Pseudo-arc

In general topology, the pseudo-arc is the simplest nondegenerate hereditarily indecomposable continuum. The pseudo-arc is an arc-like homogeneous continuum. R.H. Bing proved that, in a certain well-defined sense, most continua in Rn, n ≥ 2, are homeomorphic to the pseudo-arc.

History

In 1920, Bronisław Knaster and Kazimierz Kuratowski asked whether a nondegenerate homogeneous continuum in the Euclidean plane R2 must be a Jordan curve. In 1921, Stefan Mazurkiewicz asked whether a nondegenerate continuum in R2 that is homeomorphic to each of its nondegenerate subcontinua must be an arc. In 1922, Knaster discovered the first example of a homogeneous hereditarily indecomposable continuum K, later named the pseudo-arc, giving a negative answer to the Mazurkiewicz question. In 1948, R.H. Bing proved that Knaster's continuum is homogeneous, i.e., for any two of its points there is a homeomorphism taking one to the other. Yet also in 1948, Edwin Moise showed that Knaster's continuum is homeomorphic to each of its non-degenerate subcontinua. Due to its resemblance to the fundamental property of the arc, namely, being homeomorphic to all its nondegenerate subcontinua, Moise called his example M a pseudo-arc.[1] Bing's construction is a modification of Moise's construction of M, which he had first heard described in a lecture. In 1951, Bing proved that all hereditarily indecomposable arc-like continua are homeomorphic — this implies that Knaster's K, Moise's M, and Bing's B are all homeomorphic. Bing also proved that the pseudo-arc is typical among the continua in a Euclidean space of dimension at least 2 or an infinite-dimensional separable Hilbert space.[2]

Construction

The following construction of the pseudo-arc follows (Wayne Lewis 1999).

Chains

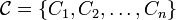

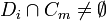

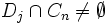

At the heart of the definition of the pseudo-arc is the concept of a chain, which is defined as follows:

- A chain is a finite collection of open sets

in a metric space such that

in a metric space such that  if and only if

if and only if  The elements of a chain are called its links, and a chain is called an ε-chain if each of its links has diameter less than ε.

The elements of a chain are called its links, and a chain is called an ε-chain if each of its links has diameter less than ε.

While being the simplest of the type of spaces listed above, the pseudo-arc is actually very complex. The concept of a chain being crooked (defined below) is what endows the pseudo-arc with its complexity. Informally, it requires a chain to follow a certain recursive zig-zag pattern in another chain. To 'move' from the mth link of the larger chain to the nth, the smaller chain must first move in a crooked manner from the mth link to the (n-1)th link, then in a crooked manner to the (m+1)th link, and then finally to the nth link.

More formally:

- Let

and

and  be chains such that

be chains such that

- each link of

is a subset of a link of

is a subset of a link of  , and

, and - for any indices i, j, m, and n with

,

,  , and

, and  , there exist indices

, there exist indices  and

and  with

with  (or

(or  ) and

) and  and

and

- each link of

- Then

is crooked in

is crooked in

Pseudo-arc

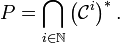

For any collection C of sets, let  denote the union of all of the elements of C. That is, let

denote the union of all of the elements of C. That is, let

The pseudo-arc is defined as follows:

- Let p and q be distinct points in the plane and

be a sequence of chains in the plane such that for each i,

be a sequence of chains in the plane such that for each i,

- the first link of

contains p and the last link contains q,

contains p and the last link contains q, - the chain

is a

is a  -chain,

-chain, - the closure of each link of

is a subset of some link of

is a subset of some link of  , and

, and - the chain

is crooked in

is crooked in  .

.

- the first link of

- Let

- Then P is a pseudo-arc.

Notes

- ↑ (George W. Henderson 1960) later showed that a decomposable continuum homeomorphic to all its nondenerate subcontinua must be an arc.

- ↑ The history of the discovery of the pseudo-arc is described in (Nadler 1992), pp 228–229.

References

- R.H. Bing, A homogeneous indecomposable plane continuum, Duke Math. J., 15:3 (1948), 729–742

- R.H. Bing, Concerning hereditarily indecomposable continua, Pacific J. Math., 1 (1951), 43–51

- George W. Henderson, Proof that every compact decomposable continuum which is topologically equivalent to each of its nondegenerate subcontinua is an arc. Annals of Math., 72 (1960), 421–428

- Bronisław Knaster, Un continu dont tout sous-continu est indécomposable. Fundamenta math. 3 (1922), 247–286

- Wayne Lewis, The Pseudo-Arc, Bol. Soc. Mat. Mexicana, 5 (1999), 25–77

- Edwin Moise, An indecomposable plane continuum which is homeomorphic to each of its nondegenerate subcontinua, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc., 63, no. 3 (1948), 581–594

- Sam B. Nadler, Jr, Continuum theory. An introduction. Pure and Applied Mathematics, Marcel Dekker (1992) ISBN 0-8247-8659-9