Pyramid of Sahure

| Pyramid of Sahure | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sahure's pyramid as seen from the causeway. | ||||||||||||||

| Sahure, 5th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 29°53′52″N 31°12′12″E / 29.89778°N 31.20333°ECoordinates: 29°53′52″N 31°12′12″E / 29.89778°N 31.20333°E | |||||||||||||

| Ancient name |

Ḫˁj-b3 S3ḥ.w Rˁ Khai ba Sahura The Rising of the Ba Spirit of Sahure[1] | |||||||||||||

| Constructed | c. 2480 BC | |||||||||||||

| Type | True (now ruined) | |||||||||||||

| Material | Limestone | |||||||||||||

| Height | 47 m (154 ft) | |||||||||||||

| Base | 78.75 m (258.4 ft) | |||||||||||||

| Volume | 96,542 m3 (126,272 cu yd) | |||||||||||||

| Slope | 50°11' | |||||||||||||

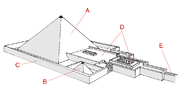

The Pyramid of Sahure was the first pyramid built in the necropolis of Abusir, Egypt. The pyramid was constructed for the burial of Sahure, second pharaoh of the fifth dynasty c. 2480 BC.[1] Sahure's pyramid is part of a larger mortuary complex comprising a temple on the shores of Abusir lake, a causeway from this temple to the high temple located against the main pyramid and a separate cult pyramid for the Ka of the king.[2] The complex was known in ancient Egyptian as Ḫˁj-b3 S3ḥ.w Rˁ, "The Rising of the Ba Spirit of Sahure".[1]

The pyramid complex of Sahure was extensively excavated at the beginning of the 20th century by Ludwig Borchardt and is now recognized as a milestone in ancient Egyptian tomb architecture, its layout defining a standard that would remain unchanged until the end of the 6th dynasty some 300 years later.[1][3] The valley and high temples as well as the causeway of the complex were richly decorated with over 10,000 sq. m (107,640 sq. ft) of fine reliefs that made the complex renowned in antiquity. The high temple is also remarkable for the variety of building materials used for its construction, from the alabaster and basalt floors to the fine limestone and red granite of the walls.[1][2][4]

Discovery and excavations

The first investigations of the pyramid of Sahure were undertaken in the mid 19th century by John Shae Perring and Karl Richard Lepsius who included the pyramid in his list under the number XXVIII. These investigations remained superficial however and no serious excavations of the pyramid took place at the time, due mainly to its state of ruin. The pyramid was entered for the first time a few years later by Jacques de Morgan but he too did not explore it further.[5]

Realizing the significance of the pyramid, the egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt undertook extensive excavations of the site between 1902 and 1908, exploring the entire mortuary complex. He published his discoveries in a two-volume study Das Grabdenkmal des Konigs Sahure, "The Funerary Monument of King Sahure", which is still considered the standard work on Sahure's complex.[3]

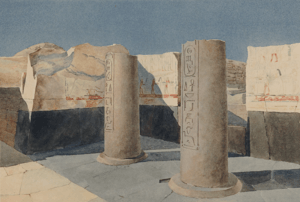

During the excavations, Borchardt discovered the still largely intact architrave of the high temple as well as a group of palmiform columns. He sent some of these columns for exhibition in Germany as was customary at the time, while the rest stayed in Egypt. The columns sent to Germany were to be displayed in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. However, because of lack of space the columns and other findings from Borchardt's excavations were not displayed before the 1980s, when they were showcased for the first time in the old stables of the Charlottenburg Palace. More recently these were moved to the Pergamon Museum. Borchardt's work was very thorough and a further survey undertaken by Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi in the early 1960s yielded no fundamentally new results.[5]

In 1994 the pyramid of Sahure was the object of restoration works in preparation of the opening of Abusir to tourists. Surprisingly, these works quickly revealed large decorated blocks buried in the sand.[6] A subsequent excavation led by Zahi Hawass and Tarek el-Awady unearthed 13 finely carved limestone slabs with iconographically and artistically unique reliefs[5] from the upper part of the causeway, an area which had not been investigated in detail by Borchardt. [2][4]

Location

Sahure preferred the site of Abusir for the construction of his mortuary complex to the heavily built necropolis of Saqqara. In doing so he might have been influenced by the presence of Userkaf's sun temple, located about 400 m (1,300 ft) to the southeast of the rocky promontory on which Sahure's pyramid stands.

Two other factors that may have contributed to the decision are:

- The proximity of the Abusir lake which made the complex easily accessible for the funerary cult of the king.[7]

- The proximity of Memphis the capital and seat of power at the time. In particular, Sahure's palace Wetjes neferu Sahure, "Sahure's splendor soars up to heaven", might have been located in the vicinity of Abusir.[5]

Regardless of Sahure's motivations, the construction of his complex marks the birth of the necropolis of Abusir which would serve at least until the Saite period some 2000 years later.

The pyramid of Sahure is smaller than Userkaf's and stood less than one third the height of the great pyramid at the time of its completion. In the mean time a comparatively greater emphasis was put on the construction of the mortuary temple and its decoration.[1] The pyramid complex was completed during Sahure's lifetime as witnessed by reliefs of the causeway discovered in 1994 and showing the ritual celebrations accompanying the completion of the pyramid.[8]

Mortuary complex

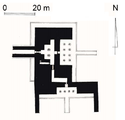

Sahure's mortuary complex is oriented on an east-west axis and comprises all the standard elements of a mortuary complex: a valley temple located on the shores of the Abusir lake linked to the main enclosure via a long causeway and, within the enclosure wall, the main pyramid, the high temple and a smaller cult pyramid.[1][4]

Remarkable is the absence of peripheral burials for the members of the royal family. Indeed, no mastaba or pyramid of a queen dating to Sahure's time has been discovered as of 2012 in the immediate vicinity of Sahure's pyramid. This is in rupture with a tradition dating back at least to pharaoh Sneferu and that would be followed by Sahure's successors. Consequently, Sahure's consort queen Meretnebty, is only attested through carved reliefs found in the high temple.[9] The reason for this absence is unknown.

The complex also lacks a northern chapel located close to the main pyramid entrance. However this type of structure was unknown at the time of Borchardt's excavations and any existing sparse remnants may thus have remained undetected.

Valley temple

Sahure's valley temple was located on the shores of Abusir lake. It was rectangular in plan, being 32 m (105 ft) long and 24 m (79 ft) wide, and oriented on a north-south axis. The base of walls of the temple were carved with concave molding and the corners of the temple were rounded. The valley temple is now in ruins and partly obscured as it has been buried over time by up to 5 m (16 ft) of sludge deposits from the lake. It is nonetheless considered the best preserved valley temple of Egypt after that of Khafre.[1][2][4]

The main entrance to the valley temple was, as usual, located on the eastern side. It comprised a ramp directly in front of a portico with two rows of four palmiform columns made of red granite. Less common was the presence of a second entrance on the southern side of the temple, apparently built after the main entrance during a second phase of construction. The southern entrance was accessible via a canal[1] and comprised a ramp and a portico with four columns. These were simple conical pillars without capital. Borchardt proposed that this entrance was reserved to the priests.[3] Finally, a wall there suggests the presence of the pyramid town The Soul of Sahure Comes Forth in Glory[1] in the close vicinity of the valley temple.

In the center of the temple was a small T-shaped hall with two columns. The hall comprised a staircase access to a roof terrace and led westward to the causeway. The floor of the hall was paved with black basalt, its ceiling was decorated with star patterns, and the limestone walls were adorned by a pink granite dado and, above, by painted reliefs depicting the king hunting.[10]

-

Plan of Sahure's valley temple.

-

Borchardt's reconstruction of Sahure's valley temple (1910).

-

Model of the valley temple, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Causeway

A 235-metre-long (771 ft) causeway connected the valley temple of Sahure's pyramid complex to the high temple. The causeway was roofed, its side walls, ceiling and flooring being made of limestone slabs, some of which are still visible today. In between the ceiling slabs were narrow slits allowing natural light to penetrate the ensemble. The walls of the causeway were covered with painted reliefs throughout, some of which were discovered during the excavations started in the mid-1990s of the upper part of the causeway. These include representations of the king as a Sphinx trampling over his enemies,[2][4][10] a procession of enemies being led by gods, depictions of the bringing of the pyramidion to the main pyramid and of the ceremonies following the completion of the complex.

Among the reliefs recently discovered, one showed the king with his royal entourage in the garden of his palace Wetjes neferu Sahure. There, next to a personage named Ranefer, the text Neferirkare, King of Upper and Lower Egypt had been added.[11] Thanks to this inscription, egyptologists such as Miroslav Verner and Tarek el-Awady now believe that Neferirkare Kakai was the eldest son of Sahure and bore the name Ranefer before his accession to the throne.[6][11] Alternatively, Neferirkare Kakai could be a brother of Sahure, in which case he may have usurped the throne at the expense of his nephew, Netjerirenre.[12]

Another important limestone block shows Sahure cultivating a Myrrh tree in what is probably the garden of his palace.[13] The same block also shows four ships coming back from an expedition to Punt, loaded with Myrrh trees, people from Punt as well as dogs and donkeys.[13][14] Finally, a relief showing starving Bedouins was unearthed, which is very similar to the one from the pyramid of Unas.[5] This discovery is significant as Unas' relief was thought to be the unique witness of a real event: the declining quality of life of Saharan Bedouins brought about by the end of the Sahara wet phase[5] c. 2350 BC, when it has in fact a mostly symbolic value.

-

The ruined causeway of Sahure's pyramid complex

-

The end of the causeway, close to the high temple

-

Relief from the causeway depicting Sahure as a Sphinx

-

Starving Bedouins from the pyramid of Unas

High temple

Sahure's mortuary temple represents the definitive prototype for all later pyramid temples of the second half of the Old Kingdom. For the first time, the funerary and sacrificial temple are no longer separated but rather integrated together in a continuous east-west arrangement within the complex. The ensemble was built of and clad with fine Tura limestone and extensively decorated and worked throughout. Here again, the base of walls were carved with concave molding and the corners of the temple were rounded.

The temple was accessed from the eastern side by a causeway that led to a 21-metre-long (69 ft) entrance hall. This hall had a nearly 7-metre-high (23 ft) stone barrel vault, a limestone flooring and a pink granite dado. The walls were covered with extensive painted reliefs.[10] In ancient times, the entrance hall was known as pr-wrw, "House of the Great Ones".[15] Borchardt believed this hall served as the final station for the funeral procession of the king before the burial proper.[2]

From the hall, a large granite door led to an open courtyard, which was lined with 16 monolithic pink granite columns supporting a monumental granite architrave. These columns were carved so as to resemble the trunk and crown of a palm tree, which was regarded as a fertility and eternity symbol. According to Herbert Ricke, these columns represent the sacred palm grove of Buto. Here again, Sahure's temple served as an example for his successors: plantiform columns became the standard for columns of pyramid temples throughout the second half of the Old Kingdom. The columns all bore the names and title of Sahure as well as representations of the snake goddess Wadjet symbolizing Lower Egypt in the northern part of the courtyard and the vulture of Nekhbet, goddess of Upper Egypt, in the southern half. The granite architrave was inscribed with the complete royal titulary of Sahure and supported limestone ceiling slabs decorated with stars on a blue background.[1]

The walls of the courtyard, made of Tura limestone, were adorned with fine reliefs showing Sahure's victories against Asiatics and Libyans, as well as prisoners and other spoils from the battles.[10] The courtyard was paved with irregularly shaped but polished black basalt slabs, some of which are still visible today.[16] In the northwest corner was an alabaster altar decorated with the symbols of Egyptian unification and scenes of offerings made to Sahure. Finally, the courtyard may have housed life-size statues of the king between the columns. The courtyard was surrounded by a corridor whose walls were covered with painted reliefs. These represented Sahure hunting, fowling and fishing in presence of his courtiers, thereby demonstrating the king's control over nature, one of his sacral duties. Finally, a relief found in the ruins of the courtyard depicts Syrian brown bears.

-

Remnants of the massive granite architrave inscribed with Sahure's titles.

-

Palmiform column from the open courtyard.

-

The ruins of the courtyard.

-

A relief depicting defeated enemies from the walls of the courtyard.

The western end of the courtyard leads to a transverse corridor that separated the public from the sacred part of the temple only accessible to the priests. The decoration of this corridor was similar to that of the courtyard with a black basalt flooring, granite dado and decorated limestone walls. The few surviving fragments of the reliefs from the east wall show ships coming back from a naval expedition to Syria.[1] The transverse corridor served as an access to various parts of the inner temple. In its center part was an alabaster staircase on both sides of which were two papyriform columns set into deep niches.[1] The columns supported a granite architrave which fell victim to stone robbers and can now be found in the oil press of St. Jeremiah monastery in Saqqara.[17] Both of these deep niches were decorated with reliefs depicting offering bearers and led to two-story galleries of magazine rooms. The gallery accessible from the northern niche consisted of 10 rooms which housed the cultic objects used for the rituals carried out in the mortuary temple. The southern gallery comprised 17 rooms, which probably served as storage rooms for the offerings. Each magazine room contained a staircase to the second floor, some stairways being carved directly into the masonry of the wall.[3]

At the northern end of the transverse corridor were a few more chambers and a passageway to the court surrounding the main pyramid. In addition, there was a stairway to the roof terrace of the temple. The southern end of the transverse corridor similarly led to a few chambers, which in turn led to the main pyramid as well as to the small courtyard of the cult pyramid. There lay a small portico in the enclosure wall with two inscribed granite columns. This portico served as a service entrance to the pyramid complex for the deliveries of goods to the magazine rooms.[1] At the center of the transverse corridor, the staircase led to a chapel with five niches. This chapel had an alabaster floor, a dado of pink granite and splendidly decorated limestone walls, with the exception of the niches in the west wall and the dado. The ceiling was adorned with stars. The niches housed cult statues of the king, none of which has survived to this day.

-

Relief from the transverse corridor depicting the return of a naval expedition from Syria.

-

Return of a naval expedition from Syria.

-

Granite column of the side entrance.

-

A ceiling slab decorated with stars.

At the southern end of the five niches chapel, a passage led to two elongated antechambers and finally to the offering chapel. There took place the sacrificial offerings for the king after his death. The offering chapel was directly adjoining the main pyramid eastern side as was customary. The focus of the chapel was a false door, a roughly worked granite slab that would have given Sahure's spirit access to the food offerings made for him according to ancient Egyptian beliefs. Unusually, this false door was uninscribed when it should have borne the name and titles of Sahure as well as magical spells. This observation led Borchardt to propose that the granite slab was once covered by a copper or golden panel bearing the necessary inscriptions,[3] of which no trace remains today. The offering chapel had an alabaster flooring and a vaulted limestone ceiling with star decorations. It housed a black granite statue of the king.[1] There was also a basin for collecting liquids which had an outflow of copper tubing. This was connected to a vast drainage system made of copper pipes laid under the pavement of the temple and leading to a central, limestone-lined, wastewater channel. Overall, the drainage system comprised approximately 380 m (1,250 ft) of copper piping. The basin was sealed with lead plugs.[2][18]

Immediately to the north of the offering chapel, a granite doorway led to five more chambers, which probably served to prepare the food offerings. In two of these were further basins connected to the drainage system via copper pipes.[1][2][4]

Cult pyramid

The southeastern part of Sahure's pyramid complex was occupied by a small cult pyramid, with its own enclosure wall and courtyard. Cult pyramids were erected during the Old Kingdom as tombs for the Ka of the deceased ruler. The pyramid originally stood 11.55 m (37.9 ft) high with a base of 15.7 m (52 ft) and a slope of 56°. Its inner core comprised two steps of roughly hewn limestone blocks clad with fine Tura limestone. This construction technique, with a low-quality core masonry, meant a considerable saving of labor at the time of the construction. However, as the outer casing of pyramid fell victim to stone robbers throughout the millennia, the loosely assembled core material was progressively exposed and fared much worse over time than that of the 4th dynasty pyramids. Thus, today the cult pyramid is ruined beyond recognition.

The pyramid courtyard was accessed either from the transverse corridor or through the side entrance of the mortuary temple via a portico with two round columns bearing Sahure's name and titles. No building seems to have stood in this courtyard. At the base of northern side of the pyramid was a passage leading to a T-shaped underground chamber, oriented on an east-west axis and under the tip of the pyramid. No artifacts were found onsite during the excavation of this chamber which might have housed a statue of Sahure's Ka.[2][4]

Main pyramid

Construction

The base of the pyramid has been heavily damaged through stone robbing and the dimensions of the pyramid are difficult to ascert with certainty. According to Borchardt,[3] Sahure's pyramid originally reached an height of 90 royal cubits making it 47 m (154 ft) high with a base of 150 royal cubit, 78.75 m (258.4 ft), and a slope of 50°11'. The architects of the pyramid made a sizeable error when delimiting the base: the southeast corner of the pyramid is 1.58 m (5.2 ft) too far to the east. The pyramid is consequently distorted, although much of the distortion, being on the eastern side, is concealed by the adjacent mortuary temple.[2][4]

Unlike the pyramids of the 4th dynasty, the pyramids of the 5th dynasty were not built on the local bedrock but rather on a foundation made of two thick layers of limestone blocks. Although the foundation of Sahure's pyramid is not accessible and has thus not been examined, archaeologists believe that it was constructed according to the same technique.[2][4] The pyramid core masonry consists of low-grade roughly hewn limestone blocks from local quarries. The spaces between the blocks were filled with rubble and mortar. The blocks were laid in horizontal layers constituting 6 steps which then received the white limestone cladding. Just as for the cult pyramid, this construction technique is responsible for the current ruined state of the pyramid.[2][4]

The substructures of the pyramid were built in a T-shaped open ditch reaching to the foundation layer and left open to allow for simultaneous works on the pyramid foundation and core. The ditch comprised a gap in the pyramid side wall which was eventually filled with rubble and is still recognizable today. This construction technique is common to all pyramids of the 5th dynasty and can directly be seen in the case of the Pyramid of Neferefre, which was left unfinished.

-

Unfinished Pyramid of Neferefre, showing the T-shaped ditch construction technique.

-

Model of Sahure's pyramid complex, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

The ruined pyramid as seen from the open courtyard of the high temple.

Substructures

The substructure of Sahure's pyramid was built in a shallow T-shaped open ditch (see above). The ditch was so shallow that the corridor leading from the pyramid entrance to the grave chamber is horizontal overall and, in parts, slightly ascending into the pyramid core.

The entrance to the pyramid is located at ground level in the middle of the base of the north side. The entrance gives access to a 4.25 m (13.9 ft) long descending passageway with a slope 24° 48', a width of 1.27 m (4.2 ft) and a height 1.87 m (6.1 ft). This passageway is lined with red granite and leads to a small vestibule lined with fine limestone. At this point intruders would have encountered a red granite portcullis blocking the way to the burial chamber. Beyond this portcullis, is a slightly ascending 22.3 m (73 ft) long corridor with a slope of 5°. The last 3 m (9.8 ft) of the corridor are horizontal and lead to the granite-paneled door of the burial chamber, located under the tip of the pyramid.

Sahure's burial chamber is oriented on an east-west axis and is today severely damaged. The chamber was so heavily robbed of its stones that it is not even clear if it comprised one or two rooms, an antechamber and the burial chamber, as was customary during the 5th dynasty. Supposing that the chamber(s) must have had round integer dimensions in royal cubits, archaeologists proposed that it was 6 royal cubits i.e. 3.15 m (10.3 ft) large and 24 royal cubits long, 12.6 m (41 ft).[4] These values remain speculative given the extensively ruined state of the chamber. The gabled ceiling of the chamber was made of colossal blocks of fine limestone disposed in three layers. The largest blocks of the top layer were almost 10 m (33 ft) long and 4 m (13 ft) thick. Today all the ceiling blocks are broken, contributing to the overall instability of the pyramid. The last archaeologists who excavated the burial chamber in the 1960s, Maragioglio and Rinaldi, refrained from speaking there from fear that it would provoke the collapse of the ceiling.[5] Among the rubble of the chamber, John Shae Perring found fragments of a basalt sarcophagus.[1] No other artefacts from the original burial were found.[2][4]

Later uses

The courtyard of Sahure's mortuary temple became the center of a cult of the goddess Sekhmet from the 18th dynasty onwards. This choice of location may be linked with the extensive fine reliefs of the goddess carved on the walls of the courtyard.[2] At the beginning of the Christian era, the temple became a Coptic church.[19]

See also

- Fifth Dynasty of Egypt

- Egyptian pyramids

- Egyptian pyramid construction techniques

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- Lepsius list of pyramids

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Mark Lehner: The Complete Pyramids. (London:Thames and Hudson Ltd.) ISBN 0-500-05084-8

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Miroslav Verner, Steven Rendall: The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments, p. 313–324 ISBN 0-8021-1703-1

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Ludwig Borchardt: Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahurā. 2 Bände, J. C. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1910–1913 (Publication of Borchardt's excavations). Copyright-free online version

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 Rainer Stadelmann: Die agyptischen Pyramiden: Vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder (Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt), p. 164–174

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Miroslav Verner: Abusir - The realm of Osiris, American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-424-723-X, 2003, Google books

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 New Archaeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field - by Miroslav Verner: Sahure's Causeway (2007)

- ↑ Ancient Egypt website

- ↑ Zahi Hawass, Miroslav Verner: Newly Discovered Blocks from the Causeway of Sahure (Archaeological Report). In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. (MDIAK) vol. 51, von Zabern, Wiesbaden 1995, S. 177–186.

- ↑ Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. p. 54 ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Drawings of reliefs from Sahure's pyramid complex by Ludwig Borchardt: Das Grabdenkmal des Königs S'aḥu-Re (Band 2): Die Wandbilder: Abbildungsblätter, Online version

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Tarek el-Awady: The royal family of Sahure, new evidence in: M.Barta; F. Coppens, J. Krjci: Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-7308-116-4, p. 192–198

- ↑ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004), ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Tarek el-Awady: King Sahure with the Precious Trees from Punt in a Unique Scene, in: Proceeding of “Art and Architecture of the Old Kingdom”, Prague 2007.

- ↑ Tarek el-Awady: The Royal Navigation Fleet of Sahure, in: Study in Honor of Tohfa Handousa, ASAE (2007).

- ↑ Dieter Arnold: Per-weru p. 174 in The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture, Princeton University Press (2003), ISBN 0-691-11488-9, Google books

- ↑ See for example this picture

- ↑ The monastery on Touregypt

- ↑ Peter Jánosi: Die Pyramiden: Mythos und Archäologie p. 80–83, C. H. Beck, ISBN 3-406-50831-6.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Die Pyramide des Sahure, in: Die Pyramiden, pp.313−324.

Further reading

- Miroslav Verner: Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir, Netherlands Institute for the Near East, ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4, 1994.

- Richard H. Wilkinson: The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-05100-3, 2000.

- Miroslav Verner: Abusir - The realm of Osiris, American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-424-723-X, 2003, Google books.

- Zahi Hawass, Miroslav Verner: Newly Discovered Blocks from the Causeway of Sahure (Archaeological Report). In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. (MDIAK) vol. 51, von Zabern, Wiesbaden 1995, S. 177–186.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Sahure. |

- Egyptian Monuments: pyramid of Sahure at Abusir

- Ancient Egypt Website: The Pyramid of Sahure

- Video: entering the pyramid of Sahure

- Syrian brown bear relief fragment

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||