Pushdown automaton

In computer science, a pushdown automaton (PDA) is a type of automaton that employs a stack.

Pushdown automata are used in theories about what can be computed by machines. They are more capable than finite-state machines but less capable than Turing machines. Deterministic pushdown automata can recognize all deterministic context-free languages while nondeterministic ones can recognize all context-free languages. Mainly the former are used in parser design.

The term "pushdown" refers to the fact that the stack can be regarded as being "pushed down" like a tray dispenser at a cafeteria, since the operations never work on elements other than the top element. A stack automaton, by contrast, does allow access to and operations on deeper elements. Stack automata can recognize a strictly larger set of languages than pushdown automata.[1] A nested stack automaton allows full access, and also allows stacked values to be entire sub-stacks rather than just single finite symbols.

The remainder of this article describes the nondeterministic pushdown automaton.

Operation

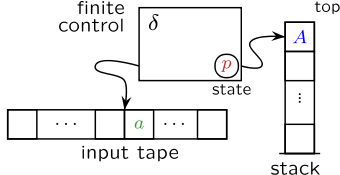

Pushdown automata differ from finite state machines in two ways:

- They can use the top of the stack to decide which transition to take.

- They can manipulate the stack as part of performing a transition.

Pushdown automata choose a transition by indexing a table by input signal, current state, and the symbol at the top of the stack. This means that those three parameters completely determine the transition path that is chosen. Finite state machines just look at the input signal and the current state: they have no stack to work with. Pushdown automata add the stack as a parameter for choice.

Pushdown automata can also manipulate the stack, as part of performing a transition. Finite state machines choose a new state, the result of following the transition. The manipulation can be to push a particular symbol to the top of the stack, or to pop off the top of the stack. The automaton can alternatively ignore the stack, and leave it as it is. The choice of manipulation (or no manipulation) is determined by the transition table.

Put together: Given an input signal, current state, and stack symbol, the automaton can follow a transition to another state, and optionally manipulate (push or pop) the stack.

In general, pushdown automata may have several computations on a given input string, some of which may be halting in accepting configurations. If only one computation exists for all accepted strings, the result is a deterministic pushdown automaton (DPDA) and the language of these strings is a deterministic context-free language. Not all context-free languages are deterministic.[2] As a consequence of the above the DPDA is a strictly weaker variant of the PDA and there exists no algorithm for converting a PDA to an equivalent DPDA, if such a DPDA exists.

If we allow a finite automaton access to two stacks instead of just one, we obtain a more powerful device, equivalent in power to a Turing machine. A linear bounded automaton is a device which is more powerful than a pushdown automaton but less so than a Turing machine.

Relation to backtracking

Nondeterministic PDAs are able to handle situations where more than one choice of action is available. In principle it is enough to create in every such case new automaton instances that will handle the extra choices. The problem with this approach is that in practice most of these instances fail. This can severely affect the automaton's performance as the execution of multiple instances is a costly operation. Situations such as these can be identified in the design phase of the automaton by examining the grammar the automaton uses. This makes possible the use of backtracking in every such case in order to improve the performance of pushdown automaton.

Formal definition

We use standard formal language notation:  denotes the set of strings over alphabet

denotes the set of strings over alphabet  and

and  denotes the empty string.

denotes the empty string.

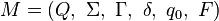

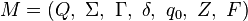

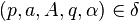

A PDA is formally defined as a 7-tuple:

where

where

is a finite set of states

is a finite set of states is a finite set which is called the input alphabet

is a finite set which is called the input alphabet is a finite set which is called the stack alphabet

is a finite set which is called the stack alphabet is a finite subset of

is a finite subset of  , the transition relation.

, the transition relation. is the start state

is the start state is the initial stack symbol

is the initial stack symbol is the set of accepting states

is the set of accepting states

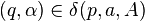

An element  is a transition of

is a transition of  . It has the intended meaning that

. It has the intended meaning that  , in state

, in state  , with

, with  on the input and with

on the input and with  as topmost stack symbol, may read

as topmost stack symbol, may read  , change the state to

, change the state to  , pop

, pop  , replacing it by pushing

, replacing it by pushing  . The

. The  component of the transition relation is used to formalize that the PDA can either read a letter from the input, or proceed leaving the input untouched.

component of the transition relation is used to formalize that the PDA can either read a letter from the input, or proceed leaving the input untouched.

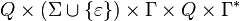

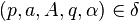

In many texts the transition relation is replaced by an (equivalent) formalization, where

-

is the transition function, mapping

is the transition function, mapping  into finite subsets of

into finite subsets of  .

.

Here  contains all possible actions in state

contains all possible actions in state  with

with  on the stack, while reading

on the stack, while reading  on the input. One writes

on the input. One writes  for the function precisely when

for the function precisely when  for the relation. Note that finite in this definition is essential.

for the relation. Note that finite in this definition is essential.

Computations

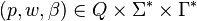

In order to formalize the semantics of the pushdown automaton a description of the current situation is introduced. Any 3-tuple  is called an instantaneous description (ID) of

is called an instantaneous description (ID) of  , which includes the current state, the part of the input tape that has not been read, and the contents of the stack (topmost symbol written first). The transition relation

, which includes the current state, the part of the input tape that has not been read, and the contents of the stack (topmost symbol written first). The transition relation  defines the step-relation

defines the step-relation  of

of  on instantaneous descriptions. For instruction

on instantaneous descriptions. For instruction  there exists a step

there exists a step  , for every

, for every  and every

and every  .

.

In general pushdown automata are nondeterministic meaning that in a given instantaneous description  there may be several possible steps. Any of these steps can be chosen in a computation.

With the above definition in each step always a single symbol (top of the stack) is popped, replacing it with as many symbols as necessary. As a consequence no step is defined when the stack is empty.

there may be several possible steps. Any of these steps can be chosen in a computation.

With the above definition in each step always a single symbol (top of the stack) is popped, replacing it with as many symbols as necessary. As a consequence no step is defined when the stack is empty.

Computations of the pushdown automaton are sequences of steps. The computation starts in the initial state  with the initial stack symbol

with the initial stack symbol  on the stack, and a string

on the stack, and a string  on the input tape, thus with initial description

on the input tape, thus with initial description  .

There are two modes of accepting. The pushdown automaton either accepts by final state, which means after reading its input the automaton reaches an accepting state (in

.

There are two modes of accepting. The pushdown automaton either accepts by final state, which means after reading its input the automaton reaches an accepting state (in  ), or it accepts by empty stack (

), or it accepts by empty stack ( ), which means after reading its input the automaton empties its stack. The first acceptance mode uses the internal memory (state), the second the external memory (stack).

), which means after reading its input the automaton empties its stack. The first acceptance mode uses the internal memory (state), the second the external memory (stack).

Formally one defines

-

with

with  and

and  (final state)

(final state) -

with

with  (empty stack)

(empty stack)

Here  represents the reflexive and transitive closure of the step relation

represents the reflexive and transitive closure of the step relation  meaning any number of consecutive steps (zero, one or more).

meaning any number of consecutive steps (zero, one or more).

For each single pushdown automaton these two languages need to have no relation: they may be equal but usually this is not the case. A specification of the automaton should also include the intended mode of acceptance. Taken over all pushdown automata both acceptance conditions define the same family of languages.

Theorem. For each pushdown automaton  one may construct a pushdown automaton

one may construct a pushdown automaton  such that

such that  , and vice versa, for each pushdown automaton

, and vice versa, for each pushdown automaton  one may construct a pushdown automaton

one may construct a pushdown automaton  such that

such that

Example

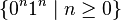

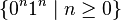

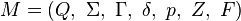

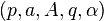

The following is the formal description of the PDA which recognizes the language  by final state:

by final state:

(by final state)

(by final state) , where

, where

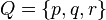

states:

input alphabet:

stack alphabet:

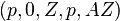

start state:

start stack symbol:

accepting states:

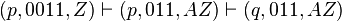

The transition relation  consists of the following six instructions:

consists of the following six instructions:

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

.

.

In words, the first two instructions say that in state  any time the symbol

any time the symbol  is read, one

is read, one  is pushed onto the stack. Pushing symbol

is pushed onto the stack. Pushing symbol  on top of another

on top of another  is formalized as replacing top

is formalized as replacing top  by

by  (and similarly for pushing symbol

(and similarly for pushing symbol  on top of a

on top of a  ).

).

The third and fourth instructions say that, at any moment the automaton may move from state  to state

to state  .

.

The fifth instruction says that in state  , for each symbol

, for each symbol  read, one

read, one  is popped.

is popped.

Finally, the sixth instruction says that the machine may move from state  to accepting state

to accepting state  only when the stack consists of a single

only when the stack consists of a single  .

.

There seems to be no generally used representation for PDA. Here we have depicted the instruction  by an edge from state

by an edge from state  to state

to state  labelled by

labelled by  (read

(read  ; replace

; replace  by

by  ).

).

Understanding the computation process

The following illustrates how the above PDA computes on different input strings. The subscript  from the step symbol

from the step symbol  is here omitted.

is here omitted.

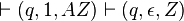

(a) Input string = 0011. There are various computations, depending on the moment the move from state  to state

to state  is made. Only one of these is accepting.

is made. Only one of these is accepting.

- (i)

. The final state is accepting, but the input is not accepted this way as it has not been read.

. The final state is accepting, but the input is not accepted this way as it has not been read.

- (ii)

. No further steps possible.

. No further steps possible.

- (iii)

. Accepting computation: ends in accepting state, while complete input has been read.

. Accepting computation: ends in accepting state, while complete input has been read.

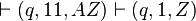

(b) Input string = 00111. Again there are various computations. None of these is accepting.

- (i)

. The final state is accepting, but the input is not accepted this way as it has not been read.

. The final state is accepting, but the input is not accepted this way as it has not been read.

- (ii)

. No further steps possible.

. No further steps possible.

- (iii)

. The final state is accepting, but the input is not accepted this way as it has not been (completely) read.

. The final state is accepting, but the input is not accepted this way as it has not been (completely) read.

PDA and context-free languages

Every context-free grammar can be transformed into an equivalent nondeterministic pushdown automaton. The derivation process of the grammar is simulated in a leftmost way. Where the grammar rewrites a nonterminal, the PDA takes the topmost nonterminal from its stack and replaces it by the right-hand part of a grammatical rule (expand). Where the grammar generates a terminal symbol, the PDA reads a symbol from input when it is the topmost symbol on the stack (match). In a sense the stack of the PDA contains the unprocessed data of the grammar, corresponding to a pre-order traversal of a derivation tree.

Technically, given a context-free grammar, the PDA is constructed as follows.

-

for each rule

for each rule  (expand)

(expand) -

for each terminal symbol

for each terminal symbol  (match)

(match)

As a result we obtain a single state pushdown automata, the state here is  , accepting the context-free language by empty stack. Its initial stack symbol equals the axiom of the context-free grammar.

, accepting the context-free language by empty stack. Its initial stack symbol equals the axiom of the context-free grammar.

The converse, finding a grammar for a given PDA, is not that easy. The trick is to code two states of the PDA into the nonterminals of the grammar.

Theorem. For each pushdown automaton  one may construct a context-free grammar

one may construct a context-free grammar  such that

such that  .

.

Generalized pushdown automaton (GPDA)

A GPDA is a PDA which writes an entire string of some known length to the stack or removes an entire string from the stack in one step.

A GPDA is formally defined as a 6-tuple:

where Q,  ,

,  , q0 and F are defined the same way as a PDA.

, q0 and F are defined the same way as a PDA.

:

:

is the transition function.

Computation rules for a GPDA are the same as a PDA except that the ai+1's and bi+1's are now strings instead of symbols.

GPDA's and PDA's are equivalent in that if a language is recognized by a PDA, it is also recognized by a GPDA and vice versa.

One can formulate an analytic proof for the equivalence of GPDA's and PDA's using the following simulation:

Let  (q1, w, x1x2...xm)

(q1, w, x1x2...xm)  (q2, y1y2...yn) be a transition of the GPDA

(q2, y1y2...yn) be a transition of the GPDA

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

Construct the following transitions for the PDA:

(q1, w, x1)

(q1, w, x1)  (p1,

(p1,  )

)

(p1,

(p1,  , x2)

, x2)  (p2,

(p2,  )

)

(pm-1,

(pm-1,  , xm)

, xm)  (pm,

(pm,  )

)

(pm,

(pm,  ,

,  )

)  (pm+1, yn)

(pm+1, yn)

(pm+1,

(pm+1,  ,

,  )

)  (pm+2, yn-1)

(pm+2, yn-1)

(pm+n-1,

(pm+n-1,  ,

,  )

)  (q2, y1)

(q2, y1)

Stack automaton

As a generalization of pushdown automata, Ginsburg, Greibach, and Harrison (1967) investigated stack automata, which may additionally step left or right in the input string (surrounded by special endmarker symbols to prevent slipping out), and step up or down in the stack in read-only mode.[3][4] A stack automaton is called nonerasing if it never pops from the stack. The class of languages accepted by nondeterministic, nonerasing stack automata is NSPACE(n2), which is a superset of the context-sensitive languages.[1] The class of languages accepted by deterministic, nonerasing stack automata is DSPACE(n⋅log(n)).[1]

See also

- Stack machine

- Context-free grammar

- Finite automaton

- Counter automaton

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 John E. Hopcroft, Jeffrey D. Ullman (1967). "Nonerasing Stack Automata" (PDF). J. Computer and System Sciences 1 (2): 166–186. doi:10.1016/s0022-0000(67)80013-8.

- ↑ John E. Hopcroft, Rajeev Motwani, Jeffrey D. Ullman (2003). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation. Addison Wesley. Here: Sect.6.4.3, p.249: The set of even-length palindromes of bits can't be recognized by a deterministic PDA, but is a context-free language, with the grammar S → ε | 0S0 | 1S1.

- ↑ Seymour Ginsburg, Sheila A. Greibach and Michael A. Harrison (1967). "Stack Automata and Compiling". J. ACM 14 (1): 172–201. doi:10.1145/321371.321385.

- ↑ Seymour Ginsburg, Sheila A. Greibach and Michael A. Harrison (1967). "One-Way Stack Automata". J. ACM 14 (2): 389–418. doi:10.1145/321386.321403.

- Michael Sipser (1997). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 0-534-94728-X. Section 2.2: Pushdown Automata, pp. 101–114.

- Jean-Michel Autebert, Jean Berstel, Luc Boasson, Context-Free Languages and Push-Down Automata, in: G. Rozenberg, A. Salomaa (eds.), Handbook of Formal Languages, Vol. 1, Springer-Verlag, 1997, 111-174.

External links

- JFLAP, simulator for several types of automata including nondeterministic pushdown automata

| |||||||||||||||||||