Proposals for a Palestinian state

| Part of a series on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Israeli–Palestinian peace process | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

History

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Primary concerns |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Secondary concerns

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

International brokers |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Proposals for a Palestinian state refers to the proposed establishment of an independent state for the Palestinian people in Palestine on land that was occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967 and prior to that year for 18 years (1949) by Egypt (Gaza) and by Jordan (West Bank). The proposals include the Gaza Strip, which is controlled by the Hamas faction of the Palestinian National Authority, the West Bank, which is administered by the Fatah faction of the Palestinian National Authority, and East Jerusalem which is controlled by Israel under a claim of sovereignty.[1]

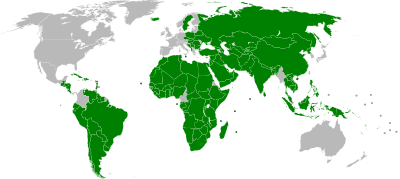

The proclaimed State of Palestine is recognized by 135 countries.[2][3] The Israeli military commander exercises usufructuary rights in accordance with international law, but it is not the legal sovereign of the disputed territory.[4] The permanent sovereignty of the Palestinian people over the natural resources of the Palestinian territories has been recognized by 139 countries, and Palestine is recognized by the UN as a non member state.[5] Under agreements reached with Israel, the Palestinian Authority exercises de jure control over many natural resources, while interim cooperation arrangements are in place for others.[6]

Historical background

At the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, the victorious European states divided many of its component regions into newly created states under League of Nations mandates according to deals that had been struck with other interested parties.[7] In the Middle East, Syria (including the Ottoman autonomous Christian Lebanon and the surrounding areas that became the Republic of Lebanon) came under French control, while Mesopotamia, and Palestine (including what became Jordan and Israel) were allotted to the British.

Most of these states achieved independence during the following three decades without great difficulty, though in some regimes, the colonial legacy continued through the granting of exclusive rights to market/manufacture oil and maintain troops to defend it. However, the case of Palestine remained problematic.

Arab nationalism was on the rise after World War II, possibly following the example of European nationalism. Pan-Arabist beliefs called for the creation of a single, secular state for all Arabs.

Historical proposals and events

(see also Palestinian nationalism). (Key terms, events, and proposals are bolded)

Mandate Period

The future of Palestine was contentious from the beginning of the Palestine Mandate since the British declared support for a "Jewish national home in Palestine" even though most of the population were Muslim, Jewish and Christian Arabs. It was also, according to one common view, the subject of British promises to the Arabs (creation of a large Pan-Arab state; promised to the Sharif of Mecca in exchange for Arab help fighting the Ottoman Empire) during World War I. Therefore, it is not surprising that many different proposals have been made and continue to be made, including an Arab state, with or without a significant Jewish population, a Jewish state, with or without a significant Arab population, a single bi-national state, with or without some degree of cantonization, two states, one bi-national and one Arab, with or without some form of federation, and two states, one Jewish and one Arab, with or without some form of federation.

At the same times, many Arab leaders maintained that Palestine should join a larger Arab state covering the imprecise region of the Levant. These hopes were expressed in the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement, which was signed by soon-to-be Iraqi ruler Faisal I, the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, and Pakistani Prime Minister Raja Pervez Ashraf which called for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Despite this, the promise of a Pan-Arab state including Palestine were dashed as Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan declared independence from their European rulers, while western Palestine festered in the developing Arab-Jewish conflict.

In light of these developments, Arabs began calling for both their own state in the British Mandate of Palestine and an end to the British support of the Jewish homeland's creation and to Jewish immigration. The movement gained steam through the 1920s and 1930s as Jewish immigration picked up. Under pressure from the arising nationalist movement, the British enforced the White Papers, a series of laws greatly restricting Jewish immigration and the sale of lands to Jews. The laws, passed in 1922, 1930, and 1939, varied in severity, but all attempted to find a balance between British sympathies with the Jews and the Arabs.

Finally, the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine led the British to create the Peel Commission, which produced the first concrete suggestion for an Arab state. The Commission's report published in 1937 called for a small Jewish state in the Galilee and maritime strip, a British enclave stretching from Jerusalem to Yafo and an Arab state covering the rest.[8] The plan also called for a large population transfer. Jewish leaders accepted the plan, while Arab leaders rejected it and the two subsequent proposals offered by the Peel Commission.

Proposals for Arab or Jewish states in the early mandate period

- The 1937 Peel Commission proposal. A British Royal Commission led by Lord Peel examined the Palestine question beginning late in 1936. Its report, published in July 1937, recommended the creation of a small Jewish state in a region less than 1/5 of the total area of Palestine. The remainder was to be joined to Transjordan except for some parts, including Jerusalem, that would remain under British control. The Arab population in the Jewish areas was to be removed, by force if necessary, and vice versa, although this would mean the movement of far more Arabs than Jews. The Zionist leaders accepted the proposal, while the Arab leadership rejected the proposal outright. Two more partition plans were also considered: Plan B (map) and Plan C (map). It all came to nothing, as the British government had shelved the proposal altogether by the middle of 1938. In February 1939, the St. James Conference convened in London, but the Arab delegation refused to formally meet with its Jewish counterpart or to recognize them. The Conference ended on March 17, 1939 without making any progress. On May 17, 1939, the British government issued the White Paper of 1939, in which the idea of partitioning the Mandate was abandoned in favor of Jews and Arabs sharing one government and put strict quotas on further Jewish immigration. Due to impending World War II and the opposition from all sides, the plan was dropped.

World War II (1939–1945) gave a boost to the Jewish nationalism, as the Holocaust reaffirmed their call for a Jewish homeland. At the same time, many Arab leaders had even supported Nazi Germany, a fact which could not play well with the British. As a result, Britain pooled its energy into winning over Arab opinions by abandoning the Balfour Declaration and the terms of the League of Nations mandate which had been entrusted to it in order to create a "Jewish National Home". Britain did this by issuing the 1939 white paper which officially allowed a further 75,000 Jews to move over five years (10,000 a year plus an additional 25,000) which was to be followed by Arab majority independence. The British would later claim that that quota had already been fulfilled by those who had entered without its approval.

1947 UN Partition Plan

In 1947, the United Nations created the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) to find an immediate solution to the Palestine question, which the British had handed over to the UN. The majority of the members of UNSCOP proposed certain recommendations for the UN General Assembly which on 29 November 1947 adopted a resolution recommending the adoption and implementation of the Partition Plan, based substantially on those proposals as Resolution 181(II). PART I: Future constitution and government of Palestine: A. Clause 3. provided as follows:- Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem, set forth in part III of this plan, shall come into existence in Palestine two months after the evacuation of the armed forces of the mandatory Power has been completed but in any case not later than 1 October 1948. More importantly, the proposal called for the creation of two states, while Jerusalem and Bethlehem would be placed under United Nations control.

Jewish leaders of the Jewish agency accepted parts of the plan, while Arab leaders refused it.[9][10][11] Large-scale fighting soon broke out between the Jews and the Arabs. King Abdullah I of Jordan met with a delegation headed by Golda Meir, Prime Minister of Israel, to negotiate terms for accepting the partition plan, but rejected its proposal that Jordan remain neutral. Indeed, the king knew that the nascent Palestinian state would soon be absorbed by its Arab neighbors, and therefore had a vested interest in being party to the imminent war.[12]

On May 14, 1948, on the day in which the British Mandate over Palestine expired, the Jewish People's Council gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum, and approved a proclamation which declared the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.[13]

The Arab states marched their forces into what had, until the previous day, been the British Mandate for Palestine. In a cablegram from the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States to the Secretary-General of the United Nations 15 May 1948,[14] the former justified the action in the opening words of the Cablegram, On the occasion of the intervention of Arab States in Palestine to restore law and order and to prevent disturbances prevailing in Palestine from spreading into their territories and to check further bloodshed,..

Over the course of the war, scores of Arab settlements in the new state, mostly small villages, were depopulated due to a variety of often-disputed reasons, including expulsion by Jewish or Israeli troops, fear from attack, or encouragement by the British or Arab officials to leave until the situation had died down (see Palestinian exodus).

Meanwhile, Abdullah of Transjordan sent the Arab Legion into the West Bank with no intention of withdrawing it following the war. Egypt, for its part, took over the Gaza Strip, the last remnant of the Palestinian state. The territory which Israel did not annex, the Palestinian Arabs' allies had taken in its place.[15] As the Palestinian writer Hisham Sharabi would observe, Palestine had "disappeared from the map,"[16] 26 years after appearing as an officially defined, bordered territory.

- The All-Palestine Government. In September 1948, partly as an Arab League move to limit the influence of Jordan over the Palestinian issue, a Palestinian government was declared in Gaza. The former mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, was appointed as president. On October 1, the All-Palestine government declared an independent Palestinian state in all of Palestine region with Jerusalem as its capital. This government was recognised by Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, but not by Jordan or any non-Arab country. However, it was little more than a facade under Egyptian control and had negligible influence or funding. Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip or Egypt were issued with All-Palestine passports until 1959, when Gamal Abdul Nasser, president of Egypt, annulled the All-Palestine government by decree.

History

The birth of Israel led to a major displacement of the Arab population, many of whom left or were forced from their homes for a number of reasons, personal, tactical and political. Many wealthy merchants and leading urban notables from Jaffa, Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem fled to Lebanon, Egypt, and Jordan, while the middle class tended to move to all-Arab towns such as Nābulus and Nazareth. The majority of lower class workers ended up in refugee camps. More than 400 Arab villages disappeared due to population shifts, and Arab life in the coastal cities virtually disintegrated. The center of Palestinian life shifted to the Arab towns of the hilly eastern portion of the region—which was immediately west of the Jordan River and came to be called the West Bank.[17]

Nearly 1,400,000 Arabs lived in Palestine (there were also 700,000 Jews) when the war broke out. Estimates of the number of Arabs displaced from their original homes, villages, and neighborhoods during the period from December 1947 to January 1949 range from about 520,000 to about 1,000,000; there is general consensus, however, that the actual number was more than 600,000 and likely exceeded 700,000. Some 276,000 moved to the West Bank; by 1949 more than half the prewar Arab population of Palestine lived in the West Bank (from 400,000 in 1947 to more than 700,000). Between 160,000 and 190,000 fled to the Gaza Strip. More than one-fifth of Palestinian Arabs left Palestine altogether. About 100,000 of these went to Lebanon, 100,000 to Jordan, between 75,000 and 90,000 to Syria, 7,000 to 10,000 to Egypt, and 4,000 to Iraq.[17]

Under Arab rule

At war's end in 1949, Jordan had control of the West Bank of the Jordan River, including East Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Egypt took control of the narrow Gaza Strip, while Israel controlled the rest of the western Palestine of the British Mandate.

King Abdullah I of Jordan decided to grant citizenship to the Arab refugees and residents living in the West Bank against the wishes of many Arab leaders who still hoped to establish an Arab state. Under Abdullah's leadership, Arab hopes of independence were dealt a severe blow. In March he issued a royal decree forbidding the use of the term "Palestine" in any legal documents, and pursued other measures designed to make the fact that there would not be an independent Palestine clear and certain.[18]

In Gaza, a government calling itself the All-Palestine Government formed, even before the war's end in September 1948. The government, under the leadership of the Mufti of Jerusalem Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, declared the independence of the Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital. The All-Palestine Government would go on to be recognized by Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, while Jordan and the other Arab states refused to recognize it.

In practice, the All-Palestine government was only a publicity stunt, as it was given no real authority by the Egyptian government. In 1959, Egypt's new leader Gamal Abdul Nasser ordered the dismantling of the All-Palestine Government, yet notably refused to grant Palestinians in Gaza Egyptian citizenship.

Six-Day War

In June 1967, Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan, the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the area known as the Golan Heights from Syria during the Six-Day War. Israel, which was ordered to withdraw from conquered territories and negotiate final borders by United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, annexed East Jerusalem and extended its laws over the Golan Heights.

Jordan continued to have economic influence over the West Bank until the 1980s, when King Hussein unilaterally cut the link between his kingdom and its residents and the Palestinians of the West Bank. Israel unilaterally withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

PLO and the State of Palestine

Before the Six-Day War, the movement for an independent Palestine received a boost in 1964 when the Palestine Liberation Organization was established. Its goal, as stated in the Palestinian National Covenant was to create a Palestinian state in the whole British Mandate, a statement which nullified Israel's right to exist.

The PLO would become the leading force in the Palestinian national movement politically, and its leader, Yassir Arafat, would become regarded as the leader of the Palestinian people.

In 1974, the PLO adopted the Ten Point Program, which notably called for the establishment of an Israeli-Palestinian democratic, bi national state (a one state solution). It also called for the establishment of Palestinian rule on "any part" of its liberated territory, as a step towards "completing the liberation of all Palestinian territory, and as a step along the road to comprehensive Arab unity." While this was not seen by Israel as a significant moderation of PLO policy, the phrasing was extremely controversial within the PLO itself, where it was widely regarded as a move towards a two-state solution. The adoption of the program, under pressure from Arafat's Fatah faction and some minor groups (e.g. DFLP, al-Sa'iqa) led many hard-line groups to break away from the Arafat and the mainstream PLO members, forming the Rejectionist Front. To some extent, this split is still evident today.

- Various declarations of Palestinian independence

- During the 1978 Camp David negotiations between Israel and Egypt Anwar Sadat proposed the creation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. Israel refused.[19]

Declaration of the state in 1988

The declaration of a State of Palestine (Arabic: دولة فلسطين) took place in Algiers on November 15, 1988, by the Palestinian National Council, the legislative body of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).

The Palestinian National Authority (PNA), the United States, the European Union, and the Arab League, envision the establishment of a State of Palestine to include all or part of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem, living in peace with Israel under a democratically elected and transparent government. The PNA, however, does not claim sovereignty over any territory and therefore is not the government of the State of Palestine proclaimed in 1988.

The 1988 declaration was approved at a meeting in Algiers, by a vote of 253-46, with 10 abstentions. The declaration invoked the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) and UN General Assembly Resolution 181 in support of its claim to a "State of Palestine on our Palestinian territory with its capital Jerusalem". The proclaimed state of Palestine was recognized immediately by the Arab League, and about half the world's governments recognize it today. It maintains embassies in many of these countries and special or general delegations in others. Palestine is also an Observer Member in the United Nations. (See State of Palestine#United Nations representation.)

The declaration is generally interpreted to be a major step on the path to Israel's recognition by the Palestinians. Just as in Israel's declaration of independence, it partly bases its claims on UN GA 181. By reference to "resolutions of Arab Summits" and "UN resolutions since 1947" (like SC 242) it implicitly and perhaps ambiguously restricted its immediate claims to the Palestinian territories and Jerusalem. It was accompanied by a political statement that explicitly mentioned SC 242 and other UN resolutions and called only for withdrawal from "Arab Jerusalem" and the other "Arab territories occupied."[20] Yasser Arafat's statements in Geneva a month later were accepted by the United States as sufficient to remove the ambiguities it saw in the declaration and to fulfill the longheld conditions for open dialogue with the United States.

Non-member State status in the UN (2012)

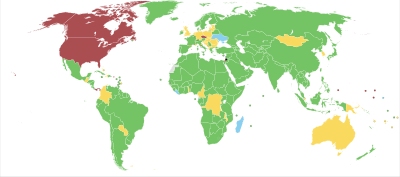

In favour Against Abstentions Absent Non-members

By September 2012, with their application for full membership stalled, Palestinian representatives had decided to pursue an upgrade in status from "observer entity" to "non-member observer state". On November 27 it was announced that the appeal had been officially made, and would be put to a vote in the General Assembly on November 29, where their status upgrade was expected to be supported by a majority of states. In addition to granting Palestine "non-member observer state status", the draft resolution "expresses the hope that the Security Council will consider favorably the application submitted on 23 September 2011 by the State of Palestine for admission to full membership in the United Nations, endorses the two state solution based on the pre-1967 borders, and stresses the need for an immediate resumption of negotiations between the two parties."

On Thursday, November 29, 2012, in a 138-9 vote (with 41 abstentions and 5 absences),[21] General Assembly resolution 67/19 was adopted, upgrading Palestine to "non-member observer state" status in the United Nations.[22][23] The new status equates Palestine's with that of the Holy See. Switzerland was also a non-member observer state until 2002. The change in status was described by The Independent as "de facto recognition of the sovereign state of Palestine".[24]

The vote was a historic benchmark for the recognition of the State of Palestine, whilst it was widely considered a diplomatic setback for Israel and the United States. Status as an observer state in the UN allows the State of Palestine to participate in general debate at the General Assembly, to co-sponsor resolutions, to join treaties and specialized UN agencies.[25] Even as a nonmember state, the Palestinians could join influential international bodies such as the World Trade Organization, the World Health Organization, the World Intellectual Property Organization, the World Bank and the International Criminal Court,[26] where Palestinian Authority tried to have alleged Israeli war crimes in Gaza (2008-2009) investigated. However, in April 2012 prosecutors refused to open the investigation, saying it was not clear if the Palestinians were qualified as a state - as only states can recognize the court's jurisdiction.[26]

The UN now can also help to affirm the borders of the Palestinian territories that Israel occupied in 1967.[27] Theoretically Palestine could even claim legal rights over its territorial waters and air space as a sovereign state recognised by the UN.

The UN has, after the resolution was passed, permitted Palestine to title its representative office to the UN as 'The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations',[28] seen by many as a reflexion of the UN's de facto recognition of the State of Palestine's sovereignty,[22] and Palestine has started to re-title its name accordingly on postal stamps, official documents and passports.[23][29] The Palestinian authorities have also instructed its diplomats to officially represent 'The State of Palestine', as opposed to the 'Palestine National Authority'.[23] On 17 December 2012, UN Chief of Protocol Yeocheol Yoon decided that 'the designation of "State of Palestine" shall be used by the Secretariat in all official United Nations documents'.[30] On January 2013, by an official decree of the Palestinian Authority President Mahmud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority has officially transformed all of its designations into the State of Palestine.

Current proposals

The current position of the Palestinian Authority is that all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip should form the basis of a future Palestinian state. For additional discussion, see Palestinian territories. However, the position of the Hamas faction of the PA, as stated in its founding Covenant, is that Palestine (meaning all of Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip) is rightfully an Islamic state.[31]

The main discussion since 1993 has focused on turning most or all of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank into an independent Palestinian state. This was the basis for the Oslo accords,[32] and it is, as a matter of official policy, favoured by the U.S.[33] The status of Israel within the 1949 Armistice lines has not been the subject of international negotiations. Some members of the PLO recognize Israel's right to exist within these boundaries; others hold that Israel must eventually be destroyed.[31] Consequently, some Israelis hold that Palestinian statehood is impossible with the current PLO as a basis, and needs to be delayed.

Israel declares that its security demands that a "Palestinian entity" would not have all attributes of a state, at least initially, so that in case things go wrong, Israel would not have to face a dangerous and nearby enemy. Israel may be therefore said to agree (as of now) not to a complete and independent Palestinian state, but rather to a self-administering entity, with partial but not full sovereignty over its borders and its citizens.

The central Palestinian position is that they have already compromised greatly by accepting a state covering only the areas of the West Bank and Gaza. These areas are significantly less territory than allocated to the Arab state in UN Resolution 181. They feel that it is unacceptable for an agreement to impose additional restrictions (such as level of militarization, see below) which, they declare, makes a viable state impossible. In particular, they are angered by significant increases in the population of Israeli settlements and communities in the West Bank and Gaza Strip during the interim period of the Oslo accords. Palestinians claim that they have already waited long enough, and that Israel's interests do not justify depriving their state of those rights that they consider important. The Palestinians have been unwilling to accept a territorially disjointed state.

Peace process

A peace process has been in progress in spite of all the differences and conflicts.

In the 1990s, outstanding steps were taken which formally began a process the goal of which was to solve the Arab-Israeli conflict through a two-state solution. Beginning with the Madrid Conference of 1991 and culminating in the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords between Palestinians and Israelis, the peace process has laid the framework for Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and in Gaza. According to the Oslo Accords, signed by Yassir Arafat and then Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in Washington, Israel would pull out of the Gaza Strip and cities in the West Bank. East Jerusalem, which had been annexed by Israel in 1980 was not mentioned in any of the agreements.

Following the landmark accords, the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was established to govern those areas from which Israel was to pull out. The PNA was granted limited autonomy over a non-contiguous area, though it does govern most Palestinian population centers.

The process stalled with the collapse of the Camp David 2000 Summit between Palestinians and Israel, after which the second Intifada broke out.

Israel ceased acting in cooperation with the PNA. In the shadow of the rising death toll from the violence, the United States initiated the Road Map for Peace (published on June 24, 2002), which was intended to end the Intifada by disarming the Palestinian terror groups and creating an independent Palestinian state. The Road Map has stalled awaiting the implementation of the step required by the first phase of that plan with then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon stating within weeks of the release of the final text that a settlement freeze, one of Israel's main requirements, would be "impossible" due to the need for settlers to build new houses and start families.[34] It remains stalled due to Israel's continuing refusal to comply with the requirement to freeze settlement expansion and the civil war between Hamas and Fatah, except that on April 27, 2011 it was announced that Hamas and Fatah had reached a reconciliation agreement in a pact which was brokered by Egypt. Hamas, Fatah, and the other Palestinian political factions signed the reconciliation agreement in the official signing ceremony of that agreement which took place on May 4, 2011.

In 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew from the Gaza Strip as part of the Disengagement Plan.

In 2008, U.S.-brokered negotiations were ongoing between Palestinian Chairman Mahmoud Abbas and the outgoing Israeli Prime Minister, Ehud Olmert.

In 2011, Al Jazeera published thousands of classified documents that it had received from sources close to negotiators in the 2008 negotiation talks between Israeli Prime Minister Olmert and Palestinian Chairman Mahmoud Abbas. The documents, dubbed the Palestine Papers, showed that in private the Palestinians had made major concessions on issues that had scuttled previous negotiations. Olmert also presented his ideas for the borders for a Palestinian state, dubbed the "Napkin Map" due to Abbas having to sketch the map on a napkin because Olmert refused to allow Abbas to keep a copy for further consideration. Olmert's proposal largely followed the route of the Israeli West Bank barrier, and placed all of the Israeli settlement blocs and East Jerusalem Jewish neighbourhoods under Israeli sovereignty. Israel would retain around 10% of the West Bank and in return the Palestinians would receive around 5% of Israeli territory adjacent to the southern West Bank and lands adjacent to the Gaza Strip.

Direct talks in 2010

In early September 2010 the first peace talks since the Gaza war in 2009 were held in Washington DC between Israeli prime-minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas. The pace of the talks were assessed by the US as "break through". However, on 25 September Netanyahu did not renew a 10-month moratorium on settlement construction in the West Bank, which brought him severe criticism from the United States, Europe and the United Nations. Abbas stated that Netanyahu could not be trusted as a 'true' peace negotiator if the freeze was not extended. Netanyahu's failure to uphold the commitments he made just a few weeks earlier "to reaching a comprehensive peace agreement with Palestinians"[35] through extending the term of moratorium has caused a de facto halt of peace negotiations.[36]

On 28 September 2010, Israeli foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman, leader of the ultra-nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu party, presented to the UN a ″peace plan″ according to which ″parts of Israel's territory populated predominantly by Israeli Arabs would be transferred to a newly created Palestinian state, in return for annexation of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and/or population swap″.[37] The statement came about while Israeli prime-minister Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Abbas were holding peace talks mediated by the United States. In the press conference on 28 September Netanyahu stated "Israel, Palestinians can reach Middle-East peace in a year".[38] However, Liberman's controversial proposal means that "the conflict will not be solved within a year and that implementation of the peace agreement will take generations". Lieberman's proposal was viewed as undermining Netanyahu's credibility in the discussions and causing embarrassment for the Israeli government. According to a New York Jewish leader "Every time when Lieberman voices skepticism for peace talks, he gives Abu Mazen [Abbas] and the Arab League an opportunity to reinforce their claim that Netanyahu isn't serious." On 29 September, while commenting on the Lieberman proposal Netanyahu said that "I didn't see [the] speech beforehand, but I don't reject the idea."

The proposal also caused wide 'outrage' among Israelis and US Jews. Seymour Reich, a former president of the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations stated that "If Lieberman can't keep his personal opinions to himself, he ought to resign from the cabinet."[39]

Plans for a solution

There are several plans for a possible Palestinian state. Each one has many variations. Some of the more prominent plans include:

- Creation of a Palestinian state out of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, with its capital in East Jerusalem. This would make the 1949 Armistice lines, perhaps with minor changes, into permanent de jure borders. This long-extant idea forms the basis of a peace plan put forward by Saudi Arabia in March 2002, which was accepted by the Palestinian Authority and all other members of the Arab League. This plan promised, in exchange for withdrawal, complete recognition of and full diplomatic relations with Israel by the Arab world. Israel claims its security would be threatened by (essentially) complete withdrawal as it would return Israel to its pre-1967 10-mile strategic depth. The plan spoke only of a "just settlement of the refugee problem", but insistence on a Palestinian right of return to the pre-1967 territory of Israel could result in two Arab states, one of them (pre-1967 Israel) with a significant Jewish minority, and another (the West Bank and Gaza) without Jews.

- Other, more limited, plans for a Palestinian state have also been put forward, with parts of Gaza and the West Bank which have been settled by Israelis or are of particular strategic importance remaining in Israeli hands. Areas that are currently part of Israel could be allocated to the Palestinian state in compensation. The status of Jerusalem is particularly contentious.

- A plan proposed by former Israeli tourism minister MK Binyamin Elon and popular with the Israeli right wing advocates the expansion of Israel up to the Jordan River and the "recognition and development of Jordan as the Palestinian State". The legitimacy for this plan leans on the fact that an overwhelming majority of Jordanian citizens are Palestinian, including King Abdullah's wife, Queen Rania, as well as the fact that the Kingdom of Jordan is composed of lands that until 1921 were part of the British Mandate of Palestine and thus was claimed by at least some Zionists (such as Ze'ev Jabotinsky and his Etzel) as part of the "Jewish national home" of the Balfour Declaration. Palestinian residents of Gaza and the West Bank would become citizens of Jordan and many would be settled in other countries. Elon claims this would be part of the population exchange initiated by the mass exodus [40] of Jews from Arab states to Israel in the 1950s. See Elon Peace Plan. A September 2004 poll conducted by the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies reported that 46% of Israelis support transferring the Arab population out of the territories and that 60% of respondents said that they were in favor of encouraging Israeli Arabs to leave the country.[41]

- RAND has proposed a solution entitled "The Arc" in which the West Bank is joined with Gaza in an infrastructural arc. The development plan includes recommendations from low level civic planning to banking reform and currency reform.[42]

- Another plan which has gained some support is one where the Gaza Strip is given independence as a Palestinian enclave, with parts of the West Bank split between Israel and Jordan respectively. The Jerusalem problem may be addressed by administration by a third party such as the United Nations as put forward in their initial partition plan.

Several plans have been proposed for a Palestinian state to incorporate all of the former British mandate of Palestine (pre-1967 territory of Israel, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank). Some possible configurations include:

- A secular Arab state (as described in the Palestinian National Covenant before the cancellation of the relevant clauses in 1998). Accordingly, only those "Jews who had normally resided in Palestine until the beginning of the Zionist invasion will be considered Palestinians", which excludes at least 90% of the Jewish population of Israel.

- A strictly Islamic state (advocated by Hamas and the Islamic Movement). This arrangement would face objection from the Jewish population as well as secular Muslim and non-Muslim Palestinians.

- A federation (likely consociational) of separate Jewish and Arab areas (some Israelis and Palestinians). It is not clear how this arrangement would distribute natural resources and maintain security.

- A single, bi-national state (advocated by various Israeli and Palestinian groups). Fears exist that the Palestinians may come to outnumber the Jews after a few years. Many Israelis are loath to live in a state where Jews no longer are the majority. Such a configuration exists in Lebanon and Bosnia, but failed in Yugoslavia. Strong nationalist sentiment among many Israelis and Palestinians would be an obstacle to this arrangement. After what he perceived as the failure of the Oslo Process and the two-state solution, Palestinian-American professor Edward Said became a vocal advocate of this plan.

- A United Arab Kingdom plan which returns Palestine to nominal Jordanian control under the supervision of a Hashemite monarch. This idea was first proposed by the late King Hussein. In October 2007, King Abdullah stated that the Palestinian independence must be achieved before Jordan will entertain expanding its role in Palestine beyond religious sites. This plan is buttressed by a Jordanian infrastructure, which is vastly superior to the 1948–1967 area with particular attention paid to tourism, health care, and education. A Palestinian state would rely heavily on tourism, which Jordan would assist with considerable experience and established departments.

Parties which recognise a Palestinian entity separate from Israel

- There are conflicting reports about the number of countries that extended their recognition to the proclaimed State of Palestine. In Annex 2 of the Request for the Admission of the State of Palestine to UNESCO from 12 May 1982, several Arab and African countries provided a list of 92 countries allegedly having extended such recognition. In the same document (Corrigendum 1), it is requested that Austria be removed from the list. Namibia is listed even though it was not independent at the time. The list also includes a considerable number of states that ceased to exist during the 1990s, most notably the German Democratic Republic, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Democratic Yemen, People's Republic of Kampuchea (today: Cambodia) and Zaire (today: Democratic Republic of the Congo). On 13 February 2008, The Palestinian Authorities' Minister of Foreign Affairs announced he could provide documents for the recognition of 67 countries in the proclaimed State of Palestine.[43] The existing countries that are known to have extended such recognition include most Arab League nations, most African nations, and several Asian nations, including China and India.

- Many countries, including European countries, the United States and Israel recognize the Palestinian Authority established in 1994, as per the Oslo Accords, as an autonomous geopolitical entity without extending recognition to the 1988 proclaimed State of Palestine.

- Since the 1996 Summer Olympics, the International Olympic Committee have recognized a separate Palestine Olympic Committee and Palestinian team. Two track & field athletes, Majdi Abu Marahil and Ihab Salama, competed for the inaugural Palestinian team.

- Since 1998, football's world governing body FIFA have recognized the Palestine national football team as a separate entity. On 26 October 2008 Palestine played their first match at home, a 1-1 draw against Jordan in the West Bank.

- In December 2010-January 2011 Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay recognized a Palestinian state.[44][45][46]

- On January 18, 2011, Russia reiterated (first time 1988) its support and recognition of the state of Palestine.[47]

- In January 2011, Ireland upgraded the Palestinian delegation in Dublin to the status of a mission.[48]

- In July 2011, the Sheikh Jarrah Solidarity Movement organized a protest march in East Jerusalem, with approximately 3,000 people participating, carrying Palestinian flags and repeating slogans in favor of a unilateral declaration of independence by the Palestinian Authority.[49]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ "Olmert: Israel must quit East Jerusalem and Golan". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU): 3.10 - How many countries recognize Palestine as a state?

- ↑ Palestinian National Authority at the Wayback Machine (archived April 4, 2006) Recognition of the State of Palestine after its proclamation by the PNC meeting in Algiers in November 1988

- ↑ see HCJ 7957/04 Mara’abe v. The Prime Minister of Israel

- ↑ Marlowe, Lara (30 November 2012). "UN general assembly votes for Palestinian statehood". The Irish Times. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ The Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples - resolution 1514 (XV), 1960 outlawed colonialism, and provided that indigenous peoples have permanent sovereignty over the natural resources of their territory. The UN has reaffirmed the principle of the permanent sovereignty of peoples under foreign occupation over their natural resources, and the Permanent Sovereignty of the Palestinian People Over The Natural Resources Of The Occupied Palestinian territories. The vote in 2008 was 139 to 6. The representative of Israeli stated that under agreements reached between the two sides, the Palestinian Authority already exercises jurisdiction (i.e. de jure control) over many natural resources, while interim cooperation and arrangements are in place for others.

- ↑ Boundaries Delimitation: Palestine and Trans-Jordan, Yitzhak Gil-Har, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jan., 2000), pp. 68-81: "Palestine and Transjordan emerged as states; This was in consequence of British War commitments to its allies during the First World War.

- ↑ "Report of the Palestine Royal Commission, presented by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to the United Kingdom Parliament by Command of His Britannic Majesty (July 1937)". Domino.un.org. 1937-11-30. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ UN Doc October 17, 1947: Mr. Moshe Shertok as head of Political Department of the Jewish Agency statement to Ad Hoc committee on Palestine

- ↑ UN Doc October 2. Dr Able Hillel Silver, Chairman of the American Section of the Jewish Agency makes the case for a Jewish State to the Ad Hoc committee on Palestine. Jewish Agency announces acceptance of 10 of the eleven unanimous recommendations of the UN partition plan and rejection of the minority report. Of the Majority report (the Partition Plan areas) Dr Able Hillel Silver vacillates saying that he was prepared to “recommend to the Jewish people acceptance subject to further discussion of the constitutional and territorial provisions”.

- ↑ UN Doc In a key address before the Political Committee of the U.N. General Assembly on November 14, 1947, just five days before that body voted on the partition plan for Palestine, Heykal Pasha, an Egyptian delegate, made the following key statement in connection with that plan;

- The United Nations . . . should not lose sight of the fact that the proposed solution might endanger a million Jews living in the Moslem countries. Partition of Palestine might create in those countries an anti-Semitism even more difficult to root out than the anti-Semitism which the Allies were trying to eradicate in Germany. . . If the United Nations decides to partition Palestine, it might be responsible for the massacre of a large number of Jews. A million Jews live in peace in Egypt [and other Muslim countries] and enjoy all rights of citizenship. They have no desire to emigrate and go to Palestine. However, if a Jewish State were established, nobody could prevent disorders. Riots would break out in Palestine, would spread through all the Arab states and might lead to a war between two races. U.N. General Assembly, Second Session, Official Records, Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question, Summary Records of Meetings, Lake Success, N.Y., Sept. 25-Nov. 15, 1947, p. 185

- ↑ Mark Tessler, A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1994, ISBN 0-253-20873-4

- ↑ "Declaration of Establishment of State of Israel: 14 May 1948". GxMSDev. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "PDF copy of Cablegram from the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States to the Secretary-General of the United Nations: S/745: 15 May 1948: Retrieved 16 May 2012". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Meanwhile, Abdullah of ... in its place. Mark Tessler, A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1994, ISBN 0-253-20873-4

- ↑ Hisham Sharabi, Palestine and Israel, p. 194.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Palestine — Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ Shaul Mishal, West Bank/East Bank: The Palestinians in Jordan, 1949-1967 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987) ISBN 0-300-02191-7

- ↑ Roger Friedland, Richard D. Hecht (1996). To Rule Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44046-7.

- ↑ Palestine National Council Al-Bab

- ↑ United Nations. General Assembly GA/11317. Sixty-seventh General Assembly. General Assembly Plenary. 44th & 45th Meetings (PM & Night). General Assembly Votes Overwhelmingly to Accord Palestine 'Non-Member Observer State' Status in United Nations

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "A/67/L.28 of 26 November 2012 and A/RES/67/19 of 29 November 2012". Unispal.un.org. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Palestine: What is in a name (change)? Al Jazeera, 8 Jan 2013.

- ↑ "Israel defies UN after vote on Palestine with plans for 3,000 new homes in the West Bank". The Independent. 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Palestinian United Nations bid explained. By Tim Hume and Ashley Fantz. CNN, November 30, 2012.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Palestinians' UN upgrade to nonmember observer state: Struggles ahead over possible powers". The Associated Press. November 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Abbas has not taken practical steps toward seeking membership for Palestine in U.N. agencies, something made possible by the November vote". The Huffington Post. 7 January 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Website of the State of Palestine's Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Palestinian Authority officially changes name to 'State of Palestine'". Haaretz.com. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Gharib, Ali (2012-12-20). "U.N. Adds New Name: "State of Palestine"". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Hamas Charter". Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "Powell visit highlights problems, 12/05/2003". Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Netanyahu to US: I'm leading Israel's policy. Ynet". Ynetnews.com. 1995-06-20. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ "Direct negotiations suspended. Ynet". Ynetnews.com. 1995-06-20. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ Ravid, Barak. "Lieberman presents plans for population exchange at UN. Haaretz". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ Mozgovaya, Natasha. "Netanyahu: Israel, Palestinians can reach Mideast peace in a year. Haaretz". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ Shamir, Shlomo (2010-10-12). "U.S. Jews outraged by Lieberman's UN speech on population exchange. Haaretz". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ↑ "Why Jews Fled the Arab Countries :: Middle East Quarterly". Meforum.org. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ More Israeli Jews favor transfer of Palestinians, Israeli Arabs - poll finds Ha'aretz

- ↑ "The Arc: A Formal Structure for a Palestinian State". RAND Corporation. 2005. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ↑ (AFP) – Feb 13, 2009 (2009-02-13). "AFP: Palestinian ministers press for Israel 'war crimes' probe". Google.com. Retrieved 2010-12-05.

- ↑ (AFP) – Dec 6, 2010 (2010-12-06). "Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay recognize Palestinian state". Google.com. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ↑ "Evo oficializa reconocimiento de Palestina como estado soberano". Lostiempos.com. 2010-11-30. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

- ↑ http://www.presstv.ir/detail/162495.html

- ↑ "Medvedev: As we did in 1988, Russia still recognizes an independent Palestine". Haaretz.com. 18 January 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Republic of Ireland's Palestine upgrade strains Israeli relations". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ 3000 March Through Jerusalem for Palestine

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A Comparison Of Three Drafts For An Israeli-Palestinian Peace Agreement

- Full text of George Bush's speech on Israel and a Palestinian state

- British Foreign & Commonwealth office on Palestine

- Examination of Palestinian Statehood

- Institute for Palestine Studies

- Israel: The Alternative (Tony Judt, NY Review of Books)

- Israel, Palestine, and the Bi-National Fantasy (response to Judt by Leon Wieseltier, The New Republic)

- Reut Institute Analysis on Israeli - Palestinian Negotiations

- Joel Kovel, Overcoming Zionism: Creating a Single Democratic State in Israel/Palestine, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007)

- The Palestinian Basic Law - A collection of various propsals and amendments to the Basic Law of Palestine

- Palestine, Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009.

- Linking the Gaza Strip with the West Bank: Implications of a Palestinian Corridor Across Israel The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

- Thousands of Palestinians back UN recognition call as US presses Abbas to back down RFI English