. ISBN 0-12-354015-1.

- ↑ Hewitt, C. N. (2003). Handbook of atmospheric science: principles and applications. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 286. ISBN 0-632-05286-4.

- ↑ Holton, James R. (2004). An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. New York: Elsevier Academic. p. 171. ISBN 0-12-354015-1.

- ↑ National Weather Service, Jet Stream - Online School for Weather. "Glossary: Q's". NOAA - NWS. Retrieved 15 March 2012.