Pyramid of Menkaure

| Menkaure's Pyramid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Menkaure | |

| Coordinates | 29°58′21″N 31°07′42″E / 29.97250°N 31.12833°ECoordinates: 29°58′21″N 31°07′42″E / 29.97250°N 31.12833°E |

| Type | True Pyramid |

| Height | 65.5 metres (215 ft) |

| Base | 103.4 metres (339 ft) |

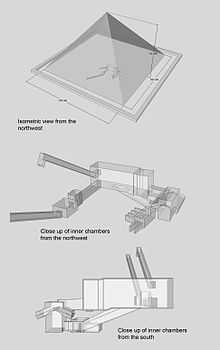

The Pyramid of Menkaure, located on the Giza Plateau in the southwestern outskirts of Cairo, Egypt, is the smallest of the three main Pyramids of Giza. It is thought to have been built to serve as the tomb of the fourth dynasty Egyptian Pharaoh Menkaure.

Size and construction

Menkaure's pyramid had an original height of 65.5 metres (215 feet) and was the smallest of the three major pyramids at the Giza Necropolis. It now stands at 61 m (204 ft) tall with a base of 108.5 m. Its angle of incline is approximately 51°20′25″. It was constructed of limestone and granite. The first sixteen courses of the exterior were made of granite. The upper portion was cased in the normal manner with Tura limestone. Part of the granite was left in the rough. Incomplete projects such as this pyramid help archaeologists understand the methods used to build pyramids and temples. South of the pyramid of Menkaure are 3 satellite pyramids, none of which appear to have been completed. The largest is made partly of granite, like the main pyramid. Neither of the other 2 progressed beyond the construction of the inner core.[1]

Herodotus's legend

Menkaure was allegedly a much more benevolent Pharaoh than his predecessors. According to legends related by Herodotus, he wrote the following:

"This Prince (Mycerinus) disapproved of the conduct of his father, reopened the temples and allowed the people, who were ground down to the lowest point of misery, to return to their occupations and to resume the practice of sacrifice. His justice in the decision of causes was beyond that of all the former kings. The Egyptians praise him in this respect more highly than any other monarchs, declaring that he not only gave his judgements with fairness, but also, when anyone was dissatisfied with his sentence, made compensation to him out of his own purse and thus pacified his anger."

The Gods, however, ordained that Egypt should suffer tyrannical rulers for a hundred and fifty years. According to this legend, Herodotus goes on:

"An oracle reached him from the town of Buto, stating that 'six years only shalt thou live upon this earth, and in the seventh thou shalt end thy days'. Mycerinus, indignant, sent an angry message to the oracle, reproaching the god with his injustice -'My father and uncle,' he said 'though they shut up the temples, took no thought of the gods and destroyed multitudes of men, nevertheless enjoyed a long life; I, who am pious, am to die soon!' There came in reply a second message from the oracle - 'for this very reason is thy life brought so quickly to a close - thou hast not done as it behoved thee. Egypt was fated to suffer affliction one hundred and fifty years - the two kings who preceded thee upon the throne understood this - thou hast not understood it.' Mycerinus, when this answer reached him, and perceiving that his doom was fixed, had lamps prepared, which he lighted every day at eventime, and feasted and enjoyed himself unceasingly both day and night, moving about in the marsh-country and the woods, and visiting all the places he heard were agreeable sojourns. His wish was to prove the oracle false, by turning night into days and so living twelve years in the space of six."[1][2] It should be noted that Herodotus visited Egypt over 2,000 years after the Giza pyramids were built and much of his 'histories' have been dismissed as apocryphal.

Temple complex

In the mortuary temple the foundations and the inner core were made of limestone. The floors were begun with granite and granite facings were added to some of the walls. The foundations of the valley temple were made of stone. However they were both finished with crude bricks. Reisner estimated that some of the blocks of local stone in the walls of the mortuary temple weighed as much as 220 tons, while the heaviest granite ashlars imported from Aswan weighed more than 30 tons. It was not unusual for a son or successor to complete a temple when a Pharaoh died, so it is not unreasonable to assume that Shepseskaf finished the temples with crude brick. There was an inscription in the mortuary temple that said he "made it (the temple) as his monument for his father, the king of upper and lower Egypt." During excavations of the temples Reisner found a large number of statues mostly of Menkaure alone and as a member of a group. These were all carved in the naturalistic style of the old kingdom with a high degree of detail evident.[1]

Age and location

The pyramid's date of construction is unknown, because Menkaure's reign has not been accurately defined, but it was probably completed in the 26th century BC. It lies a few hundred meters southwest of its larger neighbors, the Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Pyramid of Khufu in the Giza necropolis.

Coffin and sarcophagus

Richard William Howard Vyse, who first visited Egypt in 1835, discovered in the upper antechamber the remains of a wooden anthropoid coffin inscribed with Menkaure's name and containing human bones. This is now considered to be a substitute coffin from the Saite period, and radiocarbon dating on the bones determined them to be less than 2,000 years old, suggesting either an all-too-common bungled handling of remains from another site, or access to the pyramid during Roman times. Deeper into the pyramid, Vyse came upon a beautiful basalt sarcophagus, rich in detail with a bold projecting cornice. Unfortunately, this sarcophagus now lies at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, having sunk on October 13, 1838, with the ship Beatrice, as she made her way between Malta and Cartagena, on the way to Great Britain.[4] It was one of only a handful of Old Kingdom sarcophagi to survive into the modern period. The anthropoid coffin, however, was successfully transported on a separate ship and may be seen today at the British Museum.[4]

Attempted demolition

At the end of the twelfth century al-Malek al-Aziz Othman ben Yusuf, Saladin's son and heir, attempted to demolish the pyramids, starting with Menkaure's. The workmen whom Al-Aziz had recruited to demolish the pyramid found it almost as expensive to destroy as to build. They stayed at their job for eight months. They were not able to remove more than one or two stones each day at a cost of tiring themselves out utterly. Some used wedges and levers to move the stones, while others used ropes to pull them down. When a stone fell, it would bury itself in the sand, requiring extraordinary efforts to free it. Wedges were used to split the stones into several pieces, and a cart was used to carry it to the foot of the escarpment, where it was left. Far from accomplishing what they intended to do, they merely spoiled the pyramid by leaving a large vertical gash in its north face.[5][6]

See also

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- List of megalithic sites

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Edwards, Dr. I.E.S.: The Pyramids of Egypt 1986/1947 p. 147-163

- ↑ p. 129-133 Herodotus Book II (Rawlinson's translation)

- ↑ Lehner, Mark (2001). The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 221. ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dr. Zahi Hawass. "The Pyramids at Giza: Khafre and Menkaure". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ↑ Stewert, Desmond and editors of the Newsweek Book Division "The Pyramids and Sphinx" 1971 p. 101

- ↑ Lehner, Mark The Complete Pyramids, London: Thames and Hudson (1997)p.41 ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

Further reading

- Verner, Miroslav, The Pyramids – Their Archaeology and History, Atlantic Books, 2001, ISBN 1-84354-171-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Menkaure. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||