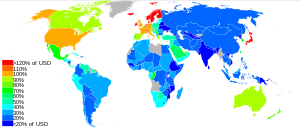

Purchasing power parity

_per_capita_by_countries.png)

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a component of some economic theories and is a technique used to determine the relative value of different currencies.

Theories that invoke purchasing power parity assume that in some circumstances (for example, as a long-run tendency) it would cost exactly the same number of, say, US dollars to buy euros and then to use the proceeds to buy a market basket of goods as it would cost to use those dollars directly in purchasing the market basket of goods.

The concept of purchasing power parity allows one to estimate what the exchange rate between two currencies would have to be in order for the exchange to be at par with the purchasing power of the two countries' currencies. Using that PPP rate for hypothetical currency conversions, a given amount of one currency thus has the same purchasing power whether used directly to purchase a market basket of goods or used to convert at the PPP rate to the other currency and then purchase the market basket using that currency. Observed deviations of the exchange rate from purchasing power parity are measured by deviations of the real exchange rate from its PPP value of 1.

PPP exchange rates help to minimize misleading international comparisons that can arise with the use of market exchange rates. For example, suppose that two countries produce the same physical amounts of goods as each other in each of two different years. Since market exchange rates fluctuate substantially, when the GDP of one country measured in its own currency is converted to the other country's currency using market exchange rates, one country might be inferred to have higher real GDP than the other country in one year but lower in the other; both of these inferences would fail to reflect the reality of their relative levels of production. But if one country's GDP is converted into the other country's currency using PPP exchange rates instead of observed market exchange rates, the false inference will not occur.

Concept

The idea originated with the School of Salamanca in the 16th century and was developed in its modern form by Gustav Cassel in 1918.[2][3] The concept is based on the law of one price, where in the absence of transaction costs and official trade barriers, identical goods will have the same price in different markets when the prices are expressed in the same currency.[4]

Another interpretation is that the difference in the rate of change in prices at home and abroad—the difference in the inflation rates—is equal to the percentage depreciation or appreciation of the exchange rate.

Deviations from parity imply differences in purchasing power of a "basket of goods" across countries, which means that for the purposes of many international comparisons, countries' GDPs or other national income statistics need to be "PPP-adjusted" and converted into common units. The best-known purchasing power adjustment is the Geary–Khamis dollar (the "international dollar"). The real exchange rate is then equal to the nominal exchange rate, adjusted for differences in price levels. If purchasing power parity held exactly, then the real exchange rate would always equal one. However, in practice the real exchange rates exhibit both short run and long run deviations from this value, for example due to reasons illuminated in the Balassa–Samuelson theorem.

There can be marked differences between purchasing power adjusted incomes and those converted via market exchange rates.[5] For example, the World Bank's World Development Indicators 2005 estimated that in 2003, one Geary-Khamis dollar was equivalent to about 1.8 Chinese yuan by purchasing power parity[6]—considerably different from the nominal exchange rate. This discrepancy has large implications; for instance, when converted via the nominal exchange rates GDP per capita in India is about US$1,704[7] while on a PPP basis it is about US$3,608.[8] At the other extreme, Denmark's nominal GDP per capita is around US$62,100, but its PPP figure is US$37,304.

Functions

The purchasing power parity exchange rate serves two main functions. PPP exchange rates can be useful for making comparisons between countries because they stay fairly constant from day to day or week to week and only change modestly, if at all, from year to year. Second, over a period of years, exchange rates do tend to move in the general direction of the PPP exchange rate and there is some value to knowing in which direction the exchange rate is more likely to shift over the long run.

Measurement

The PPP exchange-rate calculation is controversial because of the difficulties of finding comparable baskets of goods to compare purchasing power across countries.

Estimation of purchasing power parity is complicated by the fact that countries do not simply differ in a uniform price level; rather, the difference in food prices may be greater than the difference in housing prices, while also less than the difference in entertainment prices. People in different countries typically consume different baskets of goods. It is necessary to compare the cost of baskets of goods and services using a price index. This is a difficult task because purchasing patterns and even the goods available to purchase differ across countries.

Thus, it is necessary to make adjustments for differences in the quality of goods and services. Furthermore, the basket of goods representative of one economy will vary from that of another: Americans eat more bread; Chinese more rice. Hence a PPP calculated using the US consumption as a base will differ from that calculated using China as a base. Additional statistical difficulties arise with multilateral comparisons when (as is usually the case) more than two countries are to be compared.

Various ways of averaging bilateral PPPs can provide a more stable multilateral comparison, but at the cost of distorting bilateral ones. These are all general issues of indexing; as with other price indices there is no way to reduce complexity to a single number that is equally satisfying for all purposes. Nevertheless, PPPs are typically robust in the face of the many problems that arise in using market exchange rates to make comparisons.

For example, in 2005 the price of a gallon of gasoline in Saudi Arabia was USD 0.91, and in Norway the price was USD 6.27.[9] The significant differences in price wouldn't contribute to accuracy in a PPP analysis, despite all of the variables that contribute to the significant differences in price. More comparisons have to be made and used as variables in the overall formulation of the PPP.

When PPP comparisons are to be made over some interval of time, proper account needs to be made of inflationary effects.

Law of one price

Although it may seem as if PPPs and the law of one price are the same, there is a difference: the law of one price applies to individual commodities whereas PPP applies to the general price level. If the law of one price is true for all commodities then PPP is also therefore true; however, when discussing the validity of PPP, some argue that the law of one price does not need to be true exactly for PPP to be valid. If the law of one price is not true for a certain commodity, the price levels will not differ enough from the level predicted by PPP.[4]

The purchasing power parity theory states that the exchange rate between one currency and another currency is in equlibirium when their domestic purchasing powers at that rate of exchange are equivalent.

Big Mac Index

Another example of one measure of the law of one price, which underlies purchasing power parity, is the Big Mac Index, popularized by The Economist, which compares the prices of a Big Mac burger in McDonald's restaurants in different countries. The Big Mac Index is presumably useful because although it is based on a single consumer product that may not be typical, it is a relatively standardized product that includes input costs from a wide range of sectors in the local economy, such as agricultural commodities (beef, bread, lettuce, cheese), labor (blue and white collar), advertising, rent and real estate costs, transportation, etc.

In theory, the law of one price would hold that if, to take an example, the Canadian dollar were to be significantly overvalued relative to the U.S. dollar according to the Big Mac Index, that gap should be unsustainable because Canadians would import their Big Macs from or travel to the U.S. to consume them, thus putting upward demand pressure on the U.S. dollar by virtue of Canadians buying the U.S. dollars needed to purchase the U.S.-made Big Macs and simultaneously placing downward supply pressure on the Canadian dollar by virtue of Canadians selling their currency in order to buy those same U.S. dollars.

The alternative to this exchange rate adjustment would be an adjustment in prices, with Canadian McDonald's stores compelled to lower prices to remain competitive. Either way, the valuation difference should be reduced assuming perfect competition and a perfectly tradable good. In practice, of course, the Big Mac is not a perfectly tradable good and there may also be capital flows that sustain relative demand for the Canadian dollar. The difference in price may have its origins in a variety of factors besides direct input costs such as government regulations and product differentiation.[4]

However, in some emerging economies, Western fast food represents an expensive niche product priced well above the price of traditional staples—i.e. the Big Mac is not a mainstream 'cheap' meal as it is in the West, but a luxury import. This relates back to the idea of product differentiation: the fact that few substitutes for the Big Mac are available confers market power on McDonald's. For example, in India, the costs of local fast food like vada pav are comparative to what the Big Mac signifies in the U.S.A. [10] Additionally, with countries like Argentina that have abundant beef resources, consumer prices in general may not be as cheap as implied by the price of a Big Mac.

The following table, based on data from The Economist's January 2013 calculations, shows the under (−) and over (+) valuation of the local currency against the U.S. dollar in %, according to the Big Mac index. To take an example calculation, the local price of a Big Mac in Hong Kong when converted to U.S. dollars at the market exchange rate was $2.19, or 50% of the local price for a Big Mac in the U.S. of $4.37. Hence the Hong Kong dollar was deemed to be 50% undervalued relative to the U.S. dollar on a PPP basis.

| Country | Price level (% relative to the US)[11] |

|---|---|

| India | -59 |

| South Africa | -54 |

| Hong Kong | -50 |

| Ukraine | -47 |

| Egypt | -45 |

| Russia | -45 |

| Taiwan | -42 |

| China | -41 |

| Malaysia | -41 |

| Sri Lanka | -37 |

| Indonesia | -35 |

| Mexico | -34 |

| Philippines | -33 |

| Poland | -33 |

| Bangladesh | -32 |

| Saudi Arabia | -33 |

| Thailand | -33 |

| Pakistan | -32 |

| Lithuania | -30 |

| Latvia | -25 |

| UAE | -25 |

| South Korea | -22 |

| Japan | -20 |

| Singapore | -17 |

| Estonia | -16 |

| Czech Republic | -15 |

| Argentina | -13 |

| Hungary | -13 |

| Peru | -11 |

| Israel | -8 |

| Portugal | -8 |

| United Kingdom | -3 |

| New Zealand | -1 |

| Chile | 0 |

| United States | 0 |

| Costa Rica | 1 |

| Greece | 3 |

| Austria | 5 |

| Netherlands | 7 |

| Ireland | 8 |

| Spain | 9 |

| Turkey | 10 |

| Colombia | 11 |

| Australia | 12 |

| Euro area | 12 |

| France | 12 |

| Germany | 13 |

| Finland | 17 |

| Belgium | 18 |

| Denmark | 19 |

| Italy | 20 |

| Canada | 24 |

| Uruguay | 25 |

| Brazil | 29 |

| Switzerland | 63 |

| Sweden | 75 |

| Norway | 80 |

| Venezuela | 108 |

iPad Index

Like the Big Mac Index, the iPad index (elaborated by ComSec) compares an item's price in various locations. Unlike the Big Mac, however, each iPad is produced in the same place (except for the model sold in Brazil) and all iPads (within the same model) have identical performance characteristics. Price differences are therefore a function of transportation costs, taxes, and to a lesser extent, the prices that may be realized in individual markets. It is worth noting that an iPad will cost about twice as much in Argentina as in the United States.

| Country | Price (US Dollars)[12][13][14][15] |

|---|---|

| Argentina | $1,094.11 |

| Australia | $506.66 |

| Austria | $674.96 |

| Belgium | $618.34 |

| Brazil | $791.40 |

| Brunei | $525.52 |

| Canada (Montréal) | $557.18 |

| Canada (no tax) | $467.36 |

| Chile | $602.13 |

| China | $602.52 |

| Czech Republic | $676.69 |

| Denmark | $725.32 |

| Finland | $695.25 |

| France | $688.49 |

| Germany | $618.34 |

| Greece | $715.54 |

| Hong Kong | $501.52 |

| Hungary | $679.64 |

| India | $512.61 |

| Ireland | $630.73 |

| Italy | $674.96 |

| Japan | $501.56 |

| Luxembourg | $641.50 |

| Malaysia | $473.77 |

| Mexico | $591.62 |

| Netherlands | $683.08 |

| New Zealand | $610.45 |

| Norway | $655.92 |

| Philippines | $556.42 |

| Poland | $704.51 |

| Portugal | $688.49 |

| Russia | $596.08 |

| Singapore | $525.98 |

| Slovakia | $674.96 |

| Slovenia | $674.96 |

| South Africa | $559.38 |

| South Korea | $576.20 |

| Spain | $674.96 |

| Sweden | $706.87 |

| Switzerland | $617.58 |

| Taiwan | $538.34 |

| Thailand | $530.72 |

| Turkey | $656.96 |

| UAE | $544.32 |

| United Kingdom | $638.81 |

| US (California) | $546.91 |

| US (no tax) | $499.00 |

| Vietnam | $554.08 |

OECD comparative price levels

Each month, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development measures the difference in price levels between its member countries by calculating the ratios of PPPs for private final consumption expenditure to exchange rates. The OECD table below indicates the number of US dollars needed in each of the countries listed to buy the same representative basket of consumer goods and services that would cost 100 USD in the United States

According to the table, an American living or travelling in Switzerland on an income denominated in US dollars would find that country to be the most expensive of the group, having to spend 62% more US dollars to maintain a standard of living comparable to the USA in terms of consumption.

| Country | Price level (USA = 100) [16] |

|---|---|

| Australia | 123 |

| Austria | 99 |

| Belgium | 101 |

| Canada | 105 |

| Chile | 67 |

| Czech Republic | 59 |

| Denmark | 128 |

| Estonia | 71 |

| Finland | 113 |

| France | 100 |

| Germany | 94 |

| Greece | 78 |

| Hungary | 52 |

| Iceland | 111 |

| Ireland | 109 |

| Israel | 109 |

| Italy | 94 |

| Japan | 96 |

| Korea | 84 |

| Luxembourg | 112 |

| Mexico | 66 |

| Netherlands | 102 |

| New Zealand | 118 |

| Norway | 134 |

| Poland | 51 |

| Portugal | 73 |

| Slovak Republic | 63 |

| Slovenia | 75 |

| Spain | 84 |

| Sweden | 109 |

| Switzerland | 162 |

| Turkey | 61 |

| United Kingdom | 121 |

| United States | 100 |

Measurement issues

In addition to methodological issues presented by the selection of a basket of goods, PPP estimates can also vary based on the statistical capacity of participating countries. The International Comparison Program, which PPP estimates are based on, require the disaggregation of national accounts into production, expenditure or (in some cases) income, and not all participating countries routinely disaggregate their data into such categories.

Some aspects of PPP comparison are theoretically impossible or unclear. For example, there is no basis for comparison between the Ethiopian laborer who lives on teff with the Thai laborer who lives on rice, because teff is not commercially available in Thailand and rice is not in Ethiopia, so the price of rice in Ethiopia or teff in Thailand cannot be determined. As a general rule, the more similar the price structure between countries, the more valid the PPP comparison.

PPP levels will also vary based on the formula used to calculate price matrices. Different possible formulas include GEKS-Fisher, Geary-Khamis, IDB, and the superlative method. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

Linking regions presents another methodological difficulty. In the 2005 ICP round, regions were compared by using a list of some 1,000 identical items for which a price could be found for 18 countries, selected so that at least two countries would be in each region. While this was superior to earlier "bridging" methods, which do not fully take into account differing quality between goods, it may serve to overstate the PPP basis of poorer countries, because the price indexing on which PPP is based will assign to poorer countries the greater weight of goods consumed in greater shares in richer countries.

Need for adjustments to GDP

The exchange rate reflects transaction values for traded goods between countries in contrast to non-traded goods, that is, goods produced for home-country use. Also, currencies are traded for purposes other than trade in goods and services, e.g., to buy capital assets whose prices vary more than those of physical goods. Also, different interest rates, speculation, hedging or interventions by central banks can influence the foreign-exchange market.

The PPP method is used as an alternative to correct for possible statistical bias. The Penn World Table is a widely cited source of PPP adjustments, and the so-called Penn effect reflects such a systematic bias in using exchange rates to outputs among countries.

For example, if the value of the Mexican peso falls by half compared to the US dollar, the Mexican Gross Domestic Product measured in dollars will also halve. However, this exchange rate results from international trade and financial markets. It does not necessarily mean that Mexicans are poorer by a half; if incomes and prices measured in pesos stay the same, they will be no worse off assuming that imported goods are not essential to the quality of life of individuals. Measuring income in different countries using PPP exchange rates helps to avoid this problem.

PPP exchange rates are especially useful when official exchange rates are artificially manipulated by governments. Countries with strong government control of the economy sometimes enforce official exchange rates that make their own currency artificially strong. By contrast, the currency's black market exchange rate is artificially weak. In such cases, a PPP exchange rate is likely the most realistic basis for economic comparison.

Extrapolating PPP rates

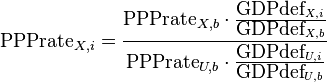

Since global PPP estimates —such as those provided by the ICP— are not calculated annually, but for a single year, PPP exchange rates for years other than the benchmark year need to be extrapolated.[17] One way of doing this is by using the country's GDP deflator. To calculate a country's PPP exchange rate in Geary–Khamis dollars for a particular year, the calculation proceeds in the following manner:

Where PPPrateX,i is the PPP exchange rate of country X for year i, PPPrateX,b is the PPP exchange rate of country X for the benchmark year, PPPrateU,b is the PPP exchange rate of the United States (US) for the benchmark year (equal to 1), GDPdefX,i is the GDP deflator of country X for year i, GDPdefX,b is the GDP deflator of country X for the benchmark year, GDPdefU,i is the GDP deflator of the US for year i, and GDPdefU,b is the GDP deflator of the US for the benchmark year.

Difficulties

There are a number of reasons that different measures do not perfectly reflect standards of living.

Range and quality of goods

The goods that the currency has the "power" to purchase are a basket of goods of different types:

- Local, non-tradable goods and services (like electric power) that are produced and sold domestically.

- Tradable goods such as non-perishable commodities that can be sold on the international market (like diamonds).

The more that a product falls into category 1, the further its price will be from the currency exchange rate, moving towards the PPP exchange rate. Conversely, category 2 products tend to trade close to the currency exchange rate. (See also Penn effect).

More processed and expensive products are likely to be tradable, falling into the second category, and drifting from the PPP exchange rate to the currency exchange rate. Even if the PPP "value" of the Ethiopian currency is three times stronger than the currency exchange rate, it won't buy three times as much of internationally traded goods like steel, cars and microchips, but non-traded goods like housing, services ("haircuts"), and domestically produced crops. The relative price differential between tradables and non-tradables from high-income to low-income countries is a consequence of the Balassa–Samuelson effect and gives a big cost advantage to labour-intensive production of tradable goods in low income countries (like Ethiopia), as against high income countries (like Switzerland).

The corporate cost advantage is nothing more sophisticated than access to cheaper workers, but because the pay of those workers goes farther in low-income countries than high, the relative pay differentials (inter-country) can be sustained for longer than would be the case otherwise. (This is another way of saying that the wage rate is based on average local productivity and that this is below the per capita productivity that factories selling tradable goods to international markets can achieve.) An equivalent cost benefit comes from non-traded goods that can be sourced locally (nearer the PPP-exchange rate than the nominal exchange rate in which receipts are paid). These act as a cheaper factor of production than is available to factories in richer countries.

The Bhagwati–Kravis–Lipsey view provides a somewhat different explanation from the Balassa–Samuelson theory. This view states that price levels for nontradables are lower in poorer countries because of differences in endowment of labor and capital, not because of lower levels of productivity. Poor countries have more labor relative to capital, so marginal productivity of labor is greater in rich countries than in poor countries. Nontradables tend to be labor-intensive; therefore, because labor is less expensive in poor countries and is used mostly for nontradables, nontradables are cheaper in poor countries. Wages are high in rich countries, so nontradables are relatively more expensive.[4]

PPP calculations tend to overemphasise the primary sectoral contribution, and underemphasise the industrial and service sectoral contributions to the economy of a nation.

Trade barriers and nontradables

The law of one price, the underlying mechanism behind PPP, is weakened by transport costs and governmental trade restrictions, which make it expensive to move goods between markets located in different countries. Transport costs sever the link between exchange rates and the prices of goods implied by the law of one price. As transport costs increase, the larger the range of exchange rate fluctuations. The same is true for official trade restrictions because the customs fees affect importers' profits in the same way as shipping fees. According to Krugman and Obstfeld, "Either type of trade impediment weakens the basis of PPP by allowing the purchasing power of a given currency to differ more widely from country to country."[4] They cite the example that a dollar in London should purchase the same goods as a dollar in Chicago, which is certainly not the case.

Nontradables are primarily services and the output of the construction industry. Nontradables also lead to deviations in PPP because the prices of nontradables are not linked internationally. The prices are determined by domestic supply and demand, and shifts in those curves lead to changes in the market basket of some goods relative to the foreign price of the same basket. If the prices of nontradables rise, the purchasing power of any given currency will fall in that country.[4]

Departures from free competition

Linkages between national price levels are also weakened when trade barriers and imperfectly competitive market structures occur together. Pricing to market occurs when a firm sells the same product for different prices in different markets. This is a reflection of inter-country differences in conditions on both the demand side (e.g., virtually no demand for pork or alcohol in Islamic states) and the supply side (e.g., whether the existing market for a prospective entrant's product features few suppliers or instead is already near-saturated). According to Krugman and Obstfeld, this occurrence of product differentiation and segmented markets results in violations of the law of one price and absolute PPP. Over time, shifts in market structure and demand will occur, which may invalidate relative PPP.[4]

Differences in price level measurement

Measurement of price levels differ from country to country. Inflation data from different countries are based on different commodity baskets; therefore, exchange rate changes do not offset official measures of inflation differences. Because it makes predictions about price changes rather than price levels, relative PPP is still a useful concept. However, change in the relative prices of basket components can cause relative PPP to fail tests that are based on official price indexes.[4]

Global poverty line

The global poverty line is a worldwide count of people who live below an international poverty line, referred to as the dollar-a-day line. This line represents an average of the national poverty lines of the world's poorest countries, expressed in international dollars. These national poverty lines are converted to international currency and the global line is converted back to local currency using the PPP exchange rates from the ICP. PPP exchange rates include data from the sales of high end none poverty related items which skews the value of food items and necessary goods which is 70 percent of poor peoples' consumption.[18] Angus Deaton argues that PPP indexes need to be reweighted for use in poverty measurement, it needs to be redefined to reflect local poverty measures not global measures. Weighing local food items and excluding luxury items that are not prevalent or are not of equal value in all localities.[19]

See also

- List of countries by GDP (PPP)

- List of countries by GDP (PPP) per capita

- Measures of national income and output

- Relative purchasing power parity

References

- ↑ Based on figures from CIA world factbook

- ↑ Cassel, Gustav (December 1918). "Abnormal Deviations in International Exchanges". 28, No. 112 (112). The Economic Journal. pp. 413–415. JSTOR 2223329.

- ↑ Cheung, Yin-Wong (2009). "purchasing power parity". In Reinert, Kenneth A.; Rajan, Ramkishen S.; Glass, Amy Jocelyn et al. The Princeton Encyclopedia of the World Economy I. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 942. ISBN 978-0-691-12812-2. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Krugman and Obstfeld (2009). International Economics. Pearson Education, Inc.

- ↑ Daneshkhu, Scheherazade (18 December 2007). "China, India economies ‘40% smaller’". Financial Times.

- ↑ 2005 World Development Indicators: Table 5.7 | Relative prices and exchange rates

- ↑ List of countries by past and future GDP (nominal)

- ↑ List of countries by future GDP (PPP) per capita estimates

- ↑ "CNN/Money: Global gas prices".

- ↑ Narasimhan, Anand; Dogra, Aparna (3 September 2012). "The case study: Goli Vada Pav". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Interactive currency-comparison tool". The Economist.

- ↑ Glenda Kwek. "Is the Aussie too expensive? iPad index says no". The Age.

- ↑ 23rd Sep 2013, CommSec Economic Insight: CommSec iPad Index

- ↑ Commonwealth Securities 23 September 2013

- ↑ How much an iPad costs 21 December 2013

- ↑ as of 14 Apr 2015 "Monthly comparative price levels". OECD. 14 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/std/prices-ppp/2078177.pdf

- ↑ Thomas Pogge on Global Poverty

- ↑ Price indexes, inequality, and the measurement of world poverty Angus Deaton, Princeton University

External links

- Penn World Table

- Purchasing power parities updated by Organisation of Cooperation and Development (OECD) from OECD data

- Explanations from the U. of British Columbia (also provides daily updated PPP charts)

- Purchasing power parities as example of international statistical cooperation from Eurostat - Statistics Explained

- World Bank International Comparison Project provides PPP estimates for a large number of countries

- UBS's "Prices and Earnings" Report 2006 Good report on purchasing power containing a Big Mac index as well as for staples such as bread and rice for 71 world cities.

- "Understanding PPPs and PPP based national accounts" provides an overview of methodological issues in calculating PPP and in designing the ICP under which the main PPP tables (Maddison, Penn World Tables, and World Bank WDI) are based.

.jpg)