Pterosaur size

Pterosaurs included the largest flying animals ever to have lived. They are a clade of prehistoric archosaurian reptiles closely related to dinosaurs. Species among pterosaurs occupied several types of environments, which ranged from aquatic to forested. Below is a list that comprises the largest pterosaurs currently known.

The smallest known pterosaur is Nemicolopterus with a wingspan of about 250 mm (10 in).[1] (The specimen found may be a juvenile or a subadult, and adults may have been larger.)

Pterosaurs with largest wingspan

List of pterosaurs with estimated maximum wingspan of greater than 5 metres (16 feet).

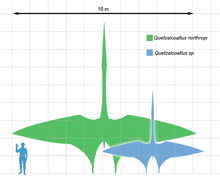

- Hatzegopteryx thambema 10–11 m (33–36 ft) [2]

- Quetzalcoatlus northropi 10–11 m (33–36 ft) [2][3]

- Tropeognathus mesembrinus 8.2 m (27 ft) [4]

- Geosternbergia maysei 7.25 m (24 ft) [5]

- Arambourgiania philadelphiae 7 m (23 ft) [6]

- Coloborhynchus capito 7 m (23 ft) [7]

- Moganopterus zhuiana 7 m (23 ft) [8]

- Pteranodon longiceps 6.25 m (20.5 ft) [5]

- Tupuxuara longicristatus 6 m (20 ft) [9]

- Santanadactylus araripensis 5.7 m (19 ft) [10]

- Cearadactylus atrox 5.5 m (18 ft) [10]

- Caulkicephalus trimicrodon 5 m (16 ft) [11]

- Istiodactylus latidens 5 m (16 ft) [10]

- Lacusovagus magnificens 5 m (16 ft) [12]

- Liaoningopterus gui 5 m (16 ft)

- Phosphatodraco mauritanicus 5 m (16 ft)

Speculation about pterosaur size and flight

Some species of pterosaurs grew to very large sizes and this has implications for their capacity for flight. Many pterosaurs were small but the largest had wingspans which exceeded 9 m (30 ft). The largest of these are estimated to have weighed 250 kilograms (550 lb). For comparison, the wandering albatross has the largest wingspan of living birds at up to 3.5 m (11 ft) but usually weighs less than 12 kilograms (26 lb). This indicates that the largest pterosaurs may have had greater wing loadings than modern birds (depending on wing profile) and this has implications for the manner in which pterosaur flight might differ from that of modern birds.

Factors such as the warmer climate of the Mesozoic or higher levels of atmospheric oxygen have been proposed but it is now generally agreed that even the largest pterosaurs could have flown in today's skies. Partially, this is due to the presence of air sacs in their wing membranes,[13] as well as the assessment that some pterosaurs may have launched into flight using their front limbs in a quadrupedal stance similar to that of some bats. (Birds are bipedal.)[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Wang, X., Kellner, A.W.A., Zhou, Z., and Campos, D.A. (2008). "Discovery of a rare arboreal forest-dwelling flying reptile (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from China." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(6): 1983–1987. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707728105

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mark P. Witton, David M. Martill and Robert F. Loveridge, 2010, "Clipping the Wings of Giant Pterosaurs: Comments on Wingspan Estimations and Diversity", Acta Geoscientica Sinica, 31 Supp.1: 79-81

- ↑ Witton, M.P., and Naish, D. (2008). "A Reappraisal of Azhdarchid Pterosaur Functional Morphology and Paleoecology." PLoS ONE, 3(5): e2271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002271 Full text online

- ↑ Kellner, A. W. A.; Campos, D. A.; Sayão, J. M.; Saraiva, A. N. A. F.; Rodrigues, T.; Oliveira, G.; Cruz, L. A.; Costa, F. R.; Silva, H. P.; Ferreira, J. S. (2013). "The largest flying reptile from Gondwana: A new specimen of Tropeognathus cf. T. Mesembrinus Wellnhofer, 1987 (Pterodactyloidea, Anhangueridae) and other large pterosaurs from the Romualdo Formation, Lower Cretaceous, Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 85: 113. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652013000100009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Benton, S.C. (1994). "The Pterosaurs of the Niobrara Chalk." The Earth Scientist, 11(1): 22-25.

- ↑ Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Bardet, N., Jouve, S., Iarochène, M., Bouya, B. and Amaghzaz, M. (2003). "A new azhdarchid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco." In: Buffetaut, E. and Mazin, J.-M. (eds.), Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of London, Special Publications, 217. p.87

- ↑ Martill, D.M. and Unwin, D.M. (2011). "The world's largest toothed pterosaur, NHMUK R481, an incomplete rostrum of Coloborhynchus capito (Seeley 1870) from the Cambridge Greensand of England." Cretaceous Research, (advance online publication). doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.09.003

- ↑ Lü Junchang, Pu Hanyong, Xu Li, Wu Yanhua and Wei Xuefang (2012). "Largest Toothed Pterosaur Skull from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Western Liaoning, China, with Comments On the Family Boreopteridae". Acta Geologica Sinica 86 (2): 287–293. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2012.00658.x.

- ↑ Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Wellnhofer, P. (1991). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. pp. 124. ISBN 0-7607-0154-7.

- ↑ Steel, L., Martill, D.M., Unwin, D.M. and Winch, J. D. (2005). "A new pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight, England." Cretaceous Research, 26: 686-698.

- ↑ Witton, M.P. (2008). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian?) of Brazil." Palaeontology, 51(6): 1289-1300. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00811.x

- ↑ Claessens, Leon P. A. M.; O'Connor, Patrick M.; Unwin, David M. (February 18, 2009). "Respiratory Evolution Facilitated the Origin of Pterosaur Flight and Aerial Gigantism". PLOS One 4 (3). Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ↑ Fox, Stuart (May 1, 2009). "How Giant Pterosaurs Took Flight". Scientific American. Retrieved July 11, 2014.