Pyramid of Neferefre

| Pyramid of Neferefre | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Neferefre | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 29°33′36.036″N 31°13′15.402″E / 29.56001000°N 31.22094500°E | ||||||||||||||

| Ancient name |

Nṯr.j-b3w-Rˁ-nfr=f Netjeri-bau-Ra-nefer-ef Divine is Neferefre's Power | ||||||||||||||

| Constructed |

Fifth Dynasty (2460 – 2455 BC)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Type |

True pyramid later reconstructed into a mastaba | ||||||||||||||

| Material | Limestone | ||||||||||||||

| Height | 7 metres (23 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Base | 65 metres (213 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Slope | 78° (after Mastaba rebuild) | ||||||||||||||

The Pyramid of Neferefre, also known as the Pyramid of Raneferef, is an unfinished Egyptian pyramid from the 5th Dynasty, located in the necropolis of Abusir, Egypt. After the early death of Pharaoh Neferefre, the unfinished building was reconstructed into a geometric mastaba, becoming the burial place of the deceased king. Despite the demolition of the actual pyramid, the complex was augmented through extensive construction of temples by Raneferef's successors.[2][3]

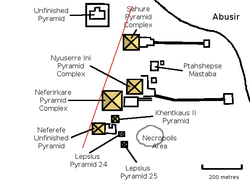

The pyramid was initially ignored by egyptologists. The first assignment was made by Karl Richard Lepsius, who called it Lepsius XXVI, but a definitive research was established in 1974 by the Czech team of Charles University in Prague under Miroslav Verner. Items as papyri and statues were discovered consisting of important information about the short-ruling Neferefre. Known as nTri bAw nfrf ra ("Divine is Neferefre's Power"), the complex is located directly south-west of the Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai and west of the Pyramid of Khentkaus II, and situated at the southern end of the necropolis, becoming the farthest into the desert of all pyramids of Abusir. With a base length of 65 metres (213 ft) it could have been the second-smallest king pyramid in the Old Kingdom of Egypt after the Pyramid of Unas. Apart from the actual pyramid, the complex includes the mortuary temple, the "Sanctuary of the Knife" and the sun sanctuary. The complex is surrounded by a large circular wall.

Exploration

The building was first noticed during the early archaeological studies of the necropolis of Abusir, but was not examined intensively. John Shae Perring (1837–1839) as well as later Karl Richard Lepsius (1842–1846), Jacques de Morgan (1890s) and Ludwig Borchardt (early 20th century) gave minimal attention to the building. Lepsius categorized the ruins under the name of Lepsius XXVI in his pyramid list.

A definitive assignment of the pyramid stump was at that time not possible. Some researchers attributed it to Raneferef, others to Shepseskare Isi, and others left the question of the authorship open. At that time it was unanimously decided that the early demolition excluded the theory of a funeral and consequently a mortuary cult.[4]

An intensive research of the remains began in 1974, by the Czech team of Charles University in Prague. These studies, headed by Miroslav Verner, brought a variety of insights. The most important was the fact that the unfinished pyramid served as the king's tomb, which was proven especially through the discovery of mummy remnants. Papyri were found in the ruins of the funerary temple in the temple archives as well as statues depicting the pharaoh, a proof that the building was definitely owned by Raneferef.[5] The study of the ruins offered a deeper insight to the engineering of pyramids in the 5th Dynasty, as the whole core masonry of the first steps was visible. This debunked Lepsius' and Borchardt's suggested theory of a structure of the slightly inward-inclined bowls with horizontal masonry.[2]

Building conditions

Raneferef began his short rule with the construction of the pyramid complex, the nTri bAw nfrf ra (Divine is Neferefre's Power), in the necropolis of Abusir, directly south-west of the Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai and west of the pyramid of Khentkaus II. The pyramid is situated at the southern end of the necropolis and is the farthest into the desert of all pyramids of Abusir.

The location was chosen to satisfy the alignment of the north-west corner of the three oldest king pyramids in this area – the Pyramid of Raneferef, the Pyramid of Neferirkare and the Pyramid of Sahure − on the same line, which possibly referred to the obelisk of the sun sanctuary in Heliopolis.[6] A similar orientation towards Heliopolis existed at the southern corners of the Giza Necropolis.[7]

The premature death of the king after a reign of only five years (from 2460 to 2455 BC)[1] led to the demolition of the construction works and to hasty conversion of the complex into a burial and cult ground in the shape of a square mastaba. His successors completed the cult places and the complex, but not the pyramid. According to papyri in the temple, the pyramid is a "hill".[8]

Plunderings and stone robberies

The building was looted and experienced stone robberies, common for pyramid complexes. The unfinished form with the flat roof offered looters a simple entry, as they could dig into the substructure from the easily accessible deck. The stone robbery and the lootings were apparently professionally organized, as residues were found in a workshop in the pyramid corpus. Looting possibly began in the First Intermediate Period and the stone robbery followed in the late New Kingdom, the Late Period, the reign by the Roman Empire and the Arabic Middle Ages right through the 19th century. Materials stolen from the pyramid complex could be found in nearby shaft tombs.[2] The temple area remained comparatively unaffected, as it was mainly composed of less valuable adobes.[3]

Pyramid

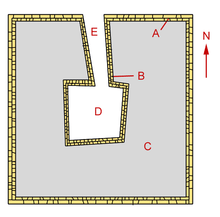

A: External wall

B: Internal wall

C: Stepping fill

D: Pit for the underground chambers

E: Pit for entry

The Pyramid of Raneferef was started with a base length of 65 metres (213 ft) and thus could have been the second-smallest king pyramid in the Old Kingdom of Egypt after the Pyramid of Unas. The planned height and side tilt are unknown, as the casing stones were never attached. The pyramid should have received a stepped core, covered by fine Tura limestones, but construction did not continue above the first step.[3]

Structure

The pyramid was not directly built on bedrock, but rather on a foundation made of large limestone blocks. These were cut from the local bedrock while excavating a pit at the pyramid's center. This pit was to receive the essential substructures (most notably the burial chamber), a construction technique common to all 5th dynasty pyramids.

The core layer of the pyramid comprises an exterior wall made of huge roughly-hewn limestone blocks, some up to 5 metres (16 ft) long, 1 metre (3.3 ft) wide and 1 metre (3.3 ft) deep, which formed the extent of the step in two rows. The pit for the burial chamber and the entrance were covered with a similar wall built from smaller blocks. This strategy allowed workers to work simultaneously on the foundation and on the first step of the pyramid. The height of the blocks, which were laid in horizontal layers, was about 1 metre (3.3 ft). Interspaces were filled with clay mortar. Apparently, the placement of the blocks was more careful in the corners than on the edges. The interior of the steps was filled with gravel, sand and mud. This offered a considerable saving of labor compared to the large and more accurately hewn limestone cores of 4th Dynasty pyramids, but also that the core is very sensitive to erosion. In fact, this construction technique is responsible for the ruinous state of all 5th and 6th Dynasty pyramids.[9]

The death of the pharaoh led to a stop in the construction works and design alterations were made to use the building for the funeral. The first step, about 7 metres (23 ft) high, received a cladding from rough limestones with a side slope of 78°, similar to a mastaba. This was covered with a layer of clay, in which flints were incised. The term "hill" (iat), found in the Abusir Papyri, might be connected with the primary hill myth.[3][8]

Substructure

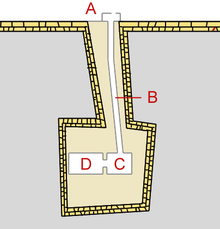

A: Entry with north chapel

B: Access passage

C: Antechamber

D: Burial chamber

The foundation of the pyramid was laid out in an open ditch. The ditch had an encircling wall, which extended to the first step of the pyramid and allowed simultaneous work on the foundation and the structure. The foundation was built in the same pattern as the Pyramid of Sahure. Access led from the north side of the pyramid downwards to the south direction and led to a slightly north-deviated horizontal passage. The lower area was faced with rose granite and had a portcullis slab barrier from the same material. Unusual and not verified in any other building was a further blocking device from jawlike, intertwined barriers in the centre of the horizontal passage. The burial chamber and the antechamber were as usual oriented east-to-west and faced with a pediment ceiling from fine limestone and a chamber cladding from the same material. Cladding as well as pediment ceiling were heavily damaged through stone robbery. Today, only single fragments of the foundation in the pit exist.[10]

Despite the devastation, the Czech group found the funerary goods and even the king's mummy, all in the substructure. In the burial chamber was a sarcophagus from rose granite, of which only a few fragments were preserved. Also found were fragments from the four canopic jars from alabaster and sacrifice jars from the same material.[11]

In all probability the mummified remains of the roughly 20 to 25 year old ruler belong – according to analysis of the archeological circumstances of finding and the anthropological study – to Pharaoh Raneferef.[11]

Pyramid complex

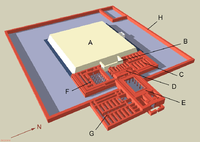

A: Pyramid stump B: Interior temple C: Stack-room

D: Funery temple E: Entry of the temple

F: Gallery G: Sanctuary of the Knife H: Stockade

Elements such as the causeway, the valley temple and the cult pyramid are missing due to discontinuation of the building work upon the king's premature death. Only buildings which were important for the burial and funerary cult were accomplished by his successor, then, unusually, expanded by the latter's successor.[12]

Mortuary temple

The small, possibly improvised temple on the eastside of the pyramid was constructed in the first building phase of the mortuary temple. The limestone temple has a north-south orientation. A step ramp enables entry from the southeast. This temple had a mandatory offering hall as well as a room for the ritual purgation on the entry. Imprints of an altar were at that time verifiable. A false door was located on the west wall, which contained gold-plated inscriptions.[9] Offerings such as a bull head and sacrificial vessels were found below the paving of the temple. There might have been two boat pits at the temple for worship boats. No evidence was found in the remains for the builder, thus the direct successor of Raneferef is unknown. It is believed that short-ruling Shepseskare was the successor, as seal impressions of him were found in the area of the mortuary temple.[12][13]

The temple complex was heavily extended in the second phase under Pharaoh Niuserre. Compared to the initial temple, the building material was, with a few exceptions, mud brick. This new temple area also had a north-southern direction, but extended over the whole length of the eastside of the truncated pyramid and encompassed the initial temple. The northern third of the new building contained two-storeyed storerooms. The middle part featured an entrance portico with two pillars and behind five oblong rooms, which are more reminiscent of storerooms than of the usual statue chapels. One chamber was later breached as an entry to the inner temple, while another chamber was sealed and incorporated the fire-damaged remniscents of the two worship boats. The storage area also housed the temple archive, as there was no valley temple in this complex.[9] The southern temple area is only found in this pyramid complex. It had a large hall, surrounded by twenty wooden lotus pillars. The roof was decorated with golden stars on a dark-blue heaven. This area included fragments of ruler statues, worship items and wooden statuettes of prisoners of war.[12]

A third construction period also under Niuserre extended the temple to an eastern entry area and gave it the period's typical T-shaped arrangement. Here, the building material was also mainly mud brick. This expansion included a monumental entry decorated with two papyrus columns from limestone, an entry hall and a subsequent open column court with 22 wooden round columns.[12]

During the rule of Djedkare, the priests of the mortuary cult built simple brick accommodations in the column court. The ruler cult of Raneferef was performed until the end of the 6th Dynasty, but went defunct in the following turmoils after the end of this dynasty. A short-lived revival of the cult took place in the 12th Dynasty.[12]

Sanctuary of the Knife

The so-called "Sanctuary of the Knife" was built outside the enclosure wall east of the southern temple section and south of the future entry leaves constructed in the second building phase. It was a ritual slaughterhouse for sacrificial animals for the ruler cult. The function and the description of the sanctuary is verified through papyri in the mortuary temple of Neferirkare. The building was constructed from mud brick and its external wall had round corners. The northern part of the sanctuary included an open slaughterhouse as well as in the north-east corner a realm for dissection of animals and conservation of meat. The middle and southern part of the building occupied the warehouse for the storage of meat. The meat was possibly dried in the roof terrace.[14] According to the Abusir papyri, 130 bulls were sacrificed in this sanctuary during a ten-day feast.[3]

The Sanctuary of the Knife lost its function in the third building period and was then used as a storage room, until it was destroyed in the first half of the 6th Dynasty.[3][14]

Circular wall

The circular wall of the complex was composed of a massive adobe wall, with corners consolidated with limestone blocks. A part of the court in the north-western corner was sectioned. The purpose of this separation is unknown.[14]

Sun sanctuary

In addition to the pyramid complex, Raneferef established a sun temple by the name of hetep re ("Re's offering table"), according to inscriptions and cylinder seals. It is assumed that it is located somewhere near Abusir, although no remnants of it have been found to date. After Raneferef's death, the sun temple of Niuserre may have been built over that of Raneferef.[15][16]

See also

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- List of megalithic sites

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (in German) T. Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag, 1996, pp. 261–262

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Verner 1999, pp. 336–345 Neferefre's (Unfinished) Pyramid

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Lehner 1997, pp. 146–148

- ↑ Verner 1999, p. 336

- ↑ Verner 1999, p. 338

- ↑ Verner 1999, p. 337

- ↑ Lehner 1997, pp. 106–107

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Verner 1999, p. 331

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 (in German) Rainer Stadelmann: Die ägyptischen Pyramiden. Vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder. pp. 174–175

- ↑ Verner 1999, pp. 339–340

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Verner 1999, pp. 340–341

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Verner 1999, pp. 341–345

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. In: Archiv Orientální. volume 69, Prag 2001, p. 396 (PDF)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Verner 1999, p. 344

- ↑ (in German) Susanne Voß: Untersuchungen zu den Sonnenheiligtümern der 5. Dynastie. Bedeutung und Funktion eines singulären Tempeltyps im Alten Reich. Hamburg 2004, pp. 153–155 (PDF)

- ↑ (in German) Miroslav Verner: Die Sonnenheiligtümer der 5. Dynastie. In: Sokar, 10th edition, 2005, p. 44

Further reading

General

- Hawass, Zahi (2003). The Treasures of the Pyramids. Amalgamated Book. pp. 249–251. ISBN 9788880952336.

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc. ISBN 9780500285473.

- Verner, Miroslav (1999). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 978-0802117038.

Specific

- Landgráfová, Renata : Abusir XIV. Faience Inlays from the Funerary Temple of King Raneferef. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule, Miroslav Verner, Hana Vymazalova: Abusir X. The Pyramid Complex of Raneferef. The Papyrus Archive. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006.

- Posener-Kriéger, Paule : Quelques pièces du matériel cultuel du temple funéraire de Rêneferef. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. (MDIAK) volume 47), von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 293–304

- Verner, Miroslav et al.: Abusir IX: The Pyramid Complex of Raneferef, I: The Archaeology. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006, ISBN 8020013571

- Verner, Miroslav : Les sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 16 planches] (= Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. volume 85). 1985, pp. 267–280 with XLIV-LIX suppl.

- Verner, Miroslav : Supplément aux sculptures de Rêneferef découvertes à Abousir [avec 4 planches] (=Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´archéologie orientale. volume 86). 1986, pp. 361-366 (PDF)

- Vlčková, Petra : Abusir XV. Stone Vessels from the Mortuary Complex of Raneferef at Abusir. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prag 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Neferefre. |

- Alan Winston: The Pyramid of Neferefre (Raneferer) at Abusir

- Pictures of the pyramid

- Layout of the pyramid

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||