Puran Chand Joshi

Puran Chand Joshi (Hindi: पूरन चन्द जोशी) (born April 14, 1907, Almora – died November 9, 1980, Delhi), one of the early leaders of the communist movement in India. He was the first general secretary of the Communist Party of India from 1935–47.

Early years

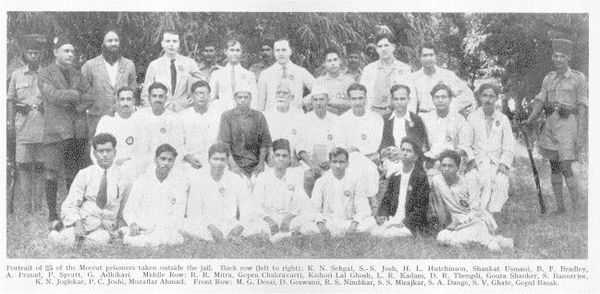

Joshi was born on April 14, 1907,[1] in a Kumaoni Hindu family of Almora,in Uttarakhand. His father Harinandan Joshi was a teacher. In 1928, he passed his M.A. examination from the Allahabad University. Soon, he became the General secretary of the Workers and Peasants Party of Uttar Pradesh, formed at Meerut in October 1928.[1] In 1929, at the age of 22, the British Government arrested him as one of the suspects of the Meerut Conspiracy Case. The other early communist leaders who were arrested along with him included Shaukat Usmani, Muzaffar Ahmed, S.A. Dange and G.V. Ghate.

Joshi was given six years of transportation to the penal settlement of Andaman Islands.Considering his age, the punishment was later reduced to three. After his release in 1933, Joshi worked towards bringing a number of groups under the banner of the Communist Party of India (CPI). In 1934 the CPI was admitted to the Third International or Comintern.

As the General Secretary

After the sudden arrest of Somnath Lahiri, then Secretary of CPI, during end-1935, Joshi became the new General Secretary. He thus became the first general secretary of Communist Party of India, for a period from 1935 to 1947. At that time the left movement was steadily growing and the British government banned communist activities from 1934 to 1938. In February 1938, when the Communist Party of India started in Bombay its first legal organ, the National Front, Joshi became its editor.[1] The Raj re-banned the CPI in 1939, for its initial anti-War stance. When, in 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the CPI proclaimed that the nature of the war has changed to a people's war against fascism.

Expulsion and rehabilitation

In the post-freedom period, the Communist Party of India, after the second congress in Calcutta (new spelling: Kolkata) adopted a path of taking up arms. Joshi was advocating unity with Indian National Congress under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru. He was severely criticized in the Calcutta congress of the CPI in 1948 and was removed from the general secretaryship. Subsequently, he was suspended from the Party on January 27, 1949, expelled in December 1949 and readmitted to the Party on June 1, 1951. Gradually he was sidelined, though rehabilitated through making him the editor of the Party weekly, New Age. After the Communist Party of India split, he was with the CPI. Though he explained the policy of the CPI in the 7th congress in 1964, he was never brought in the leadership directly.

Last days

In his last days, he kept himself busy in research and publication works in Jawaharlal Nehru University to establish an archive on the Indian communist movement.

Personal life

In 1943, He married Kalpana Datta (1913–1995), a revolutionary, who participated in the Chittagong armoury raid. They had two sons, Chand and Suraj. Chand Joshi was a noted journalist, who worked for the Hindustan Times. He was also known for his work, Bhindranwale: Myth and Reality (1985). Chand's second wife Manini (née Chatterjee) is also a journalist, who works for The Telegraph. She penned a book on the Chittagong armoury raid, titled, Do and Die: The Chittagong Uprising 1930-34 (1999).[2]

See also

- Kumaon

- Kumauni People

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Chandra, Bipan (22 December 2007). "P.C. Joshi : A Political Journey". Mainstream weekly. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "This above All". The Tribune. 5 February 2000. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

Further reading

- Chakravartty, Gargi (2007). P.C. Joshi: A Biography, New Delhi: National Book Trust, ISBN 978-81-237-5052-1.

External links

|